- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

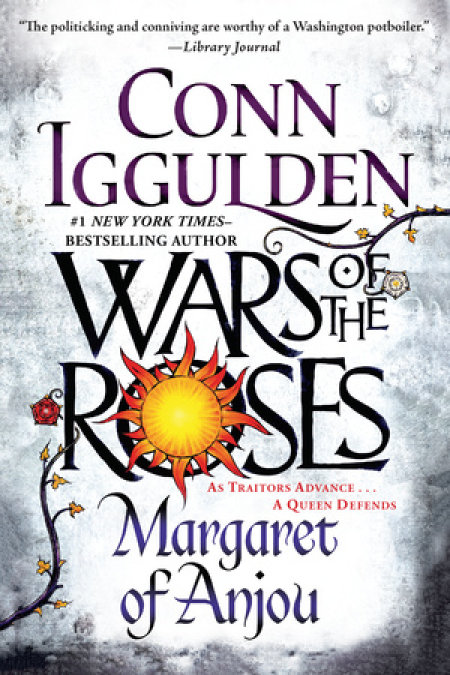

The brilliant retelling of the Wars of the Roses continues with Margaret of Anjou, the second gripping novel in the new series from historical fiction master Conn Iggulden.

As traitors advance . . . a queen defends.

It is 1454 and for more than a year King Henry VI has remained all but exiled in Windsor Castle, struck down by his illness, his eyes vacant, his mind blank. His fiercely loyal wife and queen, Margaret of Anjou, safeguards her husband’s interests, hoping that her son Edward will one day come to know his father.

With each month that Henry is all but absent as king, Richard, the duke of York, protector of the realm, extends his influence throughout the kingdom. A trinity of nobles--York and Salisbury and Warwick--are a formidable trio and together they seek to break the support of those who would raise their colors and their armies in the name of Henry and his queen.

But when the king unexpectedly recovers his senses and returns to London to reclaim his throne, the balance of power is once again thrown into turmoil. The clash of the Houses of Lancaster and York may be the beginning of a war that could tear England apart . . .

Following Stormbird, Margaret of Anjou is the second epic installment in master storyteller Conn Iggulden’s new Wars of the Roses series. Fans of the Game of Thrones and the Tudors series will be gripped from the word “go.”

Release date: June 16, 2015

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Wars of the Roses: Margaret of Anjou

Conn Iggulden

Part One

LATE SUMMER 1454

People crushed by law have no hopes but from power. If laws are their enemies, they will be enemies to laws.

-Edmund Burke

Chapter 1

With the light still cold and gray, the castle came alive. Horses were brought from their stalls and rubbed down; dogs barked and fought with each other, kicked out of the way by those who found them in their path. Hundreds of young men were busy gathering tack and weapons, rushing around the main yard with armfuls of equipment.

In the great tower, Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, stared out of the window to the bustling sward all around his fortress. The castle stones were warm in the August heat, but the old man wore a cloak and mantle of fur around his shoulders even so, clutched tight to his chest. He was still both tall and broad, though age had bowed him down. His sixth decade had brought aches and creaking joints that made all movement painful and his temper short.

The earl glowered through the leaded glass. The town was waking. The world was rising with the sun and he was ready to act, after so long biding his time. He watched as armored knights assembled, their servants passing out shields that had been painted black, or covered in sackcloth bound with twine. The Percy colors of blue and yellow were nowhere in evidence, hidden from view so that the soldiers waiting for his order had a somber look. For a time, they would be gray men, hedge knights without house or family. Men without honor, when honor was a chain to bind them.

The old man sniffed, rubbing hard at his nose. The ruse would fool no one, but when the killing was over, he would still be able to claim no Percy knight or archer had been part of it. Most importantly of all, those who might have cried out against him would be cold in the ground.

As he stood there, deep in thought, he heard his son approach, the young man’s spurred heels clicking and rattling on the wooden floor. The earl looked around, feeling his old heart thump with anticipation.

“God give you good day,” Thomas Percy said, bowing. He too allowed his gaze to stray through the window, down to the bustle of the castle grounds below. Thomas raised an eyebrow in silent question and his father grunted, irritated at the footsteps of servants all around.

