- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Not Yet Available

Release date: July 7, 2020

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

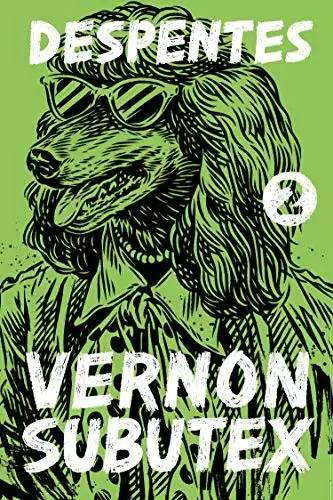

Vernon Subutex 2

Virginie Despentes

VERNON WAITS UNTIL IT’S DARK and the lights in all the windows have been turned out before climbing over the railings and venturing into the communal gardens. The thumb on his left hand is throbbing, he doesn’t remember how he got this little scratch, but rather than scarring, it is swelling, and he is astonished that such a trivial scratch can be causing him so much pain. He crosses the steep ground, past the vines, following a narrow path. He is careful not to disturb anything. He doesn’t want to make any noise, or for there to be any sign of his presence tomorrow morning. He reaches the tap and drinks thriftily. Then he bends down and runs water over the back of his neck. He rubs his face vigorously and soothes his thumb, holding it under the freezing jet for a long time. Yesterday, he took advantage of the warm weather to have more comprehensive ablutions, but his clothes reek so strongly that as soon as he put them on again he felt dirtier than he had before he washed.

He stands up and stretches. His body is heavy. He thinks about a real bed. About lying in a hot bath. But nothing works. He cannot bring himself to care. He is filled with a feeling of utter emptiness, he should find this terrifying, he knows that, this is no time to feel good, but all he feels is a dull, silent calm. He has been very ill. His temperature has come down, and in the past two days he has recovered enough strength to be able to stand up. His mind is weak. It will come back, the fear, it will come back soon, he thinks. At the moment, nothing touches him. He feels suspended, like this strange neighborhood where he has ended up. The butte Bergeyre is a raised plateau of a handful of streets accessed by flights of stairs, he rarely sees a car here, there are no traffic lights, no shops. Nothing but cats, in abundance. Vernon stares across to the Sacré-Coeur, which seems to be floating over Paris. The full moon bathes the city in a ghostly light.

He is off his head. He has episodes where he zones out. It’s not unpleasant. From time to time, he tries to reason with himself: he cannot stay here indefinitely, it has been a cold summer, he will catch another bout of flu, he needs to take care of himself, he needs to go back down into the city, find some clean clothes, do something … But when he tries to set his mind again to practical problems, it starts up: he goes into a tailspin. There is a sound from the clouds, the air against his skin is softer than silk, the darkness has a scent, the city murmurs to him and he can decipher the whisperings that rise and enfold him, he curls up inside it and he floats. Each time, he is unaware how long he spends swept up in this gentle madness. He does not resist. His mind, shaken by the events of recent weeks, seems to have decided to imitate the heady rush of the drugs he used to take in a former life. After each episode, there is a subtle click, a slow awakening: the normal course of his thoughts resumes.

Leaning over the tap, he drinks some more, long gulps that sting his windpipe. His throat aches since his illness. He thought he was going to die there on the bench. The few things he can still feel with any intensity are entirely physical: a terrible burning in his back, the throbbing of his injured hand, the festering sores on his ankles, the difficulty swallowing … He picks an apple from the far end of the garden, it is sour, but he is ravenous for sugar. Painfully, he climbs over the railings separating the communal garden from the property where he has taken to sleeping. He grips the branches and hoists his body up, almost falling flat on his face on the other side. He ends up kneeling on the ground. He wishes he could feel sorry for himself, or disgust. Anything. But no, nothing. Nothing but this absurd calm.

He crosses the yard of the derelict house where he has set up camp. On the ground floor, what was intended to be a patio with panoramic views of the capital is still no more than an expanse of concrete at one end of which he is sheltered from the wind and the rain, the space is marked out by rusting iron girders. Work on the site had been abandoned several years ago, Vernon had recently been told by a guy working on a building site opposite. The original foundations had been threatening to collapse, there were cracks in the supporting walls so the owner had decided to entirely remodel the house. But he had died in a car accident. His heirs could not reach an agreement. They bickered and fought through their respective lawyers. The house was boarded up and left derelict. Vernon has been sleeping here for some time now, whether ten days or a month he could not say—his sense of time, like everything else, is murky. He likes his hideaway. At dawn, he opens one eye and lies motionless, struck by the sweeping cityscape. Paris is revealed and, seen from this height, it seems welcoming. When the cold gets to be too biting, he curls up and tucks his knees against his body. He doesn’t have a blanket. He has only his own body heat. A fat, one-eyed tabby cat sometimes comes and nestles next to him.

On his first few nights in the butte Bergeyre, Vernon slept on the bench where he collapsed when he first got there. It rained nonstop for days. No one bothered him. Delirious and running a high fever, he had embarked on a fantastical journey, feverishly raving. Gradually, he had come back to himself, reluctantly reemerging from the cozy cotton ball of his hallucinations. An old wino found him on the bench at daybreak and started hurling abuse at him, but seeing that Vernon was too weak to respond, he started to worry about his condition, and developed an affection for him. He brought him some oranges and a box of Tylenol. Charles is a loudmouth and pretty crazy. He likes to kvetch, to ramble on about his native Northern France and his father, who was a railwayman. He laughs hysterically at his own jokes, slapping his thighs, until the laugh turns into a phlegmy cough that all but chokes him. Vernon has taken up residence on “his” bench. After a cursory evaluation whose criteria are unknown even to him, the old man decides to be his friend. He takes care of him. He comes by to check that all is well. He warned Vernon: “You can’t go on sleeping here now that the weather’s cleared up,” and pointed to a house a few feet away. “Get yourself in there and hide out in the back. Make sure you disappear for a couple of hours a day, otherwise the council workers won’t waste any time throwing your ass out. Do it now, because you need to get some rest, get yourself fit, son…”

Vernon did not heed the warning, but on the second sunny day, he discovered that it had been sound advice. The street cleaners were hosing down the sidewalks. He didn’t hear them coming. One of them trained the hose right on his face. Vernon scrabbled to his feet and the cleaner flushed away the cardboard boxes he was using to shelter from the cold. The young black guy with delicate features gave him a hateful stare. “Get the fuck out of here. People don’t want to have to look at your shiftless mug when they open their windows. Go on, fuck off.” And, from the guy’s tone, Vernon realized he would be wise to obey, and fast: otherwise he was in for a kicking. His legs numb from spending so long lying down, he had staggered away and aimlessly roamed the neighboring streets. He listened for the sound of the street sweeper’s engine and tried to get as far away as possible. The injustice of the situation left him completely unmoved. This was the day that he began to understand that there was something seriously wrong with him. He wondered where he had washed up. It took him some time to work out why the area looked so unfamiliar: he could see no cars, could hear no sounds. All he could see were old-style, low-rise houses with little yards. Were it not for the fact that the bench he had just left had a view of Sacré-Coeur, he would have thought that in his bout of fever, he had hopped on a train and wound up at the ass end of nowhere. Or in the 1980s …

Too weak to carry on his perambulations, he went back to the bench as soon as the street sweeper drove away. Rubbing his cheeks with his palms, he was surprised to discover how much his beard had grown. His whole body ached from the cold, he was thirsty, and he stank of piss. He had a clear memory of the events of the previous days. He had abandoned his friend at a hospital after a street brawl that had left Xavier in a coma, without so much as asking whether he would pull through. He had wandered in the rain and found himself here, sick as a dog and happy as a fool. But though he has been expecting it, he has yet to feel the vicious sting of fear. Fear might have prompted him to react. But he senses only his aching body, his own smell, which, truth be told, provided pleasant company. He no longer experienced ordinary emotions. He spent his time staring at the sky, it occupied his days. Just before nightfall, Charles had come back to sit next to him on the bench.

“Good to see you emerging from your lethargy. About time too!”

Charles had explained that he was in northern Paris, not far from the Buttes-Chaumont. Charles had offered him a beer and half a soggy, squashed baguette that had obviously been lying around in his backpack for some time, and Vernon wolfed it down. “Fuck sake, go easy there or you’ll make yourself sick. You gonna be here tomorrow? I’ll bring you some ham, you need something to buck you up a bit.” The old man was not a tramp, his hands were not calloused, his shoes were new. But he was not exactly fresh as a daisy either. He seemed to spend his time boozing with guys who smelled of piss. He and Vernon sat together for a while, not saying much.

Since then, Vernon has felt weightless. An invisible hand has fiddled with all the buttons on his mixing desk: the equalization is different. He somehow cannot leave this bench. For as long as he is not forcibly ejected, the butte Bergeyre hangs suspended, a tiny, hovering island. He feels good here.

He takes short walks to stretch his legs, and so that he does not spend all day on the bench. Sometimes he will sit on the steps that border his territory, or linger in a street, but he always returns to his point of departure. His bench, opposite the communal gardens, with its stunning view of the rooftops of Paris. He begins to establish a routine.

At first, the builders working on the rue Remy-de-Gourmont ignored him. Then the site foreman came over on one of his breaks and smoked a cigarette while making a telephone call. He had walked straight over to the bench and Vernon had given up his seat, moving away, eager to be invisible, when the guy called to him: “Hey, I’ve been watching you for a couple of days now … Didn’t you used to have a record shop?” Vernon had hesitated—it was on the tip of his tongue to say “No” and go on his way. He was no longer interested in his previous identity. It had slipped from his back like an old coat, heavy and unwieldy. The person he had been for decades had nothing to do with him now. But the foreman didn’t give him a chance—“You don’t remember me, do you? I used to work next door, I was an apprentice in the bakery … I used to pop in all the time.” The face did not ring a bell. Vernon had spread his hands—“I haven’t really got all my marbles anymore”—and the guy had laughed—“Yeah, I get it, life’s fucked you over” … Since then, he comes by every day to chat for a couple of minutes. When you live on the streets, anything that has happened three days in a row is a venerable tradition. Stéphane wears Bermuda shorts and huge sneakers, he has curly hair and smokes hand-rolled cigarettes. He likes to reminisce about the music festivals he went to, to talk about his kids and bitch about his problems with the guys on the building site. He avoids any reference to the fact that Vernon is living on the streets. Hard to say whether this is extraordinary tact on his part or sheer thoughtlessness. He lets Vernon help himself from his pouch of tobacco, sometimes leaves him a bag of chips or the dregs of a bottle of Coke … And he allows him to use the site toilets during the day. This changes everything for Vernon, who has had to dig two trenches in the yard of the house where he sleeps, but even in warm weather it’s difficult digging deep holes with your bare hands and filling them in so they don’t stink … even short-term, it would have brought an end to his squat. Sooner or later, the local residents would have started complaining about the smell.

For the past three days, Jeanine has been secretly coming to visit him. She also feeds stray cats. She brings Vernon food in Tupperware boxes. She does it furtively because the locals have already had harsh words with her about encouraging the homeless to hang around. Vernon is not the first. She told him as much: at first, everyone thought it was a kindness, they wanted to help their fellow man, but there were too many problems: traces of vomit, a radio left on full-blast all night, a garrulous oddball with no sense of boundaries who wanted to go into people’s houses and chat, some guy on psychotropic drugs who talked to himself and scared the local kids … The neighbors had no choice: they had to curb their compassion. Jeanine persists in sharing her dinner with him. She is a tiny little old lady, stooped, well-turned-out, the eyebrows drawn on with pencil are asymmetrical, but her lipstick is always neatly applied, and perfect curls of white hair frame her powdered face. “When I’m at home, I wear curlers all morning, and I’m not going to stop until they put me in the ground.” She dresses in bright colors and complains about the terrible summer weather, because of the pretty dresses she has not been able to wear, “and I don’t know whether I’ll still be here next summer to get the use out of them.” She tells Vernon he is a “little dear, you can tell these things when you get to my age, I’ve got the eye, you’re a little dear, and you have such lovely eyes.” She says the same thing to the stray cats she feeds. She fills bottles of water for Vernon, brings him rice in which she has melted generous quantities of butter. She passes no comment, but Vernon suspects that she assumes that whatever is good for keeping a cat’s coat glossy is good for people. Last night, she brought a few squares of chocolate wrapped in foil. He was shocked by the pleasure he felt as he ate them. For a brief moment, his taste buds almost hurt. He had already forgotten what it was like to put something in his mouth and enjoy the taste.

AS HE DOES EVERY DAY AT ABOUT SIX O’CLOCK, Charles leaves the bookie’s on the rue des Pyrénées and walks up the avenue Simon-Bolivar to the grocer’s near the gates of the park. The boy behind the counter isn’t one for smiling. He barely tears his eyes from the television on which he is watching the cricket as he gives him his change.

The old man slowly trudges into the parc des Buttes-Chaumont. He is in no hurry. Outside the little Punch and Judy theater, parents are waiting in silence. Inside, their brats are screaming “He’s behind you!” Charles’s bench of choice is on the left, not far from the public toilets. With the flat of his hand, he wipes down the green wooden slats, invariably daubed with mud where some asshole propped his sneakers on the bench to do elevated push-ups. He pops the cap on his first beer using a cigarette lighter. Opposite, two cats are circling, sizing each other up, unsure whether to launch into a scrap.

Charles has always liked this park. Having spent the afternoon sheltering from the pale afternoon light in the dark recesses of a bar, he always comes here for his aperitif. The only problem with the Buttes-Chaumont is the gradient; one of these days, he’ll drop dead climbing the hill.

Laurent comes to join him. He knows his schedule. He always has a beer for him. He endlessly trots out the same five or six stories, punctuated by a booming laugh. The tenth time they heard him bragging about the same fistfight, anyone would feel like telling him to change the record, but Charles does not ask much of his drinking buddies. You can’t be a boozer and be choosy about the company you keep. Laurent is part of his day. Obviously, he would rather it was fat Olga who joined him for his aperitif. He’s always had a soft spot for crazy women. He would happily put up with a whole heap of shit, if on a summer’s evening Olga would whisper sweet nothings in his ear. The first time he saw her, she was wearing apple-green clogs, he had mercilessly mocked her, calling her Bozo the Clown, and she had given him a slap around the face. Charles had to give as good as he got. Olga would have liked to return blow for blow, but she can’t help it, she’s soft-hearted. When she punches, it’s like a kiss. The old man was touched, seeing her hold her own with such conviction, he feels nothing but affection for her. She still bears a grudge because of that first encounter. He likes his women mad and ugly. He’s always pretended the contrary. He nods and agrees when friends talk about women who are no trouble as though they are gems to be treasured, he has often pretended that he dreams of a pretty little thing who wouldn’t bust his balls or throw things but that’s just part of the bullshit men like him tell each other: back when he could have landed himself a nice woman, he stayed with Véro, and every time he’s cheated on her it’s been with women who are no oil paintings. It takes all sorts to make a world. Nice women bore him rigid.

The paths in the park are quagmires. It rained for hours. It’s all anyone seems to talk about in the bar these days, the terrible spring they’ve had. It’ll be a while before people come back for a Sunday stroll. The only people around are the joggers, who seem to have been hiding out in the bushes ready to jump out, panting like they’re being tortured. Some of them, it’s so obvious that what they’re putting themselves through is dangerous to their health. Laurent stares down at his shoes in disgust:

“I don’t suppose you take a size forty?”

“I wear a forty-four. Why are you asking me that?”

“You always have nice shoes. I’m looking for a pair at the moment … I don’t like these.”

“Those are work boots you’ve got on. They’re really uncomfortable.”

“I dragged myself all the way down to the Secours populaire to get shoes … they didn’t have anything. The economy is fucked, people are hanging on to their stuff.”

“Tough shit.”

“I’ll head up to rue Ramponeau tomorrow, maybe they’ll have something in my size, these are chafing my heels, I’ll end up with blisters.”

* * *

On the next bench, a heavyset black man in a silver tracksuit is hectoring some puny little white guy in shorts. In a booming voice, the trainer roars: “Don’t stop, don’t stop, pick it up, come on, pick up the pace!” and the scrawny wimp is bobbing up and down, staring into space, dog-tired and looking like he might have a heart attack. Laurent wastes little time on them, he is fascinated by a big lump of a girl staggering up the path in blue overalls like a drunken cosmonaut. Charles passes Laurent another bottle and says:

“If it was down to me, I wouldn’t allow any sports freaks in the park. They ruin the atmosphere.”

“You’d deprive us of all the pretty little things running around half naked? I mean, take the girl coming toward us right now—it would be a terrible shame if she didn’t get to show off her wares…”

The problem with guys like Laurent—and they are legion—is that you can always predict their reactions. The slim, blond-haired student jogging down the path is of no possible interest. The sort of girl who smells of soap even when she’s running. Not that Charles has a moral scale he applies to the libidos of others. But guys these days are all the same, it’s like they take night classes to be as much like each other as possible. If you split Laurent’s brain in two to look at the inner workings, you’d find exactly the same bullshit dreams as you would in the wheezing middle-manager doing abdominal crunches at the next bench: fat-free, zero-sugar girls, a bit of bling by Rolex and a big house by the sea. Dumb fuck dreams.

There is an order of magnitude between his generation and Laurent’s. His generation didn’t idolize the bourgeoisie. Whatever they claim, the working classes today all wish they’d been born on the right side of the tracks. In Lessines, the town where he grew up, the day was governed by the rhythm of the sirens at the local quarries. They despised the middle-class people from the other side of town. You didn’t drink with your boss. It was a law. In the bars, people talked of nothing but politics, class hatred nurtured a veritable proletarian aristocracy. People knew how to despise their boss. That’s all gone now, and with it the satisfaction of a job well done. There is no working-class consciousness anymore. The only thing that matters to them today is being just like their boss. Give a guy like Laurent power, and he wouldn’t want to force the rich to redistribute their wealth, he’d want to join their clubs. There has been a standardization of desire: they’re all free-market reactionaries. They’d make good cannon fodder.

Farther down the path, standing next to a bank of flowers, four park keepers are smoking with a man in a gray suit. A smiling, broad-shouldered Asian guy, a regular in the park who always wears a Stetson, is walking backward up a steep lawn. He always does this when he comes here, he never talks to anyone. A short-legged, long-haired gray dog runs around him in circles. Charles turns to his drinking buddy:

“Any idea why the Chinese do that?”

“Run up hills backward? Not a clue. Different cultures, isn’t it?”

“That’s true, it’s not something we’d normally do.”

Since spring, Laurent has been living on the abandoned railway track that runs through the park at the bottom of the hill. Not many of them sleep there, and the park keepers turn a blind eye as long as no one walks on the grass at night.

A woman hesitates near the bench where they are sitting as though she has lost her way. She is wearing a long red coat buttoned up the front, the sort of coat a little girl might wear; it accentuates her wizened face. She must be a schoolteacher. If she had more contact with adults, she wouldn’t be wearing a coat like that. Laurent raises a hand and waves when he spots her. She seems surprised at first, then recognizes him and comes over:

“Hello. How are things?”

“Cool. Care for a swig?” he says, proffering his cheap wine.

Instinctively, she takes a step back, as though he might force the bottle into her mouth.

“No, no, no thanks. I’m looking for a bar called Rosa Bonheur, do you know which way it is?”

“Always looking for something or other, you…”

Laurent is playing the lady-killer. Charles is embarrassed for him. For fuck’s sake, what are you thinking, expecting a clean, well-dressed woman to drink out of your bottle and listen to your shtick?

“If you’re looking for Rosa Bonheur, it’s simple, take that street there, go straight on, about five hundred yards. Did you ever find that guy, Subutex?”

“No. You never saw him again?”

“Nope … but I can take your details and if I hear anything, I’ll let you know…”

Laurent reels off his patter in the tone of a receptionist. He puffs out his chest, opens the zipper of his thick khaki gabardine, takes out a battered orange notepad, and, flashing a toothless grin, asks the lady to lend him a pen. He’s a pitiful sight when he tries to seem urbane. The lady in the red coat gives a slightly irritated pout and mechanically tugs at a hair between her eyes. Laurent carries on blathering as usual—when he finds himself a new audience, he doesn’t give up easily.

“Vernon got into a right mess because he was hanging out with the wrong tart … You see it a lot in newbies: too easygoing. If I’d seen him with Olga, I would have warned him to watch out. Everyone gets fooled. She seems nice enough at first, but if you hang out with her you end up facedown in the shit … It’s no life for women, living on the streets. And anyway, it’s easier for them to avoid it. If Olga had squeezed out two or three brats when she still could, she’d be entitled to loads of benefits, and let me tell you something, if you’re a single mother, they’ll find you fucking social housing. Guys like us, single men with no kids, we can drop dead … oh, but families, they’re sacred! Not her though, oh no, too much effort to crank out a kid … a useless bitch, that’s Olga. She has to do everything like a man … except when it comes to brawls, oh, she’s more than happy to throw the first punch, but the one who takes the punches is the guy who’s with her…”

“If you do see Vernon, tell him we’re looking for him, yeah? Tell him Émilie, Xavier, Patrice, Pamela, Lydia … we’re all looking for him. Tell him we’re worried … and that we have stuff to tell him, important stuff…”

“So, you gonna give me your number? And what did you say your name was?”

* * *

The woman in the red coat does not know how to say no. Her name is Émilie; reluctantly she mumbles her mobile phone number, then rushes off. She is a little wide in the hips, she moves unsteadily. “Where the fuck d’you know her from?” Charles says.

“There’re a whole bunch of them,” Laurent crows. “All looking for Vernon Subutex, but I’ve no idea where the bastard’s gone…”

“Who is this guy?”

“A loser. New guy. The sort you know can’t hack it. Too weak. Too delicate. I dunno where he’s gone, but it was obvious that the guy would never cut it, living on the street. At least ex-junkies have some experience with it, not him though … too la-di-da. He got in one brawl after another until some friend of his got beaten senseless and left for dead on the street. And then the guy up and disappears. His friends have been trying to track him down ever since…”

“She didn’t seem angry.”

“Oh, no, I don’t think they’re looking to give him a beating … they’re just a bunch of headbangers who’ve been hanging around the park looking for Subutex the last three days.”

“So what does he look like, this guy?”

“French, skinny, nice eyes, long hair, comes on like some faggotty rock star … He’s not much to look at, actually, but he’s a straight-up guy.”

The description sounds a lot like the guy up on the butte Bergeyre. Charles is wary. The guy was so sick, the old man thought he would croak right there on the bench. If he’s in hiding, he’s probably got good reason. We all have our secrets, and we all have our own way of dealing with them.

“So you’ve no idea why she’s looking for him, this woman?”

“Why are you so interested?”

“It’s not exactly common, a lady like that looking for a homeless guy…”

“Never trust women. They’re always hiding something … it’s probably something to do with death.”

“Death?”

“Women are always going on about how all they care about is kids … having kids, looking after kids, all that shit … and we’d like to believe them. But think about it. The only thing women are obsessed with is dead people. That’s their thing. They never forget. They want to avenge them, want to bury them, want to make sure they rest in peace, want people to honor their memory … women don’t believe in death. They just can’t bring themselves to. That’s the real difference between us and them.”

“I don’t know where you came up with that bullshit theory, but I suppose at least it’s original.”

“Think about it when you’re sleeping off the booze tonight. You’ll see. It makes sense.”

“That still doesn’t explain why she’s looking for this guy.”

“No. But I’m happy to shoot the breeze with a lady. I’m an obliging sort of guy. And I like women like her, timid, straitlaced, makes me want to give it to her, wham bam, thank you, ma’am…”

* * *

Charles leaves him to his lecherous ramblings. He is still surprised that the woman in the red coat deigned to talk to them. Charles looks like a tramp. People are reluctant to talk to him. But when he feels like talking to someone, he knows how to go about it. It’s like pigeons and crows; you have to regularly feed them little crumbs of attention. His approach is the same as the little old lady he used to run into around the neighborhood until last summer. She lived on the rue Belleville, and when she came out of her house at six o’clock, the pigeons recognized her. They would flock to her in huge numbers, in the air and on the ground, and follow her. She would scatter fistfuls of seeds and bread crumbs around the base of the trees along the avenue. Feeding pigeons is banned. To anyone who didn’t know what she was up to, the flights of birds synchronously swooping along the avenue Simon-Bolivar were very unsettling. One day, her kids put her in a home. Charles heard the news in the bar opposite the park gates. The old woman owned her apartment. The kids probably sensed the wind changing, the housing crisis coming, they wanted to sell up before the market crashed. Off to the slaughterhouse. She was a frisky old dame, had never touched a drink, the one pleasure of her dotage was feeding the pigeons when she went out for a walk … she was

He stands up and stretches. His body is heavy. He thinks about a real bed. About lying in a hot bath. But nothing works. He cannot bring himself to care. He is filled with a feeling of utter emptiness, he should find this terrifying, he knows that, this is no time to feel good, but all he feels is a dull, silent calm. He has been very ill. His temperature has come down, and in the past two days he has recovered enough strength to be able to stand up. His mind is weak. It will come back, the fear, it will come back soon, he thinks. At the moment, nothing touches him. He feels suspended, like this strange neighborhood where he has ended up. The butte Bergeyre is a raised plateau of a handful of streets accessed by flights of stairs, he rarely sees a car here, there are no traffic lights, no shops. Nothing but cats, in abundance. Vernon stares across to the Sacré-Coeur, which seems to be floating over Paris. The full moon bathes the city in a ghostly light.

He is off his head. He has episodes where he zones out. It’s not unpleasant. From time to time, he tries to reason with himself: he cannot stay here indefinitely, it has been a cold summer, he will catch another bout of flu, he needs to take care of himself, he needs to go back down into the city, find some clean clothes, do something … But when he tries to set his mind again to practical problems, it starts up: he goes into a tailspin. There is a sound from the clouds, the air against his skin is softer than silk, the darkness has a scent, the city murmurs to him and he can decipher the whisperings that rise and enfold him, he curls up inside it and he floats. Each time, he is unaware how long he spends swept up in this gentle madness. He does not resist. His mind, shaken by the events of recent weeks, seems to have decided to imitate the heady rush of the drugs he used to take in a former life. After each episode, there is a subtle click, a slow awakening: the normal course of his thoughts resumes.

Leaning over the tap, he drinks some more, long gulps that sting his windpipe. His throat aches since his illness. He thought he was going to die there on the bench. The few things he can still feel with any intensity are entirely physical: a terrible burning in his back, the throbbing of his injured hand, the festering sores on his ankles, the difficulty swallowing … He picks an apple from the far end of the garden, it is sour, but he is ravenous for sugar. Painfully, he climbs over the railings separating the communal garden from the property where he has taken to sleeping. He grips the branches and hoists his body up, almost falling flat on his face on the other side. He ends up kneeling on the ground. He wishes he could feel sorry for himself, or disgust. Anything. But no, nothing. Nothing but this absurd calm.

He crosses the yard of the derelict house where he has set up camp. On the ground floor, what was intended to be a patio with panoramic views of the capital is still no more than an expanse of concrete at one end of which he is sheltered from the wind and the rain, the space is marked out by rusting iron girders. Work on the site had been abandoned several years ago, Vernon had recently been told by a guy working on a building site opposite. The original foundations had been threatening to collapse, there were cracks in the supporting walls so the owner had decided to entirely remodel the house. But he had died in a car accident. His heirs could not reach an agreement. They bickered and fought through their respective lawyers. The house was boarded up and left derelict. Vernon has been sleeping here for some time now, whether ten days or a month he could not say—his sense of time, like everything else, is murky. He likes his hideaway. At dawn, he opens one eye and lies motionless, struck by the sweeping cityscape. Paris is revealed and, seen from this height, it seems welcoming. When the cold gets to be too biting, he curls up and tucks his knees against his body. He doesn’t have a blanket. He has only his own body heat. A fat, one-eyed tabby cat sometimes comes and nestles next to him.

On his first few nights in the butte Bergeyre, Vernon slept on the bench where he collapsed when he first got there. It rained nonstop for days. No one bothered him. Delirious and running a high fever, he had embarked on a fantastical journey, feverishly raving. Gradually, he had come back to himself, reluctantly reemerging from the cozy cotton ball of his hallucinations. An old wino found him on the bench at daybreak and started hurling abuse at him, but seeing that Vernon was too weak to respond, he started to worry about his condition, and developed an affection for him. He brought him some oranges and a box of Tylenol. Charles is a loudmouth and pretty crazy. He likes to kvetch, to ramble on about his native Northern France and his father, who was a railwayman. He laughs hysterically at his own jokes, slapping his thighs, until the laugh turns into a phlegmy cough that all but chokes him. Vernon has taken up residence on “his” bench. After a cursory evaluation whose criteria are unknown even to him, the old man decides to be his friend. He takes care of him. He comes by to check that all is well. He warned Vernon: “You can’t go on sleeping here now that the weather’s cleared up,” and pointed to a house a few feet away. “Get yourself in there and hide out in the back. Make sure you disappear for a couple of hours a day, otherwise the council workers won’t waste any time throwing your ass out. Do it now, because you need to get some rest, get yourself fit, son…”

Vernon did not heed the warning, but on the second sunny day, he discovered that it had been sound advice. The street cleaners were hosing down the sidewalks. He didn’t hear them coming. One of them trained the hose right on his face. Vernon scrabbled to his feet and the cleaner flushed away the cardboard boxes he was using to shelter from the cold. The young black guy with delicate features gave him a hateful stare. “Get the fuck out of here. People don’t want to have to look at your shiftless mug when they open their windows. Go on, fuck off.” And, from the guy’s tone, Vernon realized he would be wise to obey, and fast: otherwise he was in for a kicking. His legs numb from spending so long lying down, he had staggered away and aimlessly roamed the neighboring streets. He listened for the sound of the street sweeper’s engine and tried to get as far away as possible. The injustice of the situation left him completely unmoved. This was the day that he began to understand that there was something seriously wrong with him. He wondered where he had washed up. It took him some time to work out why the area looked so unfamiliar: he could see no cars, could hear no sounds. All he could see were old-style, low-rise houses with little yards. Were it not for the fact that the bench he had just left had a view of Sacré-Coeur, he would have thought that in his bout of fever, he had hopped on a train and wound up at the ass end of nowhere. Or in the 1980s …

Too weak to carry on his perambulations, he went back to the bench as soon as the street sweeper drove away. Rubbing his cheeks with his palms, he was surprised to discover how much his beard had grown. His whole body ached from the cold, he was thirsty, and he stank of piss. He had a clear memory of the events of the previous days. He had abandoned his friend at a hospital after a street brawl that had left Xavier in a coma, without so much as asking whether he would pull through. He had wandered in the rain and found himself here, sick as a dog and happy as a fool. But though he has been expecting it, he has yet to feel the vicious sting of fear. Fear might have prompted him to react. But he senses only his aching body, his own smell, which, truth be told, provided pleasant company. He no longer experienced ordinary emotions. He spent his time staring at the sky, it occupied his days. Just before nightfall, Charles had come back to sit next to him on the bench.

“Good to see you emerging from your lethargy. About time too!”

Charles had explained that he was in northern Paris, not far from the Buttes-Chaumont. Charles had offered him a beer and half a soggy, squashed baguette that had obviously been lying around in his backpack for some time, and Vernon wolfed it down. “Fuck sake, go easy there or you’ll make yourself sick. You gonna be here tomorrow? I’ll bring you some ham, you need something to buck you up a bit.” The old man was not a tramp, his hands were not calloused, his shoes were new. But he was not exactly fresh as a daisy either. He seemed to spend his time boozing with guys who smelled of piss. He and Vernon sat together for a while, not saying much.

Since then, Vernon has felt weightless. An invisible hand has fiddled with all the buttons on his mixing desk: the equalization is different. He somehow cannot leave this bench. For as long as he is not forcibly ejected, the butte Bergeyre hangs suspended, a tiny, hovering island. He feels good here.

He takes short walks to stretch his legs, and so that he does not spend all day on the bench. Sometimes he will sit on the steps that border his territory, or linger in a street, but he always returns to his point of departure. His bench, opposite the communal gardens, with its stunning view of the rooftops of Paris. He begins to establish a routine.

At first, the builders working on the rue Remy-de-Gourmont ignored him. Then the site foreman came over on one of his breaks and smoked a cigarette while making a telephone call. He had walked straight over to the bench and Vernon had given up his seat, moving away, eager to be invisible, when the guy called to him: “Hey, I’ve been watching you for a couple of days now … Didn’t you used to have a record shop?” Vernon had hesitated—it was on the tip of his tongue to say “No” and go on his way. He was no longer interested in his previous identity. It had slipped from his back like an old coat, heavy and unwieldy. The person he had been for decades had nothing to do with him now. But the foreman didn’t give him a chance—“You don’t remember me, do you? I used to work next door, I was an apprentice in the bakery … I used to pop in all the time.” The face did not ring a bell. Vernon had spread his hands—“I haven’t really got all my marbles anymore”—and the guy had laughed—“Yeah, I get it, life’s fucked you over” … Since then, he comes by every day to chat for a couple of minutes. When you live on the streets, anything that has happened three days in a row is a venerable tradition. Stéphane wears Bermuda shorts and huge sneakers, he has curly hair and smokes hand-rolled cigarettes. He likes to reminisce about the music festivals he went to, to talk about his kids and bitch about his problems with the guys on the building site. He avoids any reference to the fact that Vernon is living on the streets. Hard to say whether this is extraordinary tact on his part or sheer thoughtlessness. He lets Vernon help himself from his pouch of tobacco, sometimes leaves him a bag of chips or the dregs of a bottle of Coke … And he allows him to use the site toilets during the day. This changes everything for Vernon, who has had to dig two trenches in the yard of the house where he sleeps, but even in warm weather it’s difficult digging deep holes with your bare hands and filling them in so they don’t stink … even short-term, it would have brought an end to his squat. Sooner or later, the local residents would have started complaining about the smell.

For the past three days, Jeanine has been secretly coming to visit him. She also feeds stray cats. She brings Vernon food in Tupperware boxes. She does it furtively because the locals have already had harsh words with her about encouraging the homeless to hang around. Vernon is not the first. She told him as much: at first, everyone thought it was a kindness, they wanted to help their fellow man, but there were too many problems: traces of vomit, a radio left on full-blast all night, a garrulous oddball with no sense of boundaries who wanted to go into people’s houses and chat, some guy on psychotropic drugs who talked to himself and scared the local kids … The neighbors had no choice: they had to curb their compassion. Jeanine persists in sharing her dinner with him. She is a tiny little old lady, stooped, well-turned-out, the eyebrows drawn on with pencil are asymmetrical, but her lipstick is always neatly applied, and perfect curls of white hair frame her powdered face. “When I’m at home, I wear curlers all morning, and I’m not going to stop until they put me in the ground.” She dresses in bright colors and complains about the terrible summer weather, because of the pretty dresses she has not been able to wear, “and I don’t know whether I’ll still be here next summer to get the use out of them.” She tells Vernon he is a “little dear, you can tell these things when you get to my age, I’ve got the eye, you’re a little dear, and you have such lovely eyes.” She says the same thing to the stray cats she feeds. She fills bottles of water for Vernon, brings him rice in which she has melted generous quantities of butter. She passes no comment, but Vernon suspects that she assumes that whatever is good for keeping a cat’s coat glossy is good for people. Last night, she brought a few squares of chocolate wrapped in foil. He was shocked by the pleasure he felt as he ate them. For a brief moment, his taste buds almost hurt. He had already forgotten what it was like to put something in his mouth and enjoy the taste.

AS HE DOES EVERY DAY AT ABOUT SIX O’CLOCK, Charles leaves the bookie’s on the rue des Pyrénées and walks up the avenue Simon-Bolivar to the grocer’s near the gates of the park. The boy behind the counter isn’t one for smiling. He barely tears his eyes from the television on which he is watching the cricket as he gives him his change.

The old man slowly trudges into the parc des Buttes-Chaumont. He is in no hurry. Outside the little Punch and Judy theater, parents are waiting in silence. Inside, their brats are screaming “He’s behind you!” Charles’s bench of choice is on the left, not far from the public toilets. With the flat of his hand, he wipes down the green wooden slats, invariably daubed with mud where some asshole propped his sneakers on the bench to do elevated push-ups. He pops the cap on his first beer using a cigarette lighter. Opposite, two cats are circling, sizing each other up, unsure whether to launch into a scrap.

Charles has always liked this park. Having spent the afternoon sheltering from the pale afternoon light in the dark recesses of a bar, he always comes here for his aperitif. The only problem with the Buttes-Chaumont is the gradient; one of these days, he’ll drop dead climbing the hill.

Laurent comes to join him. He knows his schedule. He always has a beer for him. He endlessly trots out the same five or six stories, punctuated by a booming laugh. The tenth time they heard him bragging about the same fistfight, anyone would feel like telling him to change the record, but Charles does not ask much of his drinking buddies. You can’t be a boozer and be choosy about the company you keep. Laurent is part of his day. Obviously, he would rather it was fat Olga who joined him for his aperitif. He’s always had a soft spot for crazy women. He would happily put up with a whole heap of shit, if on a summer’s evening Olga would whisper sweet nothings in his ear. The first time he saw her, she was wearing apple-green clogs, he had mercilessly mocked her, calling her Bozo the Clown, and she had given him a slap around the face. Charles had to give as good as he got. Olga would have liked to return blow for blow, but she can’t help it, she’s soft-hearted. When she punches, it’s like a kiss. The old man was touched, seeing her hold her own with such conviction, he feels nothing but affection for her. She still bears a grudge because of that first encounter. He likes his women mad and ugly. He’s always pretended the contrary. He nods and agrees when friends talk about women who are no trouble as though they are gems to be treasured, he has often pretended that he dreams of a pretty little thing who wouldn’t bust his balls or throw things but that’s just part of the bullshit men like him tell each other: back when he could have landed himself a nice woman, he stayed with Véro, and every time he’s cheated on her it’s been with women who are no oil paintings. It takes all sorts to make a world. Nice women bore him rigid.

The paths in the park are quagmires. It rained for hours. It’s all anyone seems to talk about in the bar these days, the terrible spring they’ve had. It’ll be a while before people come back for a Sunday stroll. The only people around are the joggers, who seem to have been hiding out in the bushes ready to jump out, panting like they’re being tortured. Some of them, it’s so obvious that what they’re putting themselves through is dangerous to their health. Laurent stares down at his shoes in disgust:

“I don’t suppose you take a size forty?”

“I wear a forty-four. Why are you asking me that?”

“You always have nice shoes. I’m looking for a pair at the moment … I don’t like these.”

“Those are work boots you’ve got on. They’re really uncomfortable.”

“I dragged myself all the way down to the Secours populaire to get shoes … they didn’t have anything. The economy is fucked, people are hanging on to their stuff.”

“Tough shit.”

“I’ll head up to rue Ramponeau tomorrow, maybe they’ll have something in my size, these are chafing my heels, I’ll end up with blisters.”

* * *

On the next bench, a heavyset black man in a silver tracksuit is hectoring some puny little white guy in shorts. In a booming voice, the trainer roars: “Don’t stop, don’t stop, pick it up, come on, pick up the pace!” and the scrawny wimp is bobbing up and down, staring into space, dog-tired and looking like he might have a heart attack. Laurent wastes little time on them, he is fascinated by a big lump of a girl staggering up the path in blue overalls like a drunken cosmonaut. Charles passes Laurent another bottle and says:

“If it was down to me, I wouldn’t allow any sports freaks in the park. They ruin the atmosphere.”

“You’d deprive us of all the pretty little things running around half naked? I mean, take the girl coming toward us right now—it would be a terrible shame if she didn’t get to show off her wares…”

The problem with guys like Laurent—and they are legion—is that you can always predict their reactions. The slim, blond-haired student jogging down the path is of no possible interest. The sort of girl who smells of soap even when she’s running. Not that Charles has a moral scale he applies to the libidos of others. But guys these days are all the same, it’s like they take night classes to be as much like each other as possible. If you split Laurent’s brain in two to look at the inner workings, you’d find exactly the same bullshit dreams as you would in the wheezing middle-manager doing abdominal crunches at the next bench: fat-free, zero-sugar girls, a bit of bling by Rolex and a big house by the sea. Dumb fuck dreams.

There is an order of magnitude between his generation and Laurent’s. His generation didn’t idolize the bourgeoisie. Whatever they claim, the working classes today all wish they’d been born on the right side of the tracks. In Lessines, the town where he grew up, the day was governed by the rhythm of the sirens at the local quarries. They despised the middle-class people from the other side of town. You didn’t drink with your boss. It was a law. In the bars, people talked of nothing but politics, class hatred nurtured a veritable proletarian aristocracy. People knew how to despise their boss. That’s all gone now, and with it the satisfaction of a job well done. There is no working-class consciousness anymore. The only thing that matters to them today is being just like their boss. Give a guy like Laurent power, and he wouldn’t want to force the rich to redistribute their wealth, he’d want to join their clubs. There has been a standardization of desire: they’re all free-market reactionaries. They’d make good cannon fodder.

Farther down the path, standing next to a bank of flowers, four park keepers are smoking with a man in a gray suit. A smiling, broad-shouldered Asian guy, a regular in the park who always wears a Stetson, is walking backward up a steep lawn. He always does this when he comes here, he never talks to anyone. A short-legged, long-haired gray dog runs around him in circles. Charles turns to his drinking buddy:

“Any idea why the Chinese do that?”

“Run up hills backward? Not a clue. Different cultures, isn’t it?”

“That’s true, it’s not something we’d normally do.”

Since spring, Laurent has been living on the abandoned railway track that runs through the park at the bottom of the hill. Not many of them sleep there, and the park keepers turn a blind eye as long as no one walks on the grass at night.

A woman hesitates near the bench where they are sitting as though she has lost her way. She is wearing a long red coat buttoned up the front, the sort of coat a little girl might wear; it accentuates her wizened face. She must be a schoolteacher. If she had more contact with adults, she wouldn’t be wearing a coat like that. Laurent raises a hand and waves when he spots her. She seems surprised at first, then recognizes him and comes over:

“Hello. How are things?”

“Cool. Care for a swig?” he says, proffering his cheap wine.

Instinctively, she takes a step back, as though he might force the bottle into her mouth.

“No, no, no thanks. I’m looking for a bar called Rosa Bonheur, do you know which way it is?”

“Always looking for something or other, you…”

Laurent is playing the lady-killer. Charles is embarrassed for him. For fuck’s sake, what are you thinking, expecting a clean, well-dressed woman to drink out of your bottle and listen to your shtick?

“If you’re looking for Rosa Bonheur, it’s simple, take that street there, go straight on, about five hundred yards. Did you ever find that guy, Subutex?”

“No. You never saw him again?”

“Nope … but I can take your details and if I hear anything, I’ll let you know…”

Laurent reels off his patter in the tone of a receptionist. He puffs out his chest, opens the zipper of his thick khaki gabardine, takes out a battered orange notepad, and, flashing a toothless grin, asks the lady to lend him a pen. He’s a pitiful sight when he tries to seem urbane. The lady in the red coat gives a slightly irritated pout and mechanically tugs at a hair between her eyes. Laurent carries on blathering as usual—when he finds himself a new audience, he doesn’t give up easily.

“Vernon got into a right mess because he was hanging out with the wrong tart … You see it a lot in newbies: too easygoing. If I’d seen him with Olga, I would have warned him to watch out. Everyone gets fooled. She seems nice enough at first, but if you hang out with her you end up facedown in the shit … It’s no life for women, living on the streets. And anyway, it’s easier for them to avoid it. If Olga had squeezed out two or three brats when she still could, she’d be entitled to loads of benefits, and let me tell you something, if you’re a single mother, they’ll find you fucking social housing. Guys like us, single men with no kids, we can drop dead … oh, but families, they’re sacred! Not her though, oh no, too much effort to crank out a kid … a useless bitch, that’s Olga. She has to do everything like a man … except when it comes to brawls, oh, she’s more than happy to throw the first punch, but the one who takes the punches is the guy who’s with her…”

“If you do see Vernon, tell him we’re looking for him, yeah? Tell him Émilie, Xavier, Patrice, Pamela, Lydia … we’re all looking for him. Tell him we’re worried … and that we have stuff to tell him, important stuff…”

“So, you gonna give me your number? And what did you say your name was?”

* * *

The woman in the red coat does not know how to say no. Her name is Émilie; reluctantly she mumbles her mobile phone number, then rushes off. She is a little wide in the hips, she moves unsteadily. “Where the fuck d’you know her from?” Charles says.

“There’re a whole bunch of them,” Laurent crows. “All looking for Vernon Subutex, but I’ve no idea where the bastard’s gone…”

“Who is this guy?”

“A loser. New guy. The sort you know can’t hack it. Too weak. Too delicate. I dunno where he’s gone, but it was obvious that the guy would never cut it, living on the street. At least ex-junkies have some experience with it, not him though … too la-di-da. He got in one brawl after another until some friend of his got beaten senseless and left for dead on the street. And then the guy up and disappears. His friends have been trying to track him down ever since…”

“She didn’t seem angry.”

“Oh, no, I don’t think they’re looking to give him a beating … they’re just a bunch of headbangers who’ve been hanging around the park looking for Subutex the last three days.”

“So what does he look like, this guy?”

“French, skinny, nice eyes, long hair, comes on like some faggotty rock star … He’s not much to look at, actually, but he’s a straight-up guy.”

The description sounds a lot like the guy up on the butte Bergeyre. Charles is wary. The guy was so sick, the old man thought he would croak right there on the bench. If he’s in hiding, he’s probably got good reason. We all have our secrets, and we all have our own way of dealing with them.

“So you’ve no idea why she’s looking for him, this woman?”

“Why are you so interested?”

“It’s not exactly common, a lady like that looking for a homeless guy…”

“Never trust women. They’re always hiding something … it’s probably something to do with death.”

“Death?”

“Women are always going on about how all they care about is kids … having kids, looking after kids, all that shit … and we’d like to believe them. But think about it. The only thing women are obsessed with is dead people. That’s their thing. They never forget. They want to avenge them, want to bury them, want to make sure they rest in peace, want people to honor their memory … women don’t believe in death. They just can’t bring themselves to. That’s the real difference between us and them.”

“I don’t know where you came up with that bullshit theory, but I suppose at least it’s original.”

“Think about it when you’re sleeping off the booze tonight. You’ll see. It makes sense.”

“That still doesn’t explain why she’s looking for this guy.”

“No. But I’m happy to shoot the breeze with a lady. I’m an obliging sort of guy. And I like women like her, timid, straitlaced, makes me want to give it to her, wham bam, thank you, ma’am…”

* * *

Charles leaves him to his lecherous ramblings. He is still surprised that the woman in the red coat deigned to talk to them. Charles looks like a tramp. People are reluctant to talk to him. But when he feels like talking to someone, he knows how to go about it. It’s like pigeons and crows; you have to regularly feed them little crumbs of attention. His approach is the same as the little old lady he used to run into around the neighborhood until last summer. She lived on the rue Belleville, and when she came out of her house at six o’clock, the pigeons recognized her. They would flock to her in huge numbers, in the air and on the ground, and follow her. She would scatter fistfuls of seeds and bread crumbs around the base of the trees along the avenue. Feeding pigeons is banned. To anyone who didn’t know what she was up to, the flights of birds synchronously swooping along the avenue Simon-Bolivar were very unsettling. One day, her kids put her in a home. Charles heard the news in the bar opposite the park gates. The old woman owned her apartment. The kids probably sensed the wind changing, the housing crisis coming, they wanted to sell up before the market crashed. Off to the slaughterhouse. She was a frisky old dame, had never touched a drink, the one pleasure of her dotage was feeding the pigeons when she went out for a walk … she was

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Vernon Subutex 2

Virginie Despentes

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved