- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

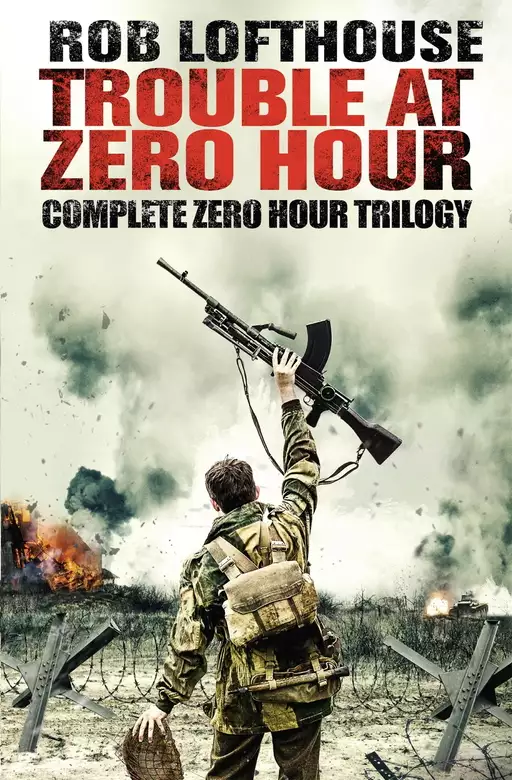

Synopsis

6 June, 1944, somewhere over Normandy. Robbie Stokes sits in a glider, waiting to descend. Ten stomach-churning minutes later, it lands and the first Allied troops tumble out into occupied Europe. It is the beginning of ten months of brutal, relentless conflict that take him from D-Day, via Operation Market Garden and the battle for Arnhem Bridge, to the Rhine Crossing and the final push for victory. Three operations that change the course of the war and test Robbie and his band of brothers to their limits. If they fail, the Allied invasion fails. They must succeed through their longest days.

Release date: August 11, 2016

Publisher: Quercus

Print pages: 592

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Trouble at Zero Hour

Rob Lofthouse

The flight so far had been uneventful, but I was slowly losing faith in the overloaded kite we were all crammed into. The Horsa glider bucked and jerked left and right, as if we were being dragged through the night sky by a large energetic child. My stomach heaved and I silently cursed the airsickness tablets they had given us that were no good to man or beast. The airframe creaked and moaned with all the forces imposed on it. With every creak of timber and aluminium, I waited for the glider to disintegrate. It looked great sat in the hangar back at RAF Tarrant Rushton in Dorset. It even looked a pretty awesome concept on the sketches we were shown, but it dodged and weaved so much as it was dragged through the sky by the Halifax bomber out front, I was worried when we released ourselves from its umbilical, we would plummet to the ground far below with the elegance and grace of a house brick.

Sleep seemed impossible, yet some of the boys managed it. How on earth could they sleep at a time like this? Never mind crashing at any moment, we still had the Germans to contend with. As I thought about our daring plan, the more absurd it became. We were to land our gliders next to a canal bridge and jump out and capture it in the vain hope Jerry would be scratching his arse in bed while we did it. Maybe the most absurd plans during war were the most successful. I glanced around the dim interior of the glider; most just sat there, eyes open, deep in their own thoughts. Boots tapping and knees bouncing – with nerves no doubt. I was not any better. I couldn’t read their facial expressions. The camouflage cream was smeared on heavily, and I could just make out the moustaches on some of them.

Conversation was almost impossible. The glider may have been without an engine, but the air outside screamed past with a horrendous din. In the confined space it was rather warm. I was sweating like a beast in all my gear. Cam cream and sweat was causing my eyes to sting. I made a fruitless attempt to ease the stinging with my sleeve. My helmet was firmly in place, crude strips of green material attached to break up its outline. Heavy hobnailed combat boots were standard issue. Thick woollen socks made them as comfortable as they were going to be. Canvas gaiters were strapped around the tops of the boots, more for decoration than anything else, since I always ended up with wet feet. My combat trousers were rough, heavy and brown, held up with braces. My underwear was a basic affair, light shorts with an undershirt. I wore my heavy Denison smock over the top, which weighed a ton with everything crammed into the pockets. Equipment was basic, given the limited space we had in the glider. A canvas belt, shoulder straps, plus two large ammunition pouches on the front. Worn high on my back, I had a small canvas backpack, which only really had room for food but was filled with more equipment required for the mission, including wire cutters and raincoat. No luxuries, we just didn’t have the room. Digging into the base of my back was my entrenching tool, a small lightweight shovel-cum-pickaxe. We all had one, so if we were static for a considerable period of time, we had the means of digging in to protect us from artillery fire and the like.

My personal weapon was a Bren light machine gun. A beast of a weapon. Its only real drawback was that it could be rather cumbersome, especially when moving around in confined spaces such as buildings. Its large curved thirty-round magazine protruded from the top, feeding it with .303 calibre rounds. The .303 could put an elephant down, no problem, let alone a man. I had an extra five magazines in my pouches, and every non-gunner in the platoon carried another four magazines for the gunners. The company commander, Major Anthony Hibbert, wanted maximum firepower, but we also had to be mindful of our weight for the glider. To top off our combat loads, each man had up to nine grenades, since they were excellent at dealing with houses and stubborn Jerries in trenches, really taking the fight out of them. Each platoon also had a two-inch mortar, which the serjeant controlled. For good measure, the riflemen in the platoon also had to carry two mortar bombs each. They carried all the extra ammunition in canvas sacks, enabling them to drop it off at positions when required. Despite my reservations, I was quietly confident we would give Jerry a proper good hiding, should they contest what we had in mind.

Strapped to a wall of the glider, I tried to adjust myself. I accidentally kicked a shin belonging to my platoon serjeant, Sean Wardle. In a faint glow of red torchlight I could make out his glare at me. It was a menacing, murderous glare, the red glow and his heavily cam-creamed face making him look all the more sinister. I smiled sheepishly and mouthed an apology, trying my hardest to break free of his gaze. Sean was a firm but fair man. His method of leadership was rather brash, but he would take time to show you how he wanted stuff done. If you put your hand up and admitted you didn’t understand or had forgotten what he wanted you to do, that was fine; he would show you again. I never pretended to be the best soldier, since there were plenty of men more worthy of that title, but if I tried to cuff it, and everything then went tits up, he would be on my case like you wouldn’t believe. Very rarely did he drink with me or the other lads in my section of the platoon. It wasn’t because he didn’t feel us worthy of his company, he just had enough on his plate. He wasn’t on all the lads’ Christmas-card lists either, but as far as I was concerned, it was a fair trade-off.

Sean returned his gaze to a torchlight-illuminated map in the hands of our platoon commander, Lieutenant Bertie Young, who was sitting next to him. Young was no clown; very intelligent, very fit and a good soldier. He was daring and reckless in equal measure. His devil-may-care attitude to life was rather fun but bloody tiring. He endeavoured to have his platoon doing the risky parts of any exercise, the toughest of the assignments dished out by Major Hibbert. Consequently, our level of physical fitness as a platoon was very high. Where Young got his energy from was anyone’s guess. Sean spent most of his time keeping him out of trouble.

Sitting just out of the glow of Young’s torch was my section commander, Corporal Terry Thomson. Terry was pretty much cut from the same cloth as Sean. They were long-term friends, but when it came to operations like this, you could see the professional boundary between corporal and serjeant. Like Sean, Terry was a family man, but had a more maverick streak. He had the same leadership style as Sean, but the rogue mindset of Young, a dangerous combination, some might say. But as far as I was concerned, Terry was a good guy to have in your corner.

Watching the three of them try and converse above the awesome din of the flight became a rather pleasant distraction. Young would shout like a madman, Sean and Terry nodding. Serjeant and corporal both knew what was required; Major Hibbert insisted we all did. Our rehearsals for tonight had been detailed, to say the least. Things could change in the blink of an eye, so even the newest private soldier had to understand clearly what the mission was, come what may.

My focus on their discussion was broken when the glider began to bob and weave heavily again. Another flicker of light caught my attention. In the glow of a match I could make out the heavily cam-smeared profile of Tony Winman. He was the same age as myself, twenty-three, and hailed from Southampton. How on earth he had managed to end up in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, God only knows. The story I heard was he moved up to St Albans at the start of the war, since Southampton was getting hammered by the Luftwaffe. St Albans was a safer bet for his mother and sister too. He had only joined the Ox and Bucks about a year ago, and was still very much one of the new boys.

Something thick and heavy clashed against the right side of my helmet, making me jump and feel rather agitated. The solid mass happened to be the dozing head of Frank Williams. This guy could sleep on a chicken’s lip. A London boy, he was a bull of a man. But despite his intimidating frame, he was a wonderful guy, the platoon clown. His antics in and out of barracks would drive Sean to despair sometimes, which would do nothing more than fuel Frank’s thirst for larking about. Without ceremony, I shoved Frank’s head away from mine, and his bonce crashed into Dougie Chambers, on the other side of him. Even over the din, I could make out Dougie’s curses. Frank emerged from his slumber. Sean slowly shook his head. Frank gave an exaggerated yawn and stretched his arms wide, pinning me and Dougie against the wall. Frank flinched as Dougie jabbed at his midsection. I just sat there, waiting for it all to subside, Frank’s huge arm across my chest. Besides, I couldn’t get a good jab in. Off to my left, towards the tail of the glider, I noticed Lance Corporal Bobby Carrol dozing away. Second-in-command of my section, he was also company fitness instructor. Frank lit a cigarette, and proceeded to blow smoke rings at those he knew were non-smokers. I noticed Sean and Young look at each other, shaking their heads and rolling their eyes.

A barely audible shout came from the cockpit: ‘Action stations!’ This was passed down the aircraft, and the professional in all of us came to the surface. Cigarettes were extinguished, torches put out, maps put away, dozing soldiers shoved awake. I got myself sorted, ensuring my helmet was correctly fitted, my seat harness secure, Bren stowed muzzle up between my knees. My stomach began doing somersaults; clammy hands gripped the gun. I couldn’t help myself, but my left knee was bouncing up and down like crazy. I fought hard to prevent it, peering around at the other faces in the gloom. Some had bouncing knees too. We were really doing this. We were at the tip of the spear for the invasion of Europe. The Germans had had things their way for the last five years, and we were now back to tear things up and kick some arse. I found myself thinking of Mum and Daniel, my younger brother by two years. I knew Mum wasn’t too pleased about me joining up. Daniel was now a cripple. He had been at Dunkirk and lost a leg in a Stuka attack while he was waiting on the beach to board a ship. Like him, I felt I had to do my part, like my dad had in a mud-smeared shit hole called Passchendaele all those years ago. I did not regret my decision; I just wanted to get on with it. Some of those around me had combat experience already, but for the majority this was about to become a whole new adventure.

My stomach lurched into my throat as the glider was released from its tow rope. The sudden drop in altitude caused us all to momentarily leave our seats. Good job we had harnesses on, since some of us would have got a face full of wood from the roof of the aircraft. We were coming down hard and fast. Through small portholes in the side of the glider, a rare glint of moonlight revealed a few features of the Normandy fields below. The aircraft bucked and swooped, left and right. I felt like I was on a fairground ride. Every time my stomach settled, we would drop suddenly again. I was not looking forward to the landing, if we were going to do it at this speed. As we got lower, I could just make out the tops of trees whipping past. They got thicker and darker as we descended further. This was going to be one rough landing. I caught a sudden glimpse of moonlight reflecting off what appeared to be water, before yet more trees whipped past. I glanced over at Sean. He didn’t appear to be enjoying the experience either, but he did manage to give me the thumbs up.

‘Brace!’ came another shout from up front. We hit the ground big time. The impact of the landing took all my breath from me. My testicles felt like they were in my ammunition pouches. Aluminium buckled all around, screaming under the sheer velocity of the landing, timber creaking and splintering as the aircraft began to disintegrate. Amid the cacophony of our crash landing, the profanity coming from my fellow passengers was biblical to say the least. I had a few choice words for those who had dreamed up this absurd idea, and maybe a few more for the aircraft’s inventors. A sudden rush of cold night air hit me as the tail of the glider gave up its fight to cling on, cartwheeling out of sight. We were going to die before it had even begun. Then the whole experience thundered to a complete stop, metal and wood groaning.

All was quiet in what was left of our glider. I was suddenly overwhelmed by fatigue, and as Mistress Sleep seduced me, I could faintly hear a foreign voice outside.

‘Fallschirmjäger! Fallschirmjäger!’

A rough hand whizzed across my face in the darkness.

Fallschirmjäger. I had first heard the word a few hours earlier during Major Hibbert’s mission briefing at RAF Tarrant Rushton. I tried to remember what it meant. Paratroopers, that was it. And that was us: D Company, 2nd Battalion, the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. Although the battalion was a glider force, we were considered paratroopers, since it was intended that we work alongside parachute troops, a newish breed of soldier in Britain based on Hitler’s very successful, almost legendary airborne forces.

I’d joined up at a recruiting point in High Wycombe train station. I had no clue how many battalions were in the regiment, but 2nd Battalion hadn’t been my first inclination. However, I’d been impressed that, unusually, membership of the battalion was voluntary due to the rugged nature of its envisaged jobs. They’d wanted the fittest and toughest of the bunch. You couldn’t join if you had ever suffered from malaria, which meant the battalion was a little short of boots on the ground as it had undertaken tours of the Far East and North Africa, sufferers being reallocated to non-airborne battalions in the regiment.

When people asked me why I’d enlisted I’d tell them about my brother Daniel losing a leg at Dunkirk and the injuries sustained by my father at Passchendaele during the Great War. But, in truth, I think it was a sense of adventure that prompted me to join up as much as anything. My job at the brewery had been fine, but my life had been little more than drinking and working. A beaming, very smart, clean-shaven but scarred recruiting serjeant loaded with medals had signed me up and told me that the first lesson of soldiering in the regiment was they spelt sergeant with a ‘j’.

It was a different serjeant with a ‘j’ who led us into the hangar at RAF Tarrant Rushton one night almost two years later when our training was almost complete. The hangar was huge, stuffed with six Halifax bombers and six Horsa gliders. We were familiar with the machines having trained on them at Bulford in Wiltshire, on the edge of Salisbury Plain. As almost two hundred of us shuffled our way inside, skirting the tail of a Halifax, and saw Major Hibbert, Captain Brettle and Company Serjeant Major Jenkins, together with all the platoon commanders and other serjeants, it became clear that this was to be no ordinary operation. It was something big. The one we’d known was coming. The one we’d sensed in the tension around us. Getting the battalion down into Dorset had been a mission. The volume of military traffic on the roads between Bulford and Tarrant Rushton had been immense. And it hadn’t just been British units caught up in the melee of convoys, we’d encountered American and Canadian traffic control parties at road junctions all the way down. We were on the cusp of one hell of a job, speculation was rife but facts had been scarce.

The officers stood in a three-sided square around an area of dirt and grass, the odd sketch and blown-up photographs taken from the air. Low whistles could be heard coming from people’s lips as we surrounded the huge model on the hangar floor. ‘Fuckin ’ell,’ Frank Williams murmured, ever the diplomat. Level-headed Dougie Chambers looked at him in admonishment.

‘Welcome, gentlemen,’ Major Hibbert bellowed. ‘Serjeant Major, please put them in their order of march. Thank you.’

It took a while for Jenkins to line us up in front of the model. The platoon commanders and other serjeants then joined us on the floor, leaving Hibbert and Brettle standing before everyone. A deathly silence descended. You could have heard a mouse fart in that hangar.

‘Thank you, Serjeant Major,’ Hibbert began. ‘Gentlemen, we have all been training long and hard for this opportunity, and I intend not to keep you waiting any longer. Tonight we are bound for Normandy in northern France. We will be leading the way, the very first unit to kick in the door of Hitler’s supposed Fortress Europe.’ He smiled, seeming to enjoy releasing the bombshell. ‘Before we go into the pleasantries, I must ensure housekeeping rules are in place. First of all, Serjeant Major, should anyone be seen or heard entering this hangar while my orders are in progress, would you be so kind as to remove the name cards from the model. Any such person is also to be held here until after our departure tonight. Understood?’

Jenkins nodded as Hibbert swivelled to face the model sideways on.

I’d taken a chance to study the details of the model for the first time. It was the biggest model I had ever seen. It was actually two models of equal size, set next to each other. The one on the left showed our primary target area, the other showed nearby geography. It was the Normandy coastline, that much was clear, and the clustering of name cards on the left-hand side gave away our target area. The towns of Caen and Ranville had been labelled, as had a beach called ‘Sword’, with an arrow indicating which way was north. The detail was very impressive; even the layout of fields was shown, the tiny hedgerows separating them looked just like the real thing. There was a single orange card – bright orange – which we took to be the main prize. It was located slightly inland to the south-east of Sword beach and it said ‘Bénouville’. Just two of the cards puzzled me: ‘Ham’ and ‘Jam’.

‘Gentlemen,’ Hibbert continued, ‘you are about to receive orders for a deliberate glider raid onto two bridges in Normandy tonight.’ Brettle reached down to the hangar floor and picked up a snooker cue. He used it to point at the ‘Ham’ and ‘Jam’ cards, which sat on two parallel bits of blue ribbon running from the coast to the city of Caen. Everyone from corporal upwards began to scribble furiously in notebooks. Hibbert suddenly looked very smug, like a child opening Christmas presents. It made my stomach turn a little. He went on to describe the model, as the flustered Brettle frantically tried to keep up with his cue: every card, every town, every village, every road, every stretch of water, every feature. Hibbert missed nothing. Nothing. To begin with, it felt like a father introducing his child to a model in his back garden, the child expected to run his toy cars about. But it quickly sank in that this was no game; the area the model represented would shortly turn into a very real battlefield.

He asked for questions. As one, everyone around me shook their heads. Hibbert wasn’t happy with this, a sinister grin stretched across his face. So he picked people out, one by one, bombarding them with questions of his own. What had he called this? What did that represent? Why was the card orange? What were Ham and Jam?

He then briefed us on the general characteristics of the area: the type of farming, market days, population before and during the German occupation, condition of main roads and tracks, tide timings of rivers, their current average speed of flow, their width, barge traffic before and during the occupation. My head began to hurt: were we going to attack the place or build a replica of it in Dorset?

Unexpectedly, he then handed the floor over to a young captain from the troop of Royal Engineers attached to the company for this mission. The engineer clambered to his feet and hobbled forward, probably fighting off pins and needles from sitting on the hangar floor. He thanked Hibbert, then launched into detail, prompting Brettle to recommence darting the cue around.

‘Gentlemen, as the major explained, our mission is to take and hold the two bridges on this road linking Bénouville to Ranville and to stop German reinforcements making it to the landing beaches, here. The Bénouville Bridge, which is named after the village behind it, will be known as objective Ham. Running over the Caen Canal, the bridge is one hundred and ninety feet long and twelve feet wide. There’s a bridge-raising mechanism and control room on the east bank. The bridge is capable of holding the weight of any armoured vehicle currently fielded by both enemy and friendly forces.’

There was a horrible feeling in my gut at that moment. None of us wanted to hear about tanks that might give us trouble.

‘And as the major explained,’ he continued, ‘there is another bridge nearby, Ranville Bridge, running over the River Orne, just a quarter of a mile to the south-east, which is known as objective Jam. It is three hundred and fifty feet long and twenty feet wide. It can take the weight of all known armour. Later on, my chief bomb maker, Staff Sergeant Bamsey –’ he pointed at Bamsey in the crowd ‘– will talk about demolition.’

He nodded to Hibbert, then rejoined the rest of us. ‘Any questions before we continue?’ Hibbert asked deliberately.

‘Will enemy armour be around, sir?’ a nervous voice behind me asked.

‘One thing to the Germans’ credit is their battlefield discipline. We cannot deny them that. No matter what the vehicle, whether it be a motorbike and sidecar or their heavy armour, they will conceal it if stationary for more than ten minutes or so. Our sources cannot give us a firm picture as to the armoured threat in the immediate region. This is why I have insisted we take as much armour-defeating capability as our gliders will allow. Also remember our time on Salisbury Plain with enemy anti-tank weapons. Those weapons might be for the taking in Normandy, perhaps under repair or refitting. The German armoured forces in Russia have been badly mauled, and I would not be surprised if Normandy was being used as an area for rest and repairs.’

There were murmurs all round. The answer was ruthlessly comprehensive. I realized for the first time he wasn’t referring to notes. He already knew every bit of fine detail relevant to the operation.

But I was also suspicious. If I’d been giving out orders, the last thing I’d have talked about was vast hordes of Tiger tanks, even if I’d known they were hiding in hedgerows around the target.

‘Let me sum up the overall situation regarding enemy forces,’ he concluded. ‘The German Army has occupied this real estate since the summer of 1940. They have allocated a lot of time, money, resources and manpower in the form of slave labour to the area, so as to ensure we cannot return. Tonight, however, that all changes.’

There were nervous chuckles.

He continued: ‘The lion’s share of German forces is currently committed to their Russian and Italian areas of operation. Up to 80 per cent of them are committed to the Russian front. The German high command have taken their eye off the ball with regard to France. Convinced an Allied invasion force will eventually try to push across the Dover–Calais axis, the Germans have mustered their reserve panzer forces in the Pas-de-Calais region, leaving a very large proportion of the French coastline poorly defended.’

Heads bobbed all round me.

‘We do have to take care of enemy forces in the immediate target area,’ he continued. ‘As of midday today, intelligence sources have indicated that fifty-plus enemy troops are guarding each of the bridge sites. But the troops are of low quality, tending to consist of wounded back from the Eastern Front, plus prisoners of war pressed into service: Polish, Russian, even French.’

Personally, I always had some sympathy for the prisoners of war, guessing they had joined the enemy to avoid a worse fate.

‘Their headquarters and centre of mass are in Ranville,’ Hibbert advised, prompting Brettle to wave the cue again. ‘Their morale is mixed at best. Their weapons are in general a mixed bag, often outdated. There is however an anti-tank gun sited on the east bank of objective Ham. Regardless of age, it is a deadly weapon. We don’t know its calibre, but we must quickly render it useless to the enemy. We don’t necessarily want to destroy it, as it may be of some use to us. You never know, some of you may get on-the-job training with the gun. But if you should acquire the weapon, don’t let your guard slip down through overconfidence. Regardless of the level of success you achieve at any time, you must always stay on your game. Understood?’

Everyone nodded again.

‘Now let’s talk about friendly forces. The first friendlies should be with us just before dawn, in the form of 7 Para. They will parachute into the drop zone nearest us, just as other elements of 6th Airborne Division arrive in a drop zone further away. Pathfinders will be in the area, but I doubt they will reveal their presence until the drops begin. As 7 Para make their way into our perimeter, coming through objective Jam, we will grow stronger as an overall force and should be able to hold the position until relieved by forces landing at Sword. The beach is just a few miles away, so if all goes well, it won’t be too long after first light before landing forces are with us. Any questions?’ There were none.

‘Gentlemen, your mission is to seize and hold bridges Ham and Jam. Be prepared to defend against enemy counter-attack until relieved, in order to allow friendly forces to exploit out of the Sword bridgehead towards Caen.’ Only the scraping of pencil lead on paper broke the brief silence. ‘I repeat, your mission is to seize and hold bridges Ham and Jam. Be prepared to defend against enemy counter-attack until relieved, in order to allow friendly forces to exploit out of the Sword bridgehead towards Caen.’ It was traditional to give the mission statement twice, so no one was in any doubt.

He went on to provide minute details as to how the mission should be achieved: who would do what within a preliminary movement plan. The entire glider force was to land on a narrow slip of land between the two bridges, he explained. It would be tight, especially given gliders have no brakes. I suddenly wondered why on earth anyone had come up with a plan involving gliders before realizing a silent glider landing would get a lot of people down at the same time with no parachute canopies for the enemy to spot; the landing should have the advantage of complete surprise. Once we were out of the gliders, Hibbert would take half the force, including me, to Ham. Brettle would take the remainder to assault Jam, engineers would be split equally between the two halves. Brettle and Hibbert explained how the enemy sentries would be overwhelmed with thunderclap surprise. The bridges would be captured before their dozing defenders could fall out of their bunks. It was possible for the distribution of forces to be revised at any time, he concluded.

It was my kind of plan: plain and simple, and easy to remember. Kill the bad guys, hold the bridge until relieved.

Serjeant Major Jenkins appeared before us. ‘When we land, there can be no fucking about, dealing with the dead and wounded, especially if we crash-land or come immediately under fire. You get out of the bloody plane, and you deal with the enemy first, is that clear?’

A united chorus of ‘Yes, sir’ thundered through the hangar.

‘You don’t stop for no one. Clear and hold your objectives before you do anything else. When the situation allows, I will put men to the task, if we have to deal with casualties, both friendly and enemy. If I tell you to patch up a wounded enemy soldier, I want none of your fucking wisecracks; you just get it done. Fuck me off, and that enemy soldier will be patching you up. All casualties will be brought to the gliders.’ I’d have bet money on no one risking his annoyance by disobeying him. ‘Same with prisoners,’ he advised. ‘If the enemy drop their weapons, make the correct call. Clear them of any weapons and ammunition. Bring surrendered enemy to the gliders so I can take them off your hands. And when the situation allows, I want all enemy weapons and ammunition to my location, so we can distribute them around our perimeter. We may be there some time, with the enemy trying their bloody hardest to get them bridges back. Any questions?’ There were none.

Hibbert introduced Staff Sergeant Bamsey. As Bamsey climbed to his feet, he hauled up a few sandbags. Once standing at the front, he slowly and methodically emptied them. There were different-sized blocks wrapped in black gaffer tape, wires of various colours hanging out. He arranged the blocks in two piles on the ground before clearing his throat. ‘Gentlemen, these are demolition measures.’ His accent was the thickest Welsh I had ever heard.

Almost as one, everyone leaned forward.

He lifted one of the contraptions. ‘German explosive. Have a look, pass it round.’

There was a collective gasp as he’d tossed it in the air. We’d no experience with explosives, no idea how volatile they might be. But a lad in the crowd caught the contraption cleanly, and o

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...