“Come with me.” Without waiting for a reply, the earl swept along the corridor, the force of his authority pulling Thomas along behind him. He reached a doorway to his private chambers and almost dragged his son inside, slamming the door behind them. As Thomas stood and watched, the old man strode jerkily through the rooms, banging doors back and forth as he went. His suspicion showed in the deepening purple of his face, the skin made darker still by a stain of broken veins that stretched right across his cheeks and nose. The earl could never be pale, with that marbling. If it had been earned in strong spirits from over the Scottish border, it suited his mood well enough. Age had not mellowed the old man, though it had dried and hardened him.

Satisfied they were alone, the earl came back to his son, still waiting patiently with his back to the door. Thomas Percy, Baron Egremont, stood no taller than his father once had, though without the stoop of age he could see over the old man’s head. At thirty-two, Thomas was in the prime of his manhood, his hair black and his forearms thick with sinew and muscle earned over six thousand days of training. As he stood there, he seemed almost to glow with health and strength, his ruddy skin unmarked by scar or disease. Despite the years between them, both men bore the Percy nose, that great wedge that could be seen in dozens of crofts and villages all around Alnwick.

“There, we are private,” the earl said at last. “She has her ears everywhere, your mother. I cannot even talk to my own son without her people reporting every word.”

“What news, then?” his son replied. “I saw the men, gathering swords and bows. Is it the border?”

“Not today. Those damned Scots are quiet, though I don’t doubt the Douglas is forever sniffing round my lands. They’ll come in winter when they starve, to try and steal my cows. And we’ll send them running when they do.”

His son hid his impatience, knowing well that his father could rant about the “cunning Douglas” for an hour if he was given the chance.

“The men though, father. They have covered the colors. Who threatens us who must be taken by hedge knights?”

His father stood close to him, reaching out and hooking a bony hand over the lip of the leather breastplate to draw him in.

“Your mother’s Nevilles, boy, always and forever the Nevilles. Wherever I turn in my distress, there they are, in my path!” Earl Percy raised his other hand as he spoke, holding it up with the fingers joined like a beak. He jabbed the air with it, close by his son’s face. “Standing in such numbers they can never be counted. Married into every noble line! Into every house! I have the damned Scots clawing away at my flank, raiding England, burning villages in my own land. If I did not stand against them, if I let but one season pass without killing the young men they send to test me, they would come south like a dam bursting. Where would England be then, without Percy arms to serve her? But the Nevilles care nothing for all that. No, they throw their weight and wealth to York, that pup. He rises, held aloft by Neville hands, while titles and estates of ours are stolen away.”

“Warden of the West March,” his son muttered wearily. He had heard his father’s complaints many times before.

Earl Percy’s glare intensified.

“One of many. A title that should have been your brother’s, with fifteen hundred pounds a year, until that Neville, Salisbury, was given it. I have swallowed that, boy. I have swallowed him being made chancellor while my king dreams and sleeps and France was lost. I have swallowed so much from them that I find I am stuffed full.”

The old man had drawn his son so close their faces almost touched. He kissed Thomas brief ly on the cheek, letting him go. From long habit, he checked the room around them once more, though they were alone.

“You have good Percy blood in you, Thomas. It will drive your mother’s out in time, as I will drive out the Nevilles upon the land. They have been given to me, Thomas, do you understand? By the grace of God, I have been handed a chance to take back all they have stolen. If I were twenty years younger, I would take Windstrike and ride them down myself, but . . . those days are behind.” The old man’s eyes were almost feverish as he stared up at his son. “You must be my right arm in this, Thomas. You must be my sword and flail.”

“You honor me,” Thomas murmured, his voice breaking. As a mere second son, he had grown to his prime with little of the old man’s affection. His elder brother, Henry, was away with a thousand men across the border of Scotland, there to raid and burn and weaken the savage clans. Thomas thought of him and knew Henry’s absence was the true reason his father had taken him aside. There was no one else to send. Though the knowledge made him bitter, he could not resist the chance to show his worth to the one man he allowed to judge him.

“Henry has the best of our fighting cocks,” his father said, echoing his thoughts. “And I must keep some strong hands at Alnwick, in case the cunning Douglas slips your brother and comes south to rape and steal. That little man knows no greater pleasure than in taking what is mine. I swear he—”

“Father, I will not fail,” Thomas said. “How many will you send with me?”

His father paused in irritation at being interrupted, his eyes sharp with rebuke. At last, he nodded, letting it go.

“Seven hundred, or thereabouts. Two hundred men-at-arms, though the rest are brickmakers and smiths and common men with bows. You will have Trunning and if you have wit, you will let him advise you—and listen well to him. He knows the land around York and he knows the men. Perhaps if you had not spent so much of your youth on drink and whores, I would not doubt you. Whisht! Don’t take it hard, boy. There must be a son of mine in this, to give the men heart. But they are my men, not yours. Follow Trunning. He will not lead you wrong.”

Thomas flushed, his own anger rising. The thought of the two old men planning out some scheme together brought a tension to his frame that his father noted.

“You understand?” Earl Percy snapped. “Heed Trunning. That is my order to you.”

“I understand,” Thomas said, striving hard to conceal his disappointment. For one moment, he’d thought his father might trust him in command, rather than raising his brother, or some other man, over him. He felt the loss of something he’d never had.

“Will you tell me then where I must ride for you, or should I ask Trunning for that as well?” Thomas said.

His voice was strained, and his father’s mouth quirked in response, amused and scornful.

“I said not to take it hard, boy. You’ve a good right arm and you are my son, but you’ve not led, not beyond a few skirmishes. The men do not respect you, as they do Trunning. How could they? He’s fought for twenty years, in France and England both. He’ll see you safe.”

The earl waited for some sign that his son had accepted the point, but Thomas glowered, wounded and angry. Earl Percy shook his head, going on.

“There is a Neville marriage tomorrow, Thomas, down at Tattershall. Your mother’s clan has reached out to bring yet another into their grasp. That preening cockerel, Salisbury, will be there, to see his son wed. They will be at peace, content to take a new bride back to their holding at the manor of Sheriff Hutton. My man told me all, risking his bones to reach me in time. I paid him well for it, mind. Now listen. They will be on horses and on foot, a merry wedding party traipsing back to feast on a fine summer day. And you will be there, Thomas. You will ride them down, leaving no one alive. That is my order to you. Do you understand it?”

Thomas swallowed hard as his father watched him. Earl Salisbury was his mother’s brother, the man’s sons his own cousins. Thomas had been thinking he would ride out after some weaker branch of the Neville tree, not the root itself and the head of the clan. If he did as he was told, he would make more blood-enemies in a day than in his entire life to that point. Even so, he nodded, unable to trust his voice. His father’s mouth twisted sourly, seeing once again his son’s weakness and indecision.

“Salisbury’s boy is marrying Maud Cromwell. You know her uncle holds Percy manors, refusing my claim to them. It seems he thinks he can give my estates in dowry to the Nevilles, that they are now so strong I will be forced to drop my suits and cases against him. I am sending you to show them justice. To show them the authority Cromwell f louts as he seeks a greater shadow to hide beneath! Listen to me now. Take my seven hundred and kill them all, Thomas. Be sure Cromwell’s niece is among the dead, that I may invoke her name when next I meet her weeping uncle in the king’s court. Do you understand?”

“Of course I understand!” Thomas said, his voice hardening. He felt his hands tremble as he glared at his father, but he would not suffer the old man’s scorn by refusing. He set his jaw, the decision made.

A knock sounded on the door at Thomas’s back, making both men start like guilty conspirators. Thomas stood away to let it swing open, blanching at the sight of his mother standing there.

His father drew himself up, his chest puffing out.

“Go now, Thomas. Bring honor to your family and your name.” “Stay, Thomas,” his mother said quickly, her expression cold. Thomas hesitated, then dipped his head, slipping past her and

striding away. Alone, Countess Eleanor Percy turned sharply to her husband.

“I see your guards and soldiers arming themselves, covering Percy colors. Now my son rushes from me like a whipped cur. Will you have me ask, then? What foul plan have you been whispering into his ears this time, Henry? What have you done?”

Earl Percy took a deep breath, his triumph showing clearly.

