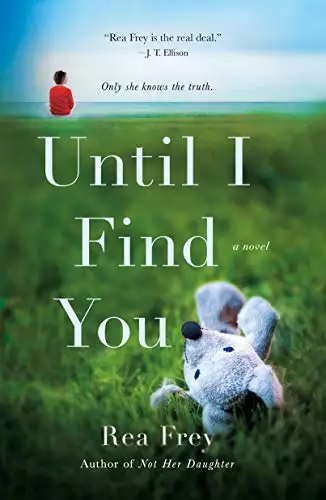

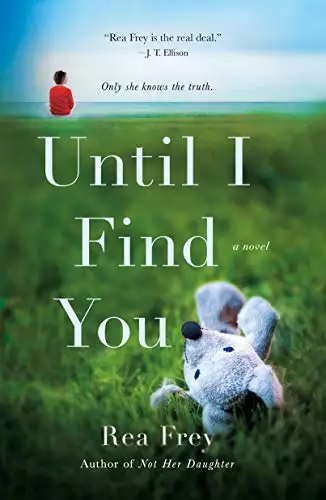

Until I Find You

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In Until I Find You, celebrated author Rea Frey brings you her most explosive, emotional, taut domestic drama yet about the powerful bond between mothers and children…and how far one woman will go to bring her son home.

2 floors. 55 steps to go up. 40 more to the crib.

Since Rebecca Gray was diagnosed with a degenerative eye disease, everything in her life consists of numbers. Each day her world grows a little darker and each step becomes a little more dangerous.

Following days of feeling like someone’s watching her, Bec awakes at home to the cries of her son in his nursery. When it’s clear he’s not going to settle, Bec goes to check on him.

She reaches in. Picks him up.

But he’s not her son.

And no one believes her.

One woman’s desperate search for her son . . .

In a world where seeing is believing, Bec must rely on her own conviction and a mother’s instinct to uncover the truth about what happened to her baby and bring him home for good.

A Macmillan Audio production from St. Martin's Griffin

“A beautifully, poignant, emotional story, Until I Find You examines what it means to trust yourself, even in a world where seeing is believing, and you can’t see to believe. With well-written characters and suffused with emotion, Until I Find You is a riveting story about the power of a mother’s love.” -Christina McDonald, USA Today Bestselling Author

Release date: August 11, 2020

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Until I Find You

Rea Frey

BEC

Someone’s coming.

I push the stroller. My feet expertly navigate the familiar path toward the park without my cane. Footsteps advance behind me. The swish of fabric between hurried thighs. The clop of a shoe on pavement. Measured, but gaining with every step. Blood whooshes through my ears, a distraction.

One more block until the park’s entrance. My world blots behind my sunglasses, smeared and dreamy. A few errant hairs whip across my face. My toe catches a crack, and my ankle painfully twists.

No time to stop.

My thighs burn. A few more steps. Finally, I make a sharp left into the park’s entrance. Jackson’s anklet jingles from the blistering pace.

“Hang on, sweet boy. Almost there. Almost.” The relentless August sun sizzles in the sky, and I adjust my ball cap with a trembling hand. Uncertain, I stop and wait for either the rush of footsteps to pass, or to approach and attack. Instead, nothing.

I lick my dry lips and half turn, one hand still securely fastened on my son’s stroller. “Hello?” The wind stalls. The hairs bristle on the back of my neck. My world goes unnaturally still, until I choke on my own warped breath.

I waver on the sidewalk and then lunge toward the entrance to Wilder. The stroller is my guide as I half walk, half jog, knowing precisely how many steps I must take to reach the other side of the gate.

Twenty.

My heart thumps, a manic metronome. Jackson squeals and kicks his foot. The bells again.

Ten.

The footsteps echo in my ears. The stroller rams an obstacle in the way and flattens it. I swerve and cry out in surprise.

Five.

I reach the gate, hurtle through to a din of voices. Somewhere in the distance, a lawn mower stutters then chugs to life.

Safe.

I slide toward the ground and drop my head between my knees. My ears prick for the stranger behind me, but all is lost. A plane roars overhead, probably heading for Chicago. Birds aggressively chirp as the sun continues to crisp my already pink shoulders. A car horn honks on the parallel street. Someone blows a whistle. My body shudders from the surge of adrenaline. I sit until I regain my composure and then push to shaky legs.

I check Jackson, dragging my hands over the length of his body—his strong little fingers, his plump thighs, and perpetually kicking feet—and blot my face with his spit-up blanket. Just when I think I’m safe, a hand encircles my wrist.

“Miss?”

I jerk back and suck a surprised breath.

The hand drops. “I’m sorry,” a woman’s voice says. “I didn’t mean to scare you. You dropped this.” Something jingles and lands in my upturned palm: Jackson’s anklet.

I smooth my fingers over the bells. “Thanks.” I bend over the stroller, grip his ankle, and reattach them. I tickle the bottom of his foot, and he murmurs.

“Are the bells so you can hear him?” the woman asks. “Are you…?”

“Blind? Yes.” I straighten. “I am.”

“That’s cool. I’ve never seen that before.”

I assume she means the bells. I almost make a joke—neither have I!—but instead, I smile. “It’s a little early for him to wear them,” I explain. “They’re more for when he becomes mobile, but I want him to get used to them.”

“That’s smart.”

I’m not sure if she’s waiting for me to say something else. “Thanks again,” I offer.

“No problem. Have a good day.”

She leaves. My hands clamp around the stroller’s handle. Was she the one behind me? I stall at the gate and wonder if I should just go back home. I remind myself where I am—in one of the safest suburbs outside of Chicago—not in some sketchy place. I’m not being followed.

It’s fine.

To prove it, I remove my cane, unfold it, and brace it on the path. I maneuver Jackson’s stroller behind and sweep my cane in front, searching for more obstacles or unsuspecting feet.

I weave toward Cottage Hill and pass the wedding garden, the Wilder Mansion, and the art museum. Finally, I wind around the arboretum. I leave the conservatory for last, pulling Jackson through colorful flower breeds, active butterflies, and rows of green. My heart still betrays my calm exterior, but whoever was there is gone.

I whisk my T-shirt from my body. Jackson babbles and then lets out a sharp cry. I adjust the brim of his stroller so his eyes aren’t directly hit by the sun. I lower my baseball cap and head toward the playground. The rubber flooring shifts beneath my cane.

Wilder Park is packed with last-minute late-summer activity. I do a lap around the playground and then angle my cane toward a bench to check for occupants. Once I confirm it’s empty, I settle and park the stroller beside me. I keep my ears alert for Jess or Beth. I think about calling Crystal to join us, but then remember she has an interior design job today.

I place my hand on Jackson’s leg, the small jingle of his anklet a comfort. Suddenly, I am overcome with hunger. I rummage in the diaper bag for a banana, peel it, and reach again for Jackson, who is playing with his pacifier. He furiously sucks then knocks it out of his mouth. He giggles every time I hand it back to him.

I replay what just happened. If someone had attacked me, I wouldn’t have been able to defend myself or identify the perpetrator. A shiver courses the length of my spine. Though Jackson is technically easy—healthy, no colic, a decent sleeper—this stage of life is not. Chris died a year ago, and though it’s been twelve months since the accident, sometimes it feels like it’s been twelve days.

Jackson’s life flashes before me. Not the happy baby playing in his stroller, but the other parts. The first time he gets really sick. The first time he has to go to the emergency room, and I’m all alone. The first time I don’t know what to do when something is wrong. The first time he runs away from me in public and isn’t wearing bells to alert me to his location.

Will I be able to keep him safe, to protect him?

I will the dark cloud away, but uneasiness pierces my skin like a warning. I fan my shirt, swallow, close my eyes behind my sunglasses, and adjust my ball cap.

The world shrinks. I try to swallow, but my throat constricts. I claw air.

I can’t breathe. I’m drowning. My heart is going to explode. I’m going to die.

I lurch off the bench and walk a few paces, churning my arms toward my chest to produce air. I gasp, tell myself to breathe, tell myself to do something.

When I think I’m going to faint, I exhale completely, then sip in a shallow breath. I veer toward a tree, fingers grasping, and reach its chalky bark. In, out. In, out. Breathe, Rebecca. Breathe.

Concerned whispers crescendo around me while I remember how to breathe. I mentally force my limbs to relax, soften my jaw, and count to ten. After a few toxic moments, I retrace my steps back to the bench.

I just left my baby alone.

Jackson’s right foot twitches and jingles from the stroller; he’s blissfully unaware that his mother just had a panic attack. I calm myself, but my heart continues to knock around my chest like a pinball. I open a bottle of water and lift it to my lips with trembling hands. I exhale and massage my chest. The footsteps. The panic attack. These recurring fears …

“Hey, lady. Fancy meeting you here.” Jess leans down and delivers a kiss to my cheek. Her scent—sweet, like honey crisp apples—does little to dissuade my terrified mood.

“Hi. Sit, sit.” I rearrange my voice to neutral and move the diaper bag to make room.

Jess positions her stroller beside mine. Beth sits next to her, her three-month-old baby, Trevor, always in a ring sling or strapped to her chest.

“How’s the morning?” Beth asks.

I tell them both about the footsteps and the woman who returned the bells, but conveniently leave out the part about the panic attack.

Beth leans closer. “Scary. Who do you think was following you?”

“I’m not sure,” I say.

“You should have called,” Jess says. “I’m always happy to walk with you.”

“That’s not exactly on your way.”

“Oh, please. I could use the extra exercise.”

I roll my eyes at her disparaging comment, because Beth and I both know she loves her curves.

“Anyway, it’s sleep deprivation,” Jess continues. “Makes you hallucinate. I remember when Baxter was Jackson’s age and waking up every two hours, I literally thought I was going to lose my mind. I would put things in odd places. I was even convinced Rob was cheating.”

I laugh. “Rob would never cheat on you.”

“Exactly my point.” She turns to me. “Have you thought about hiring a nanny?”

“Yeah,” Beth adds. “Especially with everything you’ve been through.”

My stomach clenches at those words: everything you’ve been through. After Chris died, I moved in with my mother so she could essentially become Jackson’s nanny. And then, just two months ago, she died too. Though her death wasn’t a surprise due to her lifelong heart condition, no one is ever prepared to lose a parent. “I can’t afford it.”

“Like I’ve said before, Rob and I are happy to pitch in—”

I lift my hand to stop her. “And I appreciate it. I really do. But I’m not ready to have someone in my space when I’m just getting used to it being empty. I need to get comfortable taking care of Jackson on my own.”

“That makes sense,” Beth assures me.

“It does.” Jess pats my thigh. “But you’re not a martyr, okay? Everyone needs help.”

“I know.” I adjust my sunglasses and rearrange my face in hopes of hiding the real emotions I feel. “What’s new with both of you?”

“Can I vent for a second?” Beth asks. She situates closer to us on the bench. Thanks to the visual Jess supplied, I know Beth is blond, petite, and impossibly fit—and is perpetually in a state of crisis. She’s practicing attachment parenting, which, in her mind, keeps her glued to her son twenty-four hours a day. I’ve never even held him.

“Vent away,” I say.

“Okay.” She drops her voice. “Like, I love this little guy, truly. But sometimes, when it’s just the two of us in the house all day, I fantasize about just running away somewhere. Or going out to take a walk. I’d never do it, of course,” she rushes to add. “But I just have this feeling like … I’m never going to be alone again.”

“Nanny,” Jess trills. “I’m telling you. Quit this attachment parenting crap and get yourself a nanny. And if she’s hot, she can even occupy your husband so you don’t have to.”

I slap Jess’s arm. “Don’t say that. You’d be totally devastated if Rob ever did cheat.”

“Would I though? One less thing I’d have to do at night,” she mumbles.

“That’s not attachment parenting,” I assure Beth. “That’s how every new mom feels sometimes.”

Beth bounces Trevor, her voice vibrating. “But am I a terrible human? Are you both sitting there judging me?”

“We don’t have time to judge you,” Jess jokes.

“You never complain, Rebecca,” Beth says.

“Who, me?” I ask. “I complain.”

I imagine Beth and Jess giving each other a look. “You don’t,” Jess says. “Ever. Which makes zero sense, considering…”

Considering your husband and mother died and you’re raising a baby all by yourself.

I shrug. “I learned a long time ago that complaining doesn’t change anything, so why bother?”

“Complaining is my hobby,” Beth says. “And I realize I don’t have anything to complain about. I mean, not really.”

I roll my eyes. “Beth, you’re allowed to feel however you want. Don’t compare your life to mine. For your own good.”

“But your baby is perfect,” Beth whines. “If you ever want to trade, just let me know.”

I laugh. “I’ll let you know.” I tune in and out as they gripe about their babies and husbands. I add in my two cents, wanting to tell them my deepest thoughts on the subject, but decide against it. Their voices come and go. My eyes flutter—closed, open, closed, open—and before I know it, I’ve accidentally fallen asleep.

2

BEC

After the park—and my unexpected nap—I listen for other people crossing the intersection and begin the grid-like walk back toward the house. I think of the chores I need to finish and the dinner I will prepare: steak, salad, and roasted rosemary potatoes. The steps I will go through. How I will set the table. How I will rely on timers and taste.

I approach the front of the house and fold my cane. Sweat has cropped up along my forehead. I wick away the moisture and fish my key from my back pocket. I bring it to the lock, but it smacks air. I reach forward and find the lock with my fingers.

The door is open.

I recoil, stunned. For the third time today, my pulse begins to race. I fumble for my phone, drop it, then retrieve it from the grass. Who can I possibly call? I spin around in an agitated circle, edge a few steps back, and stop. Am I being robbed? Are my earlier fears of being followed coming true?

Don’t go in. I heed my own warning and pull Jackson’s stroller to the edge of the driveway. Someone is always in the house, or crouched in a closet, or, God forbid, in the shower. I think about the alarm. Did I forget to set it?

Think, Rebecca. Think. I stall on the driveway and call Jess.

“Miss me already?”

“My front door is open.”

“What?”

“I just got home and my front door is open.” Saying it out loud makes me take another few steps toward the street.

“Don’t move. I’ll call the police.”

“You don’t have to call the police.”

“Rebecca, I’m calling the police. Do not go into the house. Do you hear me? I’ll be right there.”

I exhale and push and pull Jackson’s stroller in a lulling motion until Jess arrives.

“God, I hate running,” she pants. Her tennis shoes thud to a halt. She hitches forward and rests her hands on her knees. “It’s for the birds.” She grunts then straightens. “Police still aren’t here?”

I shake my head. A curl of hair brushes my cheek as she loops a sturdy arm around my shoulder.

“Keeping things interesting in old Elmhurst, huh?”

“Where’s Baxter?”

“Nanny. Told you they’re helpful.” She drops her arm as she continues to catch her breath. “Do you really think someone broke in?”

“I hope not.” I think of my cello, my computer, any valuables I have scattered about.

“Maybe you just didn’t shut the door all the way?”

“Maybe.” I always shut the door.

After a few anxious minutes, police sirens bleep and stutter along our street. My fingers tighten on the stroller as I imagine neighbors straining on their front porches, whispering behind cupped hands about the paranoid blind lady. This is not a neighborhood where cops do regular drive-bys. The red and blue lights pierce the blurred veil of my vision, and I squint behind my sunglasses.

A car door opens and shuts and then a lone officer approaches. “Ma’am?”

“Hi, I’m the one who called,” Jess says. “This is Rebecca Gray. She lives here. She’s…”

“I’m blind,” I explain. “When I got back from my walk, my front door was open. And I’m positive I shut it before I left.”

“Officer Toby.” He thrusts a hand in my direction. “Do you have an alarm?”

“I do.” I consider the possibility that I could have forgotten to arm it, but it doesn’t add up. “I always set it before I leave.”

“And the alarm hasn’t gone off?”

I shake my head. “No.”

“Have you gone into the home, ma’am?” His radio squawks with a string of garbled commands.

“No.”

“Good. I’m going to check the perimeter of the property and the interior. Please stay out here until I’ve completed the search.”

“Thanks, Officer.” Jess whistles when he walks away. “Who knew Elmhurst had such hot cops?”

I laugh and elbow her. Another cop name floats through my mind. To distract myself until Toby returns, I blurt: “I used to date a cop.”

“What? When?”

I shrug and shush Jackson as he fusses in his stroller. I reach around for his pacifier and pop it back into his mouth. “A lifetime ago. Before Chris.” Just saying my husband’s name sends a pang of fresh grief through my gut. “I met him when I still had my sight. I was twenty-five. He was a cop trying to make detective with CPD. Both of our careers were flourishing.”

“So what happened?”

“He got transferred to Florida,” I say. Though we both assumed we’d get married, have kids, and live in the city, when he got an offer to lead a narcotics unit, he took it.

“Ugh. Florida? No wonder you broke up.”

I playfully slap her arm.

“That wasn’t it, but I couldn’t leave the symphony. And he couldn’t miss out on such a great opportunity.” I shrug. “We were both realistic about long distance. Once he left, my sight got worse. I met Chris when he was volunteering at the Chicago Lighthouse.”

“What in the hell is that?”

“It’s a community center for the visually impaired.”

“Then Chris was a rebound.”

I roll my eyes. “Chris was not a rebound.”

“Chris was totally a rebound.”

“No, he was just there when I needed him.” I smile. “Chris was always there for me. He was dependable.”

“Like a minivan.”

“He was a bit like a minivan.” My heart lifts just joking about Chris. This is what I want to do more of, I remind myself. Talk about him as if he’s right here. Before I can say anything else, Jess leans in.

“Hottie approaching.”

“Ma’am, the perimeter and interior are secure. No sign of forced entry. Nothing suspicious in or around the property. I’m happy to do a walk-through with you to make sure nothing is out of place.”

“That’s not necessary.” I remove my ball cap and run a hand through my sweaty hair. “I’m sorry about this.”

“No problem. You ladies have a great day, okay?”

“Thanks so much, Officer.” Jess lightly touches my elbow. “Want me to come in with you?”

“No, I’m fine. Thanks for coming over.” I hug her, wave good-bye, and head inside. I shut and lock the front door. “Is Mama paranoid or what?” I remove Jackson from his stroller. His body is sticky as I settle him on one hip. I peel off my T-shirt and invite cool air to flow in from the gap. “It sure is hot out there, huh? I’m ready for fall. Are you?” We walk to the kitchen, and I open the freezer and stick my head in and play peek-a-boo a few times. His hearty chuckle squeezes my heart until I think it might explode.

“Okay, let’s get you settled so Mama can make dinner.” I walk the few steps to deposit him in his Pack ’n Play by the kitchen table, except it’s not where I left it. I rotate, inch by inch. Chills stud the back of my neck. I stall in the kitchen, moving methodically to retrace my steps. I round the corner and shuffle toward the middle of the living room, until I bump into something: his playpen.

My nerves sizzle. I would never put the Pack ’n Play in the middle of the living room. Because of my sight, I place most furniture on the perimeter of every room, leaving a wide open space to pass through. I’m certain it was by the kitchen table this morning. Could the cop have moved it?

I retreat slowly from the room, as though the playpen might detonate. I call Jess’s number again, fit Jackson back in his carrier, and leave the house as fast as I can.

3

BEC

Sometime in the night, Jackson wakes me. I open my eyes and fiddle with the baby monitor, but his cries stalk the hallway. I don’t bother checking the time and instead throw the duvet back and sit up.

My thoughts ping around as they do each night, when I lie awake for hours and wait for Jackson to signal he’s hungry. Ironically, he’s only been waking a few times per night. Now, I travel the hallway toward his nursery. The absence of morning light is like wading through ink.

At his door, the cries grow more urgent.

“Hold on, little guy. Mama’s here.” I cross to the crib. I lower my arms in, but he’s not where he usually is. “Did you roll?” I scoop again, but my grip comes away bare. I rub my hands across the sheets and frantically scour every inch of the crib. “Jackson?” I traverse and skim again.

Nothing.

The cries intensify, but they aren’t coming from the crib. Now, they’re behind me. I whip around. “Jackson?” I rush out of his room and down the hall. The cry shifts again, as if bouncing freely through the house. I fumble for the baby monitor on my nightstand and knock over my water glass. It thuds against the carpet. Back in the hallway, I strain to hear exactly where he is.

Downstairs?

“Oh my God.” I ignore the logical part of my brain that knows a three-month-old can’t escape his crib, and I sprint downstairs anyway. My toe bumps into something. I crouch down and connect with a tiny nose, mouth, and chin. But it’s not flesh I feel—it’s plastic. A baby doll? I check to make sure. The doll cries harder, and I drop it and spin around in my foyer. “Jackson?” I call his name again, and mid-cry, he cuts off. The house grows deathly quiet, except for my chaotic breath.

A crack of lightning brings me out of it. I jolt awake, drenched, my heart a jackhammer. I lie in my bed, queasy with nerves. “It’s just a dream,” I reassure myself. “You’re okay.” I reach for the glass of water on my nightstand and suck down the last remaining drops. I collapse back in bed. Thunder rolls outside, then another flash of lightning.

The nightmares are becoming so real.

I snake a shaky hand over my face and wipe away the sweat. The events from yesterday drift into focus: the footsteps. The open door. The moved playpen. Last night, Jess worked hard to reassure me that my exhaustion is to blame, but I’m not so sure.

I gauge the empty space beside me and run a hand over the sheets. A sob catches in my throat. I squeeze my eyes shut until the outline of Chris’s face fires in my memory—the slightly crooked nose, broken twice from college rugby, the large amber eyes and impossibly thick lashes, the tiny cleft in his chin. I reach out as though I can still press a finger into the dimpled flesh. My hand fists around air, drops, resettles.

I roll back over. Nights and mornings are always the worst. I can keep myself busy during the day, but at night, when I settle into bed, his absence is the loudest thing in the room. That, coupled with all of these terrors about Jackson—Jackson crying, but I can’t find him; Jackson tumbling from my arms down the stairs; Jackson floating away in a river—it’s enough to make me want to boycott my bedroom entirely.

I press the button on my alarm clock to tell me the time. It’s only 4 A.M. I sit up, slip on my robe, and listen for Jackson at the top of the stairs. His white noise machine whooshes on low from his nursery down the hall.

It’s still odd that I live in my mother’s house, a dusty old relic on one of the best streets in Elmhurst, Illinois. Its drab interior, leaky windows, and outdated roof made me think about selling, but I was too tired to pack, sort, and figure out where to move again after her funeral. Plus, it had once been my home too. I was ready to make it that way again.

Now, I carefully navigate down the stairs, my fingers cruising over the worn banister. At the bottom, I pass the sitting room I never actually sit in—badly in need of paint and fresh curtains—the monstrous dining room, the open foyer, and the cozy living room with the sailboat wallpaper. I used to stare at that wallpaper for hours as a child, until my eyes grew blurry and the boats blended together into a deep ocean blue.

Later, as an adult, when I found out I was going to lose my vision, I’d walk to Lake Michigan, sit on the beach, and stare at the water. I’d let the calm wash over me and commit the exact hue to memory—the same blue as my childhood wallpaper—and focus on how the water glittered and churned. I’d close my eyes and get used to hearing, not seeing. When my vision worsened, Chris continued to bring me to the water every Sunday. He didn’t talk. He didn’t ask questions. He just let me be.

Since his death, I haven’t been back even once.

I turn the corner into the kitchen, fill the kettle, and flick on the burner. Updating my childhood home will be the very first renovation project I tackle with Crystal, an interior designer I met at a grief group. Six months after Chris died, I’d waddled into the group with my pregnant belly, instantly wanting to leave, and that was when Crystal helped me find a seat. She didn’t ask about my vision or why I was there, and I didn’t ask her either.

We talked about other things: our careers and living in Elmhurst, though we had both lost our husbands. It was over a month before I even knew she had a daughter. I quickly learned she didn’t like talking about her life—as if the mere mention of the people who composed it would somehow alert the universe to take them all away too. Not many people understood that, but I did. There, in that room full of Kleenex and anguish, was the most connected I’d felt to anyone in a really long time. We’d been on a steady incline to genuine friendship ever since.

Upstairs, the baby cries. My body tingles as he calls. I shake the electricity from my limbs and wait to see if he will settle back to sleep, but he continues to cry.

I walk the hall again and trek upstairs: fifty-five steps. From landing to nursery: thirty-five. It is amazing how important math has become in daily life. How angles and steps can mean the difference between a smooth transition from room to room or a smashed nose or stubbed toe. While all visually impaired people have their blindisms—some people rock back and forth, some people listen with their mouths open, intent on absorbing every word—mine is counting steps. I don’t need to count steps. I am oriented to our home and neighborhood and am blessed with a photographic memory, but it is my tic.

I crack the door and ease inside. My mother helped me decorate. She picked the Pinterest-worthy wallpaper. The elephant decals. The Crate and Kids dresser and changing table. I walk toward the large crib and stare into it.

The room is black. The shape of my son seizes my heart. His little body plumps beneath his onesie—a foggy halo—but a gaping hole appears where his head should be. I picture his exquisite gray eyes, like twin marbles bobbing beneath water. Where are they? My breathing intensifies. I place my hand gently on his belly. He jerks awake in the inky darkness.

There. There’s my baby.

I slap a hand to my heart. The air escapes in an audible whoosh. The ugly black hole recedes as his face hardens in my mind. My hands traverse his body—the creased palms, the wiggly legs, the warm belly. It takes a moment for him to register in my brain first, then spring to life in front of me. He is here. He is real. I step back.

My eyes are playing tricks again.

It’s an unwelcome side effect of Stargardt disease—besides losing my central vision, I also see shapes shift in the dark with what little sight I retain.

I scoop his pliable body out of the crib and find the rocking chair. He hunts for my breast. His tiny fist works against my chest as he drinks. I cast a map of his face in my mind and caress every feature. The fuzzy forehead. His thick lashes and squishy nose. His tiny scoop of a chin. Love fills my hand, my body, this chair, my world. I remember when he was placed into my arms at the hospital, I’d memorized every part of him. The wrinkled hands and impossibly compact feet. The down-turned lips. His crazy fingernails, which were so long, I had to cover his hands with socks to keep him from scratching himself. A surge of grief flattens me. Chris was supposed to be here. Chris was supposed to become a father. He and I spent so much time discussing our future, making plans for time we’d never have instead of just enjoying the moment.

What a waste.

I let the feelings come—now knowing that resisting grief only makes it worse—and wait until they pass. “Who’s a good boy?” I stroke Jackson’s cheek and mess with the bumpy skin close to his right ear. The pediatrician explained how to feel for rashes, how to differentiate between eczema, psoriasis, diaper rash, or even chicken pox. This is eczema.

I take inventory of the rest of his skin—all clear—and wind my fingers through his wispy hair. He drains my left breast, then my right. I resist the urge to fall asleep. So many times during the day, I try to nap and almost get there, but something happens: the phone rings. The baby cries. He’s wide awake and wants to be entertained. But the sleeplessness is worth it for moments like these.

I rock Jackson until he is milk drunk and lay him back in his crib. I leave his door cracked and pad back downstairs to the kitchen, not even realizing the kettle has been whistling. The angry steam hisses from the spout. I flick off the burner and pour myself a cup.

I sip my tea. The silence consumes me. I ask Google Home to play my Spotify symphony playlist and briefly conjure my younger, sighted self in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, followed by vision symptoms I could no longer ignore, which inevitably led to a diagnosis of Stargardt disease and Charles Bonnet syndrome. As my vision went, it was like staring at a painting whose center had been wiped clean. It was manageable at first, like having really bad vision and forgetting

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...