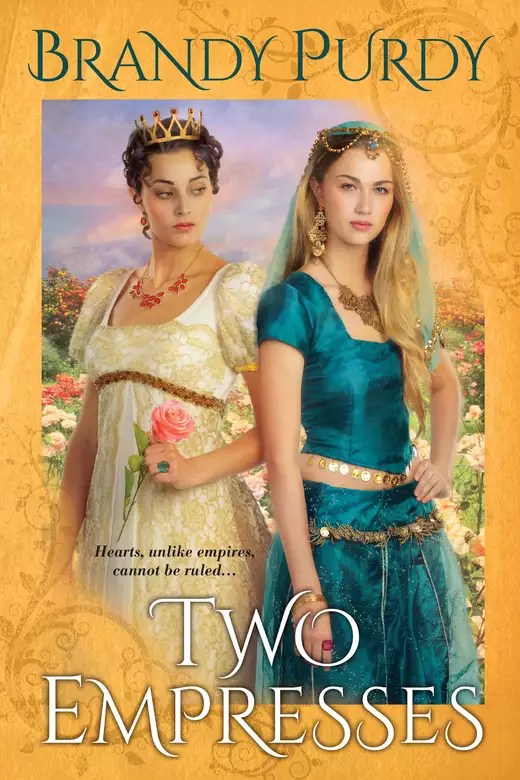

Two Empresses

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

1779, France. On the island paradise of Martinique, two beautiful, well-bred cousins have reached marriageable age. Sixteen-year-old Rose must sail to France to marry Alexandre, the dashing Vicomte de Beauharnais. Golden-haired Aimee will finish her education at a French convent in hopes of making a worthy match. Once in Paris, Rose’s illusions are shattered by her new husband, who casts her off when his mistress bears him a son. Yet revolution is tearing through the land, changing fortunes—and fates—in an instant, leaving Rose free to reinvent herself. Soon she is pursued by a young general, Napoleon Bonaparte, who prefers to call her by another name: Josephine. Presumed dead after her ship is attacked by pirates, Aimee survives and is taken to the Sultan of Turkey’s harem. Among hundreds at his beck and call, Aimee’s loveliness and intelligence make her a favorite not only of the Sultan, but of his gentle, reserved nephew. Like Josephine, the newly crowned Empress of France, Aimee will ascend to a position of unimagined power. But for both cousins, passion and ambition carry their own burden. From the war-torn streets of Paris to the bejeweled golden bars of a Turkish palace, Brandy Purdy weaves some of history’s most compelling figures into a vivid, captivating account of two remarkable women and their extraordinary destinies.

Release date: January 31, 2017

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 337

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Two Empresses

Brandy Purdy

I remember it vividly, my true birthday. At first, it seemed just like any other ordinary, ho-hum humid lazy day on the tropical, sugar-scented island of Martinique. I, Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de la Pagerie, was sitting, petulant and idle, on a window seat, my detested embroidery cast impatiently aside in a tangle of hopeless purple silk knots only a miracle could hope to untie. I was watching one of the sudden summer rains wash the veranda clean and pouting over an unfortunate raspberry jam stain marring the frothy white flounces of my new muslin gown with the double row of heart-shaped mother-of-pearl buttons marching down the bodice neat as soldiers. I had been careless at breakfast. My maid Rosette, always honest even in the face of my tears, said she didn’t think the stain would ever come out. Money was dear and I had ruined the new dress I had spent weeks weeping and wheedling Father for the very first time I had worn it.

There was a little green lizard climbing the window glass, so close I could see his tiny scales and beady black eyes and even count his long, spindly toes if I had a mind to. But I wasn’t interested in lizards; I was dreaming of Paris and handsome young men who thought I was the most beautiful and fascinating creature alive, men who would fight duels to be the one to lay the moon at my feet and hang the stars around my neck like a diamond necklace until one special man, a man above all other men, placed an empress’s crown on my head.

My mother, the still-beautiful Marie-Rose Claire Tascher de la Pagerie, was reclining wretchedly on the sofa, still wearing her ball gown, a shimmering mulberry silk festooned with black lace, now badly wilted and sodden with sweat beneath the armpits. She had been wearing it for three days. She had put it on to attend a party at a neighboring plantation.

Papa had insisted it was just the thing to chase her woes away. Besides, her presence would ensure he didn’t drink too much rum punch and make an ass of himself in front of our neighbors again. Papa was quick to remind her that the last time he had attended a ball without her he had picked up the punch bowl, guzzling like a parched fieldhand until he had drained it to the dregs, then run giddily about giggling and squeezing the breasts of every woman he could catch and comparing them to passion fruits and mangoes until the Governor had finally ordered the footmen to dunk Papa’s head in a basin of cold water and throw him out into the street. So Mama had reluctantly agreed, put on her best gown and a brave smile, and gone to the ball to ensure her husband’s good behavior.

When they returned, a slave had met them at the door with the sad news that my sister Catherine was much worse. She was delirious, burning with fever and coughing up blood. Mama had rushed straight upstairs to her and hadn’t left her side until this morning. Her high-piled pompadour of powdered hair was listing badly to the left and the silk roses and black lace garnishing it hung slovenly and slack, but Mama was too weary and worried to care. She hadn’t even thought to loosen her stays. She was lying back on the hard, torturously uncomfortable ancient green brocade sofa. Its badly frayed gold embroidery, as prickly as a porcupine’s needles, had been known to draw blood upon occasion, but today Mama didn’t seem to even feel it. She had a cold compress pressed tight over her tired, swollen eyes and a tear-soaked handkerchief and her black onyx rosary beads clutched tight in her other hand. She hadn’t even touched the cup of steaming black coffee her maid had brought her. She was just too tired to do anything.

My sweet, fun-loving ne’er-do-well papa, Joseph Gaspard Tascher de la Pagerie, was at his desk stealing fast, furtive sips of rum from his silver flask when he thought no one was looking and brooding over a stack of bills he had no hope of paying. He was longing, no doubt, to escape to Fort Royal and the comforting arms and bountiful bosoms and hips of his dusky-skinned mistresses, and the eternally springing hope that he might finally turn a lucky card or bet on the winning cock. Papa was a dreamer, not a doer, and one of the few plantation holders who had actually failed to make a profit from the sugar everyone called “white gold.” He loved to put on his white frock coat with the big gold buttons and his buff nankeen breeches and tan-topped butter-soft black leather riding boots and stride around the plantation like he was the supreme lord and master of all he surveyed, but everyone knew he didn’t know the first thing about running a plantation.

Thus were we arranged in the faded, threadbare grandeur of the best parlor at Trois-Ilets when Le Grande Jacques, our giant black footman, came in bearing the letter on a little silver tray.

I clamped a hand over my mouth, trying to hold back my laughter. Though Jacques had readily acquiesced to the stifling splendor of a gilt-buttoned and braid-trimmed burgundy velvet frock coat with tails that hung down to his knees and a matching waistcoat, a white shirt drowning in ruffles, ice-blue satin knee breeches so tight they might have been painted on, and even a white powdered wig, his big plank-flat feet just could not bear the prison of the sturdy black leather shoes with big shiny buckles and white cotton stockings. I think he would have gone barefoot even at Versailles in the presence of royalty. Jacques just could not abide shoes and stockings and always managed to “lose” every pair he was given. “’Dem is fo’ the white folks that has been bred to such things, but nobody never tried to put ’dem on me till I was already a man growed, an’ by den it was long too late fo’ my feet to take to ’dem,” he always said.

When Papa opened the letter and began to read I felt the world tremble beneath my feet. Here was my destiny come to meet me at last and I must let nothing stop me from rushing out to embrace it. I was ready to fly into the arms of the husband who would “cover the world with glory” and me with diamonds and ardent kisses. I felt my heart and heels grow wings. I knew that this letter was the first step along the path to the palace and crown Euphemia David had seen in my palm.

The letter was from Aunt Edmée. I had grown up relishing tales of Papa’s scandalous sister who had astonished everyone when one day, right after a most civilized and unremarkable breakfast, she just up and left her husband to go and live openly with her lover, our former governor the Marquis de Beauharnais, and his most amicable and obliging wife. The three of them had left Martinique and sailed back to Paris and set up house together and remained a happy trio until the Marquise’s death. Aunt Edmée was now seeking a bride, an island-born beauty, for her paramour’s son, Alexandre, the handsome young Vicomte de Beauharnais.

Since her own brother was blessed, or cursed to hear him tell it, with three daughters she had naturally thought of us first. They were even willing to overlook the fact that not a one of us had even a pittance for a dowry. Of course it was not an act of benevolence but calculated shrewdness on Aunt Edmée’s part. Hers was hardly an altruistic soul; her sharp eyes saw clearly the sense of keeping things in the family. Her lover was sixty-two and sickly, doughy fleshed and gouty by all accounts, and she was no spring chicken herself, hardly alluring enough to attract a new love when the old one was in his coffin. Aristocratic only in his titles and pretensions, not in his bank balances, the Marquis would leave her nothing but the debts they had acquired together. As a mistress rather than a wife, she could not rely upon his pension, that reliable though meager source of funds would die when he did, and her estranged husband was unlikely to welcome her back or offer to support her, all things considered. But if Alexandre and his bride were indebted to Edmée for bringing them together, gratitude would surely endure and they would provide her with a home and all the necessary comforts for the rest of her life.

“Let me go, Papa! Please! Let me go!” I cried, interrupting Papa midsentence and clinging to his arm, staring up at him with my most heartrending expression as I bounced excitedly on my toes. “Let me go to Paris and marry Alexandre!”

Paris was the dream of all dreams. By rights, my sisters and I should have been sent there to be educated long ago, but years of bad harvests, the devastation wreaked by hurricanes, and Papa’s gambling debts, combined with a blockade by the British that had prevented us from exporting our sugar, had made this impossible. Thus we had all had to make do with what little the nuns at the convent in Fort Royal could teach us, though I for one found dancing with the soldiers at the Governor’s balls and sneaking out into the garden or to walk on moonlit beaches, sometimes even daring to strip for a midnight swim with them, much more educational than anything the nuns ever taught me. The Sisters were for the most part sweet, but clearly they knew nothing of life and even less about love.

“Rose, I have not even finished reading your aunt’s letter. . . .” Papa shook me off, and from the sofa, over the rustle of wilting mulberry silk, Mama sighed, “Have patience, Rose. . . .” Sometimes it seemed that was the only thing she ever said to me. “Have patience, Rose; have patience. . . .”

Well, I was tired of having patience or pretending that I did! I didn’t want to have patience! As a virtue I thought it was vastly overrated and I didn’t give a fig what the nuns or Mama thought about it! I wanted to dance, and have fun, and live and love while I was young enough to enjoy it all. How could they expect me to act like an old woman and bide my time and sit by the fire embroidering flowers or placid platitudes when I was so full of vitality and passion? I was bursting at the seams; why couldn’t they see that?

As Papa continued to read, my heart plummeted. Alexandre wanted Catherine. Of course he did; she was the youngest and prettiest of the three Tascher de la Pagerie sisters. I was the eldest and the least likely a man so exacting as Alexandre de Beauharnais would choose to marry.

My teeth were already rotting, full of cavities and stained an ugly yellow-brown. My wet nurse had weaned me from her breast with sugared milk and I had been in love with sugar ever since. I ate it raw and put it in everything I ate or drank; I simply could not go a day without it. Although I spent hours at my mirror perfecting a charming closemouthed smile, to lure and pleasure a man I must open my mouth sometime, and I couldn’t hide behind my fan all the time. And things like that really mattered to a man like Alexandre.

“But Catherine can’t go; she’s dying!” I blurted without stopping first to think. I clamped a hand over my mouth, too late to stop the cruel, if honest, words from flying out, and glanced worriedly over at Mama. She just could not admit, poor dear, that all hope was gone and Catherine would die long before she ever had a chance to live. But Mama had already turned her face away and was fingering her rosary, still praying for a miracle that we all knew would never come; Euphemia David said so.

“I’ll just go and check on Catherine,” Mama murmured as she hurried out before we could see the first tear fall.

Catherine had the wasting sickness. Her golden hair was as dry and brittle as straw and her skin yellow as bananas and there was a persistent rattling in her chest like peas inside a gourd. The nuns had sent her home to die. The doctors could do nothing for her except bleed her, which only made her weaker, and she could rarely keep down the bread and milk and mushed bananas Mama diligently spooned into her mouth. No tonics, prayers, voodoo charms, or magic spells could save Catherine.

Though Mama was a staunch Catholic and unwilling to risk her daughter’s soul, or her own, by consorting with witches, Papa had sent for the voodoo queen in secret one morning while Mama was at Mass. He had tremendous faith in her and knew if anyone could save Catherine, Euphemia David could.

She had once given him a bone from a mean old black cat’s tail and a single precious hair from her head and told him to go to the cemetery and sit all night on the grave of the richest person buried there—a widow woman who had been just as ornery as that old black cat had been. She told him to put that bone in a little green velvet bag filled with dirt from the freshest and oldest graves in the cemetery, and his last gold coin polished till it shone like the sun, and sew it shut tight using a new needle threaded with her hair. But just before he made the last three stitches he was to stab his finger deep as he could bear with the needle and stick it inside the bag, right up against the bone, and leave it there until the bleeding stopped and the sun rose full in the sky. The next night with the little green bag nestled right over his heart, he walked backward all the way from Trois-Ilets to Fort Royal and into the gaming den with a slice of pepper hot enough to make his eyes stream tucked under his tongue, kept his back to the pit the whole time, placed his bet sight unseen on the red cock with the blue-black tail feathers, and won enough to prevent the plantation from being seized by creditors.

Of course, he did catch a terrible cold sitting up all night in that graveyard, the doctors came and bled him and put mustard plasters on his back and chest, and he was at death’s door for nearly six weeks, but Papa said it was worth it. Mama said he got just what he deserved for dabbling with such deviltry. She had the priest in every day to pray for his tarnished soul and said if he ever had dealings with voodoo and Euphemia David again she would leave him so he would just have to choose between his own bad luck and her and that black voodoo witch and Satan-sent riches. Of course, Papa chose the former, but he was always sniffing and sneaking around the latter like a poor dog outside a locked door behind which a bitch in heat is kept.

But Euphemia David could do nothing for Catherine. She came and laid her snake on Catherine’s chest and it stared my poor, frightened sister right in the face and flicked out its tongue to lick her chin, then slithered back to Euphemia David, right up onto her shoulder, and whispered in her ear that the loas had seen Catherine and decided that she was too beautiful for this world; they wanted her for themselves. She was doomed; there was nothing anyone could do. Death already rattled in her lungs and her heart was withering away fast, growing more sluggish with every hard-won beat, and soon it would stop altogether.

Papa flashed me a warning look, took another sip from his flask, and pointedly turned his back on me as he finished reading Aunt Edmée’s letter in silence so loud it screamed. When he finally turned back around he shook his head. “I’m sorry, Rose, your Aunt Edmée says if for some reason we cannot send Catherine, your little sister, Manette, will do.... I’m sorry, Rose, she says nothing of you.”

“No!” I wailed. “It must be me; it simply must!” I stamped my foot, though I instantly regretted it when I felt the worn, paper-thin sole of my slipper split. I flung myself weeping onto the sofa, crying all the harder when the gilt threads stabbed through my gown, making me feel as though I had thrown myself down in a cactus patch. “I’ll die if I can’t go to Paris! I’ll simply die! I’ll wither away to nothing just like Catherine, then you’ll all be sorry, and it’ll be doubly worse for you, Papa, because you’ll know that you are to blame for not letting me go to Paris and marry Alexandre! You’ll be so brokenhearted you’ll never be able to turn a lucky card again, you’ll lose the plantation, and all your women will leave you because you have no money to give them, and all because you denied me this chance!”

“Really, Rose?” Papa rolled his eyes and took another sip of rum. “My, my, I had no idea you were so passionately fond of Alexandre! When he visited the island you put a black wax conjure ball one of the slaves made for you in his bed and said he was a thoroughly nasty little boy and you hoped someone chopped off his head just like a chicken’s.”

“Oh, Papa!” I cried, and rolled my eyes. “That was only because he kept putting on airs, grand as a little English lord, and calling me stupid and provincial and pulling my hair hard enough to bring tears to my eyes! And I was only five at the time! But now . . . everything’s different! Papa, I would endure anything, even hateful Alexandre, and having my hair pulled, to get to Paris!”

“Are you so eager to leave us then?” Papa teased.

“Oh no, Papa, not you,” I protested, rushing to throw my arms around him, “but I belong in Paris! Paris is the most beautiful, wonderful, and exciting place in the world! And I am fifteen! If I don’t get to Paris soon I’ll be too old to enjoy it!”

Papa sputtered with laughter as he put me from him and turned back to his desk. “Your time will come, Rose, and before your hair turns white and you succumb to rheumatism, I promise you. Now I must answer your aunt’s letter. . . .”

But I didn’t give up. “Papa, please . . .” I wheedled, rushing to stand behind his chair and rub his shoulders, “couldn’t you just mention me to Aunt Edmée? Couldn’t you just remind her that I exist and that Manette has her heart set on entering the convent and becoming a nun? Why, it will simply kill her if she can’t give herself to God, she would rather be torn apart by lions than accept any other bridegroom but Christ, but I . . . I am eager to embrace the world, and Alexandre too, if I must; Paris is worth any sacrifice. Couldn’t you just write something like that, Papa? And maybe you could also tell her that I am pleasingly plump, tall without being too tall, not at all sun browned, I have kept my complexion fair as snow despite the sun that beats down on us like a slave driver, and that I have eyes as fascinating as amber that is thousands of years old flecked with emeralds—a soldier I danced with at the Governor’s ball in Fort Royal told me that, though maybe you shouldn’t mention the soldier to Aunt Edmée, she might not understand . . . or, given her reputation, she might understand too well. . . .”

I nibbled indecisively at my bottom lip. “But you could tell her that I have hair as dark as midnight, wavy and long enough to ensnare and enslave a man—well, maybe you should leave that last part out too, though it was a different soldier who told me that at a different ball, a naval officer, actually . . . I think—and I am endowed with all the charms of youth, a nice bosom, hips that promise my future husband a family of his own someday, and I am a graceful and tireless dancer, with a lively disposition and a great zest for living, and I can also read and write and sew, a little, if I have to, but don’t tell her that my spelling is atrocious and that I can’t sew a straight seam to save my life. Alexandre is just the sort of fussy, nitpicky person to care about silly little things like that!”

Papa put down his pen and turned to stare at me. “This is news to me, Rose. I mean about Manette’s vocation, not your spelling, or the Circean effect you have upon military men; your mother has lost more sleep over that than she has about poor Catherine’s illness. Manette has been sent home from the convent three times for putting spiders in the nuns’ veils and lizards in their beds and if it happens again they will not have her back, not even as a day pupil. Are you quite sure she wants to be a nun? Last time I asked her about her future plans, she said she wanted to cut off her hair, put on breeches, and go to sea and fight pirates, or perhaps become one; she wasn’t quite sure which.”

“Well, tell Aunt Edmée that then!” I brightened. “Oh, Papa”—I hugged his neck and kissed the top of his head even though it meant getting musk-scented powder in my mouth—“that’s even better! Alexandre is far too fastidious to want such a tomboy for his bride! Just tell Aunt Edmée something, tell her anything, as long as it reminds her that I exist and makes her choose me! If you do, and Alexandre agrees to have me, I promise I will send you half of whatever allowance he gives me every month for the rest of your life. Your luck is certain to change sometime.... You could get another charm from Euphemia David, maybe one that doesn’t involve your sitting up all night in the graveyard and catching cold,” I added hopefully.

“Hmmm . . .” Papa tapped his chin thoughtfully. “That is an interesting proposition, Rose. Very well, if I promise to put in a good word for you, will you go away and let me write my letter in peace?”

I hugged Papa’s neck tight and kissed his face a dozen times. “I’m already gone!” I said as I danced out onto the veranda, laughing and twirling as the wind blew the rain sideways, beneath the roof, and over the railing, to slap-kiss me lightly like a naughty child. I caught the little green lizard and cupped him in my hands gently and blew him a kiss and danced him up and down the veranda before putting him safely back on the window. “Little lizard, I am so happy!” I cried in pure delight. “I am going to Paris to be married! My life begins today!”

It never occurred to me that Alexandre might say no; Fate had already written yes in the stars and on my palm at the instant of my birth. It was my destiny!

Two months later a second letter arrived. By then Catherine was already in her grave and Manette had wept so much at the mere suggestion of leaving our island paradise that the doctor feared forcibly uprooting her would be the ruination of her health. Mama, in turn, still reeling from the loss of Catherine, put her foot down. She clung desperately to Manette and insisted that at only eleven she was far too young to even be thinking of marriage. “If Alexandre de Beauharnais wants one of my daughters to be his wife,” she said, “it will have to be Rose!”

I had never been so happy in my life. I won by default, but that didn’t matter at all; I won. I was going to Paris, to answer Destiny’s call; that was the important thing.

Despite some rather strong misgivings about my suitability, Alexandre was willing to accept me since he really had no choice. He had heard that I was a featherhead—he actually wrote that!—frivolous and flighty and prone to putting my heart before my head, provincial and uncultured with no education to speak of and no love of books.

If, as I fear, our marriage turns out badly you will have no one to blame but yourself, he wrote to me.

And, he thought that I, at barely sixteen, was too old for him! He was firmly convinced that a wife should be not even a day less than five years her husband’s junior. Since there were only two years between us he suspected this vital discrepancy did not bode well for our union.

But time was pressing. Alexandre could not afford to wait another year in the hope that Manette’s nerves would settle; indeed he would not have a wife of a nervous, and very likely hysterical, disposition, he said. And he wasn’t inclined to prolong the search and look elsewhere for a bride, like a fairy-tale prince trying to find the girl whose foot fit the glass slipper.

It seemed that money, not the prospect of love and domestic bliss, was at the heart of Alexandre’s eagerness to marry. He could not lay hands on the inheritance his mother had left him until he acquired a wife, as the late marquise believed that marriage would have a good, steadying influence on her son and smooth some of his sharp edges.

If I was the readily available key that could unlock the vault to 40,000 livres per annum, Alexandre was willing to overlook at least a few of my shortcomings, like my age, which I could do nothing about. But he sincerely hoped that I would make it my life’s work to better myself and constantly endeavor to be worthy of him in exchange for the honor he was about to bestow upon me by taking me, albeit reluctantly, as his bride and giving me the title of Vicomtesse de Beauharnais. He was already hard at work, his letter informed me, drawing up a rigorous program of self-improvement to give me as a wedding present along with a forty-volume set of the works of Voltaire and Rousseau, plus supplemental volumes on history, science, and etiquette.

Whoever would have thought that an eighteen-year-old boy could be so stodgy? If I didn’t know better I would have asked Papa if he was certain Alexandre wasn’t eighty. I wanted a husband, not a schoolmaster! I doubted he would be any fun at all! But Alexandre de Beauharnais was the golden gate that led to Paris, so I was willing to be generous and overlook all of his shortcomings.

Aunt Edmée wrote that there was not a moment to lose. Never mind about my trousseau; she would outfit me in Paris. I would be her living doll and she would dress me; it would be her wedding gift to me. Do not delay; just get on a ship and come, she wrote, her words as urgent as voodoo drums in the night.

So I packed everything I possessed and bid everyone farewell and drew in one last long whiff of the sugar-scented air. I was certain I would never come back. When my little cousin Aimee, whose destiny, Euphemia David said, was entwined with mine, wept and clung to me, I reminded her that very soon she too would be boarding a ship bound for Paris. Her father, unlike mine, was a shrewd businessman who could afford to send his daughters abroad to be educated at one of the finest convent schools. I promised faithfully that I would visit her in the convent and take her out for days of fun spent shopping and sipping chocolate at sidewalk cafés, and, when she was older, there would be balls and evenings at the theater. I would even seek a rich and handsome husband for her amongst Alexandre’s friends.

As I stood upon the deck of the Ile de France, with my mulatto maid Rosette, one of Papa’s Fort Royal by-blows, at my side, all our slave women and several free women of color, including many of Father’s mistresses I’m sure, assembled on the wharf to wave good-bye.

All of them were wearing their best clothes: their brightest, gaudiest, most colorful dresses, patterned in vivid checks, bold stripes, or floral prints that looked from a distance like splashes of bright paint; tignons—madras handkerchiefs tied around their heads, the points arranged in intricate up-pointing fashion—and foulards, gay handkerchiefs in colors clashing or contrasting with their gowns, knotted around their shoulders, the unmarried girls seeking a husband leaving the ends of theirs untucked to wordlessly convey their desire to find a mate.

I had grown up watching these women walking the dusty island roads in their bare feet with baskets of fruits and vegetables, crabs and fish, fresh-baked bread and sweet pastries, or laundry balanced on their heads, sashaying and swaying their hips, vying with one another to have the gaudiest, most eye-catching attire and sell the most of their wares by the day’s end. La costume est une lutte—the art of dress is a contest, they always said, words I would cherish and never forget. I would carry them across the sea to France with me and think of them every time I put on my clothes.

As the ship drew out to sea they sang to me “Adieu Madras, Adieu Foulards!,” the age-old island song of farewell that Creole women have been singing for all of human memory to loved ones being borne away by the savage sea, most likely never to return again.

Just for a moment, I thought I glimpsed Euphemia David with her snake around her shoulders, standing in the midst of th. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...