“Were you not listening at the door like a maid, then? I am surprised,” he said. “What I havedone is no business of yours.” As he spoke, he moved to go past her into the corridor outside. Eleanor stepped into his path to stop him, raising her hand against his chest.

In response, the earl gripped it cruelly, crushing her fingers so that she cried out. He twisted further, controlling her with a hand on her elbow.

“Please, Henry. My arm . . .” she said, gasping.

He twisted harder at that, making her shriek. In the corridor, he caught a glimpse of a servant hurrying closer and kicked savagely at the door so that it slammed shut. As his wife whimpered, the old man bent her forward, almost doubled over, with his grip tight on her hand and arm.

“I have done no more than your Nevilles would do to me, if I were ever at their mercy,” he said into her ear. “Did you think I would allow your brother to rise above the Percy name? Chancellor to the Duke of York now, he threatens everything I am, everything I must protect. Do you understand? I took you on to give me sons, a fertile Neville bride. Well, you have done that. Now do not dare ask me the business of my house.”

“You are hurting me,” she said, her face crumpling in anger and pain. “You see enemies where there are none. And if you seek my brother, he will see you dead, Henry. Richard will kill you.”

With a grunt of outrage, her husband heaved her across the room, sending her sprawling across the bed. He was on her before she could rise to her feet, tearing her dress and bawling at her in red-faced rage as he wrenched at the cloth and bared her skin. She sobbed and struggled, but he was infernally strong in his anger, ignoring her nails as she left red lines on his face and arms. He held her down with one hand, exposing the long pale line of her back as he drew his belt from his trousers and doubled it over into a short whip.

“You will not speak to me in such a way, in my own house.” He landed blow after blow with the snapping sounds as loud as her desperate cries. No one came, though he went on and on until she was still, no longer struggling. Long red welts seeped blood to stain the fine cloth as he gasped and panted, fat beads of sweat dropping from his nose and brow onto her skin. With grim satisfaction, the earl replaced his belt and left his wife to sob into the coverlet.

Servants opened the door to the marshaling yard beyond as Thomas Percy, Baron Egremont, walked out. The noise of hundreds of men crashed over him under the blue sky, making his heart beat faster. With an irritated glance, he saw members of his own staff were already there, suborned by his father and waiting patiently for him. They carried armor and his weapons, while other men worked on Balion, the great black charger he had bought for a ruinous price the previous year. It seemed his father had been in no doubt as to the outcome of their conversation. Thomas frowned as he approached the group within the milling mass of men, taking in the sheer complexity of the scene. Far above them all, he could hear his mother screaming like a butchered sow, no doubt as the old man laid into her yet again. Thomas felt only irritation that she should intrude so on his thoughts. He was forced to look down rather than suffer the un- wanted intimacy of other men’s eyes. With each new wail, they either grinned or winced, while his anger at her only grew. The rise of the Neville family ate at his father, ruining the old man with suspicions and rages when the earl should have been enjoying quiet years and turning over the running of estates to his sons. As the sounds died away at last, Thomas looked up to the window of his father’s private rooms. It was typical of the old man to set his plans in motion for days or weeks without even bothering to tell his own son what he intended.

With quick, neat motions, Thomas removed his leather breast- plate and cloak, stripping down in the yard to hose and undertunic, already showing patches of dark sweat. There was no modesty there and scores of young men joked and shouted to one another as they hopped with an armored boot, or called for some piece of their equipment that had found its way into someone else’s spot. Thomas seated himself on a high stool, sitting patiently while his servants worked to fasten the padded gambeson jerkin and strap him into each plate of his personal armor. It fitted him well, and if the scars and marks were from the training yard rather than a battle, it was still a good set, well worn. As he raised his arms for the breastplate to be strapped on, he glared at the marks of a scourer, the metal dulled by some kitchen girl working it like a pot. The blue and yellow crest had been obliterated and he craned his neck to see his sword where it lay ready to be handed to him. Thomas swore softly then, seeing the fine enamel badge had been chiseled from the guard. It was on his father’s orders, of course, but he had carried that sword since his twelfth birthday and it hurt to see it damaged.

Piece by piece, his armor was put on, until he stood, feeling the wonderful sense of strength and invulnerability it brought. Lord Egremont reached for the helmet his steward held out reverently to him. As he rammed it onto his head, Thomas heard the voice of his father’s swordmaster echoing across the marshaling yard.

“When the gate opens, we are gone,” Trunning shouted to the gathered men. “Be ready, for there’ll be no riding back like lady’s maids after a dropped glove. No personal servants beyond those with mounts who can hold a sword or a bow and keep up. Dried beef and raw oats, a little ale and wine, no more! Provisions for six days, but ride light, or be left behind.”

Trunning paused, his gaze sweeping across the knights and men as he readied himself to give another half-dozen instructions. He caught sight of the Percy son and moved on the instant to come to his side. It gave Thomas some small satisfaction to look down on the shorter man.

“What is it, Trunning?” he said, deliberately keeping his voice cold. Trunning didn’t reply at first, just stood, looking him over and chewing the white mustache that drooped over his lips. His father’s swordmaster had trained both Percy sons in weapons and tactics, beginning so early in their lives that Thomas could not remember a time he had not been there, shouting in anger at some poor stroke, or demanding to know who had taught him to hold a shield “like a Scots maid.” With no effort of memory, Thomas could recall five bones broken by the red-faced little man over the years: two in his right hand, two cracked forearms, and a small bone in his foot where Trunning had once stamped down in a tussle. Each one had meant weeks of pain in splints and withering scorn for every groan he made while they were bound. It was not that Thomas hated or even feared his father’s man. He knew Trunning was intensely loyal to the house of Percy and Northumberland, like a particularly savage old hound. Yet for all the differences in their station, Thomas, Lord Egremont, could not imagine the man ever accepting him as an equal, never mind his superior. The very fact that his father had placed Trunning in command of the raid was proof of that. The pair of old bastards were cut from the same rough cloth, with not a drop of kindness or mercy in either of them. It was no wonder they got on so well.

“Your father has talked to you, then? Told you the way of it?” Trunning said at last. “Has he said to mark my orders in all things, to bring you safe home with a couple of new scratches on that fine armor of yours?”

Thomas repressed a shudder at the man’s voice. Perhaps the result of so many years bawling across fields and streets at those he trained, Trunning was always hoarse, his spoken words mingling with deep, wheezing breaths.

“He has told me you will command, Trunning, yes. To a point.” Trunning blinked lazily, weighing him up.

“And what point would that be, my noble lord Egremont?”

To his dismay, Thomas felt his heart hammer in his chest and his own breathing grow tight. He hoped the swordmaster could not sense the strain in him, though it was near certain after knowing him for so long. Nonetheless, he spoke firmly, determined not to let his father’s man rule him.

“The point where you and I disagree, Trunning. The honor of the house is mine to guard and protect. You may give orders to march and to attack and so forth, but I will consider the policy, the aims of what we are about.”

Trunning stared at him, tilting his head and rubbing at a spot above his right eye.

“If I tell your father you are chafing, he’ll make you come along as a potboy, if at all,” he said, smiling unpleasantly. He was surprised when the young man turned to face him fully, leaning down.

“If you carry tales to the old man, I will stay. See how far you get from the gates without a son of the Percy family at the head. And then, Trunning, you’ll have made an enemy of Egremont. Now I’ve told you my terms. You do as you please.”

Thomas deliberately turned back to his servants then, beckoning for them to adjust and add a drop of oil to his visor. He felt Trun- ning’s gaze and his heart continued to race, but he was certain of himself, in that one thing. He did not look round when the sword- master stalked off, not even to see if Trunning would march into the castle and take his complaints to his father. Lord Egremont lowered his visor to conceal his expression. His father and Trunning were both old men and, for all their will and spite, old men fell away in the end. Thomas would take the archers and the swordsmen against his uncle’s wedding party, either with Trunning or without him it mattered not at all. He looked again at the small army his father had called to Percy service. Hundreds were no more than town men, summoned by their feudal lord. Yet whether they worked as smith, butcher, or tanner, each of them had trained with ax or bow from their earliest years, developing skills that would make them useful to a man like Earl Percy of Alnwick. Thomas smiled to himself, raising his visor once again.

