Landry, Landry and Bartlett published literary fiction, historical biographies, and poetry collections, mostly by established poets. The company was founded just after the Second World War, though it seemed to have been fashioned after an older, more venerable model: a long-established family firm. Since the retirement of its ailing co-founder Preston Bartlett III, one heard rumors—whispers, really— that its finances were shaky and its future uncertain, rumors that my uncle seemed delighted to pass on.

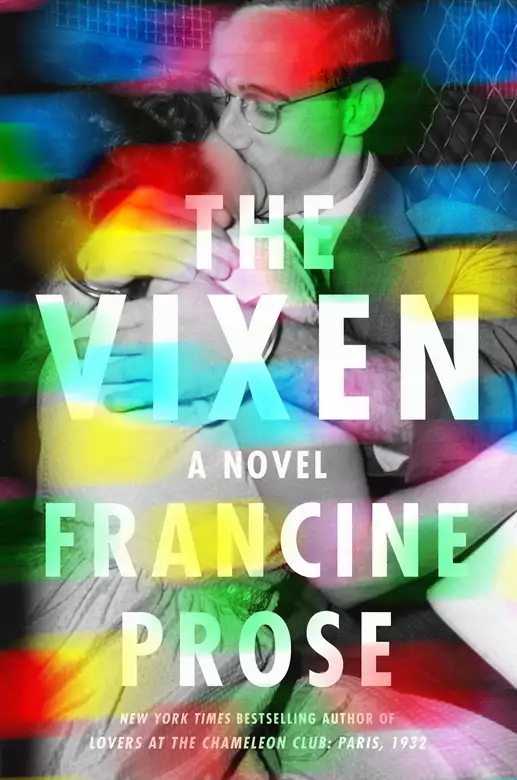

The hope was that the money The Vixen generated might allow us to continue to publish the serious literature for which we were known and respected, and which rarely turned a profit. It was made clear to me that publishing a purely commercial, second-rate novel was a devil’s bargain, but we had no choice. It was a bargain and a choice that our director, Warren Landry, was willing to make.

…

Perhaps this is the point to say that, at that time, my life seemed to me to have been built upon a series of lies. Not flat-out lies, but lies of omission, withheld information, uncorrected misunderstandings. Many young people feel this way. Some people feel it all their lives.

The first lie was the lie of my name. Simon Putnam wasn’t the name of a Jewish guy from Coney Island. It was the name of a Puritan preacher condemning Jewish guys from Coney Island to eternal hellfire and damnation. My father’s last name, my last name, was the prank of an immigration official who, on Thanksgiving Day, in honor of the holiday, gave each new arrival—among them my grandfather—the surname of a Mayflower pilgrim. Since then I have met other descendants of immigrants who landed in Boston during the brief tenure of the patriotic customs officer. Brodsky became Bradstreet, Di Palo became Page, Maslin became Mather. Welcome to America!

And Simon? What about Simon? My mother’s father’s name was Shimon. The translation was imperfect. In the Old Testament, Simon was one of the brothers who tried to murder Joseph.

I hadn’t (or maybe I had) intended to compound these misapprehensions by writing what turned out to be my Harvard admissions essay about the great Puritan sermon, Jonathan Edwards’s “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” delivered in Massachusetts, in 1741. My English teacher, Miss Singer, assigned us to write about something that moved us. Moved, I assumed, could mean frightened. I wanted to write about Dracula, but my mother paged through my American literature textbook and told me to read the Puritans if I wanted to understand our country.

[ Return to the review of “The Vixen.” ]

I wrote about Edwards’s faith that God wanted him to terrify his congregation by describing the vengeance that the deity planned to take on the wicked unbelieving Israelites. It seemed unnecessary to mention that I was one of the sinners whom God planned to throw into the fire. I was afraid that my personal relation to the material might appear to skew my reading of this literary masterpiece.

I had no idea that Miss Singer would send my essay to a friend who worked in the Harvard admissions office. Did Harvard know whom they were admitting? Perhaps the committee imagined that Simon Putnam was a lost Puritan lamb, strayed from the flock and stranded in Brooklyn, a lamb they awarded a full scholarship to bring back into the fold. That Simon Putnam, the prodigal Pilgrim son, was a suit I was trying on, a skin I would stretch and struggle to fit, until I realized, with relief, that it never would.

The Holocaust had taught us: No matter what you believed or didn’t, the Nazis knew who was Jewish. They will always find us, whoever the next they would be. It was not only pointless but wrong—a sin against the six million dead—to deny one’s heritage, though my uncle Madison had done a remarkable job of erasing his class, religious, and ethnic background. I tried not to think about the sin I was half committing as I half pretended to come from a family that was nothing like my family, from a place far from Coney Island. If someone asked me if I was Jewish, I would have said yes, but why would anyone ask Simon Putnam, with his Viking-blond hair and blue eyes? My looks were the result of some recessive gene, or, as my mother said, perhaps some Cossack who rode through a great-great-grandmother’s village.

…

When Harvard ended, in June, I’d returned to Brooklyn without having acquired one useful contact or skill my parents had hoped would be conferred on me, along with my diploma. Another lie of omission: My mother and father were astonished to learn that I had majored in Folklore and Mythology. What kind of subject was that? What had I learned in four years that could be useful to me or anyone else? How could eight semesters of fairy tales prepare me for a career?

Freshman year, I’d taken Professor Robertson Crowley’s popular course, “Mermaids and Talking Reindeer,” because it was a funny title and it sounded easy. After a few weeks, I knew that the tales Crowley collected and his theories about them were what I wanted to study. Handed down over generations, these narratives were not only enthralling but also seemed to me to reveal something deep and mysterious about experience, about nature, about our species, about what it meant to tell a story—what it meant to be human. I wanted to know what Crowley knew, though I wasn’t brave or hardy enough to live among the reindeer herders, shamans, and cave-dwelling witches who’d been his informants. I wanted to be like Crowley more than I wanted to sit on the Supreme Court or win the Nobel Prize or do any of the things my parents dreamed I might do.

Despite everything I have learned since, I can still remember my excitement as I listened to Crowley’s lectures. I felt that I was hearing the answer to a question that I hadn’t known enough to ask. That feeling was a little like falling in love, though, never having fallen in love, I didn’t recognize the emotions that went with it.

By the time I took his class, Crowley was too old for adventure travel. He’d become a kind of Ivy League shaman. Later, he would become the academic guru for Timothy Leary and the LSD experimenters, and soon after that he was encouraged to retire.

Every Thursday morning, the long-white-haired, trim-white-bearded Crowley stood at the bottom of the amphitheater and, with his eyes squeezed shut, told us folktales in the stentorian tones of an Old Testament prophet. Many of these stories have stayed with me, stories about babies cursed at birth, brides turned into foxes, children raised by forest animals. Most were tales of deception, insult, and vengeance. Crowley told story after story, barely pausing between them. I loved the wildness, the plot turns, the delicate balance between the predictable and the surprising. I took elaborate notes.

I had found my direction.

At the start of the second lecture, Crowley told us, “The most important and overlooked difference between people and animals is the desire for revenge. Lions kill when they’re hungry, not to carry out some ancient blood feud that none of the lions can remember.”

He kept returning to the idea that revenge was an essential part of what makes us human. Lying went along with it, rooted deep in our psyches. He ran through lists of wily tricksters—Coyote, Scorpion, Fox—and of heroes, like Odysseus, who disguise themselves and cleverly deflect the enemy’s questions.

It was unsettling to take a course called “Mermaids and Talking Reindeer” that should have been called “Lying and Revenge.” But after a few classes we got used to all the murderous retribution: the reindeer trampling a man who’d killed a fawn, the mermaids drowning the fisherman who’d caught one of their own in his net, the feud between the Albanian sworn virgins and the rapist tribal chieftain. Crowley told so many stories that proved his theories that I began to question what I’d learned from my parents, which was that most human beings, not counting Nazis, sincerely want to be good.

What little I knew about revenge came from noir films and Shakespeare. What would make me want to kill? No one could predict how they’d react when a loved one was threatened or hurt, a home destroyed or stolen. But why would you perpetuate a feud that would doom your great-grandchildren to a future of violence and bloodshed?

I was more familiar with lying. How often had I told my parents that I’d spent the evening studying with my friends when the truth was that we’d ridden the Cyclone, again and again? Lying seemed unavoidable: social lies, little lies, lies of omission and misdirection. I wondered where I would draw the line, what lie I couldn’t tell, and I wondered when and how my limits would be tested.