- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

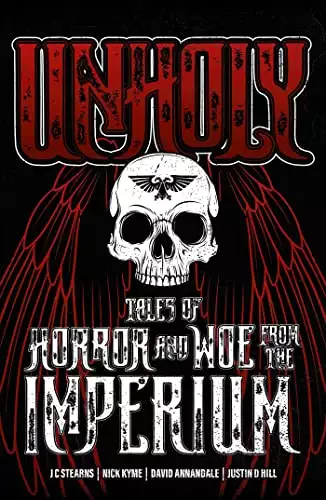

Synopsis

Spine-chilling stories from the rich Worlds of Warhammer.

Amid the bloody wars, cults and tyrants of the Imperium, a far quieter horror lurks. Valgaast is an entity that compels and corrupts. Darker than the pits of hell, incomprehensible as death, it seeps into the hearts and minds of those weakened by misfortune.

A premature heiress grieving the loss of her family. A bleak man of faith with unquenchable desires. A woman whose broken memories replay terrible violence. A little town left to rot in a sun-scorched wasteland. In this chilling collection of Warhammer Horror fiction, Valgaast claims the victims of this vast and lonely universe, and, with malicious intent, pushes them to their limits.

This omnibus edition collects together the novels The Oubliette by J C Stearns, Sepulturum by Nick Kyme, The Deacon of Wounds by David Annandale and The Bookkeeper’s Skull by Justin D Hill.

Release date: February 14, 2023

Publisher: Warhammer Horror

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Unholy: Tales of Horror and Woe from the Imperium

Various

CHAPTER 1

The tolling of the church bells was truly breathtaking. Even through her haze of grief, Ashielle could appreciate the labour that had to have gone into the Toll of Mourning for her father.

All across Kostoveim, from cobbled streets to arched, embellished spires, the bells rang out for Governor Ruprekt Matkosen. Every bell in every cathedral, shrine and watchtower across Ceocan pealed at once, each rolling cry sounding perfectly in unison. After each ring, a brief pause followed to let the reverberations fade, to let each citizen of the planet appreciate the profound silence. Then the bells were struck again. Ashielle was grateful to the priests and clergy who had spent so much time coordinating the Toll of Mourning, ensuring that the timing of each ring was perfect as far as her ear could detect. She had never before heard the bells so coordinated. Even at the most sombre of state funerals, as long ago as she could recall, she could always remember hearing one cathedral out of sync. Of course, she’d never attended the funeral of a governor before. Very few of the people living on Ceocan had.

Certainly, none of those massed beyond the gates of the Augusta Korgana, the grand graveyard of the planet’s most venerated dead, had ever seen such a thing. Thousands of citizens had come out to pay their respects. It lifted her spirit to see so many people moved by their loyalty to Ruprekt, that they would face the cold, drizzling rain to stand in solidarity with her family. The noble families, the Adeptus masters, the other dignitaries whose stations and accolades demanded they be admitted inside the gates of the Korgana: they attended to be seen attending. They marched solemnly through the gravestones, cenotaphs and raised sarcophagi, shielded from the chill shower by wide, robust hoods, or beneath engraved and embroidered umbrellas held by numb and shivering servants. They bowed their heads to Ashielle, of course, mouthing platitudes or quoting bits of scripture which were meant to give her comfort. Always, of course, they maintained their dignity and composure, never allowing themselves to act as though this were anything more than a formality.

Beyond the wrought iron fencing, thinly threaded with rose canes, the populace of Kostoveim pressed in, clad in mourning black, their faces daubed with grey ashes. Their emotional displays were raw in their honesty, with many older serfs weeping openly and grasping at the Korgana fences, uncaring hands bloody against the thorns of the roses. When Ruprekt Matkosen’s body was drawn from the hearse, draped in its white shroud and adorned with the golden aquila, Ashielle could hear several voices from the gathered throng of commoners wailing in anguish. Truthfully, she drew more solace from their intense grieving than she did the perfunctory performances of the elite gathered near to her.

She remembered standing in the Korgana Ecclesiastia as a child, when the venerable Deacon Yasoven had passed. The pious had journeyed from all across Ceocan to pay their respects. The crowd hadn’t been half the size of that gathered for Governor Matkosen, but it was the largest state funeral she could recall. Then, as now, the gathered throngs wept and tore at their hair, the intensity of their mourning inversely proportional to their social rank. Ashielle had marvelled at the lives that the aged deacon had touched in his time on Ceocan.

‘He visited no great evil on their homes,’ her father had told her, ‘and placed no burdens upon their shoulders too great for them to bear.’ The planetary governor had seemed so tall and strong to her, as a child. His broad shoulders seemed stout enough to bear the grief of the entire household. Only she and Geordan were permitted to stand close enough to him to see the dampness beneath his eyes.

‘For most of humanity, that is all that is required for the foundation of a great leader. Given enough time, that simple basis can become the foundation of their whole lives.’ Ruprekt had given the slightest of nods then, to the crowd of wailing mourners. ‘After such a tenure as the deacon had, losing him is like waking to discover that a mountain has vanished, or a moon has fallen from the sky. They weep not because they have lost a friend or a loved one – instead they weep because a cornerstone of their world is missing, and now for them everything is uncertain.’ The governor turned his unyielding gaze to his two children, his marble grey eyes boring into them over his thick, bushy moustache. ‘The onus of stability falls to us. In this time of uncertainty, the governor must be the rock upon which the entire planet may anchor themselves. Do you understand?’

The enormity of the responsibility that might one day be hers had borne down on her, then. Geordan had reached out and taken her hand in his when Ruprekt turned away. She remembered smiling up at him, grateful for his support. She wished Geordan could be with her now, for she could use that manner of comfort again. Thinking of her elder brother brought a spike of grief of a different kind, one mixed with shame. His own funeral had been several days prior, and had been far smaller in scale, of course.

Ruprekt’s words had been prescient. If the deacon’s death was akin to the loss of one of Ceocan’s four moons, then Ruprekt’s had been as though the citizens had gazed up at noon and seen the sun explode. When the deacon had gone to the Throne, it had been a shock, but not an unexpected one. Deacon Yasoven had been nearing his fourth century when his body had finally failed. Ruprekt Matkosen had been much greater in importance than the deacon, and there had been no emotional preparation for his passing. The accident had seen to that.

As the bells continued their droning memorial, ringing out one toll for each of the one hundred and twelve years of Ruprekt Matkosen’s life, Ashielle felt a moment of true grief creeping into her throat. Hot tears threatened her eyes. She knew how the assembled crowd felt: Ruprekt should have governed them for decades to come. She was only thirty-three, far younger than anyone had ever thought Ruprekt’s heir would be when they ascended.

The mourners inside the iron barricades did not wail: they whispered. Out of the corners of their mouths and behind delicate fans, Ashielle knew they were murmuring. It wasn’t a sound she could hear; it was a sensation she could feel.

She spied the narrow shoulders of Langreve Oldemeier. He was leaning close – literally rubbing shoulders with Margreve Tianesh Bruisell. They huddled together, he in his jet-black suit with his raven hair, she in a charcoal mourning coat, the lace collar webbed across her throat, looking the very picture of young lovers sharing an umbrella on a rainy day. Ashielle knew better. Before he was the Langreve of his house, Uri Oldemeier had counselled Ashielle’s father to send her away to the schola rather than her brother, Hanrik. Despite her cherubic features and youthful complexion, Lady Bruisell was over one hundred and thirty, and Ashielle had heard her make remarks before, indicating her feelings that no one younger than a century should serve in any real leadership position. From a distance, their closeness could be mistaken for support and comfort in a time of sorrow, but Ashielle knew veteran politicians such as they would be whispering about some political manoeuvring which would benefit them both.

The bells ended, and a dreadful silence washed over the Korgana, drawing Ashielle back to the present. Deacon Phoebian placed a hand on the shroud covering Governor Matkosen. Former Governor Matkosen, Ashielle corrected herself. No one who spoke of Governor Matkosen was referring to her father any longer. Now that honour belonged to her, whether she wished it or not. The aged deacon held one hand out towards her.

Ashielle grabbed Hanrik’s hand and squeezed it for support as she stepped forward. Her brother allowed her to take his hand, but did not return her gesture. He seemed to have no need for her support, and no solace to give to her in return. If the gathered nobles and adepts were reserved, he was positively mechanical. The hooded saints carved in stone looming from the cenotaphs offered more succour than she saw in his unyielding face.

The other nobles she passed on her path to the deacon were no warmer. They had come to the Korgana dutifully, but like her brother, they had no comfort for her. Each of them offered kind words, of course, but not to lift her up or ease her burden. The heads of the planetary organisations, like Magos Crofeld, Adept Sheng and Master Trulanthion, attended because they had an obligation to do so. Like General Zhevan and the deacon herself, they came because they understood that the projection of stability they were obligated to show required them to be seen supporting her in this time of transition. The lesser nobles of the Grevenate offered her their verbal tokens as well, not that they had any desire to support her, either. Each hoped that somehow their paltry attempt at succour would be remembered when they came calling, as if they could buy political favour with a sad expression and a mumbled platitude.

Her servants followed behind her, but she gestured them away, taking a single umbrella from an elderly attendant, who released the handle from her icy fingers with relief. Ashielle held the canopy overhead and walked the final lengths to her father’s open sarcophagus alone. She collapsed the umbrella before kneeling on the prayer bench before the deacon. Let the mourners see her walking in the rain, enduring the cold and the damp for a few moments with no more protection than they had. From the street, she would be easy to pick out. Among the mourners, even those of means and noble bearing, she alone wore white, her pale gown and veil marking her as the head of House Matkosen and sole entrusted governor of Ceocan.

Deacon Phoebian placed her withered hand on Ashielle’s head, muttering whispered scriptures under her breath. In years long past, the spiritual head of the community would preside at state funerals, ritualistically serving as a conduit to pass the divine right of rulership from one liege to another. Now, of course, the action was entirely symbolic. The senior adepts had borne witness to her official ascension weeks ago, within hours of her father’s untimely passing.

Ashielle stood as Deacon Phoebian finished her liturgy, and drew the veil from her face. She let the cold rain wash over her features for a moment, taking a pause to appreciate the gravity of her last moments, symbolic or not, with her father’s presence. Then she placed her veil in Ruprekt’s sarcophagus, draped over his shrouded remains.

She stepped away, and the Ministorum servitors approached. They had the appearance of men, albeit hulking ones, naked save for a black tabard emblazoned with the image of the cathedral. Each wore a bronze mask, wrought in the shape of a bull’s head, to keep the public from seeing their slack-jawed, hollow-eyed visages. To the public they might be mighty, miraculous warriors of the church, but Ashielle knew their sorry nature. She knew, too, that little of human flesh remained to them, mostly pale skin stretched over their corded hydraulic musculature, and a lobotomised brain and spinal cord to coordinate the industrial machinery contained in their frames.

The two servitors lifted the lid of Ruprekt Matkosen’s sarcophagus, adorned with an image of the late lord governor kneeling in piety towards the Grand Cathedral, leaning against a sword, his forehead resting against the pommel. The servitors lowered the lid with a delicacy their forms would not seem to possess.

The sombre thump of the stone lid sliding home echoed in Ashielle’s mind. She would remember it more clearly than the tolling of the bells or the wailing of the mourners. That booming, earthen sound was the end of everything that had come before: there could be no denying now that she was the governor of Ceocan.

They came in ones and twos: the nobles and functionaries wishing her well or expressing a tearful reminder of how close they had felt to the late Governor Matkosen. Most of the words were hollow and meaningless, of course, but she smiled and thanked them nonetheless. More gratifying were the few nobles who seemed genuine in their grief. Paola Gavozny, who had been a fellow scholar at Trenkovi University with her when she had studied Artistic Legacy of Imperial Societies. Liana Chole, the daughter of Greve Chole, who Ruprekt had saved from bankruptcy with a generous loan which had become a gift, had honest tears in her eyes, which nearly moved Ashielle to the same. When the line of mourners finally came to Langreve Evanova, who had attended the capital’s elite schola with Ruprekt and with whom he had shared a fondness for aged amasec and fine Ystrodian cigars, the old man had become choked and unable to form a single word. He had just nodded, gripping Ashielle’s hand tightly, before his wife had put a hand on his shoulder and led him away.

There were a great many people who wished at last to express their condolences to her, now that they had an opportunity to be seen in public doing so. Lesser noble scions, heads of august and aged families, wealthy merchant captains: she knew all of them from years of careful briefings, which had been the subject of her renewed interest over the past few weeks. She knew which ones owed her family favours, which ones lusted for greater power, which ones were bound together by their own bonds of loyalty. So when a small man she did not recognise stepped forward, it was something of a mild surprise.

There were a great many aspects of the management of an entire planet to which Ashielle remained ignorant, and which she anticipated she would have to learn very swiftly in the coming days. Analysis of character was not one of those skills. Ashielle had met men like this before.

He had soft, gentle features and a round, chubby face. His hair was short, his nails clean. His clothes were tidy and neat, tasteful but not sumptuous. His jacket was short, offering no depths in which to conceal a weapon. He was heavier than was fashionable, although not so fat as to elicit comment. In short, every aspect of his being contributed to the general sense that the man presented no threat of any kind. Therefore, she concluded, he was an exceptionally dangerous man. Her father had taught her that only the most malevolent people cultivated such a well-manicured image of innocuousness. The stranger’s tinted, round-framed spectacles hid his eyes entirely behind mirrored lenses, which was perhaps the most damning trait of all. The eyes allowed a glimpse into the soul, and in Ashielle’s opinion, people who concealed them had something inside themselves they wanted to hide from those around them.

‘I don’t believe we’ve met before,’ she said.

‘We have not,’ the man replied. ‘I am Lostrovsky.’

Psycholinguistics had always been a passion of Ashielle’s. The idea that one could, through careful attention to one’s vocabulary and syntax, subconsciously influence actions or attitudes in a listener was an attractive one. There were days when she had her doubts as to the efficacy of its application, but she continued doing so anyway. At the very least, she reasoned, there was no harm in taking an extra moment to choose one’s words carefully.

‘What do you wish of me, Lostrovsky?’

The dangerous little man smiled. He had generous dimples that added to his harmless appearance, and he carefully presented his sad half-smile to show no teeth.

‘Nothing for myself, excellency. Rather, it is my mistress who would speak with you.’

Ashielle was intrigued, but it wouldn’t do to let Lostrovsky know that.

‘Who might your mistress be? One could consider it a grave insult that she doesn’t deign to make her requests of me in person.’

Lostrovsky shook his cropped little head. ‘My mistress is acutely aware of your excellency’s social station,’ he said. ‘She knows it would be improper for a supplicant of noble bearing to approach you on such an occasion. Hence her decision to employ a man of no particular house allegiance for this task.’ He made a humble gesture at his attire, as if to demonstrate his own inoffensiveness, in case she had missed it. ‘However, she did not want to pass up the opportunity to speak with you in this rather informal setting. Were you to seek her out here, in the Korgana, it would merely be a chance meeting at an event you were both attending already. Should she be required to seek you out, her attendance to the palace at Darcarden would certainly attract more notice than the two of you would wish.’

Ashielle had a sinking feeling she knew who Lostrovsky was referring to. Minor nobles made appointments to visit the governor at Darcarden nearly every day. There was only one ruling family whose presence at the governor’s palace would be worthy of comment.

‘Esilia Vaneisen calls a meeting? Now?’ Ashielle fixed Lostrovsky with an icy glare. Lord Ruprekt had mastered the bloodless stare, a skill Ashielle had tried to emulate. She had utilised the technique before, but this was her first time doing so with the authority of the title of governor behind her. She had never been sure if it was the threat that the title carried, or rather the confidence that it imparted, but Ruprekt had been able to chill a supplicant in their tracks with his gaze.

Lostrovsky was no street thug, but he seemed unnerved.

‘No, of course not,’ he said. ‘My mistress would never think of compelling your excellency’s appearance in her presence,’ he said, his tone making it clear that he was implying quite the opposite. Even without his practised delivery, she would have known the truth: Vicereine Esilia Vaneisen, coadjutor to the planetary governor, meant for Ashielle to attend her then and there. Better to clear up any misunderstandings about their relationship immediately, before the city could go back to the mundane routines of daily life.

‘So the impropriety might be mine alone?’ Ashielle said. She crossed her arms, fixing the unctuous Lostrovsky with a wicked sneer. ‘I think not. If Esilia wishes to speak with me, then she’ll simply have to take the hit to her pride.’ She made a flicking gesture with one hand. ‘You, on the other hand, should go before I have time to contemplate the audacity it would take not only to attempt to coerce a planetary governor, but to do so on holy ground.’

Lostrovsky bowed, a sheen of sweat visible on his forehead. Good. She hated the notion of ruling like a tyrant, but she was no one’s puppet.

The other dignitaries were less audacious. Most of them repeated the same sort of platitudes they had already given her. A few kept their words perfunctory and light, as though burying her father was just an unpleasant formality, and now they could all move on as if he had never existed. She reasoned that to many of them, he was merely a distant figure, with no more a personal relationship to them than the sun above. So long as the dawn came, she couldn’t blame them for not being as broken as they might have been. Their honesty was refreshing, if anything.

More than a few had gathered around Hanrik. She supposed she couldn’t blame them for that, either. The youngest of the Matkosen children was something of a curiosity, having been sent away at a very early age. For many of those in attendance, it was the first time they’d seen the returned son.

By the time she had made her rounds of the minor nobles vying for her attention, he had been surrounded by a small knot of mourners. Ashielle noted with no small amount of amusement that several of those eager to hear more about the estranged Matkosen child were eligible young women of the minor noble houses. Hanrik’s disinterest was clear to her from a mile away, but several of the sons and daughters of the minor noble houses preened and posed and tittered at his small talk anyway.

‘Governor Ashielle,’ he said when she approached. Ashielle smiled at his stiffness and formality.

‘Arbitrator,’ she replied. ‘Will you be so good as to accompany me back to Darcarden?’

Hanrik paused for a moment, clearly weighing the discomfort of his various options. The two of them had never been close. She had few memories of him. He had always been a private child. With two heirs ahead of him and no valuable allies to be secured with his marriage, the truth was that Hanrik had been a potential danger rather than an asset to Ruprekt Matkosen. She had been too young to remember clearly, but Geordan had told her that their father had spent weeks arguing the issue with the Grevenate. The custom was an archaic one, he’d said, and no longer required or wanted in the governing family. An industrial crisis in the southern provinces had arisen, however, and protecting the lives of his citizens had necessitated every ounce of political capital he could spare. As always, when forced to choose between family and duty, their father had chosen his obligations to his people. Ruprekt had needed to pull many strings to get his youngest son accepted to the schola progenium on Sorinoux, but he had done what was required of him.

‘I would be happy to escort you to the palace,’ he said carefully. His words were chosen cautiously so as to neither exclude nor include the possibility of staying in the palace itself. Ashielle smiled. Perhaps they had more in common than she had previously thought.

‘My lady?’

Ashielle was surprised when she turned to find Esilia Vaneisen behind her.

Many of the wealthy elite of the Imperium used their influence and fortunes to stave off the effects of ageing, often reversing their physical appearance to a visage of youth. Not so with the matriarch of the Vaneisen family. Vicereine Esilia Vaneisen, coadjutor of Ceocan, chose instead to wear her age proudly, as both challenge and threat.

Look here, her steel-grey hair boasted, I have borne the weight of years; I have seen decades of sorrow and treachery. Every furrow on her perpetually scowling face was a campaign ribbon declaring her participation in some deep-seated feud with another dignitary, now humbled and long forgotten. Like many institutions of the Imperium, she might be weathered and weakened by the passage of time, but her resilience had not failed yet, and was not likely to do so in the near future.

‘Will you excuse us?’ Ashielle asked the gathered courtiers. She gave her brother the dignity of a personal dismissal. ‘Hanrik, would you be good enough to wait in the carriage? I’ll be there shortly.’ Her brother frowned, but strode off towards her carriage dutifully, picking his way through the tombstones and mausoleums. The other courtiers, egos stinging, retreated to their various families, leaving the governor and coadjutor alone in the garden.

The Augusta Korgana, like most cemeteries on Ceocan, was laid out not in the neat ranks and rows that predominated on worlds of the Imperium. Instead, the raised headstones and monuments were arrayed along twisting paths that intersected and branched in a maze of loops and spirals. The mourning gardens situated amid the curving paths were oases of respite, where nobles could rest and reflect amid small patches of grave blossoms.

Ashielle seated herself on one of the stone benches, decorated with a bas relief of Saint Symion smiting the unbelievers at Loresk. She folded her hands in her lap and cocked her head. In private audiences between nobles, etiquette demanded that social inferiors spoke first. Among peers, however, the honour of speaking second was passed to the eldest participant. Esilia regarded her, silently. Ashielle recognised the trick for what it was. If she gave into the instincts of a young noblewoman to defer to the matriarch, Esilia would begin both the conversation and their entire professional relationship in a position of authority.

After a moment, the elder woman realised Ashielle had no intention of speaking first.

‘Poor thing,’ Esilia said, feigning a matronly concern. ‘Here I am, waiting for you to speak first. How silly of me to stand on formalities in your time of grief.’

‘Not at all,’ Ashielle said, placing a forgiving hand on Esilia’s arm. ‘I’m grateful for your slip. Why, if I had similarly forgotten myself it might have looked inappropriate. We are, after all, no longer peers.’

Esilia Vaneisen frowned. The elderly matriarch had clearly expected this conversation to go differently. In each of their previous encounters, Ashielle had given way to Esilia, accepting her barbs and her slanders with downcast eyes and accepting nods. In every previous meeting, however, she had been the second heir, not the lord governor.

‘My apologies, my lady.’ Esilia switched tone. ‘The working relationship I developed with your father was so close that there were times when we regarded one another as peers. I forget that we have not yet developed so close a bond. Perhaps when you have been governor for more than a short time, we can build such a rapport.’ Her words were kind but Ashielle knew what she meant: a reminder that she had been a veteran at planetary politics before Ashielle had even been born.

‘I hope that we can build a relationship that close between ourselves,’ Ashielle said, answering Esilia’s lie with one of her own. ‘In time.’ She was cognisant of the eyes upon them. The gravestones, decorated with the winding knotwork and images of Imperial saints, were rarely tall enough to obscure sight, and the lesser nobles that ambled their way through the winding paths of the Augusta Korgana were taking their time, casting surreptitious looks back to the mourning garden. The words between her and Esilia might be private, but everyone was making sure to take note of their conversation, all witnesses eagerly doing their best to discern some clue as to the context of the meeting.

‘Forgive me, my lady.’ Esilia bowed her head as if committing some egregious crime. More egregious than the ones Ashielle knew about, at any rate. ‘I had hoped to broach a sensitive topic. I know it is a rather unfortunate time, but we find ourselves in a rather unfortunate situation.’

Ashielle cocked her head again. ‘Oh?’

‘As my lady may or may not be aware,’ she said, ‘when your own father ascended to the throne, he was already wed, with your brother Geordan already on the way.’ She was on more comfortable ground now, educating a younger noble on events that she had personally witnessed, as if Ashielle couldn’t possibly have heard about the circumstances of her father’s coronation. ‘In fact, the governor’s throne hasn’t been without an heir for over three millennia.’

‘Two,’ corrected Ashielle. ‘You’re referring to the Reformation, when a plague epidemic killed half the nobility. You’re forgetting about the second Great Collapse. Lord Governor Windover died without producing an heir, despite his four successive wives.’ Esilia cleared her throat, but Ashielle continued without pause. ‘Of course, the Matkosens were the coadjutor family at the time, and Sadion Matkosen had a number of heirs. Governorship was transferred to the new ruling family without incident, and the Grevenate elected a new coadjutor from among their number.’ Ashielle’s face brightened. ‘The Netsullens, if I recall correctly, although I believe they married into a wealthier, if genetically stunted, family and changed their name. To Vaneisen, I believe.’

Esilia sat, her face as impassive as the stone angels carved into the mausoleums around them. ‘I believe that’s correct,’ she said. ‘Broadly, at any rate.’

‘The Netsullens had a bit of wealth, and were owed quite a few favours,’ Ashielle said, ‘but they lacked somewhat in prestige, didn’t they? Something about the business they were in?’

Esilia cleared her throat. ‘Quite possibly,’ she said. ‘Waste management has long been considered a disreputable profession, despite the immense value it has, especially on an agri world. For their part, the Vaneisen family had reached an… unfortunate state of being unable to continue their practice of marrying within their own line,’ Esilia said. ‘Too few cousins to keep going, I suppose. Fortunately, in this instance, as is often the case, uniting two noble houses provided the remedy to both their ills.’ She folded her hands in her own lap, and gave Ashielle a serene smile.

Ashielle smiled sweetly. This was the battlefield her father had trained her for. She’d never faced an opponent with as much clout as the Lady Vaneisen before, but she had learned from the best. She paused for a moment, staring at the pale white weeping lilies arrayed around a stone aquila in the centre of the reflecting garden.

‘Why, Esilia, do you imagine the example from your family’s history has some sort of bearing on current events?’ No matter how reasonable the request, she couldn’t afford to let Esilia Vaneisen deal with her on a level playing field. She had to keep the old woman off-balance, treated like a pauper begging for alms.

Lady Vaneisen looked around as if considering whether or not to continue. She had to realise what Lady Matkosen was doing, of course. By refusing to acknowledge what Esilia was implying, she forced the elder noble to spell her request out in ever more explicit, and ever more demeaning, terms.

‘Your father was ever a proponent of stability,’ Lady Vaneisen said finally, ‘and the current situation is anything but stable. As coadjutor, it would be my recommendation that you find a spouse and produce an heir as swiftly as possible.’ Ashielle had to hand it to her rival: framing her power play as part of her duties as coadjutor was a wise manoeuvre, which gave her requests the veneer of respectability.

Ashielle gave a small nod. ‘Of course,’ she said, ‘when matters of state permit, that would be one of my first priorities.’ Esilia looked pained, but Ashielle went on. ‘You understand, given the suspicious nature of the accident that claimed both my father and elder brother, the need to reevaluate our security measures before we allow an outside influence into Darcarden.’

The Korgana was beginning to empty. There was no reason to remain in the icy drizzle any longer, and most of the Grevenate families had begun to retreat to their own homes, to pursue their own petty interests.

‘We could, of course, offer our assistance in that regard,’ said Esilia.

‘Oh?’

‘Of course,’ the matriarch said. ‘We have a number of young men who would be suitable matches, I should think.’ She waved a hand and smiled as if they were old friends. ‘Such closeness between the regent and coadjutor families would be good for the political landscape, I believe. Unity is our best course in the wake of such tragedy, don’t you think?’

‘Oh, Esilia,’ said Ashielle, ‘not at all.’

The old woman looked as if she’d been slapped. ‘No?’

Ashielle shook her head and stood. The gesture wasn’t dramatic, but it was enough for anyone looking at their conversation to gather that she had rejected whatever offer had been put before her.

‘I admit to a certain degree of inexperience,’ Ashielle said, ‘although not as much ignorance as you apparently credit me with. It would take a great deal of ignorance, after all, for a house such as mine, with as solidified a reputation for honouring their obligations to the planetary populace, to marry into one such as yours.’

Esilia kept smiling, although her eyes were wide and furious.

‘Providing protection to the flesh peddlers, narcotics traffickers and extortionists of Kostoveim would be bad enough. But the rumours? The strife societies? The famed Black Mask balls your family hosts? And what happens to the… entertainment afterwards? My dear Esilia, even if only a fraction of the stories are true, the perversion would simply be too much to bear.’

She unfolded her umbrella and strode away, leaving Esilia Vaneisen fuming quietly on the stone bench in the graveyard.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...