“Form on the gate!” he roared at them. From the corner of his eye, he saw Trunning’s trim shape jerk round, but Thomas ignored him. Old men fell away, he told himself again, with satisfaction. Young men came to rule.

Chapter 2

Derry Brewer was in a foul mood. The rain poured down in sheets, drumming against the bald dome of his head. He had never realized before how a good head of hair really

soaked up the rain. With his pate so cruelly exposed, the dreadful pattering made his skull ache and his ears itch. To add to his discomfort, he wore a sodden brown robe that slapped wetly against his bare shanks, chafing the skin. His head had been shaved by a fairly expert hand just that morning, so that it still felt new and sore and appallingly exposed to the elements. The friars trudging along with him were all tonsured, the white circles of scalp gleaming wetly in the gloom. As far as Derry could tell, none of them had eaten a morsel of food since dawn, though they had walked and chanted all day.

The great walls of the royal castle lay ahead up Peascod Street as they rang their bell for alms and prayed aloud, the only ones foolish enough to stand out in the rain when there was shelter to be had. Windsor was a wealthy town; the castle it existed to serve was only twenty miles from London, like half a dozen others around the capital, each a day’s march apart. The presence of the king’s household had brought some of the very best goldsmiths, jewelers, vintners, and

mercers out of the capital city, eager to sell their wares. With the king himself in residence, more than eight hundred men and women in his service swelled the crowds and raised the prices of everything from bread and wine to a gold bracelet.

In his sour humor, Derry assumed Franciscan friars would be attracted by the f low of coins as well. He was still unsure if his grubby companions were not just rather clever beggars. It was true Brother Peter harangued the crowds for their iniquity and greed, but the rest of the friars all carried knives to sell as well as begging bowls. One wide-shouldered unfortunate seemed resigned to his role among them as the carrier of a large grindstone. Silent Godwin walked with it on his back, tied on with twine and so bowed down that he could hardly look up to see where he was going. The others said he endured the weight as penance for some past sin and Derry had not dared ask what it had been.

At the intervals of abbey services throughout the day, the group would stop and pray, accepting offers of water or homebrewed beer brought out to them as they assembled a treadle and set the stone spinning, sharpening knives and blessing those who passed over a coin, no matter how small. Derry felt a pang of guilt about the tight leather purse he wore snug and close to his groin. He had silver enough in there to feed them all to bursting, but if he brought it out, he suspected Brother Peter would give it away to some undeserving sod and leave the monks to starve. Derry puffed out his cheeks, wiping rain from his eyes. It washed down his face in a constant stream, so that he had to blink through a blur.

It had seemed like a good idea to join them four nights before. As a result of their humble trade, the group of fourteen monks were all armed. They were also used to nights on the road where thieves might try to steal even from those who had nothing. Derry had been lurking in the stables of a cheap tavern when he’d overheard Brother Peter talking about Windsor, where they would pray for the king’s recovery. None of them had been surprised another traveler would want to do the same, not with the king’s soul in peril and all the country so beset with violent men.

Derry sighed to himself, rubbing hard at his face. He sneezed explosively and caught himself opening his mouth to curse. Brother Peter had taken a stick to a miller just that morning for shouting a blasphemy on the open street. It had been Derry’s pleasure to see the meek leader of the group exercise a wrath that would have made him a minor name in the fight rings of London. They’d left the miller in the road, his ears leaking blood from the battering he’d received, his cart overturned and his f lour bags all broken. Derry smiled at the memory, glancing over to where Brother Peter walked, sounding his bell every thirteenth step so that it echoed back from the stone walls at the top of the hill.

The castle loomed in the rain, there was no other way to describe it. The massive walls and round baileys had never been breached in the centuries since the first stones had been laid. King Henry’s stronghold squatted over Windsor, almost another town within the first, home to hundreds. Derry stared upward, his feet aching on the cobbles.

It was almost time to leave the little group of monks and Derry wondered how best to broach the subject. Brother Peter had been astonished at his request to be tonsured as the other men. Though they accepted it for themselves as a rebuke of vanity, there was no need at all for Derry to adopt the style. It had taken all Derry’s persuasive skill before the older man allowed he could do as he pleased with his own head.

The young friar who had taken a razor to Derry’s thick hair had managed to c

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...