- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

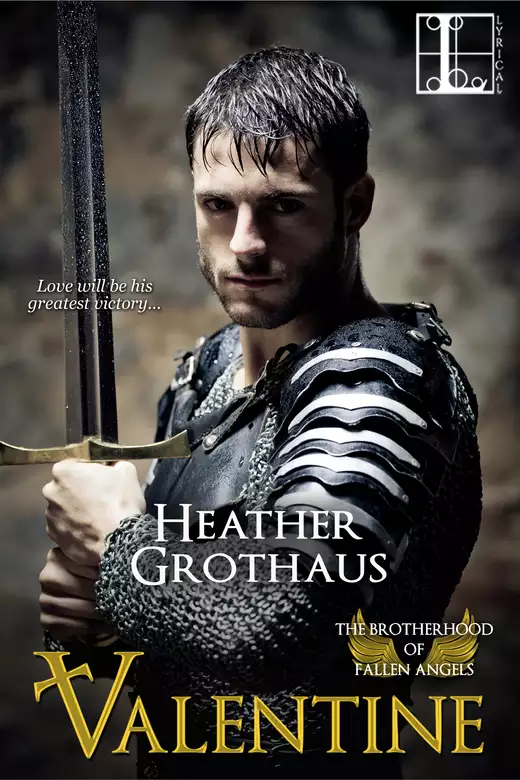

Synopsis

Introducing the Brotherhood of Fallen Angels—an epic new series set in the medieval Holy Land, where four heroic Crusaders find themselves caught in the crosshairs of revenge, devotion—and love… He’s a man of passion and principle. But would he kill for his convictions? That’s the question that has Valentine Alesander fighting for his innocence. He’s been accused, along with three other Brothers, of orchestrating the horrific siege at the Christian fortification of Chastellet. Could this fatefully-named Crusader be a lover, a fighter, and a traitor? One woman from his past is about to find out. Gorgeous, free-spirited Lady Mary Beckham has escaped her guardians in England to travel across the world—and find the notorious Valentine. Years ago, she was promised to him…and now she wants out of their marriage contract. Mary wants to wed another and requires Valentine’s blessing—until she discovers they share a tempestuous attraction. But with a vengeful band of sworn enemies at Valentine’s heels, is desire worth the risk of losing…everything?

Release date: June 23, 2015

Publisher: Lyrical Press

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Valentine

Heather Grothaus

It was the many persons she didn’t know whom she most loved to watch. She could give them her own pet names: Woolhead and Limpy Hip and Lady of Sausage. And she could create her own stories of their lives and personalities based on the small details she noticed from her observation point, high above the ground. Sometimes she had to watch for days to see some of her characters, but that suited Mary well enough. She had nothing else to do.

But her game had become more difficult the past several months, as the increase in Crusaders and pilgrims arriving and departing from the port of Beckhamshire caused temporary surges in the population of the town below. Mary would watch an individual for perhaps a fortnight, deciding on a name, a background, and then suddenly, with the ship departing to somewhere beyond the horizon, her character was gone and her story was dashed. This was particularly vexing with the soldiers, as they seemed to come and go from so many different lands, calling out with strange accents and wearing even stranger clothing.

Most vexing of all was that the majority of the fighting men would await their voyages in the lower levels of Beckham Hall, beneath Mary’s very feet, and yet she would never set eyes upon them while they were within her home.

“Well?” Agnes asked, her ever-present smile obvious in her voice. “Who’s out adventuring this eve?”

Mary glanced over her shoulder at her nurse, who was indeed smiling indulgently as she folded some freshly laundered linen at the table where Mary had taken her supper not even an hour before. Although Mary was a score and six years, Agnes still maintained her insistence that Lady Mary dine early, as she had since she was a child. Mary didn’t mind. After all, it left more time before bed to watch the comings and goings below as the soldiers attended to their duties.

“Yes, let’s see then,” Mary said, turning her attention back to the view below and scanning the milling crowd. “Grandfather Crumb has just come across the green, and he is brandishing some sort of pastry. A treat for a sweetheart, perhaps.”

“Likely a stale trencher to chuck at some lad who dares cross before him, I suspect,” Agnes chortled.

“Oh, no, I can’t believe that. He looks so kind—he’s always smiling.”

“He’s a curmudgeon. It’s a grimace.”

“Whose adventure is this any matter?”

Agnes laughed. “What of Lady of Sausage? It should be nigh hour for her to pack up her wares.”

“I’ve not seen her,” Mary admitted, scanning the villagers for the portly old woman and her long stick full of swinging meats. “Oh! But there’s Princess Lard.”

“Her mother must’ve already come through, then. Who’s the lucky prince today?”

“I can’t tell exactly, bent over the way he is. Perhaps the Merman.”

“For goodness, Lady Mary—likening that warty scavenger to a fantasy creature.”

“Princess Lard cannot resist his siren’s call,” Mary teased. “Perhaps he’s brung her a magic seashell.”

“More likely a penny,” Agnes muttered.

Mary grinned to herself and sighed again. Birds sang, and the air was sweet, indeed. Beckham Hall’s upper two floors—where Mary had lived her entire life—were as lonely as ever, but she smiled because they would not be lonely for very much longer.

Besides Agnes and a handful of servants, the official Lady of Beckham Hall had no friends, no family, and no companions of any sort. Hadn’t since she was a baby and her parents had been lost at sea. Mary’s father had been the warden of the Cinque Ports of England, governing the ingress and egress of ships for England’s southern shores and providing a substantial navy for the king. Upon his death, Beckham Hall—and Lady Mary’s guardianship—had fallen to the Crown and been held in that manner until a suitable replacement could be found for her father.

Lady Mary suspected that the king had used the lengthy search for a new warden as merely an excuse to more closely monitor the wealth going in and out of the town, and to use Beckham Hall for his own purposes; it was largely a garrison and storehouse for the endless river of fighting men. Her presence had been but an aside, and Mary assumed the king had quite forgotten about her existence until just before last Christmastime, when a ship of returning Crusaders had landed in the town and been forced to take shelter at Beckham Hall by a sudden and unusual ice storm.

That’s when she had met him—her future husband, her betrothed. He’d come up the stairs from the main floor—a passage that was usually barred from the inside to protect Lady Mary from the irascible ilk of the soldiers below—seeming intent on exploring the whole of the castle. He’d been quite shocked to find Mary before the hearth in her small private hall, tending to her handwork, and her heartbeat had increased at the sight of him. He’d worn a studded, dark leather hauberk with a cross burned into the hide, his weapon still on his hip, his flowing red hair cascading in waves from his high forehead.

“A thousand pardons, my lady,” he’d gasped with a low bow, and Mary’s heart had trilled in her chest. “I was unaware this floor was occupied. I shall leave you posthaste.”

“No,” she’d called, her voice shaking with fear and excitement. She’d glanced over her shoulder to the stairs, which led to the uppermost floor and Agnes’s sleeping chamber. “Please stay, if you’d care for company. I know I would.”

They had talked the moon into bed that night, and Mary had only crawled beneath her own covers when the sun sparkled through her icy window and Agnes had come in bearing the breakfast tray. For the next several days, they kept the same routine—Mary would unbar the door after Agnes was abed, and she and her brave knight would talk away the hours, speaking of her lonely childhood and deceased parents, of Beckham Hall and the surrounding village, and of his heroic escapades in the Holy Land. He even carried a fantastically embroidered coin purse hidden in an ingenious flap in his leather tunic, heavy with coin.

His company had departed within the week, and it was with bitter tears that Mary had watched her soldier go, waving at him from her window high above. Only after he was gone and Agnes would not ignore the heartbroken sobs of her ward did Mary confess her late-night activities. The nurse had been scandalized and outraged and questioned Mary mercilessly after her honor, but Mary answered honestly that her virtue was still intact, for not even a kiss had her lost hero bestowed upon her.

If she had been morose during all the lonely years of her residence at Beckham Hall, Mary soon became despondent. She didn’t look out her window. She’d lost all imagination for her game.

But then, on the first day of the new year, when Mary was sitting before her hearth alone, there came a rapping at the door to the lower floors. It was just past midnight. Hoping against hope, Mary had once more disregarded Agnes’s primary rule and dashed down the stairs to struggle with the bar. She flung open the door to find—

A strange soldier, dusted with his road travels and a light sprinkle of snow.

“Message from the Crown for Lady Mary Beckham,” the soldier had stated, thrusting a folded and sealed parchment at Mary.

She took it and secured the door once more before flying up the stairs to her chair before the hearth. Pulling the wax away with trembling fingers, she’d opened the message and read, her heart pounding in her chest.

Then she’d looked up from the royal decree and given a shout of laughter. The king had found his man, and apparently so had Mary, for she was to be wed that very year to her knight in burnished leather.

“You’d better come away now and prepare for your lessons with Father,” Agnes called, stirring Mary from her delightful reverie. Mary turned and regarded the nurse as she lifted her willow basket onto her substantial hip. “I’ll come back in an hour with your pudding and warm milk.”

“Yes, Agnes,” Mary said. And as she did as her nurse asked, Mary thought happily that the woman would soon find new purpose in caring for Mary’s own children, which would surely number more than the fingers on both her hands.

Perhaps her toes as well.

Mary was waiting in the tiny chapel tucked in a corner of the same floor as her private hall when Father Braund rushed in through the arched stone doorway. He gripped his leather-bound book in both hands and, after looking around at the hall behind him frantically, began to push the rounded wooden door closed. He apparently did not trust his eyes, for he opened the door again, leaned out, his head swiveling in either direction, and then shut the door firmly. He seemed to scan the closed door, as if looking for something.

Mary smiled at the usually calm priest’s odd behavior, and then her eyebrows rose as he seized the back of a plain wooden chair nearby and wedged it against the door, its back legs dropped securely into a gap in the wooden floorboards.

He’d been searching for a lock. But of course a private chapel would have no need for such secrecy, and Mary wondered why Beckham Hall’s priest suddenly did.

He spun around to face her at last, his flap of graying blond hair rising like a sail over his pate; and his eyes seemed to examine the very corners of the chapel, which was no more than twenty feet squared.

“Good evening, Father Braund,” Mary began. “Is something amiss?”

“Where is your nurse?” he whispered, his gaze flitting about the chamber.

“Well, I don’t know exactly,” Mary said, nonplussed.

“She isn’t here, is she?” the priest pressed, bending at the waist and peering beneath the benches as if he expected the portly woman to spring forth, shouting “Ah-ha!”

“No,” Mary said, half-laughing. “I don’t expect her until our hour is complete. She is insistent that I fully comply with my instruction before becoming a married woman, and I would wager she would rather spill a chamber pot across the floor than interrupt our lessons.”

The young priest shook his head, his flap of hair flopping, his eyes wide. Mary noticed he was gripping his leather book to his chest, as if clinging to the true cross itself. “No more lessons,” he said. “I’ve information of a much graver nature to impart to you this eve.”

Mary brightened. “I’ve completed all the lessons already?”

Again he shook his head, and his brows knit together in a pained expression. “You may not get the chance to put them into practice.”

The first inklings of concern tickled at the nape of Mary’s neck. “What do you mean?”

Father Braund swallowed and his eyes flicked down to the book in his hand. “Come,” he said at last, scurrying to a tall, shallow side table against one of the walls. He set down his book as Mary appeared at his side.

“As you know, I must compile a document of your birth and lineage, and that of your parents’, to be recorded in preparation for your marriage. Because your betrothed would gain not only your hand and Beckham Hall but also a noble position within the king’s court, it is imperative that records of your pedigree be complete, for they shall be thoroughly examined by the king’s advisers before your wedding takes place in the autumn.”

“Yes,” Mary said, “but I don’t see how that could possibly give you cause for such alarm. My father’s lineage is well documented here, where he and his predecessors were born for hundreds of years. And my mother’s family is well known as one most loyal, even as long ago as to William. I was their only child, of that there can be no question.”

“No, no—no questioning any of that at all,” the priest agreed, still speaking in a raspy voice, as if he feared they would be overheard through the thick stone walls. “It’s what was recorded after your birth that is so troubling.”

Mary frowned. “After my birth?”

“Your baptism!” the priest hissed ominously.

Mary waited for further clarification from the agitated priest, but none came. “I don’t understand. I was born unexpectedly at sea, on one of my father’s ships, during a storm, and so the baptism was performed at a place other than Beckham Hall. But Father de Moy found nothing out of order when we at last returned home, obviously, else he would have performed the ceremony again. And he certainly never mentioned to me that anything was amiss before he died last year.”

“You did receive the full sacrament, and it was recorded precisely,” the priest whispered, and then leaned closer to Mary’s face. “Along with another important agreement, documented here in Father de Moy’s own hand.” He opened the book, rifling through pages for a moment before spreading both halves flat and pushing the large tome toward her. “You can’t marry your knight, my lady.”

Mary was becoming worried, and that emotion wanted to manifest itself as anger. “Why ever not?” she demanded, taking hold of the book’s edges and tiptoeing to lean close to the tiny scrawls, her eyes scanning the jagged marks made by Beckham Hall’s longtime—and now deceased—priest.

Her eyes skipped along the unbelievable information just as the priest whispered at her shoulder.

“You’re already married.”

Mary read the lines scratched in the book perhaps fifty times before she straightened and looked at Father Braund. “Well,” she said, “obviously I was promised in marriage shortly after my birth. But this document cannot be binding as the man has never come for me. All we need do is send a message to this family and demand that the agreement be annulled. Surely he has already married by now, or perhaps he is long dead and that is the reason we have had no word of him. His family has simply forgotten all about me.”

The priest shook his head. “He’s not dead.”

“My goodness, how could you possibly know that?” Mary peered at the book again. “I realize I’m rather sheltered here, but I’ve not heard mention of any Spaniard—this . . . this Valentine Alesander.” She straightened.

Father Braund swallowed.

“How do you know, then?” she demanded. “Tell me, because I will not have this man, whoever, wherever he is. I refuse to be married to him. I don’t want him!”

“Well, I should hope not,” the priest said. “He’s a criminal wanted by the Crown.”

“A criminal?” Mary shrieked.

“Shh!” Father Braund clutched at her arm and looked around the chapel fearfully before returning his gaze to her and continuing in a whisper. “A group of pilgrims returned from the Holy Land only a fortnight ago, bringing further word about the king of Jerusalem’s defeat at his mighty fortress. It’s been determined that the siege was enabled by a small group of traitors in the king’s own company, and that this Alesander was among the betrayers. Four men in total—Gerard, Hailsworth, Berg, and your Alesander—all on the run, and now sought by every bounty hunter and Christian ruler the world over.”

“He’s not my Alesander!” Mary hissed. She collapsed on a bench and threw a hand over her eyes. “No! No, no, no! It was all so perfect!” After a moment she dropped her hand and turned on the bench to face Father Braund. “Surely the king would see this farce terminated. He would not hold me to such an evil agreement.”

“There’s more,” the priest admitted. “Alesander’s family was once wealthy nobles—some of the most respected and powerful in the kingdom of Aragon. But there was a rebellion, and this man—your husband—double-crossed his family and absconded with a vast portion of their wealth. It is rumored he murdered at least one of them. His kin have been searching for him for years. If they—or he—should discover his connection to you, and that you are soon to wed another, it is completely conceivable that they could come looking for you and insist that the match be honored for the dowry to replace what was lost to them, and Alesander could then lay claim to Beckham Hall.” Father Braund paused, seeming to consider. “That is, of course, if he was not hanged first, leaving you a penniless widow with no home.”

“He is not . . . my . . . husband!” Mary insisted. Her stomach knotted and her mind raced. If her betrothed—a man profoundly loyal to the Christian king of Jerusalem, who had nearly lost his own life in the Holy Land protecting King Baldwin—found out about this ancient agreement with one of the traitors, he would absolutely call off the wedding. Perhaps he would even be granted Beckham Hall for his trouble and embarrassment.

He could never find out. Never.

Mary looked up at Father Braund. “What can I do?”

The priest gave a deep sigh. “There is only one possible solution, and it is highly unlikely you would succeed.”

“I don’t care. I must try.”

The priest nodded and then came to sit next to Mary on the bench. “Through my religious connections, I have heard of an abbey that has taken on the task of gleaning information that would bring justice to the four traitors.” He reached into the folds of his robe and pulled out an object that he kept clenched in his hand. “You must visit that abbey and enter into a confessional with a red curtain. Once there, give the priest this.”

He held out his hand; lying in the center of his palm was a single gold coin.

Mary picked it up with a thumb and forefinger, noting the rough edges and Latin inscription.

Father Braund continued. “Tell the priest—Father Victor—tell him everything. Tell him the name of the man you are looking for. If there is any help to be had, he will be the one to provide it. We are fortunate that your wedding is yet months away—it is common for those engaged to inter themselves at a religious house for a period of intense instruction. It should raise no suspicion with your betrothed, but we must not reveal your exact destination. To anyone. Not even to Agnes.”

“Then I don’t see that this is so very difficult a task after all,” Mary said. “I only have need of a conveyance to carry me to whichever part of England the abbey is in, and—”

“Not England.”

Mary paused. “Scotland?”

Father Braund shook his head. “Austria. On the Danube River.”

“Austria?” Mary shrieked. “How am I to get to Austria? I’ve never even been to London!”

Father Braund stared at her for a moment. “Are you ready for a real adventure, Lady Mary?”

Valentine Alesander pretended to peruse the wares at the market stall as he circled around in pursuit of his quarry. He picked up a strand of garlic, seemed to consider it as he gave the stall’s proprietor a sage nod of admiration, and then returned it to the pile. Two more slow, sidling steps to the right to the next stall, which offered a selection of cheeses.

The woman was stopped, considering a large wedge wrapped in cloth with great concentration before putting it down and picking up another, smaller piece. Eldest daughter; many mouths, little coin. Valentine leaned his left forearm along the stall’s half wall.

“Good day,” he said. “Beautiful weather for marketing, yes?”

The woman glanced up with a frown, and then her face softened as her eyes took in Valentine’s person. Her lips and fingertips were stained berry pink. Fruiter’s daughter.

“Indeed,” she replied. “God is admiring his creation.”

“As am I,” Valentine replied, taking in the young woman’s abundant curves. Perhaps eighteen.

Her brow wrinkled. Steady suitor, arranged marriage. “Well, certainly. It is your duty always to point to his wondrous deeds. Everyone appreciates your dedication.”

“Is that so?” he asked, taking a half step closer. “Perhaps you would like to express your appreciation in a more . . . personal manner?”

“I—” the woman started, her frown increasing into an expression of distaste. “I must go. Good day, Brother.”

“Wait,” he called after her, straightening from the stall, but she had already fled through the milling crowd of the village. “Damn.”

“I do believe you are losing your touch, Brother Valentine,” the deep voice said from behind him. Valentine turned to see Roman Berg, a bouquet of long loaves beneath one massive arm, his voluminous robes making the man seem twice as wide as he already was.

“I am no losing my touch—it is only this damned gown,” Valentine muttered, jerking at the brown cowl sagging against his chest.

“Certainly it is.” Roman chuckled. “The women of Melk would not risk hell by dallying with a man under holy orders—not even one with your pretty lashes. And Victor has warned you about your forwardness with the women villagers.”

“Bah, Victor. I hate this place.” Valentine turned and joined Roman as the man began to walk back through the village.

“ ’Tis better than a Damascene dungeon.”

“I will only concede that the climate is milder,” he answered. “In truth, we are as trapped here as if we were still beneath Saladin’s hand.”

“Perhaps,” Roman said. “But I still prefer this locale. And that we are not dead. Any matter, something to distract you for a bit—Stan says a large group of pilgrims has come to Melk today. I know not from which direction they hail, but perhaps they carry some bit of news. I’ve not seen Victor since Lauds—which you were absent from. Again.”

“I am pretending to be a monk, Roman. Pretending,” Valentine enunciated. “I am glad you find some enjoyment in the role, but me? Pfft!” He threw up his hands and noticed crossly how the movement caused the villagers he and Roman passed to bow their heads.

Roman smiled and raised his right hand to make the sign of the cross in the air before them. “God’s blessing upon you.”

Valentine only smiled stiffly until they had passed the pious group. “I suspect Victor would have us all become monks in truth!” he continued his rail. “It is Brother This and Brother That all the day—and that is when we are even allowed to speak! But do you know the worst part?” he demanded of his friend.

“No women?” Roman guessed.

“No women,” Valentine said. “No a maid, a laundress—nothing! Only men!”

“Melk is an abbey of monks,” Roman pointed out. “I don’t know why you do this to yourself every time. Perhaps you should stop coming to the market.”

“And go completely mad?” Valentine kicked at a rock in his path, very aware that the action was childish. “I hate this place.”

“Well, one thing is certain—there is nowhere else for us to go in the foreseeable future, lest we yearn for stretched necks. The bounties on our heads are such that every man with a sword and a too-light purse is looking for us.”

Roman came to a halt in the dirt road, having reached the end of the market and the fork that led either deeper into the village or up the long and narrow path to the monstrous abbey on the cliff overlooking the Danube River. Valentine paused to listen to his friend.

“I know you are unhappy here. But there is nothing to be done about it. I for one am not sorry that you came upon Chastellet, else Stan, Adrian, and I would all likely be dead.”

The giant’s words kicked at Valentine’s conscience. “I am no sorry for that either, my friend. Forgive me. I am no myself today.”

“I think you are very much yourself.” Roman grinned and clapped Valentine on the shoulder as he nodded past it pointedly. “Cheer, Brother—it seems as though a lovely pilgrim has need of religious assistance. And since I must return to Lou in the mews, I shall leave you to her. And I shall not tell Victor. See you at supper.” Roman stepped away with a wave and then turned up the path toward Melk.

“Tomorrow is my birthday,” Valentine said to Roman’s back when his friend was far enough away that he could not overhear. He sighed and turned to look down the path where Roman had indicated.

She approached swiftly, glancing about her, but Valentine could not tell if she was wary of someone following her or disconcerted by her surroundings. Her gown was clearly English, simple but well made. Her kirtle was a drab brown with gold braid trim and belt, revealing a plain, creamy underdress with wide bell sleeves. Her hair was the color of chestnuts, hanging long over one shoulder and twisted with ribbons. Her complexion was the epitome of an English lady of sheltered and privileged life, like the petals of a peony, a dusting of pink across her cheeks. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...