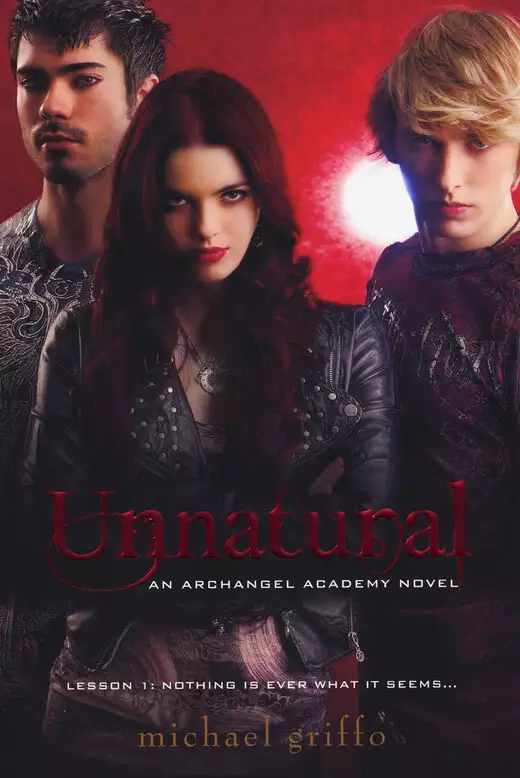

Unnatural

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In the town of Eden in northwestern England stands the exclusive boarding school known as Archangel Academy. Ancient and imposing, it's a place filled with secrets. Just like its students. . . For Michael Howard, being plucked from his Nebraska hometown and sent thousands of miles away is as close as he's ever come to a miracle. In Weeping Water, he felt trapped, alone. At Archangel Academy, Michael belongs. And in Ciaran, Penry, and especially Ciaran's enigmatic half-brother Ronan, Michael finds friendship deeper than he's ever known. But Michael's only beginning to understand what makes the Academy so special. Ronan is a vampire--part of a hybrid clan who are outcasts even among other vampires. Within the Academy's confines exists a ruthless world of deadly rivalries and shifting alliances, of clandestine love and forbidden temptations. And soon Michael will confront the destiny that brought him here--and a danger more powerful than he can imagine. . . Michael Griffo is an award-winning writer and one of six playwrights whose career will be tracked by WritersInsight.com until 2010. He is a graduate of New York University, has studied at Playwrights Horizons and Gotham Writers Workshop, and has written several screenplays.

Release date: March 1, 2011

Publisher: Kensington Teen

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Unnatural

Michael Griffo

The rain had finally stopped, but it had poured hard and long during the night, the sudden storm catching the land unprepared for such a prolonged onslaught. From Michael’s bedroom window he could see the dirt road that led up to his house had flooded and the passageway that could lead him to another place, any place away from here, was broken, unusable. Today would not be the day he would be set free.

Ever since Michael was old enough to understand there was a world outside of his home, his school, his entire town, he had fantasized about leaving it all behind. Setting foot on the dirt path that began a few inches below his front steps and walking, walking, walking until the dirt road brought him somewhere else, somewhere that for him was better. He didn’t know where that place was, he didn’t know what it looked like; he only knew, he felt, that it existed.

Or was it all just foolish hope? Peering down from his second-floor window at the rain-drenched earth below, at the muddy river separating his home from everything else, he wondered if he was wrong. Was his dream of escape just that, a dream and nothing more? Would this be his view for all time? A harsh, unaccepting land that, despite living here for thirteen of his sixteen years, made him feel like an intruder. Leave! He could hear the wind command, This place is not for you. But go where?

On the front lawn he saw a meadowlark, smaller than typical but still robust-looking, drink from the weather-beaten birdbath that overflowed with fresh rainwater. Drinking, drinking, drinking as if its thirst could not be quenched. It stopped and surveyed the area, singing its familiar melodious tune, da-da-DAH-da, da-da-da, and pausing only when it caught Michael’s stare. Switch places with me, Michael thought. Let me rest on the brink of another flight, and you sit here and wait.

And where would you go? the meadowlark asked. You know nothing of the world beyond this dirt.

Nothing now, but I’m willing to learn. The lark blinked, its yellow feathers bristling slightly, but I’m not willing to forget everything that I know. Da-da-DAH-da, da-da-da.

How wonderful would it be to forget everything? Forget that the mornings did not bring with them the promise of excitement, but just another day. Forget that the evenings did not bring with them the anticipation of adventure, but just darkness. Forget it all and start fresh, start over.

The meadowlark was walking along the ledge of the birdbath, interrupting the stagnant water this time with its feet instead of its beak, looking just as impatient as it did wise. You can never start over. The new life you may create is filled with memories of the old one. The new person you may become retains the essence of who you were.

No, Michael thought, I want to escape all this. I want to escape who I am!

Humans, such a foolish species, the lark thought. Da-da-DAH-da da-da-da. You can never escape your true self and you’ll never be able to escape this world until you accept that.

Michael watched the meadowlark fly away, perhaps with a destination in mind, perhaps just willing to follow the current—regardless, out of view, gone. And Michael remained. The water in the birdbath still rippled with the lark’s memory, retaining what was once there, proof that there had been a visitor. Michael wondered if he would leave behind any proof that he was here when he left, if he ever left. Not that he cared if anyone remembered his presence, but simply to leave behind proof that he had existed before he began to live.

He turned his back to the window, the meadowlark’s memory and song, the flooded earth—none of that truly belonged to him anyway—and he gazed upon his room. For now, this sanctuary was all he had. He was grateful for it, grateful to have some place to wait until the waters receded and his path could lead him away from here.

But that would not happen today. Today his world, as wrong as it was, would have to do.

Like a snake slithering out of the brush, a bead of sweat emerged from his wavy, unkempt brown hair. Alone, but determined, it slowly slid down the right side of his forehead, less than an inch from his hazel-colored eye, then gaining momentum, it glided over his sharp, tanned cheekbone. Now the bead grew into a streak, a line of perspiration, half the length of his face. He turned his head faintly to the left and the streak picked up more speed and raced toward his mouth, zigzagging slightly but effortlessly as it traveled over the stubble on his cheek and stopping only when it landed at the corner of his mouth. He didn’t move. The streak grew into a bubble, a mixture of water and salt, and hung there nestled between his lips until his tongue, in one quick, fluid movement, flicked it away. Then it was gone. All that remained as proof that it had once existed was the wet stain of perspiration that ran from his forehead to his mouth. That and Michael’s memory.

Sitting next to his grandpa in the front seat of his beat-up ’98 Ford Ranger, Michael had been watching R.J. in the rearview mirror as he pumped gas. He was still watching him, actually; he couldn’t help it. His viewing choices were his grandpa’s unwelcoming face, the flat dirt road, the dilapidated Highway 50 gas station, the cloudless blue sky, or R.J. Without hesitation, his eyes had found the gas station attendant, as they always did when he accompanied his grandpa on Saturday mornings to fill up the tank on their way to the recycling center. Today, the last Saturday morning in August and a particularly hot one, found R.J. more languid than usual.

He pressed his lean body against the Ranger, his left arm raised overhead and resting on the side of the truck so that if Michael inched forward a bit in his seat, he could see the hairs of R.J.’s armpits jutting out from underneath his loose, well-worn T-shirt. Michael inhaled deeply, the smell of gasoline filling him, and his eyes followed that smell to the pump that R.J. held in his right hand. Michael’s eyes moved from the pump to R.J.’s long index finger wrapped around the pump’s trigger and then traveled along the vein that lay just underneath R.J.’s skin. The vein, large and pronounced, started at his knuckle, spread to his wrist, and then moved along the length of his arm until it ended at the crease of his elbow. His arm, flexed as he pumped the gas, looked strong, and Michael wondered what it would feel like. Would it feel like his own arm or like something completely different? Something much better.

Absentmindedly, Michael touched his forearm; it was smooth and hot. He traced his own much smaller vein with his finger and he could feel his pulse, rapid, restless, new, and he wondered if beneath R.J.’s lazy demeanor his pulse was just as quick. Or was Michael the only one who felt speed underneath his skin?

The click of the gas pump ended all speculation. Michael shot a quick glance to his grandpa, who was staring out at the land, busy smoking his third Camel in an hour, since his grandmother refused to allow him to smoke inside the house. As always his mind, like Michael’s, was elsewhere.

Michael heard the snap as R.J. returned the nozzle to its cradle, the quick tick-tick-tick as he closed the gas cap, and the slam as he shut the cover of the gas lid. And just as he turned to look out his window, hoping to catch a whiff of R.J.’s scent as he walked around the car to collect the cash from his grandpa like he always did, R.J. decided to change the rules. He squatted down next to Michael’s window and peered into the truck.

“That’ll be twenty-seven fifty,” R.J. said in his usual low hum.

This was a surprise. Underneath his skin he felt his pulse increase, but Michael had learned not to show the outside world what was happening inside him and so his expression remained calm. Just another bored teenager sitting in a truck with his grandpa on a hot August Saturday morning. But he was much more than bored; R.J.’s face ignited curiosity.

Unable to turn away, Michael soaked it all in. Up close, Michael could see that there were a few more beads of sweat on R.J.’s forehead, lingering there, not yet ready to take the trip down his face. While Michael’s grandpa reached into his front pocket to pull out his cash, R.J. rested his chin on his forearm and closed his eyes. His eyelashes were like a girl’s, long, delicate, with a beautiful upcurl to them. Michael had the urge to run his finger through them as if they were strings of a harp. Like most of his urges, he repressed it.

How many freckles were on his slender nose? Six, eight … before Michael could finish counting, R.J. brushed his cheek against his arm, wiping away any telltale signs of perspiration that had remained, and looked up directly into Michael’s eyes. His mouth formed a smile and then words, “Hot today, ain’t it?”

Keep looking bored, Michael thought, uninterested, so no one will suspect. “Yeah,” Michael said, nodding his head.

“Gonna be a scorcher today,” Michael’s grandpa said, “but ya can’t trust those weathermen to know nothin’.”

R.J.’s face retained its expression, no change whatsoever. Was R.J. suppressing what he really felt too, or did he agree with Michael’s grandpa? “Can’t really trust anybody,” R.J. said. “Can ya, Mike?”

That sounded odd to Michael’s ears; nobody called him Mike. He wasn’t a Mike, it didn’t fit, but maybe it could be the name that only R.J. used. That would be okay. Michael cleared his throat and then replied, “Guess not.”

“Here.” Michael’s grandpa thrust some bills in front of Michael, and R.J. reached out to grab them. A beat later, Michael reached forward to grab the money and pass it along to R.J., but he was too late. Or maybe he was right on time? His fingers brushed against R.J.’s forearm and he discovered that R.J.’s skin was just as smooth as his, but much hotter and firmer than his own. Michael mumbled “sorry,” but he was drowned out by his grandpa’s command, “That’s twenty-eight there, Rudolph; credit me fifty cents next time.”

Rudolph. Michael’s grandpa was the only one who called him by his real name. Sounded more inappropriate than calling Michael Mike. But Mike and Rudolph? That had an exciting sound to it. Michael didn’t see R.J.’s patronizing smile; he kept his gaze down at the fingers that had recently touched his skin, but he did hear him. “Will do, sir.” He didn’t look back up until he heard the motor running and heard his grandpa shift the car into drive. He turned to catch one more glimpse of R.J.’s face, but he had stood up and all Michael could see was his hand stuffing the cash into the frayed pocket of his jeans. And then there was a breeze.

R.J.’s T-shirt lifted and for a moment his hip flank, sharply defined and smooth, was exposed. Michael thought it looked like a small hill on an otherwise flat plain where he could rest his head, maybe dream a little. As the truck pulled away, Michael looked through the rearview mirror, but the breeze had died and R.J.’s T-shirt covered that interesting piece of flesh. Later that night, Michael would remember it, though, because no matter how hard he tried, he just knew it was something he wouldn’t be able to forget.

After Michael helped his grandpa bring the cans and bottles to the recycling center, there were other errands to run. Had to pick up a new fog light at Sears that he would later be forced to watch his grandpa install in his mother’s car because she turned a corner too sharply and busted hers; then they had to drive over to the Home Depot to get a new toilet chain that Grandpa would watch Michael install in the downstairs bathroom; and of course it wouldn’t be Saturday if his grandpa didn’t play the Nebraska Lottery.

“Up to a hundred seventy million this week,” the redheaded cashier informed them.

“If I win, you and me’ll bust outta here,” Grandpa said.

“My bags are already packed!” the redheaded cashier chortled. Even though the cashier was roughly forty years younger than his grandpa and still what locals would call fine-lookin’, Michael had no doubt that if his grandpa came back next week waving a winning lottery ticket, she would hop in the Ranger to drive off with him to parts unknown. Weeping Water was not the kind of town that instilled loyalty in its residents, unless they had nowhere else to go.

But Michael did have some place he could go. He had started his life somewhere else, he was born someplace far, far from this town, where he could be living right now. But his mother had put an end to all of that. Why?! Why had she ruined everything? No. No sense blaming her now; the damage had already been done. He would just spend the rest of the day imagining how far from here he would travel if he were lucky enough to win the lottery.

When all the dinner dishes were washed and put away and his grandparents were sitting in their own separate chairs in front of the television, he finishing an after-dinner beer, she finishing yet another knitting project, Michael sat on his bed rereading A Separate Peace, one of his favorite novels, some music that he vaguely recognized filling the space of his room. Before he finished chapter one, his mother knocked on his door to ask the same question she’d been asking all summer long.

“Heya, honey, aren’t ya going out tonight?”

Grace Howard had once been a beautiful woman. So beautiful that she won a series of beauty pageants culminating in Miss Nebraska, which meant that she could fly to Atlantic City to participate in the Miss America contest. Pretty big stuff for any town desperate for some notoriety, incredibly huge stuff for a town like Weeping Water. She didn’t crack the top ten, but she did catch the eye of a young college student on vacation from England. Against the vehement protests of her parents, Grace nixed a return to Nebraska and instead flew to England with Vaughan. She had never done anything so spontaneous or rebellious in her entire life. Three months after the contest, she and Vaughan Howard got married on his family’s estate in Canterbury, roughly an hour southeast of London. Vaughan was her winning lottery ticket. Until she decided to rip it up into little pieces and return home, dragging her crying toddler with her.

“No, I need to finish this before school on Monday,” Michael lied with just a glance in his mother’s direction.

“But it’s the last weekend before school starts back up.”

Don’t remind me, Michael thought. “I know, that’s why I have to finish.”

His mother was in his room now, which meant that either she wanted to discuss something or she was incredibly bored and had exhausted all conversation with her parents. “Can’t believe you’re a sophomore already; my little guy’s gettin’ to be a man.” She was standing in front of the oak bookshelf, looking at the spines of all the books Michael had read and would most likely read again. They were his escape. It didn’t take a genius to figure that out. “I hated to read when I was your age; still can’t concentrate long enough to get through a magazine article.”

From behind, Michael’s mother still looked youthful. Her brown hair was full and fell an inch or two below her shoulders, her arms were taut and hadn’t yet gotten flabby, and her hips still held their curve. It’s when she turned to face Michael that he saw age had crept into her face prematurely. Michael knew that a thirty-seven-year-old woman shouldn’t look like that.

“You know Darlene’s daughter?”

“Who?”

“Darlene Garrison. Michael, sometimes …” Now she was fiddling with something on his desk. “Sometimes I don’t think you pay attention to anything except these books of yours. Darlene owns the beauty parlor A Cut Above; she does my hair. Her daughter, Jeralyn, is in your grade.”

Michael had no idea who Jeralyn Garrison was, so he lied again. “Oh yeah, I think so.”

“Where’d you get this?” His mother held up a Union Jack bumper sticker.

“I found it at the Sears auto store when I was there with Grandpa. He told me I couldn’t put the British flag on his Ranger. I told him I had no intention of doing that; I bought it ’cause I liked it.”

Michael saw the familiar glaze come over his mother’s eyes. He remained silent because he knew that if he kept on talking, if he asked her a direct question even, she wouldn’t hear him. She was in the room, but her mind wasn’t. Her heart might not be in the room either, but his mother rarely talked about what lay in her heart, so it was hard to tell about that. When she placed the bumper sticker gently back on his desk and turned to face him, he was compelled to speak despite knowing it might be futile.

“Do you ever miss London?”

Grace looked at her son. He doesn’t look a thing like me, does he? I don’t have blond hair, my skin isn’t so pale, my eyes aren’t green. If I hadn’t been there when the doctor pulled him out from inside of me, I would never believe this person was my flesh and blood. But he was, he is, she thought. In some ways, he’s all I’ll ever be able to truly call my own.

“No,” she lied. “I told you before, it’s a crowded, loud city. Dirty, no space to breathe, no clean air. I can’t believe you remember it; you were only three when we left.”

“I don’t really have memories, but impressions. I don’t know, I just get the feeling that I would like it.”

He doesn’t even sound like me, Grace thought. He never does. He says things that just don’t make sense, that make me question why I ever became a parent, why I ever wasted my life raising him. “You mean you just get the feeling that you’d like it better than here.”

And the change had begun. Michael saw his mother’s lips press against each other to form a smile that meant to convey anything but joy, her head tilt to the right, and her eyes fill with disbelief. Their roles had reversed. She was the emotionally reactive teenager and he was the insightful parent. Experience had taught him this conversation would not be any different from any other conversation he’d ever had with his mother about London or what their life was like before she brought him to this place, the place where she grew up, or what their life could be like if they moved back. Nothing important would be disclosed, nothing important would be shared between mother and son. And so he just went back to reading.

His mother paced the width of the room, once, twice. She hated when Michael asked about London. For her it was another lifetime ago, a mistake. No, not a mistake entirely. What should I call it? she thought. She couldn’t come up with a word. As always, the mention of London and her past made her fidgety, confused. The only thing she was certain of was that it was part of her past and that’s where it should remain. Yes, it should remain buried and silent. Because when she thought of London, all she thought of was him, Michael’s father. The man she ran away with and the man she eventually ran from. The man she once loved and would always love. The man she never wanted to see again. “Do me one favor,” Grace said before leaving her son alone. “When you get married, be a better husband than your father was.”

A cold sensation of fear trickled down Michael’s neck and found its resting place on his heart. It squeezed, it constricted, until Michael could hardly breathe and had to consciously put down his book and gasp, gasp for a breath that should have come easily. But his mother saw to it that it didn’t. She had to mention marriage and becoming a husband, didn’t she? If Michael didn’t know better, he’d think his mother was punishing him for bringing up London. And maybe she was. Lately she had been acting so erratically he had no idea what she was thinking. All he knew was that whenever his mother, or anyone for that matter, insinuated that he should get married and become a husband, he panicked. It just felt wrong. The only thing that made him feel worse was that, to everyone else, it felt perfectly right.

Just as his breathing returned to normal, he heard the medicine cabinet open, which could mean only one thing: His mother needed some comfort. Maybe it was the white pill; perhaps tonight it would be the blue pill. It didn’t matter. Michael didn’t have to see into the bathroom to know that his mother was taking a pill to calm her nerves. A pill before bedtime was the only thing that seemed to help her these days. That and a nice glass of white wine.

What happened to the mother who used to help me with my homework after dinner? Explain to me how to figure out percentages and the differences among the three branches of government. When did she stop wanting to help me and start wanting to create me in her image? Now Michael was pacing his room, back and forth, trying to figure out why his mother was no longer on his side, pacing, pacing, pacing, until he forced himself to stop moving. He gripped the windowsill and looked out into the night. The moonlight allowed him to see only a few yards of the dirt road; the rest was hidden in darkness, out of his reach once again. Why do I hate it here so much?! Maybe, just maybe, it had to do with what was taking place downstairs.

“Again with the wine,” Michael’s grandfather snickered.

“Should I drink whiskey?” Grace asked. “Would that make you happy? Oh, that’s right, there’s nothing that would make you happy.”

“Don’t you talk to me like that!”

“And don’t you dare tell me what to do!”

That was different. Michael’s mother didn’t usually talk back to her father. Guess the pills and the wine weren’t working as quickly to calm her as they usually did.

“Maybe if you weren’t drinking all the time, you’d be able to straighten out that son of yours.”

“You leave him out of this,” Grace said, much quieter. Ah, now the pills are kicking in. “He’s a good boy.”

“He ain’t no boy!” his grandfather shouted. “He’s like that fairy husband of yours!”

“He’s nothing like Vaughan!”

“Is too! A sissy boy and he ain’t gonnna ’mount to nothin’! Mark my words!”

“You shut your mouth, Daddy! Shut it! Michael is not … like that. He’s perfectly normal!”

But Michael knew his mother was wrong. He wasn’t normal. His grandfather didn’t have to come right out and say it; Michael knew what he was. He stared at his reflection in the window and he could see it in his own eyes. What he saw made him disgusted, scared, but yes, just a little excited even though he knew what he was seeing wasn’t right. Tomorrow at church he would pray that it would all go away, that he would be able to change who he was, but tonight … tonight he would lock his bedroom door, block out the sounds coming from downstairs, and think about R.J. And he would convince himself that it was the most natural thing in the world.

Not a word was spoken during the half-hour drive to church. It would be optimistic to think that Michael, his mother, and his grandparents were all engaged in private meditation, but the truth is, they had nothing to say to one another. At least nothing that would be appropriate to say en route to God’s house.

They took Grace’s gray Ford Taurus, complete with its new fog light, but Michael’s grandpa drove because Grace, who sat in the back with Michael, was too tired to drive. Hungover was more like it, but no one contradicted her. Why point out the obvious? So the only sounds that filled up the emptiness were the whir of the air conditioner, the crunch of the tires on the dirt road, and then the softer hum when they merged onto the highway. And of course the sounds that filled Michael’s head.

He turned to look at his mother, silent now, eyes closed, trying to sleep, summoning the strength to make it through another sermon perhaps, and heard the words she shouted to his grandpa last night: “He’s perfectly normal!” It wasn’t the first time he’d heard her say that or words just like it; they often argued about him when he wasn’t in the room and he imagined that their arguments were louder and their words more tactless when they knew he wasn’t in the house and there was no chance of his overhearing. Yes, the words bothered him, but worse was the sound of his mother’s voice, hopeful, a bit defiant, but mostly desperate because she knew even as she spoke the words that they weren’t the truth.

Michael wasn’t perfectly normal. And the older he got, the more of a problem it was becoming. But if only his mother supported him, maybe it wouldn’t have to be such a problem. Maybe he could handle everyone else’s criticisms and unkind comments if he knew she didn’t view him as such an incredible disappointment. Wasn’t his mother supposed to love him unconditionally? Wasn’t she supposed to defend him without letting her own doubts and fears emerge? Time and time again his mother failed him and she only succeeded in making him realize that he was on this earth by himself. He hated the feeling, but lately he was forced to admit that it was liberating. At least he knew where he stood.

“I’ll try to get that radio fixed this week,” Grandpa said. Now that they were in the openness of the church parking lot and not the confined space of the car, it was easier to speak.

Walking up the wooden steps of the church, he felt each plank bend and creak with his weight as if the steps were acting as guardians deciding if they should allow him entry or break in half and swallow him whole. He smiled to himself. How ironic; that’s how I already feel, swallowed up by the earth, silenced. He watched his mother and grandma smile and nod at the other parishioners. Occasionally his grandma would clasp another old woman’s hand, not out of affection really, but just a desire to connect to someone, anyone, but they too were silent. Only Grandpa made noise.

Whether welcoming men who looked as tired and weary as he did with a gruff hello or slapping someone on the back vigorously, his grandpa was heard. In the company of his kindred spirits he was simply unable to restrain his innate rowdy behavior even while clad in his iron-pressed Sunday clothes. Michael envied such freedom. To be able to act upon your instinct—now, that would truly be liberating. Unfortunately, his instinct was frowned upon by the church, so when he saw R.J. bound up the steps with some girl, some girl who wasn’t even pretty, he didn’t rush to him and slap him on his back or shake his soft, firm hand; he resolutely followed his family inside.

A few minutes later when all the pews were filled with bodies, either eager or resigned to spend the next hour in reflection, Michael looked around at his family, the congregation, at the people who inhabited his world, and he was overcome with a feeling of loneliness. He just didn’t belong. It struck him like a nail through the palm; he knew it in his mind, he felt it in his body, his soul … no, he didn’t want to contemplate his soul, not here, not surrounded by these strangers; he didn’t want to open his soul up to inspection and risk contamination by others.

Where was R.J.? He scoured the pews in front of him and couldn’t find his face. Bending down as if he needed to scratch his leg, he looked quickly behind him and there he was, next to her. Why was she giggling in church? And why did she look so ugly when she laughed? Michael looked at R.J. and he wasn’t laughing, but he was definitely smiling. And definitely not looking at him.

He gripped the back of the pew in front of him with both hands until his knuckles were white. In the distance he could hear Father Charles reciting something, a prayer, some words, and he tried to remember that, despite what those around him thought, even he was welcome in this house. He felt his eyes begin to water. No, he wouldn’t cry, not here, not now. Why was he acting like this? It was hardly his first time in church; isolation among this group was not a new sensation. Maybe he couldn’t pretend anymore. Maybe he couldn’t pretend that being different didn’t matter. Everyone has their breaking point. And that’s when he saw his mother reach hers.

The tears that Michael refused to shed poured quietly down his mother’s face, without fanfare, without a desire to be seen, just a part of her that could no longer remain locked away. Her face, however, was unburdened by sadness; on the contrary, it looked blank, which only confused Michael more. He had often seen his mother cry, after she had had too much to drink, when the paramedics carted her off once, twice, to a place where she could rest, a place where she didn’t want to go. But those times her tears were accompanied by shouts, screams, a face contorted with anger and fear; these tears were different, they were alone. His mother was crying, but it was as if she were discarding her tears because she had learned she had no use for them; tears no longer made a difference.

The Lord’s Prayer was being recited around them, and Michael wished he could stare straight ahead and mutter the words, but he couldn’t do anything but stare at his mother. What was happening to her? And for that matter to him? And why was she leaving?

Grace had grabbed her purse and was now awkwardly stepping in front of Michael and then the rest of the people in their pew until she reached the aisle. The voices continued speaking “as we forgive those who trespass against us,” but all heads turned to see Grace genuflect deeply and cross herself before turning and walking out of the church.

Michael looked at h

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...