- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

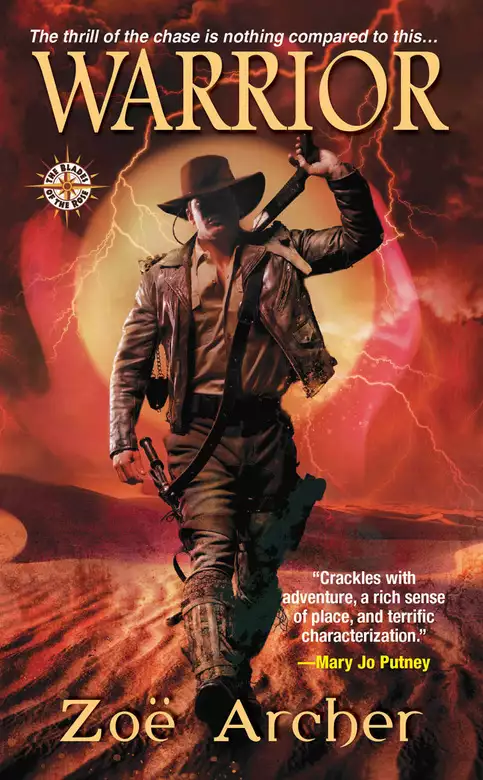

“An innovative and exciting romantic adventure with just the right touch of the paranormal.”—Jennifer Ashley, New York Times bestselling author To most people, the realm of magic is the stuff of nursery rhymes and dusty libraries. But for Capt. Gabriel Huntley, it’s become quite real and quite dangerous . . . In Hot Pursuit . . . The vicious attack Capt. Gabriel Huntley witnesses in a dark alley sparks a chain of events that will take him to the ends of the Earth and beyond—where what is real and what is imagined become terribly confused. And frankly, Huntley couldn’t be more pleased. Intrigue, danger, and a beautiful woman in distress—just what he needs. In Hotter Water . . . Raised thousands of miles from England, Thalia Burgess is no typical Victorian lady. A good thing, because a proper lady would have no hope of recovering the priceless magical artifact Thalia is after. Huntley’s assistance might come in handy, though she has to keep him in the dark. But this distractingly handsome soldier isn’t easy to deceive . . . Praise for the Blades of the Rose novels “Crackles with adventure, a rich sense of place, and terrific characterization.”—Mary Jo Putney, New York Times bestselling author “The action explodes on page one and the pace never lets up.”—Ann Aguirre, New York Times bestselling author “A sexy mix of magic and mystery.”—Caridad Piñeiro, New York Times bestselling author “Zoe weaves a delightful spell . . . cleverly blending history and magic in new, delightful ways.”—Elizabeth Vaughan, USA Today bestselling author

Release date: September 1, 2010

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Warrior:

Zoe Archer

Gabriel Huntley hated an unfair fight. He had hated it as a boy in school, he had hated it during his service in Her Majesty’s army, and he hated it now.

Huntley ducked as a fist sailed toward his head, then landed his own punches on his attacker in quick succession. As his would-be assailant crumpled, unconscious, to the ground, Huntley swung around to face another assault. Three men coming toward him, and quick, cold murder in their eyes. Their numbers were thinning, but not by much. Huntley couldn’t keep a smile from curving in the corners of his mouth. Less than an hour in England, and already brawling. Maybe coming home wouldn’t be so bad.

“Who the hell is this bloke?” someone yelped.

“Dunno,” came the learned reply.

“Captain Gabriel Huntley,” he growled, blocking another punch. He rammed his elbow into someone’s gut. “Of the Thirty-third Regiment of Foot.”

His ship had docked that night in Southampton, bringing him back to British shores after fifteen years away. As he had stood at the bottom of the gangplank, his gear and guns strapped to his back, he’d found himself strangely and uncharacteristically reticent. He couldn’t seem to get his feet to move forward. After years of moving from one end of the British Empire to the other, following orders sent down through the chain of command, he was finally able to decide on his fortune for himself. It was a prospect that he had been looking forward to for a long while. After resigning from his captaincy, he had booked passage on the next ship to England.

However, that idea had already begun to pale on the voyage back, with days and weeks of shipbound idleness leaving his mind to pick and gnaw at whatever fancy struck him. Yes, he’d been born in England and lived there for his first seventeen years—in a dismal Yorkshire coal mining village, more specifically. But nearly the other half of his life had been spent on distant shores: the Crimea, Turkey, India, Abyssinia. England had become no more than a far away ideal of a place recreated again and again in company barracks and officers’ clubs. He had barely any family and few friends in England besides Sergeant Alan Inwood. The two men had fought side-by-side for years, and when a bullet had taken Inwood’s leg, the trusty sergeant returned to England. But he’d written Huntley steadily over the years.

In Huntley’s pocket was Inwood’s latest missive. He’d memorized it, having read the letter over and over again on the voyage to England. It promised a job working with Inwood as a textile agent in Leeds. An ordinary, steady life. The prospect of marriage. Leeds, Inwood claimed, had an abundance of nice, respectable girls, daughters of mill owners, looking for husbands. Huntley could have a job and a wife in a trice—if he wanted.

Huntley knew how to fight in the worst conditions nature and man could create. Monsoons, blizzards, scorching heat. Bayonets, sabers, revolvers, and rifles. He’d eaten hardtack crawling with maggots. He’d swallowed the most fetid and foul water when there had been nothing else to drink. None of it had broken him. He had nothing left to fear. Yet the idea of truly settling down, finding, good Lord, a wife, it turned a soldier’s blood to sleet.

After the ship had docked, Huntley had lingered at the foot of the gangplank, jostled on all sides by the shoving and cursing mass of the crowded dock. He had tried to make himself take the first step toward his new life, an ordinary life, and found that he couldn’t.

Not yet, at any rate. Instead of rushing toward the inn where mail coaches waited to take passengers to English towns and cities near and far, Huntley had begun to walk in the opposite direction. Though he’d been at sea for months, he needed more time. Time to think. Time to plan. Time to grow accustomed to his strange and foreign homeland. Time for at least one pint.

He walked without real purpose, winding his way through the maze of narrow, lamplit streets that led from the pier. He hadn’t gone more than thirty yards from the docks when the crowds thinned, leaving him on a quiet, dark street bathed in seaside mists. A large orange tabby cat slunk by, heading for the docks and promises of fish. At the end of the street was a tiny pub, casting yellow light onto the slick stone pavement outside, and full of raucous laughter and rough talk, not unlike the kind that could be found in any military barracks.

It seemed like heaven.

Huntley had started toward the pub, the desire for a pint of bitters strong in his mouth. At least that part of him was a true Englishman. As he strode toward the welcoming chaos, his soldier’s senses alerted him to trouble close at hand. In the gloom of an alleyway leading off the street, he heard it first, then saw it, the sight that turned his blood to fire and overrode all thought: one man, badly outnumbered, wounded and staggering, as half a dozen men attacked him and several others stood nearby, ready to throw themselves into the fray should they be needed. He knew at once that what was happening was wrong, and that he had to help the injured man.

Huntley had launched himself into the fight, needing to even the odds.

Three men now came at him, throwing him against a damp brick wall. Fortunately, his pack kept him from smashing his head against the bricks. Two men took his arms while the third pinned his middle. Before any of them could land a punch, Huntley slammed his knee up into the chest of the man pinning him, knocking the air out of him with a hard gasp, then he wedged the heel of his boot against the man’s ribs and shoved. Winded as he was, the man could only scrabble for a hold before being thrown into a pile of empty crates, whose sharp edges made for a less than cushioned fall as the crates broke apart. Huntley swiftly rid himself of the other two men.

He considered going for his rifle or revolver, but quickly discarded the idea. Firearms in tight quarters such as alleyways were just as dangerous to whomever wielded them as they were to the intended targets. Striking distance was too close, and it would be far too easy for someone to grab the weapon from him once it was cocked and turn it on him.

Fists it was, then. Huntley had no qualms with that.

Huntley sprinted toward where the victim was being pummeled by two men. As Huntley came to the victim’s aid, one of the attackers managed to graze a fist against Huntley’s mouth. But it was nothing compared to the damage the victim had taken. Blood was splattered all over the man’s shirt and waistcoat, his jacket was ripped at the seams, and his face was swollen and cut. Huntley had been in enough brawls to know that if the victim made it through the fight, his face would never be the same, even under his gingery beard. He was still swinging, though, bless his soul, as he staggered and struggled.

“I don’t like bullies,” Huntley rumbled. He grabbed the man who’d just punched him and gripped him by the throat, squeezing tightly.

The man scrabbled to pry Huntley’s fingers from around his neck, but the hand that had grown strong gripping a rifle through fifteen years of campaigns couldn’t be removed. Still, the man managed to choke out a few words.

“Whoever…you are…,” he rasped, “walk…away. Isn’t your…fight.”

Huntley grinned viciously. “That’s for me to decide.”

“Fool,” the man wheezed.

“Perhaps,” Huntley answered, “but since these are my fingers around your throat”—and here he tightened his hold, squeezing out an agonized gargle from the other man—“it wouldn’t be wise to start tossing out names, would it?”

The man’s answer never came. From behind Huntley, an abbreviated cry shot out, sharp and dreadful. Turning, Huntley saw a flash of metal gleam in the half light of the alley. One of the attackers stepped back from the victim, a long and wicked blade streaked with bright red in his hand. Blood quickly began to soak through the front of the victim’s waistcoat and run through his fingers as he pressed against the wound in his stomach.

“Morris isn’t going anywhere,” the knife-wielding man said. His accent was clipped and well-born, as neatly groomed as his gleaming blond hair and moustache. He seemed comfortable with the red-smeared blade in his hand, despite his aristocratic air. “Let’s go,” Groomed Gent commanded to the other men.

Huntley spent half a moment’s deliberation on whether to go for the upper cruster with the knife or attend to the fellow who’d been stabbed, Morris. He released his grip on his captive’s throat at once and barely caught Morris before the wounded man collapsed to the ground.

The attackers quickly fled from the alley, but not before someone asked, pointing at their unconscious comrade slumped nearby, “What about Shelley? And him,” gesturing toward Huntley.

“Shelley’s on his own,” Groomed Gent barked. “And the other one knows nothing. We have to move now,” he added with a snarl. And before Huntley could stop them, every last one of the assailants disappeared into the night, leaving him cradling a dying man.

And he was dying. Of that, Huntley had no doubt. He’d seen similar wounds on the battlefield and knew that they were always fatal. Blood seeped faster and faster through the gash in Morris’s abdomen. It would take something akin to a miracle to stop the advance of death, and Huntley had no store of miracles in his pack.

He gently lowered himself and Morris to the ground. “Let me fetch a surgeon,” he said. He slipped the straps of his pack from his shoulders so the weight eased off.

“No,” gasped Morris. “No use. And time’s running out.”

“At the least, I can get the constabulary,” Huntley said. He recalled the icy cruelty of the knife-wielding gentleman, the sharp angles of his face that likely came directly from generations of similarly ruthless people’s intermarrying and breeding. “I had a decent enough look at those men’s faces. I could describe most of them, see them brought to justice.”

A mirthless smile touched Morris’s lips. “That would be the fastest way for you to wind up dead in an alleyway, my friend.”

Huntley wondered who those men were, that attacked a gentleman in an alley like common footpads but had enough power for retribution. Perhaps a criminal organization. With a well-heeled gentleman as a member of its ranks. Was such a thing possible? He couldn’t think on it now. Instead, knowing that his face would be the last that Morris would ever see and wanting to make the remaining time more personal, he said, “Name’s Huntley.”

“Anthony Morris.” The two shared an awkward handshake, and Huntley’s hand came away smeared crimson.

“Is there anything I can do for you, Morris?” he asked. Not much longer now, if the dark blood drenching Morris’s clothing was any indication.

Frowning, Morris started to speak, but then Huntley’s attention was distracted. The remaining attacker, who had been slumped unconscious against a wall, had somehow come to without making a sound. But now he was crouched nearby, whispering into his cupped hands. Looking closer, Huntley was able to see that the man held something that looked remarkably like a small wasps’ nest—but it was made of gold. The close air of the alley was suddenly filled with a loud, insistent droning as, incredibly, the golden nest began to glow.

Not once, through the many places around the world he had been posted, had Huntley ever seen or heard anything like this, and he had seen some of the most incomprehensible things anyone could envision. He was transfixed, his mind immobilized by the sight.

The buzzing grew louder still, the nest glowed brighter as the man whispered on. Then something appeared in an opening in the nest, a tiny shine of a metallic wasp. Of its own volition, Huntley’s hand came up, trying to reach out toward the mysterious spectacle. A line of wasps suddenly shot from the nest, directly toward Huntley and Morris. And Huntley still could not move.

With a grunt and groan, Morris managed to shift himself around in Huntley’s arms and shove him down to the ground. They both splayed out onto the slippery pavement. And just in time. Dozens of wasps slammed into the wall behind them, their noise and impact against the brick like a round of bullets shot from a Gatling gun. Chips of mortar and brick rained down onto Huntley as he raised his arm to shield himself and Morris. He quickly reached out and grabbed a wooden board from a crate that had been broken apart in the fight. Several nails stuck out from one end of the board, and this he hurled at the man with the wasps’ nest. The man yelped in surprised pain as the board hit him in the head, then staggered to his feet and scurried away, cradling the nest and pressing a palm to his bleeding scalp. It wouldn’t be difficult to catch up with the wounded man, but in those few minutes, Morris would be dead, and Huntley had seen enough death to know it was better with someone, anyone, beside you.

He might have joined Morris in the afterlife, though. Huntley looked up at the wall behind him. Two dozen neat holes had been punched into the solid face of the brick. Exactly where his head had been. If Morris hadn’t pushed him, those holes would now be adorning his own skull and his brains would be nicely splattered across half of Southampton, where they wouldn’t do him much good.

“What the hell was that?” he demanded from Morris. Huntley heaved himself up into a sitting position, with Morris leaning against him. “Wasps like bullets? From a glowing golden nest?”

Morris coughed, sending another bubble of blood through his fingers. “Never mind that. Something I have to tell you. A message to deliver. Must be delivered…personally.”

“Of course.” Huntley owed Morris his life. That bound him to his service. It didn’t matter that, in a matter of minutes, Morris would be dead. It was an unbreakable rule, one that was never questioned, never doubted. Honor was held at a premium when the rest of the world went to hell. “Have you a letter? Something I should write down?” There were a few books in his pack, but of any of these he would gladly sacrifice a few pages to transcribe Morris’s message.

Morris shook his head weakly. “Can’t write the message down. Even so, there are no mail routes to deliver it.”

A message that could not be written. A destination beyond the all-encompassing reach of the British postal service. Things began to get stranger and stranger. Huntley started to wonder if, perhaps, he was lying drunk in a gutter somewhere, already deep in his return to England alcohol binge, and everything that had happened, was happening, was a whiskey-induced delusion. “Where’s it going?”

“To my friend, Franklin Burgess.” Morris gritted his teeth as a wave of pain moved through him, and Huntley did his best to comfort him, brushing clammy strands of hair back from Morris’s forehead. “In Urga. Outer Mongolia.”

“That is…far,” Huntley managed after he found his voice.

Another ghostly smile curved Morris’s mouth. “Always is. Was headed to a ship to take me there when,” he nodded toward the horrible wound in his stomach as his smile faded. With his free hand, he clutched at Huntley’s jacket. The strength left in Morris’s grip surprised Huntley, but Morris was growing more and more agitated. Huntley tried to calm him, but to no avail. Morris became nearly frantic, spending the last of his energy as he tugged Huntley closer. “Please. You must deliver the message to Burgess. Thousands of lives at stake. More. Many more.”

Huntley hesitated. Inwood’s letter was in his pocket. The promise of a quiet future beckoned. What Morris asked was huge, a deviation from plans to settle in Leeds, and yet, to Huntley’s mind, an adventure into unknown lands was infinitely preferable to tranquil stability. The fact that he’d thrown himself into a fight minutes after arriving in England told him so. Intelligent, probably not, but Huntley never put much stock in dry logic. And Morris had saved his life, the ultimate obligation. He could not refuse the dying man.

He said, “Give me the message. I’ll deliver it to him.”

Morris seemed momentarily surprised that Huntley had agreed, but then pulled him down so his ear was level with Morris’s mouth. In words barely audible, he whispered into Huntley’s ear. Huntley didn’t quite know what to expect, but certainly not the two lines of nonsense that Morris faintly gasped. How could the lives of thousands or more rest on something not even Edward Lear would comprehend?

“Repeat them back to me,” Morris insisted. He was waxen and pale, his lips growing stiff and awkward. The blood from his wound was slowing now. The source was nearly tapped out.

Feeling not a little ridiculous, Huntley repeated Morris’s message—three times at Morris’s urging—until the dying man was satisfied.

“Good. You must leave. Tonight. Next ship leaves. Two weeks. Too late.”

Huntley, who hadn’t been relishing the idea of his return to England, was still surprised by the speed with which he was supposed to leave it. He had some money from his army discharge, but he doubted he had enough to pay for a trip to the other side of the world. Soldiering was not the way any man could make his fortune, though perhaps that was the reason it attracted such a variety of reckless fools, including himself. As if anticipating his objections, Morris added, “In my coat pocket. My papers. Take my place on the ship.”

His head still swimming with all that he had seen and heard within the span of an hour, Huntley could only nod. Then a thought occurred to him. “This man, Burgess,” he said. “I doubt he’ll trust me if I show up at his door with some ridiculous…er, coded message, and say that you’ve…” He let his words trail off, even though it was clear that they both knew Morris wasn’t going to make it out alive from the alley.

Morris’s eyes were dull and sinking into his face. Huntley could barely hear him when he said, “Waistcoat inside pocket.”

As carefully as he could, Huntley reached into the small pocket sewn into the lining of Morris’s waistcoat. He pulled from the pocket a small circular metal object that turned out to be a compass. In the dimness of the alley, he was just able to see that the exterior of the compass was covered with minute writing in languages Huntley could not read, though he suspected they were Greek, Hebrew, and, yes, Sanskrit, of which he had a small knowledge. He opened the lid. Each point of the compass was represented by a different blade: the Roman soldier’s pugio, the European duelist’s rapier, the curved scimitar of the Near East, and the deadly serpentine form of the kris from the East Indies. A classic English rose lay at the center of the compass. Huntley realized that the compass was exceptionally old, with the heaviness of precious metal. Whispers of the past seemed to curl from it like perfumed smoke, and the lure of distant shores beckoned from within it, more powerful than any siren’s call. It was extraordinary.

“Give that. To Burgess.” Morris’s breath grew even more shallow. “Say to him, ‘North is eternal.’ He’ll know.”

“I’ll do that, Morris,” Huntley said, straight and solemn.

“Thank you,” he gasped. “Thank you.” He seemed to relax at last, no longer fighting the inevitable.

“Is there someone else I should tell about you? Some family?”

“None. Only family I have. Will learn soon enough.” And with those words, a final spasm passed through Morris, the body’s last struggle to cling to the knowable world. He arched up, almost flinging himself from Huntley’s arms as a strangled sound ripped from his throat. Then he fell back, eyes open, and Huntley knew it was done.

He looked down at the dead man’s face. Morris couldn’t have been more than forty or forty-five, a hale man who, though he wasn’t a soldier by trade, had kept himself well-conditioned. He was dressed finely, without ostentation, the quality of his clothing revealing a certain level of status few, including Huntley himself, would enjoy. Shame to have Morris’s life end so abruptly, shame to meet death in an ignominious, dirty alley, the victim of an unfair fight.

Huntley reached down and closed Morris’s eyes. He sighed. No, he never quite got used to death, no matter how familiar it had become.

Two hours later saw Huntley standing on the deck of the Frances, watching the lights of Southampton grow smaller and fainter in the dark of night.

Good-bye, again, he thought.

After Morris had expired, Huntley took the travel papers from the dead man’s pocket and saw that the ship on which he was intending to sail would be leaving shortly. There wouldn’t be time to call for the police, since a lengthy inquiry would surely follow with the real possibility that Huntley would be forbidden to leave the country until the matter of Morris’s death had been resolved. That could take weeks, weeks that Morris had assured him he did not have. So Huntley carefully lay Morris’s body upon the ground and used the man’s coat to cover his face. His own clothing was utterly soaked in Morris’s blood. Getting on a ship in gore-drenched clothes was not an attractive or likely option. He had gone through his pack and found a fresh change, wrapping the ruined garments in a small blanket and stuffing them back into his pack. No point in leaving any clues to his identity when the constabulary did finally discover Morris.

Huntley had felt not a little guilty, leaving Morris alone in that dank alley, but there was nothing to be done for it. When he had presented the papers to the steamship Frances’s first mate, he was taken at his word to be Anthony Morris, of Devonshire Terrace, London, and was shown to a cabin far more luxurious than the one Huntley had voyaged in on his return. As the ship raised anchor and prepared to sail, the elegance of the cabin, with its brass fixtures and framed prints, could not compete with the restlessness of Huntley’s heart, and he found himself standing on the deck with a few of the other passengers, watching the shore of England recede.

“We’re going to Constantinople.” Huntley looked over and saw a young, genteel woman at his shoulder beaming at him. A sharp-eyed mama stood nearby, watching the flirtation of her charge, but had evidently gleaned enough information about “Mr. Morris” to render him an appropriate target for a girl’s shipboard romance. Huntley felt the stirrings of panic.

“This is my first international voyage,” the girl continued brightly. “I cannot wait to get away from boring old Shropshire.” She waited, smiling prettily, for his suitably charming response. A light sweat beaded on his back.

“Knew a fellow from Constantinople,” Huntley finally said. “Excellent shot. I once saw him shoot a mosquito off a water buffalo’s rump.”

The girl gaped at him, flushed, then turned and walked away as quickly as she could toward the protective embrace of her mother. After the mother glared at him, both females disappeared. Presumably they were off to spread the word that Mr. Morris was the most uncouth and ill-mannered man on the ship, including the one-eyed cook who was both a drunkard and an atheist.

Perhaps a little more time away from England would be for the best. Huntley would have to start his bride hunt when he came back, and, if that last exchange was any indicator, he sorely needed some refinement where his conversation with ladies was concerned. Fifteen years out of the company of respectable women tended to leave a mark on one’s manners.

He had an even larger enigma on his hands than the workings of the feminine mind. Reaching into his pocket, Huntley pulled out the remarkable compass and stared at its face. He rubbed his thumb over the writings that covered the case as if trying to decipher them by touch, then flipped open the lid to look at the four blades that comprised the four directions. Priceless and old, even he could see that. And full of mystery.

Yes, things were about to get very interesting. No Leeds and job and wife, at least, not yet. A wry smile touched his lips, and he turned his back on the receding English coastline to make his way back down to his cabin.

Urga, Outer Mongolia. 1874. Three months later.

An Englishman was in Urga.

The town was no stranger to foreigners. Half of Urga was Chinese; merchants and Manchu officials dealt in commerce and administering the Qing empire. Russians, too, had a small foothold in the town. The Russian consulate was one of the only actual buildings in a town otherwise almost entirely comprised of felt ger tents and Buddhist temples. So it was not entirely unexpected to hear of an outlander in town.

But Englishmen—those were much more rare, and, to Thalia Burgess, more alarming.

She hurried through what passed for streets, jostling past the crowds. Strange to be amongst crowds in a land that was mostly wide open. Like a typical Mongol, Thalia wore a del, the three-quarter-length robe that buttoned at the right shoulder to a high, round-necked collar, a sash of red silk at her waist. Trousers tucked into boots with upturned toes completed her ordinary dress. Though she was English, as was her father, they had both been in Mongolia so long that their presence was hardly remarked upon even by the most isolated nomads. No one paid her any mind as she made her way through the labyrinth of what approximated streets in Urga, toward the two gers she and her father shared.

She tried to fight the panic that rose in her chest. Word had reached her in the marketplace that an Englishman had come to this distant part of the world, which, in and of itself troubled her. But the worst news came when she learned that this stranger was asking for her father, Franklin Burgess. Her first thought was to get home at once. If the Heirs had come calling, her father would be unable to defend himself, even with the help of their servants.

As she hurried, Thalia dodged past a crowd of saffron-robed monks, some of them boys training to become lamas. She passed a temple, hearing the monks inside chanting, then stopped abruptly and threw herself back against the wall, hiding behind a painted pillar.

It was him. The Englishman. She knew him right away by his clothing—serviceable and rugged coat, khaki trousers, tall boots, a battered broad-brimmed felt hat atop his sandy head. He carried a pack, a rifle encased in a scabbard hanging from the back. A pistol was strapped to his left hip, and a horn-handled hunting knife on his right hip. All of his gear looked as though it had seen a lot of service. This man was a traveler. He was tall as well, half a head taller than nearly everyone in the crowd. Thalia could not see his face as he walked away from her, had no idea if he was young or old, though he had the ease and confidence of movement that came from relative youth. In his current condition, her father couldn’t face down a young, healthy, and armed man with an agenda.

Thalia pushed away from the pillar and dodged down a narrow passage between gers. Whoever he was, he didn’t know Urga as she did, and she could take shortcuts to at least ensure she arrived at her home before him. Thalia had been to Urga many times, and, since her father’s accident, they had been here for months. The chaos still did not make sense to her, but it was a familiar chaos she could navigate.

As she raced past the light fences that surrounded the tents, she had to thread past herds of goats and sheep, horses and camels, and dodge snarling, barely tamed dogs that stood guard. She snarled at a dog who nipped at her leg, causing the animal to fall back. Nimbly, she leapt over a cluster of children playing. As Thalia rounded past another ger, she caught one more glimpse of the Englishman, this time just a brief flash of his face, and, yes, he was young, but she did not see enough to ascertain more.

Perhaps, she tried to console herself, he wasn’t an Heir, merely a merchant or some scientist come to Outer Mongolia to ply his trade, and in search of the language and faces of his homeland. She smiled grimly. It didn’t seem likely. No one came to Urga without a specific purpose. And the Englishman’s purpose was them.

At last, she reached the two gers that made up the Burgess enclosure. Thalia burst through the door of her father’s tent to find him reading. The furnishings here were exactly as they might be in any Mongol’s ger, with only books in English, Russian, and French to indicate that she and her father were from another country. She allowed herself a momentary relief to see him unharmed and alone. Franklin Burgess was fifty-five, his black hair and beard now dusted with silver, green eyes creased in the corners with lines that came from advancing age and nearly a lifetime spent out of doors. He was her sole parent, had been for almost her entire twenty-five years, and Thalia could not imagine her world without him. She might as well try to picture what life might be like without the sun. Cold. Unbearable.

At her hurried entrance, he set aside his book and peered at her over his spectacles.

“What is it, tsetseg?” he asked.

Thalia quickly explained to him what she had learned, and her father frowned. “I saw him,” she added. “He didn’t know where he was going, but he wasn’t panicking. He seemed used to dealing with unfamiliar situations.”

“An Heir, perhaps?” Franklin asked as he removed his glasses.

She shook her head. “I could not tell.”

With more calm than she felt, he said, “Be a dear and hand me my rifle.” Thalia hastily retrieved her father’s gun, one that could open up a nicely sized hole in anyone who sought mischief. Franklin checked to be sure it was loaded, then tucked it behind the chair in which he sat, within easy reach. He was careful not to disturb his right leg, propped in front of him on a low stool. The bones were finally beginning to repair themselves after the accident with the horses, and neither Thalia nor her father wanted any kind of setback to the healing process, not when it had taken so long for the nasty double break to mend at all. It was amazing that, after being trampled by a herd of horses, her father had sustained only a few cuts and bruises in addition to his broken leg. It could have been much worse.

“We don’t know if he is an Heir, though,” Franklin said. He looked over to the kestrel they kept, perched quietly near the bookcase. The bird didn’t seem uneasy, a good sign. “Just in case it isn’t an Heir, perhaps it would be wise if you…” He gestured toward her del. His own clothes were a mixture of European and Mongol, and while it might be more common for European men to adopt some aspect of native dress outside of their home country, it was entirely different for women. Should this strange Englishman turn out to be nothing more than a trader or scholar, it wouldn’t do to raise suspicions. To the outside world, Franklin Burgess and his daughter Thalia were simply anthropologists collecting folklore for their own academic pursuits.

Thalia looked down at herself and grimaced. “The things I do for the Blades,” she muttered, and her father chuckled. She gave him a quick kiss on his bristly cheek and rushed into her ger. Most Mongolian families did not have separate gers for parents and children, but as soon as Thalia had turned thirteen, her father thought it best to stray from native custom and give his daughter some privacy.

“Udval,” she called to her female servant in Mongolian, “can you please grab my dress? The English one? It’s in the green chest. At the bottom.”

Thalia began pulling off her del, her boots to follow, as the woman set aside her brewing of milk tea to look for the seldom-used gown.

“Here is your dress, Thalia guai,” Udval said, holding up the pale blue gown in question. She looked at it, then looked back at Thalia, doubt plainly written on her face. “I think, perhaps, it has grown smaller.”

Standing in the middle of her ger, wearing a chemise and drawers, Thalia fought back a sigh. “No, it has stayed the same, but I have gotten bigger.” Three inches taller, to be more precise. The last time Thalia had worn that gown, she had been fifteen, and though she had been a relatively average-sized girl, she was now a tall woman who stood nose-to-nose with most men. S. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...