- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

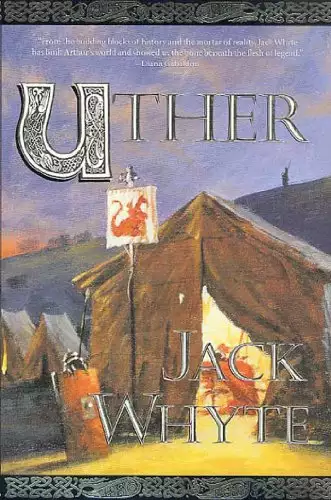

With Uther, Jack Whyte, author of the richly praised Camulod Chronicles, has given us a portrait of Uther Pendragon, Merlyn's shadow--his boyhood companion and closest friend. And the man who would sire the King of the Britons.

From the trials of boyhood to the new cloak of adult responsibility, we see Uther with fresh eyes. He will travel the length of the land, have adventures, and, through fate or tragedy, fall in love with the one woman he must not have. Uther is a compelling love story and, like the other books in the Camulod Chronicles, a version of the legend that is more realistic than anything that has been available to readers before.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: December 9, 2001

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 624

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Uther

Jack Whyte

BOOK ONE

CHILDHOOD

Greetings, my dear daughter:

I have been thinking about writing to you for weeks now, making up snippets of things to tell you and composing entire passages in my mind as I go about my household tasks, but I sit down to it only now, almost afraid that I might be too late, and unpleasantly surprised, all at once, by how quickly time has passed since I last wrote! Last night, as we sat together before going to bed, staring into the fire, your father remarked that the leaves have begun to turn yellow, and pointed out that, before we know it, it will be winter and both you and Picus's wife Enid will be facing confinement and childbirth. That shocked me profoundly, because my immediate reaction was to chide him for exaggerating, until I realized that he was not exaggerating at all. It seems like only yesterday that I was writing to you, describing my excitement over the newly delivered tidings that you were with child and would be giving us a grandson or a granddaughter at the start of the New Year. And now, so soon, your term is more than half elapsed! And that, of course, means that you have been a wife, a married woman and the mistress of your own household, for almost two-thirds of a year, and for that entire time I have not set eyes upon you. How must you have changed in appearance, from the merry-faced, laughing daughter whom your father and I loved so much and in whom we took such pride, knowing how close we had approached to losing you completely when you were tiny.

I was interrupted, between writing those last words and these, and a full day has elapsed in the interim. Writing is a slow and sometimes painful process, for the hand is unused to clutching a stylusfor so long a time. And yet Publius writes every day, for long periods each time, so I must believe that the pain wears off with usage. I do hope you are thriving and that your pregnancy is causing you no great discomfort. As you know, I went through the entire process four times, and I had not a speck of trouble with you or any of your sisters at any time, except for the anguish (merely occasional, thanks to your father) of having failed to produce a son to carry on the name of Varrus. It is too late for that, now, and so the name will die, I fear, with my dear Publius, for I know of no other males of the family Varrus now alive. God forbid, however, that anything of that kind should occur for many, many years. In the meantime, your father's pride and manliness, his heritage and all his nobility will live on in your children, and although their name will not be Varrus, dren, and although their name will not be Varrus, yet their mother's blood will make them both Varrus and Britannicus, and they will reflect, in their natures, all the elements that made their mother's father the fine man that he is. But I was speaking of your pregnancy and wondering how you are bearing it. Some women--most of them, God be thanked!--take the condition in their stride, dealing with it daily in the passage of time and suffering no ill from it at all. Others thrive visibly on the condition, blooming while they carry the child and achieving a degree of beauty they seldom recapture in fallow times. And then again, there are the others, poor creatures who cannot sustain the role that has been thrust upon them and who suffer untold agonies and endless sickness through their entire term of carrying. These are the ones who, all too often, have Harpies awaiting their delivery and who too frequently die in childbirth. I know that you are of one or the other of the first two groups, my dear Veronica, for had you shown any indications of belonging to the third, I should have heard of it long since, and I would be there with you now, instead of sitting here writingyou this long and rambling letter. Your father is calling me.

Well! Another day gone by. I begin to believe that, once interrupted, it becomes impossible to resume writing the same day. Yesterday, when I went to your father's call, I found that one of the young stable boys had been kicked by a horse. He must have been careless in some way, but we will never know, because he died without regaining his senses. He was only eight years old, and your father was very angry that the child had been left alone to do a man's work. We had a noisy and exciting evening of heated arguments and cold anger as he tried to discover the truth of what happened from a number of people who really did not know. Generally, however, your father is well, in radiant health and strong as a man half his age. He continues to spend the greatest portion of his time in his old forge, banging away at white hot metal, all the while in danger of suffocating from smoke and noxious fumes. But he is happiest when he is there, so what can I, a mere woman, do to dissuade him? It makes me smile to recall it, but there was a time when I thought he must regret that I had so little interest in his forge and what he did in there. I was wrong. I have learned to believe that your father is perfectly happy to have me stay in my place, here in our home, and allow him to do as he must in his place of work. And when he comes home to me, as he always does, I never doubt his gladness at setting eyes on me. Now that is a gift I wish I could bestow on you, daughter. But I cannot. The only person who can grant that gift to you is your own man, Uric, and the only means you have of influencing him to do that is to manage his home, share in his dreams, encourage his visions, and love him.

It is a beautiful day, here, and the sky is flushing pink with the promise of a wondrous sunset. It is strange to think you might not be able to see it where you are, among the hills. It might be rainingthere, or foggy with low clouds. Well, child, now that you are a child no longer, know that we love you none the less, your father and I. Carry your own child proudly and with gladness, whether it be boy or girl, and never fear about your ability to bear men-children for your husband. I produced only girls, but the women of our family have always been breeders of strong men, so perhaps I was an aberration. You, I am convinced, will bring forth boys, and if Uric truly is of Ullic's blood, he will contribute to that bringing forth. I will not insult you by asking you if you would come home to have your child. I know your place is there in your husband's land, as Enid's is here, in her husband's, even land, as Enid's is here, in her husband's, even though Picus is away at war. I remind God every day and night, in my prayers, to keep all of you strong and healthy and safe above all God bless you, child, you are in my mind and my heart at all times.

Your loving mother, LV

Dear Mother:

I overheard Uncullic this morning telling Uric that he intends to ride by Camulod on his way to wherever he is going in the week ahead. Thus, mindful of the enormous pile of papyrus you sent me recently, hinting that should I ever think to write to you I should not lack the means of doing so, I thought to take this opportunity to write and let you know that I am well and having no trouble at all with the burden I am carrying. The grandchild I will bring to you is all male. His strength and his lack of delicacy and consideration tell me that he could be nothing else. But he has been well behaved, generally speaking, and I am quite sure he will cause me no insurmountable difficulty when it comes time to bring him out to face the world in which he must live. My dearest hope is that you and my father are both as healthy as I feel, because if you are, I should rejoice. And on that topic of rejoicing, we are caughtup in the end of the year celebrations, although Samhain, the winter solstice, has already passed long since and the days are beginning to lengthen. Now that I am living among the Cambrians and have made their way of life my own, I am often astonished to see just how different their customs and celebrations are from ours. I can clearly remember sitting listening to Bishop Alaric on one bright, lovely summer's afternoon several years ago, as he told us about the various ways in which the communities in the small territories wherein we live have come to use different ceremonies and rituals to celebrate the same important events throughout the year. Events like the solstices, when the sun reaches the limits of its flight and sets off again upon its return course. But even our beloved Bishop could not convey the scope of such differences.

I know that our own tradition, in Camulod, is rooted in our Roman past. But the Celtic clans celebrate Samhain when we celebrate Saturnalia. I had heard the name before, and I recall that as a child, I passed the Samhain festival with you and my father in two small communities that I remember as lying to the south and west of Camulod. Neither of those two occasions, however, bears any slight resemblance to what goes on here in Cambria at this time of the year. And then, recently, within those regions and among those clans where Christianity has spread, the rituals and the events we celebrate are changing every year. But all that matters is that we celebrate. It matters not what name we give to the celebration, or how we observe it. The people are glad of the opportunity to celebrate something, anything, and they are ready for the pleasure. The crops are safely in, the fields are all prepared for winter, and the lagging year is drawing to a close, amid the hope brought on by lengthening evenings and small, unseen promises of greener, warmer days to come in a year that is entirely new.

Not all of us in King Ullic's household are celebratingthis year, however. There is one unfortunate woman here whose heart is sore and heavy, and where I, in similar circumstances, would be blessed and strengthened in time of need by my beloved husband, she lacks that source of strength and comfort. She has a husband, but he is a very different kind of man from mine. Her name is Tamara, and her husband, whose name is Leir, is a Druid. He is also related to Uncullic, a cousin of some kind. I do not know the full relationship, but I have been told that his grandfather and Uncullic's father were first cousins, born to the brother and sister of the first Pendragon King of the Federation, another Ullic, as you know: Ullic Green Eye, who ruled almost a hundred years ago. I wonder if that means he had only one eye? Or one green eye and one of another colour? But that cannot be, since all these Cambrian kings must be physically perfect. I must find someone to ask about that.

I stopped when I had written those last words, and walked away from my table, because I found myself writing nonsense. And my fingers were starting to cramp. They are blackened to the first knuckle with ink, too. Unlike you, however, I have been able to come back to the task the same day, for less than an hour has gone by since I stopped writing. I set out to tell you about poor Tamara and her trouble. I have come to know her quite well, these past few months, because like me, she was with child, her first. Alas, no longer. Tamara is very small, a tiny wisp of a woman, but her child, a boy, was enormous, so large, in fact, that there were whisperings of twins among the elderwives here, before her time arrived. Twin births are not looked upon with favor among the Celtic peoples, I have learned, and this is particularly so among King Ullic's clans here in Cambria.

As it turned out, however, and despite what the elderwives might mutter during their shadowy gatherings, Tamara was unfortunate in that she bore notwins. Instead, she bore one single, monstrous lump of a boy who tore her cruelly while forcing his way, a month and more before his time, out of her small body. That was four days ago, and poor Tamara remains abed, too weak even to sit upright. My fear is that she will not recover at all, because I am already astounded that she has survived this long. Mother, she lost so much blood! I knew it was going badly with her. Anyone with ears knew that. And I wanted to do something to assist her in her terrible pain and loneliness, although I know not what that. something might have been, but the elderwives kept me from the chamber, so that I could only listen to her screams and moans growing more piteous as she herself grew weaker. It lasted more than an entire day before the child was finally born, deformed, his head completely flattened on one side by some hideous mischance. In the normal way of things in this land, which can be frighteningly savage, the child would have been stifled at birth because of his deformity, but for some reason, concerning which it seems to me everyone is being very secretive, the elderwives were loath to kill him before consulting with his father, the Druid Leir.

Leir came, eventually, although he had not cared to show his face during poor Tamara's travail, and he spent a long time alone with the child, who was his firstborn son. Everyone assumed that, being a Druid, he must be praying for the infant, but then when he emerged from the room, he refused to let them kill the boy. I know, because I have been told, that the elderwives were much surprised by this, and greatly at a loss. It would appear, however, that Leir has great power, sufficiently great, in fact, to. flout established custom, although I know not upon what it is based. I do know that no one dared gainsay the man. Uncullic might have, and many here expected him to do so, but for some reason, as King, Ullic chose to ignore the matter, and so the child still lives. Leir, unsurprisingly to me, has laid all the blame forthe entire misfortune upon the unfortunate woman Tamara. It is no fault of his, apparently, that there were problems with the birthing of his child; no deficiency could possibly apply where he and his are concerned. It is the woman and her evil, vicious ways that brought the child to grief. The obnoxious creature, Druid though he is, has ignored Tamara completely since the confinement began. And, if truth be known, I think it possible that he has ignored her much longer than that. She is disconsolate, of course, but fortunately she is also far too weak to really be aware of what goes on about her. There is something loathsome about the Druid, and my flesh chills whenever he approaches me. He has a slight cast in one eye and a formless vacancy in his expression.

There is a word that Uncle Caius likes to use to convey the notion of utter emptiness: it is vacuous! I asked him once about it, and he told me it means filled with empty nothingness. It is the perfect word for what I sometimes see in this Leir. There are times when, looking at his face, I would swear he is demented. There are very few who will talk about him at all, however, and that really surprises me, for Uric's people are a talkative clan, much given to minding other people's ways. Those few who will talk of Leir do so with caution and then have nothing really substantial to say.

After four days, it now appears the child, who has been named Carthac, will live, despite the wishes of all who hoped that he would die. Equally, it appears that his mother Tamara will die, despite the best wishes of her many friends.

I am not at all afraid that the tragedy of what has happened to her might have any effect upon, or any similarity to, what will happen to me when my time comes, within the next few weeks. Tamara's case was awful, but it was unique, too, bred of her own tiny stature and the leviathan girth, weight and sheer size of the monstrous child she bore. I am much largerthan she was, and my child is that much smaller. Besides, I have a husband in whose love I float like rose petals upon water, and he has a father who has known and loved me all my life. No harm will come to me here, and my child will emerge into the love and warmth of all his father's relatives, and he will thrive therein until he has the additional good fortune to encounter, at a very early age, the love of his mother's family, too. We have decided that his name will be Uther.

Kiss my father for me. I will write to you again, as soon as I may after your grandson is born. I hope all is as well with Enid as it is with me.

Your loving daughter, Veronica

I

Even when he was a small boy, no more than four or five years old, Uther Pendragon knew that everyone around him believed that his mother, Veronica, was different from everyone else. They even had a special name for her: "the Away One." He was very young when he first learned who they were talking about when they used it, and it took him many more years to understand what they meant by it. After all, his mother had never been away from him. Veronica was and had always been a constant in his young life, along with his nurse, Rebecca, who had come to Cambria with his mother. Those two women, between them, had made their presence absolute in everything young Uther did during his earliest years, while he was yet too young for his presence to be noteworthy to others. In the beginning, there were only those two.

One of the very first newcomers to join this tiny group of intimates was a woman called Henna, who had been assigned by Uther's grandfather, King Ullic Pendragon, to cook for the newcomers at the very outset of Veronica's life in Ullic's stronghold, eight months and more before Uther was born. Henna had quickly warmed to the King's new daughter-in-law, despite the younger woman's alien upbringing and Outlandish behaviour, so that, for one reason and another, she had never stopped cooking for her new charges and had been completely absorbed into their new life as a married couple. By the time Uther grew old enough to look about him and observe his surroundings, Henna the cook was a fixture of the household in which he lived. And after he had learned to run and to talk, he quickly learned that if he ran and talked to Henna, she would give him wondrous things to eat.

Henna was the first person Uther ever heard using the term "the Away One" to describe his mother, andalthough he did not know then who the cook was talking about, he knew that there was no slight or disparagement intended in the strange-sounding name. Young and inarticulate as he was, he understood perfectly that the Away One was a woman, unfortunate or afflicted in some way. And as he grew older, and he heard the name repeated more and more often by people who thought he was too young to be listening, he soon came to understand that this mysterious woman was different in some important respect from "normal" people. He knew that all of the women who gathered in Henna's kitchen liked the Away One and held her in high regard--that was plain in the tone of their voices when they spoke of her--and he knew, too, that they all felt sorry for her in some way, but for a very long time he was unable to discover the woman's identity.

On one occasion, frustrated by something particular that he had overheard, he even asked his mother who the Away One was, but Veronica merely looked strangely at him, her face blank with incomprehension. When he repeated the question, articulating it very slowly and precisely, she frowned in exasperation and he quickly began to talk about something else, as though he had never asked that question in the first place.

Despite having broached the question with his mother, however, he had never been even slightly tempted to ask Henna or any of her friends, because he knew that would have warned them that he was listening when they talked and they would have been more careful from then on, depriving him of his richest source of information and gossip. And so for long months he merely listened very carefully and tried to work out the secret of the Away One's identity by himself, looking more and more analytically, as time went by, at each of the women with whom he came into contact in the normal course of life. He knew that there would have to be something about this particular woman that set her noticeably apart and gave others the impression that she was never quite fully among them--that her interestsheld no commonality with theirs, that she was someone who was not wholly there.

He floundered in ignorance until the day when, in the middle of talking about the mysterious woman, Henna suddenly hissed, "Shush! Here she comes," and his mother walked into the kitchen. Uther was stunned by the swiftness with which the truth dawned upon him then, because it was immediately obvious that Veronica met all of his carefully defined criteria. His mother did not associate with Henna and her people in any capacity other than that of the mistress of the household dealing with her servants, issuing commands, expressing her wishes and expectations, and occasionally complaining and insisting upon higher standards in one thing or another; yet it was plain that they all liked her and that they respected her integrity and natural sense of justice, despite the fact that she held herself somewhat aloof and apart from all of them. Uther had developed the ability to reason by the time he was five and now, having discovered at six years of age who the Away One was, he felt immensely proud of himself, as though he had solved the entire mystery all on his own.

His pride, however, was short-lived, because within the month he overheard another conversation in which a newcomer to Ullic's settlement, a weaver woman called Gyndrel, asked Henna why they called the Mistress the Away One. Henna, a woman who loved to answer a question with a question, promptly asked Gyndrel why she thought they would call her that. Gyndrel's first response was that the name must have come from Veronica's obviously foreign background, from the fact that she came from someplace away from Cambria, but Henna snorted with disgust almost before the words were fully out of Gyndrel's mouth. Veronica, she pointed out, might have begun her life as an Outlander, but she was now the wife of the King's eldest son, and no one in the entire Pendragon Federation would dare to insult or defame her nowadays by hinting that she might be anything less than acceptable. Henna then told the woman, her words dripping with disdain, to stopdrivelling and use her mind for a moment.

Sitting on the far side of the fire from the women, concealed from their direct view by a pile of firewood, Uther nodded smugly to himself as Gyndrel eventually answered with all the plausible reasons he would have given in her place. But his head jerked up in shock when Henna dismissed all of them with a scornful laugh.

Nah, she scoffed, pulling her shawl tightly about her shoulders and shifting her large buttocks in search of more comfort. When Gyndrel grew more familiar with this family and what went on under this roof, she would soon learn that the Away One meant simply what it said, and that the Mistress was all too often far away in a place of her own within her own head, far from Cambria.

That dose of information, unexpected as it was, gave young Uther much more to think about than he had ever had before, and he began to watch his mother closely, examining her behaviour for any sign of these "absences." But of course it was useless to attempt anything of the kind, because his mother's behaviour was no whit different than it had ever been, and he had never seen anything strange about it before. Nevertheless, he remained permanently alert after that for signs of awayness in her.

After that day, too, he took especial pains to safeguard and protect his virtual invisibility in the kitchen while the women were gossiping, removing himself from view, if not actually hiding, from time to time whenever the conversation promised to be especially enlightening, and he never failed to keep one ear mentally cocked for any mention of his mother's "other" name. He learned much, over the course of the ensuing four years, and he began to recognize the "away" intervals in his mother's behaviour, but he never did learn anything in the kitchens about the underlying cause of Veronica's supposedly strange behaviour and he eventually became convinced that Henna herself did notknow the truth, no matter how hard she tried to appear all-knowing.

It would be years before Uther was able to piece together a semblance of the "truth" that he could eventually accept, and the first plausible explanation that he heard came from a conversation between his father and his mother's father, Publius Varrus. It took place in Camulod, in the early autumn of a year in which Uric had brought his wife to visit her parents Publius and Luceiia Varrus, to collect his son, who had spent the entire summer in his grandparents' home with his "twin" cousin, Caius Merlyn Britannicus. The two boys had been born within hours of each other on the same day, albeit miles apart, one of them in Cambria and the other in Camulod. They were very close to each other, in blood if not in actual temperament, and they had been the best of friends ever since they had grown old enough to recognize each other. Caius's father, Picus Britannicus, had once been a cavalry commander--a full legate--in the Roman legions under the great Flavius Stilicho, Imperial Regent and Commander-in-Chief of the boy emperor Honorius. When his wife, Enid, a sister to King Ullic, was killed by a madman, shortly after giving birth to their only son, Picus's aunt Luceiia, Uther's own grandmother, had adopted the infant Caius as her own charge in the ongoing absence of his father.

When the two boys were very small, barely able to walk and run, Uther's mother Veronica had insisted that they spend as much time as was possible in each other's company, for both their sakes, and for the good of the family, and so it had become normal for Uther to spend much of each summer down in Camulod, and then for Caius--or Cay, as he had come to be known by his friends--to return with him to Cambria for much of the winter.

On this particular afternoon, Uther was once again playing the role of invisible listener, his eavesdropping skills long practiced and sharpened by his years of hiding in Henna's kitchen. It was a dismal, rainy day, andthe boys were playing indoors in the old Villa Britannicus, once the ancestral home of Caius Britannicus, Caius Merlyn's grandfather, but now used as quarters for visiting guests, since the Britannicus Varrus family had moved up to live in the new fort at the top of the hill, less than a mile away.

Uther had been hiding from Cay and his other friends, well concealed behind a curtain in his grandfather's favorite room. When he heard the sounds of approaching footsteps, he remained utterly still, believing it was his companions come looking for him. When he heard his grandfather Publius begin to speak, however, he realized his error and began to emerge from his hiding place, but almost immediately, perhaps by force of habit, he hesitated.

Uther's father had followed Publius into the room and his grandfather asked his first question without preamble. It was suddenly too late for Uther to emerge at all. And so he remained where he was, and listened.

"You can tell me to mind my own business if you wish, but there's something wrong between you and Veronica, isn't there?"

Uther stood motionless, holding his breath as he waited to hear his father's response. The silence that followed his grandfather's question seemed to last for an age, however, and then Uther heard the sound of slow footsteps and the scraping of wood on stone as someone moved a chair.

"Has she said anything to you?" his father asked.

"No, she has not ... not to me, nor to her mother ... but neither one of us is stupid, Uric, and Veronica is not a facile liar, even when she keeps silent. The trouble's not ours, for all that we love our daughter ... it's yours and hers. A daughter and a wife are two distinct and very different creatures, coexisting in a single woman. But, as I said, if you don't wish to talk about it, I'll respect that."

Another long silence stretched out and was shattered by the brazen clash of a gong, its unexpectedness making Uther jump, so that for a moment he was afraid hemight have betrayed himself. Nothing happened, however, and as his heartbeat began to slow again, he heard another voice, this one from the far side of the room.

"Master Varrus, what may I bring you?"

"Ah, Gallo, bring us something to drink, please. Something cold."

Gallo must have retired immediately, because the silence resumed, and then his father spoke again.

"I don't really know what to tell you, Publius. Something definitely is wrong, as you say, and it has been wrong for a long, long time. There's a part of me that thinks it understands, but even so, it doesn't really make sense, even to me, so how can I explain it to you?"

It was some time before his father spoke again.

"Not that we are unhappy, you know ... it's simply that ... well, we sleep together and behave as man and wife, but I know--" Uric Pendragon broke off, and then continued in a rush. "She won't have any more children. None, Publius. And I don't mean she is incapable of having any more. I mean she will not have them. Doesn't want them, won't hear talk of them. She takes ... she takes medicaments and nostrums to guard against becoming pregnant. Gets them from some of the old women who live in the countryside beyond our settlement, the ones who are supposed to be the priestesses of the Old Goddess."

"The Old Goddess? You mean the Moon Goddess?"

"Aye, the greatest of all our gods and goddesses. Rhiannon, we call her. She is very real and very present, out there among the people of the mountains and the forests."

"Why on earth would she go to such lengths to avoid having children? That does not sound like the Veronica I know. All she ever dreamed of, as a girl, was having a brood of children of her own. You must have--" Varrus broke off and cleared his throat. "Damnation, it's diffi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...