1

Early Coralroot

Corallorhiza trifida

Coral was pregnant then. She hid it well in a dress she had found in the road, sun-bleached and mud-dotted, only a little ripped. The dress billowed to her knees, over the tops of her boots. She was named for the wildflower which hadn’t been seen since before her birth, and for ocean life, poisoned and gone. It was too dangerous to go to the beach anymore. You never knew when storms might come.

Though they were going—to get a whale.

A boy had come from up north with a rumor: a whale had beached. Far off its course, but everything was off by then: the waterways, the paths to the ocean, its salt. You went where you had to go, where weather and work and family—but mostly weather—took you.

The villagers around Lake Erie were carving the creature up, taking all the good meat and fat. The strainer in its mouth could be used for bows, the bones in its chest for tent poles or greenhouse beams.

It was a lot of fuel for maybe nothing, a rumor spun by an out-of-breath boy. But there would be pickings along the road. And there was still gas, expensive but available. So the group went, led by Mr. Fall. They brought kayaks, lashed to the top of the bus, but in the end, the water was shallow enough they could wade.

They knew where to go because they could smell it. You got used to a lot of smells in the world: rotten food, chemicals, even shit. But death... Death was hard to get used to.

“Masks up,” Mr. Fall said.

Some of the men in the group—all men except Coral—had respirators, painter’s masks, or medical masks. Coral had a handkerchief of faded blue paisley, knotted around her neck. She pulled it up over her nose. She had dotted it with lavender oil from a vial, carefully tipping out the little she had left. She breathed shallowly through fabric and flowers.

Mr. Fall just had a T-shirt, wound around his face. He could have gotten a better mask, Coral knew, but he was leading the crew. He saved the good things for the others.

She was the only girl on the trip, and probably the youngest person. Maybe fifteen, she thought. Months ago, she had lain in the icehouse with her teacher, a man who would not stay. He was old enough to have an old-fashioned name, Robert, to be called after people who had lived and died as they should. Old enough to know better, Mr. Fall had said, but what was better, anymore?

Everything was temporary. Robert touched her in the straw, the ice blocks sweltering around them. He let himself want her, or pretend to, for a few hours. She tried not to miss him. His hands that shook at her buttons would shake in a fire or in a swell of floodwater. Or maybe violence had killed him.

She remembered it felt cool in the icehouse, a relief from the outside where heat beat down. The last of the chillers sputtered out chemicals. The heat stayed trapped in people’s shelters, like ghosts circling the ceiling. Heat haunted. It would never leave.

News would stop for long stretches. The information that reached Scrappalachia would be written hastily on damp paper, across every scrawled inch. It was always old news.

The whale would be picked over by the time they reached it.

Mr. Fall led a practiced team. They would not bother Coral, were trained not to mess with anything except the mission. They parked the bus in an old lot, then descended through weeds to the beach. The stairs had washed away. And the beach, when they reached it, was not covered with dirt or rock as Coral had expected, but with a fine yellow grit so bright it hurt to look at, a blankness stretching on.

“Take off your boots,” Mr. Fall said.

Coral looked at him, but the others were listening, knotting plastic laces around their necks, stuffing socks into pockets.

“Go on, Coral. It’s all right.” Mr. Fall’s voice was gentle, muffled by the shirt.

Coral had her job to do. Only Mr. Fall and the midwife knew for sure she was pregnant, though others were talking. She knew how to move so that no one could see.

But maybe, she thought as she leaned on a fence post and popped off her boot, she wantedpeople to see. To tell her what to do, how to handle it. Help her. He had to have died, Robert—and that was the reason he didn’t come back for her. Or maybe he didn’t know about the baby?

People had thought there would be no more time, but there was. Just different time. Time moving slower. Time after disaster, when they still had to live.

She set her foot down on the yellow surface. It was warm.

She shot a look at Mr. Fall.

The surface felt smooth, shifting beneath her toes. Coral slid her foot across, light and slightly painful. It was the first time she had felt sand.

The sand on the beach made only a thin layer. People had started to take it. Already, people knew sand, like everything, could be valuable, could be sold.

Coral took off her other boot. She didn’t have laces, to tie around her neck. She carried the boots under her arm. Sand clung to her, pebbles jabbing at her feet. Much of the trash on the beach had been picked through. What was left was diapers and food wrappers and cigarettes smoked down to filters.

“Watch yourselves,” Mr. Fall said.

Down the beach they followed the smell. It led them on, the sweet rot scent. They came around a rock outcropping, and there was the whale, massive as a ship run aground: red, purple, and white. The colors seemed not real. Birds were on it, the black birds of death. The enemies of scavengers, their competition. Two of the men ran forward, waving their arms and whooping to scare off the birds.

“All right, everybody,” Mr. Fall said to the others. “You know what to look for.”

Except they didn’t. Not really. Animals weren’t their specialty.

Plastic was.

People had taken axes to the carcass, to carve off meat. More desperate people had taken spoons, whatever they could use to get at something to take home for candle wax or heating fuel, or to barter or beg for something else, something better.

“You ever seen a whale?” one of the men, New Orleans, asked Coral.

She shook her head. “No.”

“This isn’t a whale,” Mr. Fall said. “Not anymore. Keep your masks on.”

They approached it. The carcass sank into the sand. Coral tried not to breathe deeply. Flesh draped from the bones of the whale. The bones were arched, soaring like buttresses, things that made up cathedrals—things she had read about in the book.

Bracing his arm over his mouth, Mr. Fall began to pry at the ribs. They were big and strong. They made a cracking sound, like a splitting tree.

New Orleans gagged and fell back.

Other men were dropping. Coral heard someone vomiting into the sand. The smell was so strong it filled her head and chest like a sound, a high ringing. She moved closer to give her feet something to do. She stood in front of the whale and looked into its gaping mouth.

There was something in the whale.

Something deep in its throat.

In one pocket she carried a knife always, and in the other she had a light: a precious flashlight that cast a weak beam. She switched it on and swept it over the whale’s tongue, picked black by the birds.

She saw a mass, opaque and shimmering, wide enough it blocked the whale’s throat. The whale had probably died of it, this blockage. The mass looked lumpy, twined with seaweed and muck, but in the mess, she could make out a water bottle.

It was plastic. Plastic in the animal’s mouth. It sparked in the beam of her flashlight.

Coral stepped into the whale.

2

Mr. Fall

Autumnus

They were pluckers. Their work was seasonal. They followed the plastic tide. After the floods destroyed the coasts, rewrote the maps with more blue, something was in the water that lapped at Ohio and Georgia and Pennsylvania.

Plastic.

People learned quickly that it was useful. It had to be.

China had stopped accepting electronics and batteries to recycle. Too expensive to process, too much of a waste of electricity and precious clean water. Acid seeped into the earth, and people held on to their computers and phones long past their breaking, knowing there would be no others. The people out in the country became a people of hoarders. They became junk lords. The center of the United States, which many people had not bothered with before, became the great vast orchards of scrap.

Scrappalachia.

The factories had closed to try to stem pollution, all the countries—even the States eventually—moving to ban new polymers. There would be no new water bottles, no take-out containers, no packaging or stereos or ball pits or flip-flops or dashboards or sunglasses or tubs.

But plastic lasted. It could be shredded, melted, pressed into bricks. The bricks could rebuild the police stations, the government offices that had been torn down in riots or wiped out in waves. As for everyone else? Their lives were almost entirely junk. Finding and trading, making do, discovering new uses, haggling prices.

Mr. Fall was old enough to remember the water.

Mostly he remembered the news. The television blared in his household, telling his family...something. What, Mr. Fall didn’t remember exactly. Something about a warning, how they needed to get out. Evacuate. They didn’t have enough time, or they hadn’t listened. Red bars scrolled across the bottom of the TV; a beeping sound emitted from it. Then the water poured in from under the windows.

Mr. Fall remembered the rain: hammering on rooftops, streaming past the overhang. The pounding of their feet to the attic where his family ran, hiding from the water, climbing up and gathering to await rescue, which never came.

Water followed them. The TV was knocked off the counter. When Mr. Fall looked back, it sparked, went to black. His father yanked him upstairs, water trailing like a puppy. Mr. Fall ran as fast as if he was escaping a beating. Faster. So fast, he fell to his knees and crawled.

Water was coming.

He had never liked the attic, as he had never liked the basement. Avoided both. Both smelled funny, of monsters and darkness, spiderwebs and shadows. The basement shelves crowded with food they didn’t eat, murky jars of things that went bad. After the floods, they would find some of these jars bobbing on the surface, dusty glass finally washed clean. His family would grab them. Eat every one.

As for the attic, junk filled it, broken items that had never had a use, or that seemed to have outlived their usefulness. His life, his life of junk, was only just beginning.

Uncle hung a white sheet out of the attic window with their names spray-painted in black and SOS. Mr. Fall didn’t know what those letters meant. Nobody was answering his questions. He knew it was something to do with ships, the navy—which would be gone soon, along with airplanes except for government and medical use, the internet, commercial trucking.

Whatever SOS meant, it didn’t work.

They waited in the attic for a long time. Uncle had also spray-painted the family’s ages, as if that would help. He was 17. Mr. Fall was 5. His brother, 12. He grew hungry, but there was nothing to eat. He grew too tired to be afraid and fell asleep, curled against a big green jacket, which smelled of mice and bore their teeth marks.

When he woke up, the world was water.

3

Coral

Coral waded in the water, waist-deep. Her boots only reached her thighs, and when she came home, Trillium would know by her damp clothes how deeply she had gone in.

Her pack felt full already, but something bobbed in the river before her. Everything was hot: her body, the river, the air. The setting of the sun would offer little relief, the sky flushed orange and pink. It was brilliant, as was every sunset. Mr. Fall said there used to be a color called Dayglo that would burn so brightly it hurt your eyes. Coral didn’t understand how a color could just disappear. But whole cities could disappear. Coasts could disappear. Trees and flowers and animals.

Children could disappear.

She grabbed the plastic in the river. It was thicker than the flimsy water bottles. This object was rectangular, open at one end. It had a hole in its side, punched or broken through. But a hole could be mended. The whole thing could be cut up into soles for shoes, or it could be ground to pave a path or fill a mattress. Really, though, she knew what would happen to the plastic. It would be pulverized, melted, and pressed into bricks.

She might know the small hands that pressed it.

Her family had camped in the junkyard for a long time. Maybe too long. But as long as plastic washed up in the river, they could stay, in the southeastern part of what had been Ohio. Trillium felt uneasy about staying in one spot for too long—his business thrived on the novelty of a new place, new people, new skin—though Mr. Fall didn’t mind it. But Coral needed to stay. The bus tires could rot in the dirt, but that was the only danger in staying, she thought.

She needed to be rooted. Her son had to know where to find her.

She climbed out of the river, and stood on the bank down the hill from the junkyard. The river had a smell. Different, depending on the day. The white in the water was not surf, not cresting foam—but plastic. People waded in the river below. New Orleans, the rest of the crew. They trudged, heads down as their arms swept the water. Most carried nets woven from plastic bags. Packs strapped to their shoulders bulged with the things they had pulled from the river. Plastic was light, but when the backpacks grew heavy, the pluckers were supposed to return home, dump their finds, and return to the river. Repeat until dusk. Every day.

The bus where Coral lived was parked down an access road that led to an old quarry. A small hill separated the bus from the rest of the junkyard, enough to have some space and privacy, but not too far that customers couldn’t find it.

The bus had been a school bus. Coral tried to imagine a time when buses would have been so plentiful that children rode them every day, gas flowing freely. The bus had belonged to Mr. Fall’s school, back when he had been a real teacher. No, someone higher than a teacher. What was the word? Someone who, when the wildfires came, took a bus that didn’t even belong to him, rounded up all the children he could and drove them out through the smoke. It took all the gas they had. He had never driven a bus before.

It had always been black, but many years ago Mr. Fall had painted a rainbow stripe around the bus to help teach color names. She knew he had scavenged and saved for the paint. Trillium hated the stripe, but it was useful. The rainbow bus, people could say. When it was parked, Trillium hung his sign. Tattoos.

Trillium had his shop in the back. They lived up front, sleeping on a bed that folded out from the wall like a jointed, wooden toy Mr. Fall had pulled from the water for Coral when she was a child. He had made it move, pulling a lever on its back to kick out the legs—and then the whole thing had rotted, collapsing into sticks as she reached for it.

As she approached the bus, water squelched in her boots. She dropped her pack into the dirt. She had been carrying the big plastic piece with the hole in its side. This she set down more gently, sliding it under the bus. Sometimes Mr. Fall slept there, if it hadn’t rained, and if he wanted to give her and Trillium space, but he had placed his bedroll on the far end, under the driver’s seat. She took off her wet boots and wrung the hem of her clothes.

She heard a laugh from inside. Familiar.

Foxglove.

The accordion doors were open. Coral went up the steps into the bus. At the back, a girl with long auburn hair lay on her stomach on a table. She was naked from the waist up. Her hair streamed over the edge of the table like rainfall, hiding her face.

“What has he done to you this time?” Coral asked.

The girl lifted her head.

Trillium leaned over her back, the tattooing needle still in his hand, though he was done. Coral could see a patch of Foxglove’s skin glistened. Trillium wiped the patch carefully with a rag. “You’re soaked,” he said to Coral. “You went deep.”

“There was something good to get.”

“Coral,” Foxglove said. “I wish someone would tattoo me with a nice name like that.” She sang it out. “Coral.”

“Let me see that tattoo.” Coral peered over the girl, her skin smooth except for the tattoos, like the barcodes Coral had seen on sturdier plastic. The ink was mostly black, and all of the girl’s dozens of tattoos were names: Alexandria, Osaka.

Hague. That was the new one.

“What’s a Hague?” Coral asked.

“A very rich man,” Foxglove said.

“It’s a city,” Trillium said. “Or, it was a city.”

“It’s a well-fed, smelly, rich man.”

“How can anyone be well-fed?” Coral said.

“Trust me. This man can.” Foxglove flipped her hair back and slid up on the table, exposing the slow curve of her stomach. The tattoo there read Charleston, sloped to follow her hip.

Coral hadn’t seen all of Foxglove’s tattoos, though she could have. Anyone could have, for a price. Foxglove danced at the club at the edge of the junkyard. Its sign glowed pink, day and night, pulsing with a light you couldn’t buy or make anymore, a color that always burned. Mr. Fall said the glow was called neon.

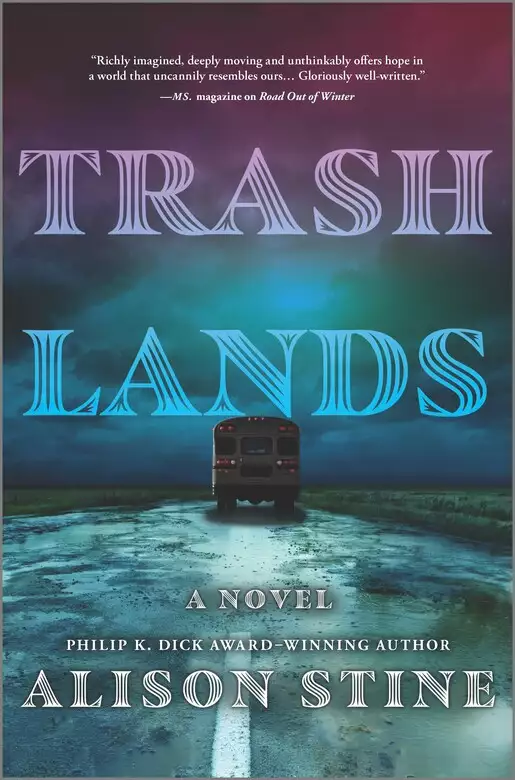

The club was called Trashlands.

So was the junkyard surrounding the club where they lived. She was sure Rattlesnake Master, the man who had started the club, fixing up an old theater, and made the path leading straight there, liked it that way: he had named all he could see.

Coral had met Foxglove years ago when the dancer had wandered up to the bus with money in her hand. Foxglove had worn shoes made from small wooden boxes, lashed to her feet with ribbons that had once been pink. Her toenails, exposed in the shoes, were red. At first, Coral had thought her feet were bleeding. The box soles lifted her taller than the man who stood behind her, kicking at a bit of plastic on the ground. The scruff of a beard made his face look dirty.

Foxglove wobbled on the shoes. She had drawn her eyebrows on shakily. Her lips were dark lines. She had a mark by her eye. Coral thought it was a birthmark or a scar. Only later, the first time Foxglove lay on Trillium’s table, did Coral see it was a tattoo. Baby. She could barely read the name.

Foxglove didn’t like to talk about that one.

Coral’s hair was red too, but not like Foxglove’s. Coral’s hair came out of her head like she imagined electricity had come out of walls: frizzed, streaked with white like lightning. Foxglove’s hair shone with the kind of glow that came from chemicals, and from not spending time outside or in the water. She was no scavenger.

Anyone else would have been laughed at, wearing the clothes Foxglove wore: a tube on top, shorts on the bottom. She would get scratched by branches in those clothes. Her bare legs would be bit. She might get an infection if she brushed a bit of metal in the yard. Her skin should have been burned and spotted, like Coral’s was. But dancing kept Foxglove out of the sun. Generators fed chilled air into Trashlands, where it was always dark, always cool, always night.

Foxglove had waved her money. It was the color of shallow water.

“We don’t accept paper money,” Trillium said. It was hard to trade it, hard to know it was real. “Plastic only.”

“Oh.” Foxglove sounded disappointed, like a child.

“We could take your shoes?” Coral said.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Trillium said. “Where would you wear them? She can’t even walk.”

“She’s not supposed to walk,” the man said.

Foxglove said nothing.

Coral tried to imagine a life where she had chemicals in her hair, where she kept out of the sun, where she stood as tall as Trillium, bending over him as he lay on their mattress stuffed with plastic ground fine as sand. Coral still remembered sand. She still remembered Robert’s face in the icehouse, the hush of his breath, as if it hurt to even look at her. Trillium used to look at her like that; he used to speak to her softly. Could high box shoes help him do that again? Would Coral look different, sexy? Would Trillium see her differently?

Foxglove turned to the man behind her. “What else you got, Polar?”

Polar, whose full name was Polar Bear, had a lawn chair—and that, they took. In exchange, Trillium gave Foxglove a tattoo.

Polar Bear had watched when Trillium worked on the dancer. Some of the men did. That was part of it, not only owning Foxglove, possessing at least a part of her body, the part that bore their name—but also watching her suffer through pain, watching her bleed for them. They liked it when she cried out. She didn’t need to—she told Coral later she could take great physical pain, had grown a kind of armor against it—but she did it for the men. Whimpers. The tiniest of tears. She was onstage even when she wasn’t.

The man called Hague hadn’t watched. He wasn’t even in the bus.

“He said he’s squeamish,” Foxglove said, turning her head to see the new tattoo in the mirror Trillium produced.

“Squeamish and well-fed?” Coral said. “Must be nice.”

“He isn’t. Nice.”

“Where does Rattlesnake Master keep finding these men?” Trillium muttered. He stood behind Foxglove, holding the mirror.

“He advertises. The cool air is a big draw. Plus, he has those little shows sometimes, you know.” Foxglove twisted to find the right angle. Coral wondered for a moment if this was how she moved onstage, if this was what the men paid for. Coral had never seen a show or been in the front part of Trashlands. It remained a mystery to her, behind a velvet curtain. Foxglove reached for her shirt. “The tattoo looks great. He’ll love it.”

“Anytime.” Trillium put the mirror down, stripped off his patched gloves into a bucket, and washed his hands with the jug in the sink.

Coral watched the water closely. They were getting low.

Foxglove pulled her shirt back on. She had been at Trashlands since she was a child, but all of life was work, really. Children were just the ones who did the small work, the nimble-fingered labor.

Coral tried not to think of him. Her son was older now. He had never been in the kind of danger Foxglove had been in. And even she wasn’t in danger anymore. Not as much, anyway, Coral hoped. Foxglove could take care of herself, keep her tips. She had a trailer in the junkyard, and years ago, Rattlesnake Master had hired a bodyguard to watch over her.

Foxglove was younger than Coral. Not a single line on her. Not a scar she had not been paid for. Sometimes Coral worried about Trillium alone in the bus with the girl, her body unrolling like a beach. But he had promised. He had sworn an oath to Coral, long ago. They were as good as married.

Foxglove reached into her blue Walmart bag, and pulled out a naked plastic doll. She handed it to Trillium, feet first. Its hair stuck up like dead grass. “Is that enough? I wish it were more.”

Trillium took it. The plastic would be melted. Children didn’t play with plastic toys, not whole ones. “It’s fine.”

Foxglove turned to Coral, and her eyes in their outlines of ash looked so kind, Coral reminded herself she did not have to worry about the dancer being alone with Trillium. Foxglove wouldn’t hurt her like that, either. “How close are you to getting your son back?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved