- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

"Wake of Vultures will kick your a** up one page and down the other." -- io9

Nettie Lonesome dreams of a greater life than toiling as a slave in the sandy desert. But when a stranger attacks her, Nettie wins more than the fight.

Now she's got friends, a good horse, and a better gun. But if she can't kill the thing haunting her nightmares and stealing children across the prairie, she'll lose it all -- and never find out what happened to her real family.

Wake of Vultures is the first novel of the Shadow series featuring the fearless Nettie Lonesome.

The Shadow series

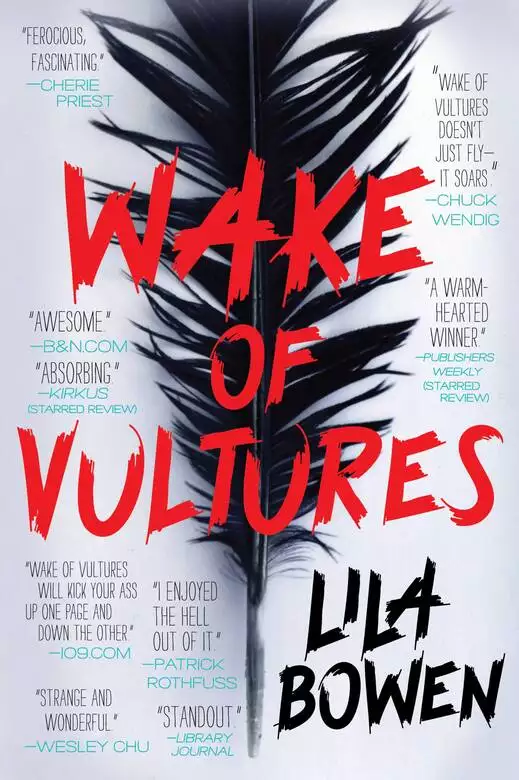

Wake of Vultures

Conspiracy of Ravens

Release date: October 27, 2015

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Wake of Vultures

Lila Bowen

Nettie Lonesome had two things in the world that were worth a sweet goddamn: her old boots and her one-eyed mule, Blue. Neither item actually belonged to her. But then again, nothing did. Not even the whisper-thin blanket she lay under, pretending to be asleep and wishing the black mare would get out of the water trough before things went south.

The last fourteen years of Nettie’s life had passed in a shriveled corner of Durango territory under the leaking roof of this wind-chapped lean-to with Pap and Mam, not quite a slave and nowhere close to something like a daughter. Their faces, white and wobbling as new butter under a smear of prairie dirt, held no kindness. The boots and the mule had belonged to Pap, right up until the day he’d exhausted their use, a sentiment he threatened to apply to her every time she was just a little too slow with the porridge.

“Nettie! Girl, you take care of that wild filly, or I’ll put one in her goddamn skull!”

Pap got in a lather when he’d been drinking, which was pretty much always. At least this time his anger was aimed at a critter instead of Nettie. When the witch-hearted black filly had first shown up on the farm, Pap had laid claim and pronounced her a fine chunk of flesh and a sign of the Creator’s good graces. If Nettie broke her and sold her for a decent price, she’d be closer to paying back Pap for taking her in as a baby when nobody else had wanted her but the hungry, circling vultures. The value Pap placed on feeding and housing a half-Injun, half-black orphan girl always seemed to go up instead of down, no matter that Nettie did most of the work around the homestead these days. Maybe that was why she’d not been taught her sums: Then she’d know her own damn worth, to the penny.

But the dainty black mare outside wouldn’t be roped, much less saddled and gentled, and Nettie had failed to sell her to the cowpokes at the Double TK Ranch next door. Her idol, Monty, was a top hand and always had a kind word. But even he had put a boot on Pap’s poorly kept fence, laughed through his mustache, and hollered that a horse that couldn’t be caught couldn’t be sold. No matter how many times Pap drove the filly away with poorly thrown bottles, stones, and bullets, the critter crept back under cover of night to ruin the water by dancing a jig in the trough, which meant another blistering trip to the creek with a leaky bucket for Nettie.

Splash, splash. Whinny.

Could a horse laugh? Nettie figured this one could.

Pap, however, was a humorless bastard who didn’t get a joke that didn’t involve bruises.

“Unless you wanna go live in the flats, eatin’ bugs, you’d best get on, girl.”

Nettie rolled off her worn-out straw tick, hoping there weren’t any scorpions or centipedes on the dusty dirt floor. By the moon’s scant light she shook out Pap’s old boots and shoved her bare feet into into the cracked leather.

Splash, splash.

The shotgun cocked loud enough to be heard across the border, and Nettie dove into Mam’s old wool cloak and ran toward the stockyard with her long, thick braids slapping against her back. Mam said nothing, just rocked in her chair by the window, a bottle cradled in her arm like a baby’s corpse. Grabbing the rawhide whip from its nail by the warped door, Nettie hurried past Pap on the porch and stumbled across the yard, around two mostly roofless barns, and toward the wet black shape taunting her in the moonlight against a backdrop of stars.

“Get on, mare. Go!”

A monster in a flapping jacket with a waving whip would send any horse with sense wheeling in the opposite direction, but this horse had apparently been dancing in the creek on the day sense was handed out. The mare stood in the water trough and stared at Nettie like she was a damn strange bird, her dark eyes blinking with moonlight and her lips pulled back over long, white teeth.

Nettie slowed. She wasn’t one to quirt a horse, but if the mare kept causing a ruckus, Pap would shoot her without a second or even a first thought—and he wasn’t so deep in his bottle that he was sure to miss. Getting smacked with rawhide had to be better than getting shot in the head, so Nettie doubled up her shouting and prepared herself for the heartache that would accompany the smack of a whip on unmarred hide. She didn’t even own the horse, much less the right to beat it. Nettie had grown up trying to be the opposite of Pap, and hurting something that didn’t come with claws and a stinger went against her grain.

“Shoo, fool, or I’ll have to whip you,” she said, creeping closer. The horse didn’t budge, and for the millionth time, Nettie swung the whip around the horse’s neck like a rope, all gentle-like. But, as ever, the mare tossed her head at exactly the right moment, and the braided leather snickered against the wooden water trough instead.

“Godamighty, why won’t you move on? Ain’t nobody wants you, if you won’t be rode or bred. Dumb mare.”

At that, the horse reared up with a wild scream, spraying water as she pawed the air. Before Nettie could leap back to avoid the splatter, the mare had wheeled and galloped into the night. The starlight showed her streaking across the prairie with a speed Nettie herself would’ve enjoyed, especially if it meant she could turn her back on Pap’s dirt-poor farm and no-good cattle company forever. Doubling over to stare at her scuffed boots while she caught her breath, Nettie felt her hope disappear with hoofbeats in the night.

A low and painfully unfamiliar laugh trembled out of the barn’s shadow, and Nettie cocked the whip back so that it was ready to strike.

“Who’s that? Jed?”

But it wasn’t Jed, the mule-kicked, sometimes stable boy, and she already knew it.

“Looks like that black mare’s giving you a spot of trouble, darlin’. If you were smart, you’d set fire to her tail.”

A figure peeled away from the barn, jerky-thin and slithery in a too-short coat with buttons that glinted like extra stars. The man’s hat was pulled low, his brown hair overshaggy and his lily-white hand on his gun in a manner both unfriendly and relaxed that Nettie found insulting.

“You best run off, mister. Pap don’t like strangers on his land, especially when he’s only a bottle in. If it’s horses you want, we ain’t got none worth selling. If you want work and you’re dumb and blind, best come back in the morning when he’s slept off the mezcal.”

“I wouldn’t work for that good-for-nothing piss-pot even if I needed work.”

The stranger switched sides with his toothpick and looked Nettie up and down like a horse he was thinking about stealing. Her fist tightened on the whip handle, her fingers going cold. She wouldn’t defend Pap or his land or his sorry excuses for cattle, but she’d defend the only thing other than Blue that mostly belonged to her. Men had been pawing at her for two years now, and nobody’d yet come close to reaching her soft parts, not even Pap.

“Then you’d best move on, mister.”

The feller spit his toothpick out on the ground and took a step forward, all quiet-like because he wore no spurs. And that was Nettie’s first clue that he wasn’t what he seemed.

“Naw, I’ll stay. Pretty little thing like you to keep me company.”

That was Nettie’s second clue. Nobody called her pretty unless they wanted something. She looked around the yard, but all she saw were sand, chaparral, bone-dry cow patties, and the remains of a fence that Pap hadn’t seen fit to fix. Mam was surely asleep, and Pap had gone inside, or maybe around back to piss. It was just the stranger and her. And the whip.

“Bullshit,” she spit.

“Put down that whip before you hurt yourself, girl.”

“Don’t reckon I will.”

The stranger stroked his pistol and started to circle her. Nettie shook the whip out behind her as she spun in place to face him and hunched over in a crouch. He stopped circling when the barn yawned behind her, barely a shell of a thing but darker than sin in the corners. And then he took a step forward, his silver pistol out and flashing starlight. Against her will, she took a step back. Inch by inch he drove her into the barn with slow, easy steps. Her feet rattled in the big boots, her fingers numb around the whip she had forgotten how to use.

“What is it you think you’re gonna do to me, mister?”

It came out breathless, god damn her tongue.

His mouth turned up like a cat in the sun. “Something nice. Something somebody probably done to you already. Your master or pappy, maybe.”

She pushed air out through her nose like a bull. “Ain’t got a pappy. Or a master.”

“Then I guess nobody’ll mind, will they?”

That was pretty much it for Nettie Lonesome. She spun on her heel and ran into the barn, right where he’d been pushing her to go. But she didn’t flop down on the hay or toss down the mangy blanket that had dried into folds in the broke-down, three-wheeled rig. No, she snatched the sickle from the wall and spun to face him under the hole in the roof. Starlight fell down on her ink-black braids and glinted off the parts of the curved blade that weren’t rusted up.

“I reckon I’d mind,” she said.

Nettie wasn’t a little thing, at least not height-wise, and she’d figured that seeing a pissed-off woman with a weapon in each hand would be enough to drive off the curious feller and send him back to the whores at the Leaping Lizard, where he apparently belonged. But the stranger just laughed and cracked his knuckles like he was glad for a fight and would take his pleasure with his fists instead of his twig.

“You wanna play first? Go on, girl. Have your fun. You think you’re facin’ down a coydog, but you found a timber wolf.”

As he stepped into the barn, the stranger went into shadow for just a second, and that was when Nettie struck. Her whip whistled for his feet and managed to catch one ankle, yanking hard enough to pluck him off his feet and onto the back of his fancy jacket. A puff of dust went up as he thumped on the ground, but he just crossed his ankles and stared at her and laughed. Which pissed her off more. Dropping the whip handle, Nettie took the sickle in both hands and went for the stranger’s legs, hoping that a good slash would keep him from chasing her but not get her sent to the hangman’s noose. But her blade whistled over a patch of nothing. The man was gone, her whip with him.

Nettie stepped into the doorway to watch him run away, her heart thumping underneath the tight muslin binding she always wore over her chest. She squinted into the long, flat night, one hand on the hinge of what used to be a barn door, back before the church was willing to pay cash money for Pap’s old lumber. But the stranger wasn’t hightailing it across the prairie. Which meant…

“Looking for someone, darlin’?”

She spun, sickle in hand, and sliced into something that felt like a ham with the round part of the blade. Hot blood spattered over her, burning like lye.

“Goddammit, girl! What’d you do that for?”

She ripped the sickle out with a sick splash, but the man wasn’t standing in the barn, much less falling to the floor. He was hanging upside-down from a cross-beam, cradling his arm. It made no goddamn sense, and Nettie couldn’t stand a thing that made no sense, so she struck again while he was poking around his wound.

This time, she caught him in the neck. This time, he fell.

The stranger landed in the dirt and popped right back up into a crouch. The slice in his neck looked like the first carving in an undercooked roast, but the blood was slurry and smelled like rotten meat. And the stranger was sneering at her.

“Girl, you just made the biggest mistake of your short, useless life.”

Then he sprang at her.

There was no way he should’ve been able to jump at her like that with those wounds, and she brought her hands straight up without thinking. Luckily, her fist still held the sickle, and the stranger took it right in the face, the point of the blade jerking into his eyeball with a moist squish. Nettie turned away and lost most of last night’s meager dinner in a noisy splatter against the wall of the barn. When she spun back around, she was surprised to find that the fool hadn’t fallen or died or done anything helpful to her cause. Without a word, he calmly pulled the blade out of his eye and wiped a dribble of black glop off his cheek.

His smile was a cold, dark thing that sent Nettie’s feet toward Pap and the crooked house and anything but the stranger who wouldn’t die, wouldn’t scream, and wouldn’t leave her alone. She’d never felt safe a day in her life, but now she recognized the chill hand of death, reaching for her. Her feet trembled in the too-big boots as she stumbled backward across the bumpy yard, tripping on stones and bits of trash. Turning her back on the demon man seemed intolerably stupid. She just had to get past the round pen, and then she’d be halfway to the house. Pap wouldn’t be worth much by now, but he had a gun by his side. Maybe the stranger would give up if he saw a man instead of just a half-breed girl nobody cared about.

Nettie turned to run and tripped on a fallen chunk of fence, going down hard on hands and skinned knees. When she looked up, she saw butternut-brown pants stippled with blood and no-spur boots tapping.

“Pap!” she shouted. “Pap, help!”

She was gulping in a big breath to holler again when the stranger’s boot caught her right under the ribs and knocked it all back out. The force of the kick flipped her over onto her back, and she scrabbled away from the stranger and toward the ramshackle round pen of old, gray branches and junk roped together, just barely enough fence to trick a colt into staying put. They’d slaughtered a pig in here, once, and now Nettie knew how he felt.

As soon as her back fetched up against the pen, the stranger crouched in front of her, one eye closed and weeping black and the other brim-full with evil over the bloody slice in his neck. He looked like a dead man, a corpse groom, and Nettie was pretty sure she was in the hell Mam kept threatening her with.

“Ain’t nobody coming. Ain’t nobody cares about a girl like you. Ain’t nobody gonna need to, not after what you done to me.”

The stranger leaned down and made like he was going to kiss her with his mouth wide open, and Nettie did the only thing that came to mind. She grabbed up a stout twig from the wall of the pen and stabbed him in the chest as hard as she damn could.

She expected the stick to break against his shirt like the time she’d seen a buggy bash apart against the general store during a twister. But the twig sunk right in like a hot knife in butter. The stranger shuddered and fell on her, his mouth working as gloppy red-black liquid bubbled out. She didn’t trust blood anymore, not after the first splat had burned her, and she wasn’t much for being found under a corpse, so Nettie shoved him off hard and shot to her feet, blowing air as hard as a galloping horse.

The stranger was rolling around on the ground, plucking at his chest. Thick clouds blotted out the meager starlight, and she had nothing like the view she’d have tomorrow under the white-hot, unrelenting sun. But even a girl who’d never killed a man before knew when something was wrong. She kicked him over with the toe of her boot, tit for tat, and he was light as a tumbleweed when he landed on his back.

The twig jutted up out of a black splotch in his shirt, and the slice in his neck had curled over like gone meat. His bad eye was a swamp of black, but then, everything was black at midnight. His mouth was open, the lips drawing back over too-white teeth, several of which looked like they’d come out of a panther. He wasn’t breathing, and Pap wasn’t coming, and Nettie’s finger reached out as if it had a mind of its own and flicked one big, shiny, curved tooth.

The goddamn thing fell back into the dead man’s gaping throat. Nettie jumped away, skitty as the black filly, and her boot toe brushed the dead man’s shoulder, and his entire body collapsed in on itself like a puffball, thousands of sparkly motes piling up in the place he’d occupied and spilling out through his empty clothes. Utterly bewildered, she knelt and brushed the pile with trembling fingers. It was sand. Nothing but sand. A soft wind came up just then and blew some of the stranger away, revealing one of those big, curved teeth where his head had been. It didn’t make a goddamn lick of sense, but it could’ve gone far worse.

Still wary, she stood and shook out his clothes, noting that everything was in better than fine condition, except for his white shirt, which had a twig-sized hole in the breast, surrounded by a smear of black. She knew enough of laundering and sewing to make it nice enough, and the black blood on his pants looked, to her eye, manly and tough. Even the stranger’s boots were of better quality than any that had ever set foot on Pap’s land, snakeskin with fancy chasing. With her own, too-big boots, she smeared the sand back into the hard, dry ground as if the stranger had never existed. All that was left was the four big panther teeth, and she put those in her pocket and tried to forget about them.

After checking the yard for anything livelier than a scorpion, she rolled up the clothes around the boots and hid them in the old rig in the barn. Knowing Pap would pester her if she left signs of a scuffle, she wiped the black glop off the sickle and hung it up, along with the whip, out of Pap’s drunken reach. She didn’t need any more whip scars on her back than she already had.

Out by the round pen, the sand that had once been a devil of a stranger had all blown away. There was no sign of what had almost happened, just a few more deadwood twigs pulled from the lopsided fence. On good days, Nettie spent a fair bit of time doing the dangerous work of breaking colts or doctoring cattle in here for Pap, then picking up the twigs that got knocked off and roping them back in with whatever twine she could scavenge from the town. Wood wasn’t cheap, and there wasn’t much of it. But Nettie’s hands were twitchy still, and so she picked up the black-splattered stick and wove it back into the fence, wishing she lived in a world where her life was worth more than a mule, more than boots, more than a stranger’s cold smile in the barn. She’d had her first victory, but no one would ever believe her, and if they did, she wouldn’t be cheered. She’d be hanged.

That stranger—he had been all kinds of wrong. And the way that he’d wanted to touch her—that felt wrong, too. Nettie couldn’t recall being touched in kindness, not in all her years with Pap and Mam. Maybe that was why she understood horses. Mustangs were wild things captured by thoughtless men, roped and branded and beaten until their heads hung low, until it took spurs and whips to move them in rage and fear. But Nettie could feel the wildness inside their hearts, beating under skin that quivered under the flat of her palm. She didn’t break a horse, she gentled it. And until someone touched her with that same kindness, she would continue to shy away, to bare her teeth and lower her head.

Someone, surely, had been kind to her once, long ago. She could feel it in her bones. But Pap said she’d been tossed out like trash, left on the prairie to die. Which she almost had, tonight. Again.

Pap and Mam were asleep on the porch, snoring loud as thunder. When Nettie crept past them and into the house, she had four shiny teeth in one fist, a wad of cash from the stranger’s pocket, and more questions than there were stars.

Nettie barely slept a wink that night. Every time her eyes blinked shut, she imagined the stranger pulling himself together, the sand shifting back into the shape of something like a man and slithering into the house past Pap sleeping on the porch. One eye dripping black, he’d rise up like a rattler, snatch his teeth from inside her boot, poke them back into his gums, and rip her throat out.

After the third time she jolted up with a fright, alone in the dark with a stick-knife in her fist, she figured to hell with it and just got on up. Despite the drenching Durango heat, she’d taken to dressing like a bandito’s grandmother with one of Pap’s old, faded shirts over her bound chest, baggy pants held up by a rope, and a moth-gnawed serape over that. The less the folks of Gloomy Bluebird could see she was a girl, the less trouble they gave her.

Mam and Pap had taken to sending her on all their errands into town, considering they owed so many debts. Nettie’d learned that if she kept her head down and sucked in her cheeks, folks usually took pity and gave her the tail end of a sack of cornmeal or their most pitiful, nonlaying chicken. At first, she’d been embarrassed. But then she’d overheard two of the old biddy church ladies whispering about how shameful it was for Pap to send his half-breed slave pup around to beg, and she realized that they counted her for less than a dog and Pap only slightly more than that.

Mam and Pap Lonesome were of old East stock, pale as salt fish and just as odorous, with matching hay-colored hair and blue eyes that seemed ever confused thanks to eyelashes and eyebrows as light as dandelion fuzz. The pair were shapeless and old enough to look like someone else’s aunt. Nettie couldn’t have been more different, with medium brown skin that could’ve been called liver chestnut, if she’d been a horse worth noticing. Her hair was thick and frizzy, a dead giveaway to anyone trying to puzzle out her breed. Half black and half Injun, or maybe Aztecan; any way you added it up, the end result was somehow less than the individual components. She was built tall and narrow like a half-starved antelope, with eyes as dark and thick as a storm-mad creek and high cheekbones framing a mouth that had little reason to smile. She was ugly, was all they’d told her. But she didn’t find them beautiful, so what did it matter? The entire town was an eyesore.

It was widely agreed that Gloomy Bluebird was a stupid name for a town, especially considering Old Ollie Hampstead had shot the only bluebird they had back in 1822, right outside what passed as a general store. The damn thing had been stuffed and posed with little skill and now sat proudly on the storekeeper’s counter as a reminder of what looking cheerful and bright would get you in a town as dusty as an old maid’s britches. Nettie herself had seen a bluebird when she was just a little thing, hunting lizards out by the creek. When she’d run home to tell Mam, she’d been told to go fetch a switch for lying. Over time, she’d come to believe she must’ve seen a crow. But crows didn’t have red bellies, did they? At least the town lived up to the gloomy part.

The excitement of last night had burned off, and Nettie was feeling downright gloomy herself, like some part of her had blown away with the impossible, sparkling sand. A strange thing had happened, and she had no one to tell, no one she trusted enough to question. Being alone wasn’t so bad when nothing ever changed, but now Nettie didn’t trust herself, and she was generally the only person she could trust.

Although Pap handled most of her punishment, Mam had once thrashed her for lying about a bluebird, and then thrashed her again when she’d started her monthlies and ruined an old striped mattress and screamed that she was dying. How was she supposed to know that was what women did? Nettie didn’t reckon much about the world, but she knew that what happened last night had changed things as much as her flux blood. The world was suddenly more dangerous, but she had no idea why or how to protect herself from it. Seemed like the best way to keep her skin was to get on with breakfast and not say a danged thing, to hide it like she hid everything else.

When she went to shake her boots for scorpions, it was four pointed teeth that fell out. Considering no crevice of the shack was safe from Mam’s quick fingers, Nettie shoved them into the little leather bag she kept tied around her waist with what few precious things she’d found over the years. A glittery white arrowhead, hardly chipped. A shiny gold button with a bugle on it. A wolf claw, or something like it. A penny given to her once in the town when she’d been kicked in the leg by a frachetty horse. She’d kept a piece of dirt-dusted ribbon candy some town brat had dropped in the pouch for two weeks once, allowing herself one suck a day. The four teeth added a weight barely felt, but she stood a mite taller. Whatever that stranger had been, she’d won. And that felt pretty goddamn good.

Mam and Pap weren’t up, of course. They gave the sun time to stretch and get cozy before they stopped snoring. It was almost peaceful, setting up the porridge in the pot and watching the skillet shimmer with fatback grease. She always loved snatching warm eggs from under the scrawny, sleepy hens; this brood was the result of Pap’s once-a-year victory at the poker table. They’d definitely seen harder times, although Nettie didn’t much get to enjoy the bounty herself. If Mam and Pap left any eggs on their plates, that was usually treat enough.

The sun came up so fast that if you weren’t watching careful, you’d miss it. For just a second, it was a flat circle, hot-red and bleeding all over the soft, purple clouds. Nettie stared at it as long as she could, not blinking, then leaned over to turn the eggs, and when she looked again, the sun sat high and white, relentlessly beating down on the endless prairie. Sunset, at least, took its time, nice and lazy. She liked the colors of it, and the way that no one could own the sun. It couldn’t be compelled, couldn’t be roped. You could yell at it all day long, threaten and plead and cuss, and the sun would not budge a goddamn inch. It was what it was, and it took its damn time about it.

But Nettie had fewer choices, so she quickly bolted down her small share of the porridge. Not only because Mam and Pap would give her an earful if they woke up with her in the house, but also because she wanted to mosey over to the Double TK before the surlier of the cowboys were awake and taking out their hangovers on whoever happened by. The ranch next door was far richer than Pap’s, considering they had more than a one-eyed mule, two nags for renting, a herd of cattle too thin for the butcher to carve, and one milk cow that barely squirted enough milk for weak porridge. Mam had sent her toddling over to the Double TK for the first time to have a knife sharpened when she was just five years old, and Monty had taken her on like a lost pup. The old cowpoke had told her, years later, that they’d figured her for a boy at first, as she’d been in britches and had a shorn head. But since she’d been mannerly and offered to help the wranglers by sweeping out the pen or tossing rocks at vultures, they’d generally tolerated her presence.

Over the years, she’d learned by watching Monty and had figured out better ways to work a colt than using Pap’s whip. She was awful shy of the other cowpokes and never went near the ranch house or Boss Kimble, but Monty said he was right glad for her calm hand with the horses and general quietude. He was still thin and tough as leather, with a luxurious mustache, but she’d noticed that in the last couple of years, Monty had saved the wilder horses for her visits and chosen gentler mounts for himself, and that his mustache had gone to gray.

On her way to the Double TK, she stopped to feed the few critters Pap hadn’t used up yet. Blue greeted her with his usual hollering, and she gave him a once-over and a fine scratch and fed him a precious handful of grain, plus a bite she’d held back from the porridge. He pressed his big, ugly mule nose over her shoulder, and she leaned into his skinny chest and breathed in his good horse smell. He didn’t know he wasn’t a horse, and he didn’t know he was ugly. Pap’s swayback mare, Fussy, took the grain and turned her tail, just as sour as her owner, and the aged nag they called Dusty refused to get up off the ground. The wild black mare was still gone and the water trough still clean, thank heavens. Nettie had already fed the cow and scattered the morning’s corn for the chickens, but the poor things crowded around her with hopeful clucking. It was a sad joke, calling it a ranch.

Before heading off, Nettie snuck into the other barn to see if the stranger’s clothes were . . .

The last fourteen years of Nettie’s life had passed in a shriveled corner of Durango territory under the leaking roof of this wind-chapped lean-to with Pap and Mam, not quite a slave and nowhere close to something like a daughter. Their faces, white and wobbling as new butter under a smear of prairie dirt, held no kindness. The boots and the mule had belonged to Pap, right up until the day he’d exhausted their use, a sentiment he threatened to apply to her every time she was just a little too slow with the porridge.

“Nettie! Girl, you take care of that wild filly, or I’ll put one in her goddamn skull!”

Pap got in a lather when he’d been drinking, which was pretty much always. At least this time his anger was aimed at a critter instead of Nettie. When the witch-hearted black filly had first shown up on the farm, Pap had laid claim and pronounced her a fine chunk of flesh and a sign of the Creator’s good graces. If Nettie broke her and sold her for a decent price, she’d be closer to paying back Pap for taking her in as a baby when nobody else had wanted her but the hungry, circling vultures. The value Pap placed on feeding and housing a half-Injun, half-black orphan girl always seemed to go up instead of down, no matter that Nettie did most of the work around the homestead these days. Maybe that was why she’d not been taught her sums: Then she’d know her own damn worth, to the penny.

But the dainty black mare outside wouldn’t be roped, much less saddled and gentled, and Nettie had failed to sell her to the cowpokes at the Double TK Ranch next door. Her idol, Monty, was a top hand and always had a kind word. But even he had put a boot on Pap’s poorly kept fence, laughed through his mustache, and hollered that a horse that couldn’t be caught couldn’t be sold. No matter how many times Pap drove the filly away with poorly thrown bottles, stones, and bullets, the critter crept back under cover of night to ruin the water by dancing a jig in the trough, which meant another blistering trip to the creek with a leaky bucket for Nettie.

Splash, splash. Whinny.

Could a horse laugh? Nettie figured this one could.

Pap, however, was a humorless bastard who didn’t get a joke that didn’t involve bruises.

“Unless you wanna go live in the flats, eatin’ bugs, you’d best get on, girl.”

Nettie rolled off her worn-out straw tick, hoping there weren’t any scorpions or centipedes on the dusty dirt floor. By the moon’s scant light she shook out Pap’s old boots and shoved her bare feet into into the cracked leather.

Splash, splash.

The shotgun cocked loud enough to be heard across the border, and Nettie dove into Mam’s old wool cloak and ran toward the stockyard with her long, thick braids slapping against her back. Mam said nothing, just rocked in her chair by the window, a bottle cradled in her arm like a baby’s corpse. Grabbing the rawhide whip from its nail by the warped door, Nettie hurried past Pap on the porch and stumbled across the yard, around two mostly roofless barns, and toward the wet black shape taunting her in the moonlight against a backdrop of stars.

“Get on, mare. Go!”

A monster in a flapping jacket with a waving whip would send any horse with sense wheeling in the opposite direction, but this horse had apparently been dancing in the creek on the day sense was handed out. The mare stood in the water trough and stared at Nettie like she was a damn strange bird, her dark eyes blinking with moonlight and her lips pulled back over long, white teeth.

Nettie slowed. She wasn’t one to quirt a horse, but if the mare kept causing a ruckus, Pap would shoot her without a second or even a first thought—and he wasn’t so deep in his bottle that he was sure to miss. Getting smacked with rawhide had to be better than getting shot in the head, so Nettie doubled up her shouting and prepared herself for the heartache that would accompany the smack of a whip on unmarred hide. She didn’t even own the horse, much less the right to beat it. Nettie had grown up trying to be the opposite of Pap, and hurting something that didn’t come with claws and a stinger went against her grain.

“Shoo, fool, or I’ll have to whip you,” she said, creeping closer. The horse didn’t budge, and for the millionth time, Nettie swung the whip around the horse’s neck like a rope, all gentle-like. But, as ever, the mare tossed her head at exactly the right moment, and the braided leather snickered against the wooden water trough instead.

“Godamighty, why won’t you move on? Ain’t nobody wants you, if you won’t be rode or bred. Dumb mare.”

At that, the horse reared up with a wild scream, spraying water as she pawed the air. Before Nettie could leap back to avoid the splatter, the mare had wheeled and galloped into the night. The starlight showed her streaking across the prairie with a speed Nettie herself would’ve enjoyed, especially if it meant she could turn her back on Pap’s dirt-poor farm and no-good cattle company forever. Doubling over to stare at her scuffed boots while she caught her breath, Nettie felt her hope disappear with hoofbeats in the night.

A low and painfully unfamiliar laugh trembled out of the barn’s shadow, and Nettie cocked the whip back so that it was ready to strike.

“Who’s that? Jed?”

But it wasn’t Jed, the mule-kicked, sometimes stable boy, and she already knew it.

“Looks like that black mare’s giving you a spot of trouble, darlin’. If you were smart, you’d set fire to her tail.”

A figure peeled away from the barn, jerky-thin and slithery in a too-short coat with buttons that glinted like extra stars. The man’s hat was pulled low, his brown hair overshaggy and his lily-white hand on his gun in a manner both unfriendly and relaxed that Nettie found insulting.

“You best run off, mister. Pap don’t like strangers on his land, especially when he’s only a bottle in. If it’s horses you want, we ain’t got none worth selling. If you want work and you’re dumb and blind, best come back in the morning when he’s slept off the mezcal.”

“I wouldn’t work for that good-for-nothing piss-pot even if I needed work.”

The stranger switched sides with his toothpick and looked Nettie up and down like a horse he was thinking about stealing. Her fist tightened on the whip handle, her fingers going cold. She wouldn’t defend Pap or his land or his sorry excuses for cattle, but she’d defend the only thing other than Blue that mostly belonged to her. Men had been pawing at her for two years now, and nobody’d yet come close to reaching her soft parts, not even Pap.

“Then you’d best move on, mister.”

The feller spit his toothpick out on the ground and took a step forward, all quiet-like because he wore no spurs. And that was Nettie’s first clue that he wasn’t what he seemed.

“Naw, I’ll stay. Pretty little thing like you to keep me company.”

That was Nettie’s second clue. Nobody called her pretty unless they wanted something. She looked around the yard, but all she saw were sand, chaparral, bone-dry cow patties, and the remains of a fence that Pap hadn’t seen fit to fix. Mam was surely asleep, and Pap had gone inside, or maybe around back to piss. It was just the stranger and her. And the whip.

“Bullshit,” she spit.

“Put down that whip before you hurt yourself, girl.”

“Don’t reckon I will.”

The stranger stroked his pistol and started to circle her. Nettie shook the whip out behind her as she spun in place to face him and hunched over in a crouch. He stopped circling when the barn yawned behind her, barely a shell of a thing but darker than sin in the corners. And then he took a step forward, his silver pistol out and flashing starlight. Against her will, she took a step back. Inch by inch he drove her into the barn with slow, easy steps. Her feet rattled in the big boots, her fingers numb around the whip she had forgotten how to use.

“What is it you think you’re gonna do to me, mister?”

It came out breathless, god damn her tongue.

His mouth turned up like a cat in the sun. “Something nice. Something somebody probably done to you already. Your master or pappy, maybe.”

She pushed air out through her nose like a bull. “Ain’t got a pappy. Or a master.”

“Then I guess nobody’ll mind, will they?”

That was pretty much it for Nettie Lonesome. She spun on her heel and ran into the barn, right where he’d been pushing her to go. But she didn’t flop down on the hay or toss down the mangy blanket that had dried into folds in the broke-down, three-wheeled rig. No, she snatched the sickle from the wall and spun to face him under the hole in the roof. Starlight fell down on her ink-black braids and glinted off the parts of the curved blade that weren’t rusted up.

“I reckon I’d mind,” she said.

Nettie wasn’t a little thing, at least not height-wise, and she’d figured that seeing a pissed-off woman with a weapon in each hand would be enough to drive off the curious feller and send him back to the whores at the Leaping Lizard, where he apparently belonged. But the stranger just laughed and cracked his knuckles like he was glad for a fight and would take his pleasure with his fists instead of his twig.

“You wanna play first? Go on, girl. Have your fun. You think you’re facin’ down a coydog, but you found a timber wolf.”

As he stepped into the barn, the stranger went into shadow for just a second, and that was when Nettie struck. Her whip whistled for his feet and managed to catch one ankle, yanking hard enough to pluck him off his feet and onto the back of his fancy jacket. A puff of dust went up as he thumped on the ground, but he just crossed his ankles and stared at her and laughed. Which pissed her off more. Dropping the whip handle, Nettie took the sickle in both hands and went for the stranger’s legs, hoping that a good slash would keep him from chasing her but not get her sent to the hangman’s noose. But her blade whistled over a patch of nothing. The man was gone, her whip with him.

Nettie stepped into the doorway to watch him run away, her heart thumping underneath the tight muslin binding she always wore over her chest. She squinted into the long, flat night, one hand on the hinge of what used to be a barn door, back before the church was willing to pay cash money for Pap’s old lumber. But the stranger wasn’t hightailing it across the prairie. Which meant…

“Looking for someone, darlin’?”

She spun, sickle in hand, and sliced into something that felt like a ham with the round part of the blade. Hot blood spattered over her, burning like lye.

“Goddammit, girl! What’d you do that for?”

She ripped the sickle out with a sick splash, but the man wasn’t standing in the barn, much less falling to the floor. He was hanging upside-down from a cross-beam, cradling his arm. It made no goddamn sense, and Nettie couldn’t stand a thing that made no sense, so she struck again while he was poking around his wound.

This time, she caught him in the neck. This time, he fell.

The stranger landed in the dirt and popped right back up into a crouch. The slice in his neck looked like the first carving in an undercooked roast, but the blood was slurry and smelled like rotten meat. And the stranger was sneering at her.

“Girl, you just made the biggest mistake of your short, useless life.”

Then he sprang at her.

There was no way he should’ve been able to jump at her like that with those wounds, and she brought her hands straight up without thinking. Luckily, her fist still held the sickle, and the stranger took it right in the face, the point of the blade jerking into his eyeball with a moist squish. Nettie turned away and lost most of last night’s meager dinner in a noisy splatter against the wall of the barn. When she spun back around, she was surprised to find that the fool hadn’t fallen or died or done anything helpful to her cause. Without a word, he calmly pulled the blade out of his eye and wiped a dribble of black glop off his cheek.

His smile was a cold, dark thing that sent Nettie’s feet toward Pap and the crooked house and anything but the stranger who wouldn’t die, wouldn’t scream, and wouldn’t leave her alone. She’d never felt safe a day in her life, but now she recognized the chill hand of death, reaching for her. Her feet trembled in the too-big boots as she stumbled backward across the bumpy yard, tripping on stones and bits of trash. Turning her back on the demon man seemed intolerably stupid. She just had to get past the round pen, and then she’d be halfway to the house. Pap wouldn’t be worth much by now, but he had a gun by his side. Maybe the stranger would give up if he saw a man instead of just a half-breed girl nobody cared about.

Nettie turned to run and tripped on a fallen chunk of fence, going down hard on hands and skinned knees. When she looked up, she saw butternut-brown pants stippled with blood and no-spur boots tapping.

“Pap!” she shouted. “Pap, help!”

She was gulping in a big breath to holler again when the stranger’s boot caught her right under the ribs and knocked it all back out. The force of the kick flipped her over onto her back, and she scrabbled away from the stranger and toward the ramshackle round pen of old, gray branches and junk roped together, just barely enough fence to trick a colt into staying put. They’d slaughtered a pig in here, once, and now Nettie knew how he felt.

As soon as her back fetched up against the pen, the stranger crouched in front of her, one eye closed and weeping black and the other brim-full with evil over the bloody slice in his neck. He looked like a dead man, a corpse groom, and Nettie was pretty sure she was in the hell Mam kept threatening her with.

“Ain’t nobody coming. Ain’t nobody cares about a girl like you. Ain’t nobody gonna need to, not after what you done to me.”

The stranger leaned down and made like he was going to kiss her with his mouth wide open, and Nettie did the only thing that came to mind. She grabbed up a stout twig from the wall of the pen and stabbed him in the chest as hard as she damn could.

She expected the stick to break against his shirt like the time she’d seen a buggy bash apart against the general store during a twister. But the twig sunk right in like a hot knife in butter. The stranger shuddered and fell on her, his mouth working as gloppy red-black liquid bubbled out. She didn’t trust blood anymore, not after the first splat had burned her, and she wasn’t much for being found under a corpse, so Nettie shoved him off hard and shot to her feet, blowing air as hard as a galloping horse.

The stranger was rolling around on the ground, plucking at his chest. Thick clouds blotted out the meager starlight, and she had nothing like the view she’d have tomorrow under the white-hot, unrelenting sun. But even a girl who’d never killed a man before knew when something was wrong. She kicked him over with the toe of her boot, tit for tat, and he was light as a tumbleweed when he landed on his back.

The twig jutted up out of a black splotch in his shirt, and the slice in his neck had curled over like gone meat. His bad eye was a swamp of black, but then, everything was black at midnight. His mouth was open, the lips drawing back over too-white teeth, several of which looked like they’d come out of a panther. He wasn’t breathing, and Pap wasn’t coming, and Nettie’s finger reached out as if it had a mind of its own and flicked one big, shiny, curved tooth.

The goddamn thing fell back into the dead man’s gaping throat. Nettie jumped away, skitty as the black filly, and her boot toe brushed the dead man’s shoulder, and his entire body collapsed in on itself like a puffball, thousands of sparkly motes piling up in the place he’d occupied and spilling out through his empty clothes. Utterly bewildered, she knelt and brushed the pile with trembling fingers. It was sand. Nothing but sand. A soft wind came up just then and blew some of the stranger away, revealing one of those big, curved teeth where his head had been. It didn’t make a goddamn lick of sense, but it could’ve gone far worse.

Still wary, she stood and shook out his clothes, noting that everything was in better than fine condition, except for his white shirt, which had a twig-sized hole in the breast, surrounded by a smear of black. She knew enough of laundering and sewing to make it nice enough, and the black blood on his pants looked, to her eye, manly and tough. Even the stranger’s boots were of better quality than any that had ever set foot on Pap’s land, snakeskin with fancy chasing. With her own, too-big boots, she smeared the sand back into the hard, dry ground as if the stranger had never existed. All that was left was the four big panther teeth, and she put those in her pocket and tried to forget about them.

After checking the yard for anything livelier than a scorpion, she rolled up the clothes around the boots and hid them in the old rig in the barn. Knowing Pap would pester her if she left signs of a scuffle, she wiped the black glop off the sickle and hung it up, along with the whip, out of Pap’s drunken reach. She didn’t need any more whip scars on her back than she already had.

Out by the round pen, the sand that had once been a devil of a stranger had all blown away. There was no sign of what had almost happened, just a few more deadwood twigs pulled from the lopsided fence. On good days, Nettie spent a fair bit of time doing the dangerous work of breaking colts or doctoring cattle in here for Pap, then picking up the twigs that got knocked off and roping them back in with whatever twine she could scavenge from the town. Wood wasn’t cheap, and there wasn’t much of it. But Nettie’s hands were twitchy still, and so she picked up the black-splattered stick and wove it back into the fence, wishing she lived in a world where her life was worth more than a mule, more than boots, more than a stranger’s cold smile in the barn. She’d had her first victory, but no one would ever believe her, and if they did, she wouldn’t be cheered. She’d be hanged.

That stranger—he had been all kinds of wrong. And the way that he’d wanted to touch her—that felt wrong, too. Nettie couldn’t recall being touched in kindness, not in all her years with Pap and Mam. Maybe that was why she understood horses. Mustangs were wild things captured by thoughtless men, roped and branded and beaten until their heads hung low, until it took spurs and whips to move them in rage and fear. But Nettie could feel the wildness inside their hearts, beating under skin that quivered under the flat of her palm. She didn’t break a horse, she gentled it. And until someone touched her with that same kindness, she would continue to shy away, to bare her teeth and lower her head.

Someone, surely, had been kind to her once, long ago. She could feel it in her bones. But Pap said she’d been tossed out like trash, left on the prairie to die. Which she almost had, tonight. Again.

Pap and Mam were asleep on the porch, snoring loud as thunder. When Nettie crept past them and into the house, she had four shiny teeth in one fist, a wad of cash from the stranger’s pocket, and more questions than there were stars.

Nettie barely slept a wink that night. Every time her eyes blinked shut, she imagined the stranger pulling himself together, the sand shifting back into the shape of something like a man and slithering into the house past Pap sleeping on the porch. One eye dripping black, he’d rise up like a rattler, snatch his teeth from inside her boot, poke them back into his gums, and rip her throat out.

After the third time she jolted up with a fright, alone in the dark with a stick-knife in her fist, she figured to hell with it and just got on up. Despite the drenching Durango heat, she’d taken to dressing like a bandito’s grandmother with one of Pap’s old, faded shirts over her bound chest, baggy pants held up by a rope, and a moth-gnawed serape over that. The less the folks of Gloomy Bluebird could see she was a girl, the less trouble they gave her.

Mam and Pap had taken to sending her on all their errands into town, considering they owed so many debts. Nettie’d learned that if she kept her head down and sucked in her cheeks, folks usually took pity and gave her the tail end of a sack of cornmeal or their most pitiful, nonlaying chicken. At first, she’d been embarrassed. But then she’d overheard two of the old biddy church ladies whispering about how shameful it was for Pap to send his half-breed slave pup around to beg, and she realized that they counted her for less than a dog and Pap only slightly more than that.

Mam and Pap Lonesome were of old East stock, pale as salt fish and just as odorous, with matching hay-colored hair and blue eyes that seemed ever confused thanks to eyelashes and eyebrows as light as dandelion fuzz. The pair were shapeless and old enough to look like someone else’s aunt. Nettie couldn’t have been more different, with medium brown skin that could’ve been called liver chestnut, if she’d been a horse worth noticing. Her hair was thick and frizzy, a dead giveaway to anyone trying to puzzle out her breed. Half black and half Injun, or maybe Aztecan; any way you added it up, the end result was somehow less than the individual components. She was built tall and narrow like a half-starved antelope, with eyes as dark and thick as a storm-mad creek and high cheekbones framing a mouth that had little reason to smile. She was ugly, was all they’d told her. But she didn’t find them beautiful, so what did it matter? The entire town was an eyesore.

It was widely agreed that Gloomy Bluebird was a stupid name for a town, especially considering Old Ollie Hampstead had shot the only bluebird they had back in 1822, right outside what passed as a general store. The damn thing had been stuffed and posed with little skill and now sat proudly on the storekeeper’s counter as a reminder of what looking cheerful and bright would get you in a town as dusty as an old maid’s britches. Nettie herself had seen a bluebird when she was just a little thing, hunting lizards out by the creek. When she’d run home to tell Mam, she’d been told to go fetch a switch for lying. Over time, she’d come to believe she must’ve seen a crow. But crows didn’t have red bellies, did they? At least the town lived up to the gloomy part.

The excitement of last night had burned off, and Nettie was feeling downright gloomy herself, like some part of her had blown away with the impossible, sparkling sand. A strange thing had happened, and she had no one to tell, no one she trusted enough to question. Being alone wasn’t so bad when nothing ever changed, but now Nettie didn’t trust herself, and she was generally the only person she could trust.

Although Pap handled most of her punishment, Mam had once thrashed her for lying about a bluebird, and then thrashed her again when she’d started her monthlies and ruined an old striped mattress and screamed that she was dying. How was she supposed to know that was what women did? Nettie didn’t reckon much about the world, but she knew that what happened last night had changed things as much as her flux blood. The world was suddenly more dangerous, but she had no idea why or how to protect herself from it. Seemed like the best way to keep her skin was to get on with breakfast and not say a danged thing, to hide it like she hid everything else.

When she went to shake her boots for scorpions, it was four pointed teeth that fell out. Considering no crevice of the shack was safe from Mam’s quick fingers, Nettie shoved them into the little leather bag she kept tied around her waist with what few precious things she’d found over the years. A glittery white arrowhead, hardly chipped. A shiny gold button with a bugle on it. A wolf claw, or something like it. A penny given to her once in the town when she’d been kicked in the leg by a frachetty horse. She’d kept a piece of dirt-dusted ribbon candy some town brat had dropped in the pouch for two weeks once, allowing herself one suck a day. The four teeth added a weight barely felt, but she stood a mite taller. Whatever that stranger had been, she’d won. And that felt pretty goddamn good.

Mam and Pap weren’t up, of course. They gave the sun time to stretch and get cozy before they stopped snoring. It was almost peaceful, setting up the porridge in the pot and watching the skillet shimmer with fatback grease. She always loved snatching warm eggs from under the scrawny, sleepy hens; this brood was the result of Pap’s once-a-year victory at the poker table. They’d definitely seen harder times, although Nettie didn’t much get to enjoy the bounty herself. If Mam and Pap left any eggs on their plates, that was usually treat enough.

The sun came up so fast that if you weren’t watching careful, you’d miss it. For just a second, it was a flat circle, hot-red and bleeding all over the soft, purple clouds. Nettie stared at it as long as she could, not blinking, then leaned over to turn the eggs, and when she looked again, the sun sat high and white, relentlessly beating down on the endless prairie. Sunset, at least, took its time, nice and lazy. She liked the colors of it, and the way that no one could own the sun. It couldn’t be compelled, couldn’t be roped. You could yell at it all day long, threaten and plead and cuss, and the sun would not budge a goddamn inch. It was what it was, and it took its damn time about it.

But Nettie had fewer choices, so she quickly bolted down her small share of the porridge. Not only because Mam and Pap would give her an earful if they woke up with her in the house, but also because she wanted to mosey over to the Double TK before the surlier of the cowboys were awake and taking out their hangovers on whoever happened by. The ranch next door was far richer than Pap’s, considering they had more than a one-eyed mule, two nags for renting, a herd of cattle too thin for the butcher to carve, and one milk cow that barely squirted enough milk for weak porridge. Mam had sent her toddling over to the Double TK for the first time to have a knife sharpened when she was just five years old, and Monty had taken her on like a lost pup. The old cowpoke had told her, years later, that they’d figured her for a boy at first, as she’d been in britches and had a shorn head. But since she’d been mannerly and offered to help the wranglers by sweeping out the pen or tossing rocks at vultures, they’d generally tolerated her presence.

Over the years, she’d learned by watching Monty and had figured out better ways to work a colt than using Pap’s whip. She was awful shy of the other cowpokes and never went near the ranch house or Boss Kimble, but Monty said he was right glad for her calm hand with the horses and general quietude. He was still thin and tough as leather, with a luxurious mustache, but she’d noticed that in the last couple of years, Monty had saved the wilder horses for her visits and chosen gentler mounts for himself, and that his mustache had gone to gray.

On her way to the Double TK, she stopped to feed the few critters Pap hadn’t used up yet. Blue greeted her with his usual hollering, and she gave him a once-over and a fine scratch and fed him a precious handful of grain, plus a bite she’d held back from the porridge. He pressed his big, ugly mule nose over her shoulder, and she leaned into his skinny chest and breathed in his good horse smell. He didn’t know he wasn’t a horse, and he didn’t know he was ugly. Pap’s swayback mare, Fussy, took the grain and turned her tail, just as sour as her owner, and the aged nag they called Dusty refused to get up off the ground. The wild black mare was still gone and the water trough still clean, thank heavens. Nettie had already fed the cow and scattered the morning’s corn for the chickens, but the poor things crowded around her with hopeful clucking. It was a sad joke, calling it a ranch.

Before heading off, Nettie snuck into the other barn to see if the stranger’s clothes were . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved