- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

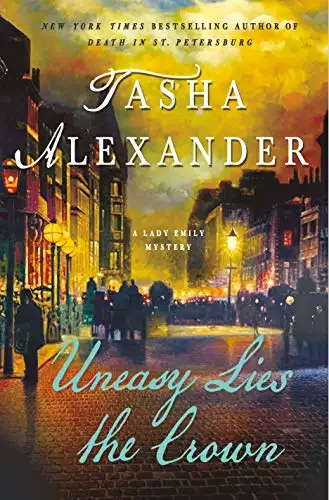

In Uneasy Lies the Crown, the thrilling new mystery in Tasha Alexander's bestselling series, Lady Emily and her husband Colin must stop a serial killer whose sights may be set on the new king, Edward VII.

On her deathbed, Queen Victoria asks to speak privately with trusted agent of the Crown, Colin Hargreaves, and slips him a letter with one last command: Une sanz pluis. Sapere aude. "One and no more. Dare to know."

The year is 1901 and the death of Britain's longest-reigning monarch has sent the entire British Empire into mourning. But for Lady Emily and her dashing husband, Colin, the grieving is cut short as another death takes center stage. A body has been found in the Tower of London, posed to look like the murdered medieval king Henry VI. When a second dead man turns up in London's exclusive Berkeley Square, his mutilated remains staged to evoke the violent demise of Edward II, it becomes evident that the mastermind behind the crimes plans to strike again.

The race to find the killer takes Emily deep into the capital's underbelly, teeming with secret gangs, street children, and sleazy brothels-but the clues aren't adding up. Even more puzzling are the anonymous letters Colin has been receiving since Victoria's death, seeming to threaten her successor, Edward VII. With the killer leaving a trail of dead kings in his wake, will Edward be the next victim?

Release date: October 30, 2018

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Uneasy Lies the Crown

Tasha Alexander

Osborne House, Isle of Wight

The stench of death already clung to the salmon pink walls of Queen Victoria’s bedroom; it assaulted Colin Hargreaves the moment the footman opened the massive oak doors. Not death, he corrected himself, but dying, when musty decay had not quite given way to the cloying foul rot soon to come. He hesitated for a moment, not because of shock at seeing how small Her Majesty looked, as if a child had been placed in a formidable marriage bed, but because the odor sent him reeling as he remembered the first time he had smelled it, on a snowy afternoon at Anglemore Park. He was home for Christmas during his first year at Eton and had found his grandfather in the library. The old man, sitting in his favorite high-backed leather chair, read aloud from Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur until Nanny came to fetch him for supper. Colin had noticed the odd scent, but didn’t think anything of it until the next morning, when his father delivered the news that Grandfather had died overnight. He smelled it again when he was summoned home from Cambridge to his father’s sickbed. Then, too, for just an instant, he had felt like a schoolboy stunned by his first loss.

He shook off the feeling and approached the queen. Her enormous bed faced windows with a sweeping view of the countryside, a stark contrast to the paintings on the walls, nearly all of which depicted religious subjects. She was sitting, propped up by pillows, beneath a favorite portrait of her long-dead husband and a memorial wreath. Her eyes, dull, stared ahead, and he wondered if she knew he had entered the room.

“Your Majesty,” he said, his voice low as he bowed. “You asked to see me.”

She managed a half smile and nodded. “There are things I would like to settle, but I fear I shall not be given enough time to accomplish them all.” She coughed, cleared her throat, and motioned for him to give her the glass of water sitting on her bedside table. He held it to her lips as she drank, swallowing with difficulty. “One never knows, does one, what shall happen in the end? My dear Albert…”

Sir James Reid, her physician, standing on the other side of the canopied bed, met Colin’s eyes and shook his head, exhaustion and worry writ on his face.

“How can I assist, ma’am?” Colin asked.

“So much, so much to be done,” she said. “And the dogs … I do not see them. Are they here?”

“No, ma’am, they are not,” Sir James said. “Shall I have them brought to you?”

“Why are you here?” Her voice, though weak, grated with a tone of scathing disapproval. “We are not in need of your services. I must speak to Mr. Hargreaves privately. Disperse.” Sir James shot Colin a pointed look and left the room. When she heard the doors close, the queen pushed herself up on the mountain of pillows. “It is too much to be borne. The loss of Lady Churchill…” Her voice faded and she stared out the windows. A lady of the bedchamber for nearly fifty years, Lady Jane had long been one of the queen’s closest confidantes. Keenly aware that learning of her death, on Christmas Day less than a month ago, would come as a tragic blow to the already ailing monarch, Sir James had done his best to deliver the news gradually, trying to shield Her Majesty from suffering the shock all at once.

“It was devastating to lose her,” Colin said. “I know she was a dear friend—”

“That is of no significance now,” she said. “No death matters but that of Albert.” Her eyes clouded. She raised a hand, its skin yellowing and dry. “Nothing has been right since then, and now I am left to summon you and demand a service that only you can provide.”

“Of course, ma’am, whatever you need.” He shifted on his feet, wishing he had been able to speak to the doctor before seeing the queen so that he might better understand her condition.

“Take this and do as it says.” She pulled an envelope from under her pillow and handed it to him. “All will be clear in time. We need you for this. There can be no one else. I had five others during my reign, but he will need no one save you. He’s never been so strong as I.” She dropped back onto the pillows, the effort of holding up her head too much. “I shall not see you again, Mr. Hargreaves, but I have always valued your service above all others and thank you for your devotion to the Crown.” She lifted her hand again, holding it up as if to be kissed, but lowered it almost at once. “Tell no one of this meeting, of what we have discussed. Discretion is of the upmost importance, as you shall know when you read my note. Albert would concur, and will, I am sure. Have you seen him of late? He is such a fine gentleman.”

“The finest, ma’am,” Colin said, seeing no reason to acknowledge her confusion.

“That is all,” she said, her voice so low he could hardly make out her words. “Disperse, Mr. Hargreaves, with our thanks.”

He did as ordered and found Sir James waiting in the corridor outside. “She has been struggling since December and is growing more muddled by the day,” the doctor said. “I fear she does not have long. No one but the family and the household here knows of her illness yet. I trust I can rely on you to keep what you have seen to yourself?”

“Of course.”

“Soon enough we shall have to notify the press,” he continued, “but I should like to delay that while I can.”

“Understood,” Colin said. “If I can be of any further service, you need only ask.” He took his leave from the physician and retired to an empty sitting room, where he opened the queen’s envelope, ready to follow her instructions, but the words scrawled on heavy linen paper inside did nothing to illuminate her desires:

Une sanz pluis.

Sapere aude.

One and no more.

Dare to know.

1901

1

The death of Queen Victoria stunned the nation, myself included, although I cannot claim to have suffered a personal blow from the loss. My mother, who had served Her Majesty as a lady-in-waiting, mourned and keened (more than strictly necessary, I suspect, but she wanted no one in doubt of her close relationship with the monarch), while I sat shocked as my husband, Colin Hargreaves, delivered the news. He had seen her at Osborne House only five days before her demise, and although I had surmised her to be ill, it had never occurred to me that she might be near death. Colin, always the soul of discretion, had revealed nothing about the meeting. The truth is, because she had been queen for so long, was such a formidable personality, and had survived eight assassination attempts, part of me believed she would never quit the mortal world.

But she did, as we all must, and I sat with my parents on a special train from London to Windsor, en route to the funeral service. Colin, who would be walking in the procession to St. George’s Chapel, was on another train altogether. My mother, her eyes red behind her crêpe veil, would accept no words of consolation, so my father, long immune to the glares of his spouse, dedicated himself to rereading Mr. Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities until we were ushered off the train into flower-filled waiting rooms at Windsor Station to await the carriages that would carry us to the castle. The crush of people in the small town was like nothing I had ever seen. Boys climbed fences and lampposts to get a glimpse of the gun carriage pulling the royal coffin, draped in a white pall, with the Imperial Crown, Orb, Sceptre, and the Collar of the Order of the Garter on top of it. Crowds, ominously silent, lined the streets, every person dressed in black, all the men wearing wide crêpe armbands. The only sounds were those of the horses’ hooves clattering and their harnesses jingling.

We reached the grounds of the castle, and hence the chapel, long before the procession, which wound slowly through town. Inside, we mourners sat, not speaking, all but afraid to move and disturb the sanctity of the place. For a while, at least. There was so little heat that before long we were all too focused on keeping our teeth from chattering to think about anything else. By the time Colin slipped into the seat next to me, I was half-frozen. It seemed that an eternity passed before the pallbearers carried the coffin to the choir and the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Winchester presided over a thankfully short service. After the final notes of Beethoven’s Funeral March rang from the organ, we joined no fewer than six hundred other guests for lunch in St. George’s Hall. The somber occasion had left everyone preternaturally quiet, but we were not dining with the royal family or those closest to the queen, and by the time the second course arrived, conversation had returned to normal. Only a handful of people in the room could remember a monarch other than Queen Victoria; all of us would have trouble getting used to King Edward VII.

I had just leaned over to my husband to ask him what he thought of the profligate Bertie now having such a grand title, when a member of the Household Cavalry approached, bent down, and whispered something to him. Colin’s face grew serious, his dark eyes flashed.

“There’s been a murder in the Tower,” he said, folding his napkin neatly and placing it next to his plate. “I must return to London at once.”

* * *

A murder in the Tower of London! I must confess the idea sent a thrilling little shiver down my spine. The Tower loomed large in the imaginations of every child growing up in England, and as the young (my own three boys included) are inexplicably drawn to hideous and ghastly tales of ghosts and violence, there was no place that could better satisfy their cravings for such things. I thought of the poor little princes, sons of Edward IV, who went into the Tower never to return. Had their uncle Richard III murdered them? Personally, I suspect not, but that is a topic for another day. When we took our boys to the Tower for the first time, Henry insisted that he could hear the ghost of Margaret de la Pole shrieking as we approached the site of the scaffold where she had been executed. And who has not heard it said that a hooded figure, missing her head, is often seen wandering in the chapel where Anne Boleyn is buried? I could not help but succumb to a touch of juvenile titillation at the thought of a new murder at the Tower. Would this incident enter into the lexicon of legend?

My husband and I are no strangers to violent crime. He, as an agent of the Crown (and a particular favorite of the late queen’s), was called upon to serve in countless investigations that, as he often said, required more than a modicum of discretion. I had proven myself a capable detective on numerous occasions, and whenever possible, we worked together. When he was acting in his official capacity, it was more difficult for me to contribute, but I am never deterred by an arduous path. And an arduous path was precisely what I faced that afternoon.

To start, Colin murmured that there was no need for me to accompany him to London, but as I knew he would never be so gauche as to argue at a funeral luncheon, I insisted on boarding the train with him. A lively discussion ensued until we reached Paddington Station, by which point he admitted defeat and abandoned all attempts to dissuade me from going to the Tower. I cannot credit my powers of persuasion for his decision; more likely it resulted from exhaustion. He hadn’t slept more than ten hours total since the queen’s death and was nodding off for much of our journey, becoming fully alert only as we alighted at the medieval fortress.

Like all the flags in the country, those at the Tower flew at half-mast. We approached the sturdy outer wall and met a yeoman warder who ushered us in through Lion Gate, devoid of its usual swarms of tourists as the site was closed due to the queen’s funeral. Once inside, he led us past the Bell Tower, with its oddly placed small white turret at the top, containing, appropriately, a bell. My attention then turned to the stark face of Traitors’ Gate and I felt the skin on my neck prickle, the sensation disappearing only as we approached Wakefield Tower. Built by Henry III in the thirteenth century, its thick stone walls—the second tallest in the fortress—were designed to safely house the king and his family. No longer a royal residence, it now held the Crown Jewels. Had the murderer’s victim been slain in an attempt to steal them?

Yes, once again, the romance of the Tower was getting the best of me. But who could resist? The timing was almost perfect for such an audacious heist; the royal funeral had distracted all of Britain. Yet an ambitious thief would be unwilling to miss the prizes of the collection, particularly the Imperial Crown, currently sitting atop the queen’s coffin. I was about to voice this to Colin when I realized we were going not to the room that held the jewels, but instead to the modest chantry chapel originally intended as a private place of worship for medieval kings.

There, on the ancient brown tiles covering the floor, knelt a man dressed in black tights, a black tunic with white trim, and a matching hat. His hands were folded as if in prayer, his legs neatly together behind him, but his position was at odds with the expression on his face. His gray eyes were open wide and his mouth gaped in what looked like a silent, terror-filled scream.

He was dead, of that there could be no question. A sword stuck in his chest, penetrating all the way through his back, but no blood pooled around his body. That he remained upright rather than sprawled on the ground seemed inconceivable until my husband revealed thin wooden posts constructed to form a sort of frame and hidden by the tunic and tights. Fishing line held his arms and hands in place.

Colin crouched to examine the sword. “It’s in the style of late fifteenth century. The sort we’re led to believe would have been used to kill Henry VI—”

“Who was stabbed to death in this very room,” I finished for him. “And our victim is dressed in an outfit nearly identical to that the king is depicted wearing in the painting at the National Portrait Gallery.”

“Yes.” He rose and paced the perimeter of the chapel. “I recall the hat in particular.”

“Do we have any idea who he is?”

“Not as yet,” Colin said. “The police are checking missing person reports.”

I nodded. How awful that his family had no idea that their loved one was kneeling here, dead. “There’s too little blood for the crime to have been committed here,” I said.

“And we’ve found none elsewhere,” the yeoman warder said. “Madam, I must warn you that when Scotland Yard arrive they’ll insist you leave. I shouldn’t have allowed you to enter in the first place. The inspector is rather touchy.”

“I am all too aware of the limitations of Scotland Yard,” I said, “but thank you for the warning.” I smiled at him. One never knows when an individual may prove helpful in an investigation, particularly in those from which one is—theoretically—banned from participating. Colin glanced at me, raised an eyebrow, and then turned back to the guard, inquiring as to whether he or his colleagues had noticed anything unusual during the course of the day. The yeoman warder admitted that they had all been affected by the queen’s death, but was adamant that no one had been derelict in his duties. The warden had increased surveillance of Wakefield Tower as a precaution against anyone viewing the occasion of the funeral as an opportunity to make off with the Crown Jewels.

We combed every inch of the structure but unearthed nothing we could consider a clue. I was about to suggest interviewing the wives and children of the guards who lived in the Tower—they might have noticed something out of the ordinary their husbands had not considered significant, like an unfamiliar tradesman delivering goods—but was stopped by the arrival of a humorless man from Scotland Yard. He introduced himself as Inspector Gale and ordered me from the room with little ceremony, explaining in cursory fashion that the interference of a lady would not be welcomed by His Majesty.

Rather than engage in a fruitless argument, I retreated with uncharacteristic silence; I saw no sense in antagonizing Inspector Gale. At least not yet. Outside of the fortress, I marched to the banks of the Thames. Obviously, the crime had not taken place in the chapel, and I suspected the murderer had brought his victim’s body from outside the Tower. Unless he was one of the guards—a possibility I could not eliminate—but as I could not investigate inside, I was forced to explore other options. I followed the river until I found a man, rather scruffy, with a rowboat and offered him a not quite princely sum to take me for a little excursion on the river. He hesitated at first when I told him my destination, but, as I had hoped, the money was too good to ignore.

The boat bobbed as I stepped off the dingy pier to which he had tied it, but I managed to steady myself and avoid falling into the filthy-looking water. Our journey was a short one, to the most notorious of all entrances to the Tower, Traitors’ Gate, through which had passed countless prisoners on their way to execution at Tower Green. I thought of Thomas More and Anne Boleyn coming this way, beneath London Bridge with its severed heads on pikes serving as reminders of what lay in store for them. I considered the tragic story of Lady Jane Grey, the sixteen-year-old queen, whose reign lasted a mere nine days, and whose execution led many to consider her a martyr.

But once again, the Tower was leading me astray. I could not allow myself to become mired in history, however tempting it might be. Today another man had died, and I suspected that he, too, had entered the Tower through Traitors’ Gate. The boat churned in the water, fighting the rising tide. I asked the man to row closer, until I realized my mistake. Although the words “Entry to the Traitors’ Gate” were painted clearly above the arch marking the space, the gate itself had been bricked up, probably in the middle of the previous century during the construction of the Thames Embankment. It was a blow. I had never noticed the alteration during previous visits to the Tower, where Beefeater tour guides always pointed out the notorious place. From the inside, it was not so easy to tell there was no access to the river.

A voice cut through the cold air and I looked up to see Inspector Gale standing on the rampart above. “Lady Emily, I must insist that you stop meddling. This investigation will be treated with the utmost sensitivity and I shall not tolerate any interference. Return home at once or the king will have words with your husband.”

Frowning, I ignored him, continuing my study of the brickwork near the top of the arch. Traitors’ Gate might no longer be an easy way into the Tower, but the fortress held many secrets, not to mention many entrances. Some might now be sealed, but were there any, long forgotten, that might provide a vicious criminal with a path into this place that once protected kings?

1415

2

Cecily Bristow—or Hargrave, as she now was—could not recall a single detail of her wedding. The ceremony had passed in a blur of incense and candles. Yet she could not deny it had occurred, for here she was, sitting at the high table next to her husband, William, a splendid feast before them. The gold and silver plate on the cup board gleamed, and Lord Burgeys’s magnificent saltcellar, made from French porcelain and depicting scenes from the life of Hercules, was barely five feet from her. She and William spoke very little during the meal, but he took her hand three times and squeezed it, which she found reassuring.

“You play the part of anxious bride well,” Adeline, Lord Burgeys’s granddaughter said, leaning close as she spoke. “I wonder if your groom believes the act.”

“You ought not speak in such a manner,” Cecily said. “He won’t know you’re teasing.”

“He knows you’re as good and as boring as you seem.” Adeline scowled. “Yet he agreed to the marriage nonetheless. I’m only trying to make things more interesting for you.”

Cecily had no need for interesting. Was she anxious? Yes, but not because of what lay in store for her that night. Adeline, whose own marriage had taken place only six months ago, had done her best to instill terror in her, but Cecily knew better than to listen to her harsh words. She did not fear William; she feared France. France, where he would be off to in less than a fortnight, to fight with the king to secure his rightful place on the throne of that country. Henry V, King of the Britons, was brave and good and would lead his men well. Yet battle was full of uncertainty, and although William had won tournament after tournament, this would be his first time at war. He might not return.

Could she bear the loss with equanimity? Perhaps. He wrote her pretty poems and sang to her, but she had not spent enough time with him to come to rely upon his presence. And as his wife, she ought not expect to. A knight was gone from home more often than not, and her role would be to manage their estate. Except that for now, there was no estate to manage.

William served under the king’s youngest brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and lived on the duke’s estate rather than in the manor house he had inherited upon his father’s death. That house, William had given to his own brother, who had married before him. Cecily was to stay with Adeline while her husband was in France, and upon William’s return, the couple would set up housekeeping together. Everyone agreed it was an excellent plan, particularly Lord Burgeys, who hoped Cecily would prove a tempering influence on his granddaughter, assuming, as did the rest of his household, that the girls were great friends and would be delighted to continue living together.

Except that he was wrong. Cecily and Adeline had never been friends. Tenuous rivals for Lord Burgeys’s attention, perhaps, when they were children, but from the moment they reached adulthood, the differences between them could not have grown more pronounced.

On the surface, one could be excused for thinking they had more in common than they did, but only because they were unaware of Cecily’s true feelings about her mother, whom, at the age of two years, Lord Burgeys had found wandering alone on the road more than thirty miles from his estate. He brought her to the nearest village, thinking to reunite her with her family, but found it shuttered and silent. The child seemed to recognize the place, and rushed into a house near the green. Burgeys followed, pulling her out the instant he saw the bodies inside. The most terrible of the plagues that devastated England had ended the decade before, but the disease still recurred from time to time, and now it had wreaked havoc on the girl’s home. She was the only one in the village who had not fallen victim to it.

Burgeys arranged for the burial of the dead and then had the buildings burned, lest any bit of the pestilence remained. But the girl who had so miraculously escaped death he adopted as his own, calling her Beatrix, explaining to her when she was old enough to understand that it came from the Latin word that meant traveler and that, later, Christians changed the spelling to reflect the word for blessed. Beatrix certainly was a blessed traveler.

As the solitary survivor of such a deadly outbreak of the plague, Beatrix was revered in the household. God had chosen her to live, and everyone viewed her with respectful awe. But the girl cared only for the spiritual side of life, eschewing all worldly pleasures and spending her free time in prayer. She blossomed under the direction of Lady Burgeys’s confessor and soon gained a reputation as a lady of impeccable holiness. Visitors came with sick children, asking her to heal them, and before long, she was known in three shires as someone who could perform miracles.

Beatrix might have lived out her days lost in contemplative prayer and meditation had Geoffrey Bristow never come to the estate. He fell in love with the quiet girl the moment he set eyes on her, and begged Lord Burgeys to let him marry her. Bristow’s fortune and position at court both recommended him, but neither mattered to Beatrix, who resisted her adopted father’s decision, pleading with him to allow her to enter the convent instead. She wanted nothing more than to dedicate her life to God. Lord Burgeys refused, and the wedding took place a few weeks later. By the end of the year, Beatrix, who took no pleasure in her new life, was heavy with child. She fasted and prayed and begged God to remove her from the chains that bound her to the earth. She wanted only to serve Him.

God must have listened, because Beatrix died the moment her daughter was born. Geoffrey shunned the child, whose thick hair and dark eyes were the image of her mother’s. He believed her to be cursed, and sent her back to Lord Burgeys, who named her Cecily and once more raised a child who was not his own. He insisted that Beatrix be buried on his estate, and her tomb soon became a place of pilgrimage, the desperate and unfortunate coming to pray to this woman who had miraculously escaped the plague.

Most pilgrims viewed Cecily with dubious caution. Was not she the result of a forced marriage, the daughter of a woman denied her true religious calling? But Cecily rejected the image of her mother as some sort of saint. To her, Beatrix was a flawed mortal who, not caring to bring up her child, died instead. Cecily hated being paraded in front of the pilgrims, hated tending to her mother’s tomb, and of all the instruction she received in Lord Burgeys’s household, she liked religious teaching the least. Not because she doubted the truth of her faith or because she was not devout, but because she always felt as if she were being judged as the instrument of her mother’s death. How did one atone for such a sin? She heard mass every day and prayed with a fervor unusual in one so young, leading everyone to consider her a fine example of piety. But that, Cecily knew, was only because they were ignorant of the depth of her sin. She had killed her mother.

Adeline, so far as everyone on the estate was concerned, was equally pious. Admittedly, she had mastered the art of appearing so at an early age, a skill she practiced because she found it exceedingly useful. She pretended to go to chapel when in fact she was sneaking to the barns to visit the horses. When she got older, she discovered she preferred the company of the stableboys to their charges. She was careful to avoid any truly licentious behavior, but relished what she considered her safe rebellion, all the while maintaining a reputation for sincere religious devotion.

The two girls did nearly everything together, but not by choice. Neither could tolerate the other’s true nature. Adeline loved toying with Cecily and did all she could to heap trouble upon her. Cecily, always feeling like a guest in the Burgeys household, never dared speak a word against Adeline. Cecily had rejoiced when Adeline married and left home, never suspecting that her own marriage would lead her to become a companion to the nemesis of her youth.

The scent of resin from the flickering torches hanging on the walls of Lord Burgeys’s great hall brought Cecily back to the present. She had hardly noticed the spectacular subtlety, a swan fashioned from sugar, when it was paraded in front of her. Mummers had started to perform now that the feast had ended, but Cecily did not give much attention to their act. She chewed on her lower lip and watched Adeline flirt with the gentleman seated next to her. A gentleman who was not her husband. She flashed Cecily a knowing look when William pulled his wife to her feet when the mummers had finished, but Cecily felt nothing but relief when he led her upstairs to the bridal chamber Lady Burgeys had organized for the couple. The guests cheered and her husband smiled at her.

“I knew the moment you gave me your favor that you would be my bride,” he said. They had met at a tournament—one of the many he had won—and he had paid court to her ever after, until Lord Burgeys agreed to their betrothal. Cecily fingered the gold and emerald ring on her hand, the one William had placed there to mark the occasion. “I know you will desire your ladies to help prepare you for bed, but I asked that we be left alone, just for a moment, as I have a gift for you. Come.”

He opened the door to their room. Once inside, he handed her a small package carefully wrapped in soft linen and tied with a red silk ribbon. She tugged at the bow and it fell away with ease, revealing a small wooden diptych. Covering the surface facing her was William’s coat of arms. On the other, his badge, a griffin rampant. She unfolded the hinge to reveal the interior panels, both gloriously painted. On the right, Mary held the infant Jesus, a chorus of angels surrounding them, their gilded halos glowing. On the left, a scene of the crucifixion.

“I had two made,” William said, “so that when we are apart we can both pray in front of the same images. And when I return, victorious, from France, I will commission a third, large enough for the chapel I will build for us.” She looked up at him as he spoke, her dark eyes scared. “Do not worry that I won’t come back. I shall never abandon you.” He took the diptych from her, laid it on a table, and raised his

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...