- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

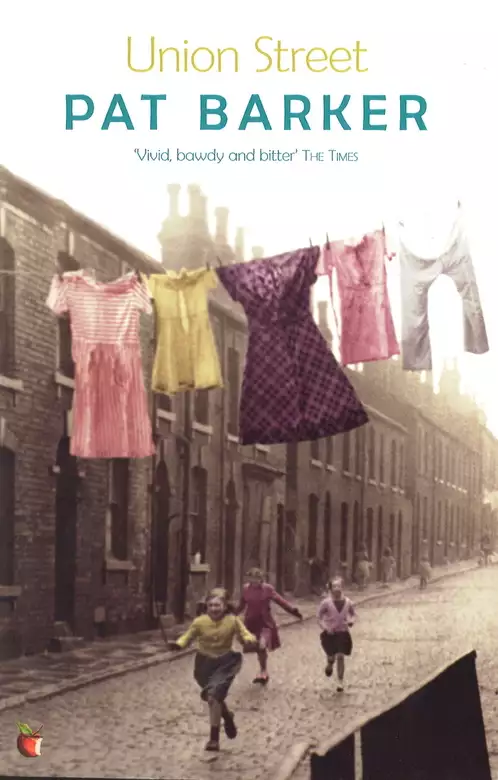

Synopsis

an early work by the winner of the 1995 Booker Prize

Release date: May 13, 1982

Publisher: Trafalgar Square

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Union Street

Pat Barker

There was a square of cardboard in the window where the glass had been smashed. During the night one corner had worked loose and scraped against the frame whenever the wind blew.

Kelly Brown, disturbed by the noise, turned over, throwing one arm across her sister’s face.

The older girl stirred in her sleep, grumbling a little through dry lips, and then, abruptly, woke.

‘I wish you’d watch what you’re doing. You nearly had my eye out there.’

Kelly opened her eyes, reluctantly. She lay in silence for a moment trying to identify the sound that had disturbed her. ‘It’s that thing,’ she said, finally. ‘It’s that bloody cardboard. It’s come unstuck.’

‘That wouldn’t be there either if you’d watch what you’re doing.’

‘Oh, I see. My fault. I suppose you weren’t there when it happened?’

Linda had pulled the bedclothes over her head. Kelly waited a moment, then jabbed her in the kidneys. Hard.

‘Time you were up.’ Outside, a man’s boots slurred over the cobbles: the first shift of the day. ‘You’ll be late.’

‘What’s it to you?’

‘You’ll get the sack.’

‘No, I won’t then, clever. Got the day off, haven’t I?’

‘I don’t know. Have you?’

No reply. Kelly was doubled up under the sheet, her body jack-knifed against the cold. As usual, Linda had pinched most of the blankets and all the eiderdown.

‘Well, have you?’

‘Cross me heart and hope to die, cut me throat if I tell a lie.’

‘Jammy bugger!’

‘I don’t mind turning out.’

‘Not much!’

‘You’ve nothing to turn out to.’

‘School.’

‘School!’

‘I didn’t notice you crying when you had to leave.’

Kelly abandoned the attempt to keep warm. She sat on the edge of the bed, sandpapering her arms with the palms of dirty hands. Then ran across the room to the chest of drawers.

As she pulled open the bottom drawer – the only one Linda would let her have – a characteristic smell met her.

‘You mucky bloody sod!’ The cold forgotten, she ran back to the bed and began dragging the blankets off her sister. ‘Why can’t you burn the buggers?’

‘With him sat there? How can I?’

Both girls glanced at the wall that divided their mother’s bedroom from their own. For a moment Kelly’s anger died down.

Then: ‘He wasn’t there last night.’

‘There was no fire.’

‘You could’ve lit one.’

‘What? At midnight? What do you think she’d say about that?’ Linda jerked her head towards the intervening wall.

‘Well, you could’ve wrapped them up and put them in the dustbin then. Only the lowest of the bloody low go on the way you do.’

‘What would you know about it?’

‘I know one thing, I’ll take bloody good care I never get like it.’

‘You will, dear. It’s nature.’

‘I don’t mean that.’

Though she did, perhaps. She looked at the hair in Linda’s armpits, at the breasts that shook and wobbled when she ran, and no, she didn’t want to get like that. And she certainly didn’t want to drip foul-smelling, brown blood out of her fanny every month. ‘Next one I find I’ll rub your bloody mucky face in.’

‘You and who else?’

‘It won’t need anybugger else.’

‘You! You’re not the size of twopenn’orth of copper.’

‘See if that stops me.’

There was a yell from the next bedroom. ‘For God’s sake, you two, shut up! There’s some of us still trying to sleep.’

‘No bloody wonder. On the hump all night.’

‘Linda!’

‘Notice she blames me. You’re getting to be a right cheeky little sod, you are.’

‘Did you hear me, Linda?’

‘Just watch it, that’s all.’

‘Linda!’

‘I’ll tell Kevin about you,’ Kelly said. ‘He wouldn’t be so keen getting his hand up if he knew what you were really like.’

‘Have I to come in there?’

The threat silenced both girls. With a final glare Kelly picked up her clothes and went downstairs to get dressed. On the landing she paused to look into her mother’s bedroom. There was a dark, bearded man zipping up his trousers. When he saw her his face twitched as if he wanted to smile. It wasn’t Wilf. It was a man she had never seen before.

She ran all the way downstairs, remembering, though only just in time, to jump over the hole in the passage where the floorboards had given way.

Dressed, she turned her attention to the fire. Since there were no sticks, she would have to try to light it on paper alone, a long and not always successful job. Muttering to herself, she reached up and pulled one of her mother’s sweaters from the airing line. There were sweaters of her own and Linda’s there but she liked her mother’s better. They were warmer, somehow, and she liked the smell.

She picked up the first sheet of newspaper. The face of a young soldier killed in Belfast disappeared beneath her scrumpling fingers. Then her mother came in, barefoot, wearing only a skirt and bra. The bunions on the sides of her feet were red with cold.

She was still angry. Or on the defensive. Kelly could tell at once by the way she moved.

‘I see you’ve nicked another of me sweaters. Beats me why you can’t wear your own. You’d think you had nowt to put on.’

She searched along the line and pulled down her old working jumper that had gone white under the armpits from deodorants and sweat. After a moment’s thought she rejected it in favour of a blue blouse, the sort of thing she would never normally have worn at work. It was because of him, the man upstairs.

Kelly sniffed hungrily at the sweater she was wearing, which held all the mingled smells of her mother’s body. Though the face she raised to her mother afterwards could not have been more hostile.

‘You got started on the fire, then? Good lass.’

‘I’d ’ve had it lit if there’d been owt to light it with.’

‘Yes, well, I forgot the sticks.’

She perched on the edge of the armchair and began pulling on her tights. Kelly watched. She went on twisting rolls of newspaper, the twists becoming more vicious as the silence continued.

At last she said, ‘Well, come on, then. Don’t keep us in suspense. Who is it?’

‘Who?’

Kelly drew a deep breath. ‘Him. Upstairs. The woolly-faced bugger with the squint.’

‘His name’s Arthur. And he doesn’t squint.’

‘He was just now when he looked at me.’

‘Oh, you’d make any bugger squint, you would!’

‘Does that mean Wilf’s had his chips?’

‘You could put it that way.’

‘I just did.’

‘It isn’t as if you were fond of Wilf. You weren’t. Anything but.’

‘You can get used to anything.’

‘Kelly ....’ Mrs Brown’s voice wavered. She didn’t know whether to try persuasion first, or threats. Both had so often failed. ‘Kelly, I hope you’ll be all right with... with Uncle Arthur. I mean I hope ...’

‘What do you mean “all right”?’

‘You know what I mean.’ Her voice had hardened. ‘I mean all right.’

‘Why shouldn’t I be all right with him?’

‘You tell me. I couldn’t see why you couldn’t get on with Wilf. He was good to you.’

‘He had no need to be.’

‘Kelly ....’

There was a yell from the passage. Arthur, still unfamiliar with the geography of the house, had gone through the hole in the floor.

He came in smiling nervously, anxious to appear at ease.

‘I’ll have to see if I can’t get that fixed for you, love.’

‘Arthur, this is my youngest, Kelly.’

He managed a smile. ‘Hello, flower.’

‘I don’t know what she’d better call you. Uncle Arthur?’

Kelly was twisting a roll of newspaper into a long rope. With a final wrench she got it finished and knotted the ends together to form a noose. Only when it was completed to her satisfaction did she smile and say, ‘Hello, Uncle Arthur.’

‘Well,’ said Mrs Brown, her voice edging upwards, ‘I’d better see what there is for breakfast.’

‘I can tell you now,’ said Kelly. ‘There’s nowt.’

Mrs Brown licked her lips. Then, in a refined voice, she said, ‘Oh, there’s sure to be something. Unless our Linda’s eat the lot.’

‘Our Linda’s eat nothing. She’s still in bed.’

‘Still in bed? What’s wrong with her?’

‘Day off. She says.’

‘Day off, my arse!’ The shock had restored Mrs Brown to her normal accent. ‘Linda!’ Her voice rose to a shriek. She ran upstairs. They could still hear her in the bedroom. Screaming fit to break the glass. If there’d been any left to break.

‘That’ll roust her!’ Arthur said, chuckling. He looked nice when he laughed. Kelly turned back to the fire, guarding herself from the temptation of liking him.

‘You’ve done a grand job,’ he said. ‘It’s not easy, is it, without sticks?’

‘I think it’ll go.’

After a few minutes Mrs Brown reappeared in the doorway. ‘I’m sorry about that, Arthur.’ She’d got her posh voice back on the way downstairs. ‘But if you didn’t keep on at them they’d be in bed all morning.’

She could talk!

‘Anyway, she’ll be down in a minute. Then you’ll have met both of them.’ She was trying to make it sound like a treat. Arthur didn’t look convinced. ‘While we’re waiting Kelly can go round the shop for a bit of bacon. Can’t you love?’

‘I’m doing the fire,’ Kelly pointed out in a voice that held no hope of compromise.

‘Don’t go getting stuff in just for me.’

‘Oh, it’s no bother. I can’t think how we’ve got so short.’ Sucking up again. Pretending to be what she wasn’t. And for what? He was nowt. ‘Anyway, we can’t have you going out with nothing on your stomach. You’ve got to keep your strength up.’ There was a secret, grown-up joke in her voice. Kelly heard it, and bristled.

‘She won’t let you have owt anyway,’ she said. ‘There’s over much on the slate as it is.’

Her mother rounded on her. ‘That’s right, Kelly, go on, stir the shit.’

‘I’m not stirring the shit. I’m just saying there’s too much on the slate.’

‘I’m paying for this, aren’t I?’

‘I dunno. Are you?’

Mrs Brown’s face was tight with rage and shame. Arthur had begun fumbling in his pockets for money. ‘Put that away, Arthur,’ she said quickly. ‘I’m paying.’

The door opened and Linda came in. ‘I can’t find me jumper,’ she said. She was naked except for a bra and pants.

‘It’ll be where you took it off.’

Linda shrugged. She wasn’t bothered. She turned her attention to the man. ‘Hello!’

‘My eldest. Linda.’

Arthur, his eyes glued to Linda’s nipples, opened and shut his mouth twice.

‘I think he’s trying to say “Hello”,’ Kelly said.

‘Thank you, Kelly. When we need an interpreter we’ll let you know.’ Mrs Brown was signalling to Linda to get dressed. Linda ignored her.

‘Is there a cup of tea?’ she asked.

Arthur’s hand caressed the warm curve of the pot.

‘There’s some in,’ he said. ‘I don’t know if it’s hot enough.’

‘Doesn’t matter. I can make fresh.’ She put one hand inside her bra and adjusted the position of her breast. Then she did the same for the other, taking her time about it. ‘Do you fancy a cup?’ she asked.

‘No, he doesn’t,’ said her mother. ‘He’s just had some upstairs.’

Mrs Brown looked suddenly older, rat-like, as her eyes darted between Arthur and the girl.

Kelly, watching, said, ‘I don’t know what you’re on about tea for, our Linda. If you’re late again you’re for the chop. And I don’t know who you’d get to give you another job. ’T’isn’t everybody fancies a filthy sod like you pawing at their food.’

‘Language!’ said Mrs Brown, automatically. She had almost given up trying to keep this situation under control. She would have liked to cry but from long habit held the tears back. ‘Kelly, outside in the passage. Now! Linda, get dressed.’

As soon as the living room door was closed, Mrs Brown whispered, ‘Now look, tell her half a pound of bacon, a loaf of bread – oh, and we’d better have a bottle of milk, and tell her here’s ten bob off the bill and I’ll give her the rest on Friday, without fail. Right?’

‘She won’t wear it.’

‘Well, do the best you can. Get the bacon anyway.’

Now that they were alone their voices were serious, almost friendly. Mrs Brown watched her daughter pulling on her anorak. ‘And Kelly,’ she said, ‘when you come back ...’

‘Yes?’

‘Try and be nice.’

The girl tossed her long hair out of her eyes like a Shetland pony. ‘Nice?’ she said. ‘I’m bloody marvellous!’

She went out, slamming the door.

‘... and a bar of chocolate, please.’ Kelly craned to see the sweets at the back of the counter. ‘I’ll have that one.’

‘Eightpence, mind.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘Does to me! Forty pence off the bill and eightpence for a bar of chocolate. I suppose you want the tuppence change?’

‘Yes, please.’

Grumbling to herself, Doris slapped the bar of chocolate down on the counter. ‘Sure there’s nowt else you fancy?’

‘I get hungry at school.’

‘Get that lot inside you, you won’t be.’ Doris indicated the bacon, milk and bread.

‘Oh, that’s not for me. That’s for her and her fancy man.’

‘But they’ll give you some?’

‘No they won’t.’

‘Eeeeee!’ Doris raised her eyes to the washing powder on the top shelf. ‘Dear God. You can tell your Mam if she’s not here by six o’clock Friday I’ll be up your street looking for her. And I won’t care who I show up neither.’

‘I’ll tell her. Thanks, Missus.’

After the child had gone Doris stationed herself on the doorstep hoping for somebody to share the outrage with. Her and her fancy man! Dear God!

A few minutes later her patience was rewarded. Iris King came round the corner, bare legs white and spotlessly clean, blonde hair bristling with rollers, obviously on her way to Mrs Bell’s.

She listened avidly.

‘Well,’ she said ‘I wish I could say I’m surprised, but if I did it’d be a lie. I saw her the other week sat round the Buffs with that Wilf Rogerson. I say nowt against him, it’s not his bairn – mind you, he’s rubbish – but her! They were there till past midnight and that bairn left to God and Providence. I know one thing, Missus, when my bairns were little they were never let roam the streets. And as for leave them on their own while I was pubbing it with a fella – no! By hell would I, not if his arse was decked with diamonds.’

‘And they don’t come like that, do they?’

‘They do not!’

Kelly, meanwhile, was eating a bacon butty.

‘Time you were thinking about school, our Kell.’

Kelly twisted round to look at the clock.

‘No use looking at that. It’s slow.’

‘Now she tells me!’

‘You knew. It’s always slow.’

Kelly wiped her mouth on the back of her hand and started to get up. ‘I’ll get the stick if I’m late again.’

‘They don’t give lasses the stick.’

‘They do, you know.’

‘Well, they didn’t when I was at school.’

‘Well, they do now.’

Kelly was really worried. She tried twice to zip up her anorak and each time failed.

‘And you can give your bloody mucky face a wipe. You’re not going out looking like that, showing me up.’

‘Oh, Mam, there isn’t time!’

‘You’ve time to give it a rub.’ She went into the kitchen and returned with a face flannel and tea towel. ‘Here, you’ll have to use this, I can’t find a proper towel.’

All this was Arthur’s fault. She’d never have bothered with breakfast or face-washing if he hadn’t been there. Kelly dabbed at the corners of her mouth, cautiously.

‘Go on, give it a scrub!’ Mrs Brown piled the breakfast dishes together and took them into the kitchen.

‘I’ll give you a hand,’ said Arthur.

‘No, it’s all right, love, I can manage. It won’t take a minute.’

It had been known to take days.

Arthur sat down, glancing nervously at Kelly. He was afraid of being alone with her. Kelly, looking at her reflection in the mirror, thought, how sensible of him.

‘Uncle Arthur?’ she said.

He looked up, relieved by the friendliness of her tone.

‘I was just wondering, are you and me Mam off round the Buffs tonight?’ As if she needed to ask!

‘I hadn’t really thought about it, flower. I daresay we might have a look in.’

‘It’s just there’s a film on at the Odeon: “Brides of Dracula”.’

‘Oh, I don’t think your Mam’ld fancy that.’

Why not? She’d fancied worse.

‘It wasn’t me Mam I was thinking of.’

‘Oh.’ He started searching in his pockets for money. Slower on the uptake than Wilf had been, but he got there in the end. He produced a couple of tenpenny pieces.

‘Cheapest seats are 50p.’

‘I thought it was kids half price?’

‘Not on Mondays. It’s Old Age Pensioners’ night.’

‘Oh, I see. They’re all sat there, are they, watching “Dracula”?’

‘Yeah, well. Gives ’em a thrill, don’t it?’

He wasn’t as thick as he looked.

‘Here’s a coupla quid. And get yourself summat to eat.’

‘Kelly! Are you still here?’

‘Just going, Mam.’ At the door she turned. ‘Will you be in when I get back?’

‘Don’t be daft. Arthur’s meeting me from work. Aren’t you, love?’ She smiled at him. Then became aware of the child watching her. ‘I don’t know when I’ll be in.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘There’s plenty to go at if you’re hungry. There’s that bit of bacon left. And you’re old enough to get yourself to bed.’

‘I said, it doesn’t matter.’

The door slammed.

Kelly stared across the blackening school yard. The windows of the school were encased in wire cages: the children threw bricks. Behind the wire the glass had misted over, become a sweaty blur through which the lights of the Assembly Hall shone dimly.

There was a ragged sound of singing.

‘New every morning is the love

Our wakening and uprising prove ...’

If she went in as late as this she might well get the stick. Safer, really, to give school a miss. She could easily write a note tomorrow in her mother’s handwriting. She had done it before.

There was a fair on, too, on the patch of waste ground behind the park. She hesitated, felt the crisp pound notes in her pocket, and made up her mind.

She ran into the railway tunnel, her footsteps echoing dismally behind her.

She wandered down a long avenue of trees, scuffling through the dead leaves. Horse chestnut leaves, she realised, like hands with spread fingers. Immediately she began to look at the ground more closely, alert for the gleam of conkers in the grass.

It was too early though – only the beginning of September. They would not have ripened yet.

The early excitement of nicking off from school was gone. She was lonely. The afternoon had dragged. There was a smell of decay, of life ending. Limp rags of mist hung from the furthest trees.

As always when she was most unhappy, she started thinking about her father, imagining what it would be like when he came back home. She was always looking for him, expecting to meet him, though sometimes, in moments of panic and despair, she doubted if she would recognise him if she did.

There was only one memory she was sure of. Firelight. The smells of roast beef and gravy and the News of the World, and her father with nothing on but his vest and pants, throwing her up into the air again and again. If she closed her eyes she could see his warm and slightly oily brown skin and the snake on his arm that wriggled when he clenched the muscle underneath.

She was sure of that. Though the last time she had tried to talk to Linda about it, Linda had said ... had said ... Well, it didn’t matter what Linda said.

Absorbed in her daydreams, she had almost missed it. But there it lay, half-hidden in the grass. It wasn’t open, though. She bent down, liking the feel of the cool, green, spiky ball in her hand.

She had heard nothing, and yet there in front of her were the feet, shoes black and highly polished, menacingly elegant against the shabbiness of leaves and grass.

Slowly she looked up. He was tall and thin with a long head, so that she seemed from her present position to be looking up at a high tower.

‘You found one then?’

She knew from the way he said it that he had been watching her a long time.

‘Yes,’ she said, standing up. ‘But it’s not ready yet.’

‘Oh, I don’t know. Sometimes they are. You can’t always tell from the outside.’

He took it from her. She watched his long fingers with their curved nails probe the green skin, searching for the place where it would most easily open and admit them.

‘Though everything’s a bit late this year. I think it must be all the rain we’ve been having.’

She didn’t want to watch. Instead she glanced rapidly from side to side, wishing she’d stayed near the railings where at least there might have been people walking past on the pavement outside.

There was nobody in sight.

When she looked back he had got the conker open. Through the gash in the green skin she could see the white seed.

‘No, you were right,’ he said. ‘It’s not ready yet.’

He threw it away and wiped his fingers very carefully and fastidiously on his handkerchief, as if they were more soiled than they could possibly have been.

‘I’ve got some more,’ he said, suddenly. ‘You can have them to take home if you like.’ He reached into his pockets and produced a mass of conkers, a dozen or more, and held them out to her on the palms of his cupped hands. She looked at them doubtfully. ‘Go on, take them,’ he said.

His voice shook with excitement.

Kelly took them, hoping that if she did as he said he would go away. But he showed no sign of wanting to go.

‘What’s your name?’ he asked. He had a precise, slightly sibilant way of speaking that might’ve been funny, but wasn’t.

‘Kelly,’ she said.

‘Kelly. That’s an unusual name.’

Kelly shrugged. It wasn’t particularly unusual where she came from.

‘And does your mother know you’re here, Kelly? I mean, shouldn’t you be at school?’

‘I’ve had the flu. She said, Go and get some fresh air.’

Normally she was a very convincing liar. But uncertainty had robbed her of the skill and her words clattered down, as unmistakably empty as tin cans.

He smiled. ‘I see. How sensible of her to let you come out. Much better than staying indoors.’

He had accepted the lie without believing it. Kelly shivered and looked longingly towards the road. She would have liked to turn and walk away from him, just like that, without explanation, without leave-taking. But she could not. He had done nothing, said nothing, wrong; and there was something in the softness of his voice that compelled her to stay.

‘I’ve been ill too,’ he said. ‘That’s why I’m not at work.’

And perhaps he had. He looked pale enough for anything. ‘Well, I think . . .

Kelly Brown, disturbed by the noise, turned over, throwing one arm across her sister’s face.

The older girl stirred in her sleep, grumbling a little through dry lips, and then, abruptly, woke.

‘I wish you’d watch what you’re doing. You nearly had my eye out there.’

Kelly opened her eyes, reluctantly. She lay in silence for a moment trying to identify the sound that had disturbed her. ‘It’s that thing,’ she said, finally. ‘It’s that bloody cardboard. It’s come unstuck.’

‘That wouldn’t be there either if you’d watch what you’re doing.’

‘Oh, I see. My fault. I suppose you weren’t there when it happened?’

Linda had pulled the bedclothes over her head. Kelly waited a moment, then jabbed her in the kidneys. Hard.

‘Time you were up.’ Outside, a man’s boots slurred over the cobbles: the first shift of the day. ‘You’ll be late.’

‘What’s it to you?’

‘You’ll get the sack.’

‘No, I won’t then, clever. Got the day off, haven’t I?’

‘I don’t know. Have you?’

No reply. Kelly was doubled up under the sheet, her body jack-knifed against the cold. As usual, Linda had pinched most of the blankets and all the eiderdown.

‘Well, have you?’

‘Cross me heart and hope to die, cut me throat if I tell a lie.’

‘Jammy bugger!’

‘I don’t mind turning out.’

‘Not much!’

‘You’ve nothing to turn out to.’

‘School.’

‘School!’

‘I didn’t notice you crying when you had to leave.’

Kelly abandoned the attempt to keep warm. She sat on the edge of the bed, sandpapering her arms with the palms of dirty hands. Then ran across the room to the chest of drawers.

As she pulled open the bottom drawer – the only one Linda would let her have – a characteristic smell met her.

‘You mucky bloody sod!’ The cold forgotten, she ran back to the bed and began dragging the blankets off her sister. ‘Why can’t you burn the buggers?’

‘With him sat there? How can I?’

Both girls glanced at the wall that divided their mother’s bedroom from their own. For a moment Kelly’s anger died down.

Then: ‘He wasn’t there last night.’

‘There was no fire.’

‘You could’ve lit one.’

‘What? At midnight? What do you think she’d say about that?’ Linda jerked her head towards the intervening wall.

‘Well, you could’ve wrapped them up and put them in the dustbin then. Only the lowest of the bloody low go on the way you do.’

‘What would you know about it?’

‘I know one thing, I’ll take bloody good care I never get like it.’

‘You will, dear. It’s nature.’

‘I don’t mean that.’

Though she did, perhaps. She looked at the hair in Linda’s armpits, at the breasts that shook and wobbled when she ran, and no, she didn’t want to get like that. And she certainly didn’t want to drip foul-smelling, brown blood out of her fanny every month. ‘Next one I find I’ll rub your bloody mucky face in.’

‘You and who else?’

‘It won’t need anybugger else.’

‘You! You’re not the size of twopenn’orth of copper.’

‘See if that stops me.’

There was a yell from the next bedroom. ‘For God’s sake, you two, shut up! There’s some of us still trying to sleep.’

‘No bloody wonder. On the hump all night.’

‘Linda!’

‘Notice she blames me. You’re getting to be a right cheeky little sod, you are.’

‘Did you hear me, Linda?’

‘Just watch it, that’s all.’

‘Linda!’

‘I’ll tell Kevin about you,’ Kelly said. ‘He wouldn’t be so keen getting his hand up if he knew what you were really like.’

‘Have I to come in there?’

The threat silenced both girls. With a final glare Kelly picked up her clothes and went downstairs to get dressed. On the landing she paused to look into her mother’s bedroom. There was a dark, bearded man zipping up his trousers. When he saw her his face twitched as if he wanted to smile. It wasn’t Wilf. It was a man she had never seen before.

She ran all the way downstairs, remembering, though only just in time, to jump over the hole in the passage where the floorboards had given way.

Dressed, she turned her attention to the fire. Since there were no sticks, she would have to try to light it on paper alone, a long and not always successful job. Muttering to herself, she reached up and pulled one of her mother’s sweaters from the airing line. There were sweaters of her own and Linda’s there but she liked her mother’s better. They were warmer, somehow, and she liked the smell.

She picked up the first sheet of newspaper. The face of a young soldier killed in Belfast disappeared beneath her scrumpling fingers. Then her mother came in, barefoot, wearing only a skirt and bra. The bunions on the sides of her feet were red with cold.

She was still angry. Or on the defensive. Kelly could tell at once by the way she moved.

‘I see you’ve nicked another of me sweaters. Beats me why you can’t wear your own. You’d think you had nowt to put on.’

She searched along the line and pulled down her old working jumper that had gone white under the armpits from deodorants and sweat. After a moment’s thought she rejected it in favour of a blue blouse, the sort of thing she would never normally have worn at work. It was because of him, the man upstairs.

Kelly sniffed hungrily at the sweater she was wearing, which held all the mingled smells of her mother’s body. Though the face she raised to her mother afterwards could not have been more hostile.

‘You got started on the fire, then? Good lass.’

‘I’d ’ve had it lit if there’d been owt to light it with.’

‘Yes, well, I forgot the sticks.’

She perched on the edge of the armchair and began pulling on her tights. Kelly watched. She went on twisting rolls of newspaper, the twists becoming more vicious as the silence continued.

At last she said, ‘Well, come on, then. Don’t keep us in suspense. Who is it?’

‘Who?’

Kelly drew a deep breath. ‘Him. Upstairs. The woolly-faced bugger with the squint.’

‘His name’s Arthur. And he doesn’t squint.’

‘He was just now when he looked at me.’

‘Oh, you’d make any bugger squint, you would!’

‘Does that mean Wilf’s had his chips?’

‘You could put it that way.’

‘I just did.’

‘It isn’t as if you were fond of Wilf. You weren’t. Anything but.’

‘You can get used to anything.’

‘Kelly ....’ Mrs Brown’s voice wavered. She didn’t know whether to try persuasion first, or threats. Both had so often failed. ‘Kelly, I hope you’ll be all right with... with Uncle Arthur. I mean I hope ...’

‘What do you mean “all right”?’

‘You know what I mean.’ Her voice had hardened. ‘I mean all right.’

‘Why shouldn’t I be all right with him?’

‘You tell me. I couldn’t see why you couldn’t get on with Wilf. He was good to you.’

‘He had no need to be.’

‘Kelly ....’

There was a yell from the passage. Arthur, still unfamiliar with the geography of the house, had gone through the hole in the floor.

He came in smiling nervously, anxious to appear at ease.

‘I’ll have to see if I can’t get that fixed for you, love.’

‘Arthur, this is my youngest, Kelly.’

He managed a smile. ‘Hello, flower.’

‘I don’t know what she’d better call you. Uncle Arthur?’

Kelly was twisting a roll of newspaper into a long rope. With a final wrench she got it finished and knotted the ends together to form a noose. Only when it was completed to her satisfaction did she smile and say, ‘Hello, Uncle Arthur.’

‘Well,’ said Mrs Brown, her voice edging upwards, ‘I’d better see what there is for breakfast.’

‘I can tell you now,’ said Kelly. ‘There’s nowt.’

Mrs Brown licked her lips. Then, in a refined voice, she said, ‘Oh, there’s sure to be something. Unless our Linda’s eat the lot.’

‘Our Linda’s eat nothing. She’s still in bed.’

‘Still in bed? What’s wrong with her?’

‘Day off. She says.’

‘Day off, my arse!’ The shock had restored Mrs Brown to her normal accent. ‘Linda!’ Her voice rose to a shriek. She ran upstairs. They could still hear her in the bedroom. Screaming fit to break the glass. If there’d been any left to break.

‘That’ll roust her!’ Arthur said, chuckling. He looked nice when he laughed. Kelly turned back to the fire, guarding herself from the temptation of liking him.

‘You’ve done a grand job,’ he said. ‘It’s not easy, is it, without sticks?’

‘I think it’ll go.’

After a few minutes Mrs Brown reappeared in the doorway. ‘I’m sorry about that, Arthur.’ She’d got her posh voice back on the way downstairs. ‘But if you didn’t keep on at them they’d be in bed all morning.’

She could talk!

‘Anyway, she’ll be down in a minute. Then you’ll have met both of them.’ She was trying to make it sound like a treat. Arthur didn’t look convinced. ‘While we’re waiting Kelly can go round the shop for a bit of bacon. Can’t you love?’

‘I’m doing the fire,’ Kelly pointed out in a voice that held no hope of compromise.

‘Don’t go getting stuff in just for me.’

‘Oh, it’s no bother. I can’t think how we’ve got so short.’ Sucking up again. Pretending to be what she wasn’t. And for what? He was nowt. ‘Anyway, we can’t have you going out with nothing on your stomach. You’ve got to keep your strength up.’ There was a secret, grown-up joke in her voice. Kelly heard it, and bristled.

‘She won’t let you have owt anyway,’ she said. ‘There’s over much on the slate as it is.’

Her mother rounded on her. ‘That’s right, Kelly, go on, stir the shit.’

‘I’m not stirring the shit. I’m just saying there’s too much on the slate.’

‘I’m paying for this, aren’t I?’

‘I dunno. Are you?’

Mrs Brown’s face was tight with rage and shame. Arthur had begun fumbling in his pockets for money. ‘Put that away, Arthur,’ she said quickly. ‘I’m paying.’

The door opened and Linda came in. ‘I can’t find me jumper,’ she said. She was naked except for a bra and pants.

‘It’ll be where you took it off.’

Linda shrugged. She wasn’t bothered. She turned her attention to the man. ‘Hello!’

‘My eldest. Linda.’

Arthur, his eyes glued to Linda’s nipples, opened and shut his mouth twice.

‘I think he’s trying to say “Hello”,’ Kelly said.

‘Thank you, Kelly. When we need an interpreter we’ll let you know.’ Mrs Brown was signalling to Linda to get dressed. Linda ignored her.

‘Is there a cup of tea?’ she asked.

Arthur’s hand caressed the warm curve of the pot.

‘There’s some in,’ he said. ‘I don’t know if it’s hot enough.’

‘Doesn’t matter. I can make fresh.’ She put one hand inside her bra and adjusted the position of her breast. Then she did the same for the other, taking her time about it. ‘Do you fancy a cup?’ she asked.

‘No, he doesn’t,’ said her mother. ‘He’s just had some upstairs.’

Mrs Brown looked suddenly older, rat-like, as her eyes darted between Arthur and the girl.

Kelly, watching, said, ‘I don’t know what you’re on about tea for, our Linda. If you’re late again you’re for the chop. And I don’t know who you’d get to give you another job. ’T’isn’t everybody fancies a filthy sod like you pawing at their food.’

‘Language!’ said Mrs Brown, automatically. She had almost given up trying to keep this situation under control. She would have liked to cry but from long habit held the tears back. ‘Kelly, outside in the passage. Now! Linda, get dressed.’

As soon as the living room door was closed, Mrs Brown whispered, ‘Now look, tell her half a pound of bacon, a loaf of bread – oh, and we’d better have a bottle of milk, and tell her here’s ten bob off the bill and I’ll give her the rest on Friday, without fail. Right?’

‘She won’t wear it.’

‘Well, do the best you can. Get the bacon anyway.’

Now that they were alone their voices were serious, almost friendly. Mrs Brown watched her daughter pulling on her anorak. ‘And Kelly,’ she said, ‘when you come back ...’

‘Yes?’

‘Try and be nice.’

The girl tossed her long hair out of her eyes like a Shetland pony. ‘Nice?’ she said. ‘I’m bloody marvellous!’

She went out, slamming the door.

‘... and a bar of chocolate, please.’ Kelly craned to see the sweets at the back of the counter. ‘I’ll have that one.’

‘Eightpence, mind.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘Does to me! Forty pence off the bill and eightpence for a bar of chocolate. I suppose you want the tuppence change?’

‘Yes, please.’

Grumbling to herself, Doris slapped the bar of chocolate down on the counter. ‘Sure there’s nowt else you fancy?’

‘I get hungry at school.’

‘Get that lot inside you, you won’t be.’ Doris indicated the bacon, milk and bread.

‘Oh, that’s not for me. That’s for her and her fancy man.’

‘But they’ll give you some?’

‘No they won’t.’

‘Eeeeee!’ Doris raised her eyes to the washing powder on the top shelf. ‘Dear God. You can tell your Mam if she’s not here by six o’clock Friday I’ll be up your street looking for her. And I won’t care who I show up neither.’

‘I’ll tell her. Thanks, Missus.’

After the child had gone Doris stationed herself on the doorstep hoping for somebody to share the outrage with. Her and her fancy man! Dear God!

A few minutes later her patience was rewarded. Iris King came round the corner, bare legs white and spotlessly clean, blonde hair bristling with rollers, obviously on her way to Mrs Bell’s.

She listened avidly.

‘Well,’ she said ‘I wish I could say I’m surprised, but if I did it’d be a lie. I saw her the other week sat round the Buffs with that Wilf Rogerson. I say nowt against him, it’s not his bairn – mind you, he’s rubbish – but her! They were there till past midnight and that bairn left to God and Providence. I know one thing, Missus, when my bairns were little they were never let roam the streets. And as for leave them on their own while I was pubbing it with a fella – no! By hell would I, not if his arse was decked with diamonds.’

‘And they don’t come like that, do they?’

‘They do not!’

Kelly, meanwhile, was eating a bacon butty.

‘Time you were thinking about school, our Kell.’

Kelly twisted round to look at the clock.

‘No use looking at that. It’s slow.’

‘Now she tells me!’

‘You knew. It’s always slow.’

Kelly wiped her mouth on the back of her hand and started to get up. ‘I’ll get the stick if I’m late again.’

‘They don’t give lasses the stick.’

‘They do, you know.’

‘Well, they didn’t when I was at school.’

‘Well, they do now.’

Kelly was really worried. She tried twice to zip up her anorak and each time failed.

‘And you can give your bloody mucky face a wipe. You’re not going out looking like that, showing me up.’

‘Oh, Mam, there isn’t time!’

‘You’ve time to give it a rub.’ She went into the kitchen and returned with a face flannel and tea towel. ‘Here, you’ll have to use this, I can’t find a proper towel.’

All this was Arthur’s fault. She’d never have bothered with breakfast or face-washing if he hadn’t been there. Kelly dabbed at the corners of her mouth, cautiously.

‘Go on, give it a scrub!’ Mrs Brown piled the breakfast dishes together and took them into the kitchen.

‘I’ll give you a hand,’ said Arthur.

‘No, it’s all right, love, I can manage. It won’t take a minute.’

It had been known to take days.

Arthur sat down, glancing nervously at Kelly. He was afraid of being alone with her. Kelly, looking at her reflection in the mirror, thought, how sensible of him.

‘Uncle Arthur?’ she said.

He looked up, relieved by the friendliness of her tone.

‘I was just wondering, are you and me Mam off round the Buffs tonight?’ As if she needed to ask!

‘I hadn’t really thought about it, flower. I daresay we might have a look in.’

‘It’s just there’s a film on at the Odeon: “Brides of Dracula”.’

‘Oh, I don’t think your Mam’ld fancy that.’

Why not? She’d fancied worse.

‘It wasn’t me Mam I was thinking of.’

‘Oh.’ He started searching in his pockets for money. Slower on the uptake than Wilf had been, but he got there in the end. He produced a couple of tenpenny pieces.

‘Cheapest seats are 50p.’

‘I thought it was kids half price?’

‘Not on Mondays. It’s Old Age Pensioners’ night.’

‘Oh, I see. They’re all sat there, are they, watching “Dracula”?’

‘Yeah, well. Gives ’em a thrill, don’t it?’

He wasn’t as thick as he looked.

‘Here’s a coupla quid. And get yourself summat to eat.’

‘Kelly! Are you still here?’

‘Just going, Mam.’ At the door she turned. ‘Will you be in when I get back?’

‘Don’t be daft. Arthur’s meeting me from work. Aren’t you, love?’ She smiled at him. Then became aware of the child watching her. ‘I don’t know when I’ll be in.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘There’s plenty to go at if you’re hungry. There’s that bit of bacon left. And you’re old enough to get yourself to bed.’

‘I said, it doesn’t matter.’

The door slammed.

Kelly stared across the blackening school yard. The windows of the school were encased in wire cages: the children threw bricks. Behind the wire the glass had misted over, become a sweaty blur through which the lights of the Assembly Hall shone dimly.

There was a ragged sound of singing.

‘New every morning is the love

Our wakening and uprising prove ...’

If she went in as late as this she might well get the stick. Safer, really, to give school a miss. She could easily write a note tomorrow in her mother’s handwriting. She had done it before.

There was a fair on, too, on the patch of waste ground behind the park. She hesitated, felt the crisp pound notes in her pocket, and made up her mind.

She ran into the railway tunnel, her footsteps echoing dismally behind her.

She wandered down a long avenue of trees, scuffling through the dead leaves. Horse chestnut leaves, she realised, like hands with spread fingers. Immediately she began to look at the ground more closely, alert for the gleam of conkers in the grass.

It was too early though – only the beginning of September. They would not have ripened yet.

The early excitement of nicking off from school was gone. She was lonely. The afternoon had dragged. There was a smell of decay, of life ending. Limp rags of mist hung from the furthest trees.

As always when she was most unhappy, she started thinking about her father, imagining what it would be like when he came back home. She was always looking for him, expecting to meet him, though sometimes, in moments of panic and despair, she doubted if she would recognise him if she did.

There was only one memory she was sure of. Firelight. The smells of roast beef and gravy and the News of the World, and her father with nothing on but his vest and pants, throwing her up into the air again and again. If she closed her eyes she could see his warm and slightly oily brown skin and the snake on his arm that wriggled when he clenched the muscle underneath.

She was sure of that. Though the last time she had tried to talk to Linda about it, Linda had said ... had said ... Well, it didn’t matter what Linda said.

Absorbed in her daydreams, she had almost missed it. But there it lay, half-hidden in the grass. It wasn’t open, though. She bent down, liking the feel of the cool, green, spiky ball in her hand.

She had heard nothing, and yet there in front of her were the feet, shoes black and highly polished, menacingly elegant against the shabbiness of leaves and grass.

Slowly she looked up. He was tall and thin with a long head, so that she seemed from her present position to be looking up at a high tower.

‘You found one then?’

She knew from the way he said it that he had been watching her a long time.

‘Yes,’ she said, standing up. ‘But it’s not ready yet.’

‘Oh, I don’t know. Sometimes they are. You can’t always tell from the outside.’

He took it from her. She watched his long fingers with their curved nails probe the green skin, searching for the place where it would most easily open and admit them.

‘Though everything’s a bit late this year. I think it must be all the rain we’ve been having.’

She didn’t want to watch. Instead she glanced rapidly from side to side, wishing she’d stayed near the railings where at least there might have been people walking past on the pavement outside.

There was nobody in sight.

When she looked back he had got the conker open. Through the gash in the green skin she could see the white seed.

‘No, you were right,’ he said. ‘It’s not ready yet.’

He threw it away and wiped his fingers very carefully and fastidiously on his handkerchief, as if they were more soiled than they could possibly have been.

‘I’ve got some more,’ he said, suddenly. ‘You can have them to take home if you like.’ He reached into his pockets and produced a mass of conkers, a dozen or more, and held them out to her on the palms of his cupped hands. She looked at them doubtfully. ‘Go on, take them,’ he said.

His voice shook with excitement.

Kelly took them, hoping that if she did as he said he would go away. But he showed no sign of wanting to go.

‘What’s your name?’ he asked. He had a precise, slightly sibilant way of speaking that might’ve been funny, but wasn’t.

‘Kelly,’ she said.

‘Kelly. That’s an unusual name.’

Kelly shrugged. It wasn’t particularly unusual where she came from.

‘And does your mother know you’re here, Kelly? I mean, shouldn’t you be at school?’

‘I’ve had the flu. She said, Go and get some fresh air.’

Normally she was a very convincing liar. But uncertainty had robbed her of the skill and her words clattered down, as unmistakably empty as tin cans.

He smiled. ‘I see. How sensible of her to let you come out. Much better than staying indoors.’

He had accepted the lie without believing it. Kelly shivered and looked longingly towards the road. She would have liked to turn and walk away from him, just like that, without explanation, without leave-taking. But she could not. He had done nothing, said nothing, wrong; and there was something in the softness of his voice that compelled her to stay.

‘I’ve been ill too,’ he said. ‘That’s why I’m not at work.’

And perhaps he had. He looked pale enough for anything. ‘Well, I think . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved