EQUALLY TROUBLED AND TROUBLESOME, GIORGIO DE MARIA(1924–2009) was undoubtedly one of Italy’s most eccentric, imaginative, and downright unlikely weird fiction authors. If nothing else, his novels have a special talent for ambushing the reader. No matter how cosily his scenes begin, no matter how goofy or bland everything seems on the surface, a panic attack is always lurking in wait. A typical De Maria story mixes the campy with the traumatic, the winsome with the menacing. But there’s no safety in its campiness—nor should we expect any. Throughout his career, De Maria was disturbed and intrigued by terrorist violence (an obsession that became all too relevant in the 1970s as Italy plunged into political bloodshed during its “Years of Lead”). And it bears saying that terror attacks seldom happen in dark, foreboding places. It’s the brightly lit, bustling, cheerful parts of a city that invite atrocities. Complacency and terror are secret allies, and this holds as much when the terror is paranormal.

A great admirer of Kafka and Robert Louis Stevenson (and a closet reader of assorted sci-fi) De Maria nevertheless occupied an awkward position in Italian letters. His works—which boast such oddities as avant-garde psychosurgery, telepathic terrorism, phantoms, murderous statues and counterfactual histories of the Soviet Union—were never referred to as “sci-fi” or “weird fiction” in his lifetime. De Maria’s milieu was the world of Italian literary fiction, and he made little effort to “cross over” into the realm of genre publishing and fandom. None of his fiction, however fantastic, was ever released by magazines or publishers specializing in SF/F, while his champions in the world of literary fiction found him hard to categorize, a square peg hovering between a round hole and a triangular one.

For all this, De Maria made his loyalties to the fantastic clear. In an April 1978 interview for the magazine Sipario, he stated:

Unfortunately, Italian literature has a very weak tradition as far as the fantastic genre goes; our reading public is limited to viewing foreign models when it wants to immerse itself in a different dimension from what our literati offer it. Still, I think that the dimension of the fantastic, as much as this may seem paradoxical, is the most fitting one to express a reality as complex as ours today, by its ability to achieve a synthesis through metaphor. This is what realism cannot do.

De Maria’s unusual literary career occupied a twenty-year period of his life, bookended by two crises. During his youth in the 1950s, he was a dextrous and talented pianist, with classical training from Turin’s Conservatorio. At his home, he hosted salons for a close circle of intellectual friends, composing witty (and bitingly sacrilegious) piano songs in reaction to his strict Catholic upbringing. Meanwhile, he worked in the offices of FIAT, the carmaker whose headquarters in Turin had earned the city its questionable label as “the Detroit of Italy.”

De Maria’s personality was, alas, a poor fit for the white-collar world, and—with an unemployability to rival John Kennedy Toole’s—he would be fired from various day jobs throughout his life. His first marriage, to the daughter of a top FIAT executive, likewise ended in disaster. Music was his main calling, and—before the late rediscovery of his novels—he was best remembered as a songwriter in the avant garde folk band Cantacronache (1957–1963), whose other contributors included Umberto Eco and Italo Calvino.

The start of the 1960s brought tragedy. De Maria developed a permanent cramp in one hand that made piano playing impossible. Its cause was never found, and De Maria’s children remain unsure whether it was psychosomatic or wholly organic. Losing his musical ability caused De Maria lifelong pain, and he spent much of his time in front of a piano hopelessly struggling to play with his disabled hand.

He redirected his frustration into a second career in fiction. Before his illness, he had already seen a story, “The End of Everydayism” (1958), published in Il Caffè, a post-war literary journal that functioned as an Italian equivalent to The Paris Review. Throughout the 1960s, De Maria contributed several more fiction pieces to Il Caffè, including “General Trebisonda” (1964) and an eerie story imagining the aftermath of Homer’s Iliad titled “Silence Over Troy” [Silenzio su Troia] (1962). He would re-use the latter work as the epilogue to his first novel, The Transgressionists.

These two early stories show the emergence of De Maria’s disquieting vision. In both of them, a solitary character navigates a desolate setting (the ruins of Troy, an abandoned fortress), staves off loneliness by conversing with sinister imaginary friends, and finally experiences an ambiguous disintegration of himself and the reality around him. In “Silence Over Troy,” the protagonist’s imaginary friends are revealed to be predatory phantoms who engulf him when he fails to resist their camaraderie. (The same entities feature in The Transgressionists, which appears to share a common universe with this earlier tale.) By coincidence, “Silence Over Troy” and “General Trebisonda” were published in the same period as J. G. Ballard’s collection, The Terminal Beach (1964), whose title story has a remarkably similar premise: a lone figure stranded on an island ravaged by nuclear tests who abandons the sanity of his former life and embraces the wasteland as his new home. It is unlikely, however, that De Maria was familiar with Ballard’s work at the time; he did not read English and The Terminal Beach was only translated into Italian in 1978.

De Maria had the mixed fortune to live in Turin, a city whose contradictory character forms the soul of his fiction. In the decades after the Second World War, Turin distinguished itself as a bastion of high modernist sensibility, of manufacturing, engineering, and world’s fair techno-utopianism. Its rapidly swelling blue-collar population (by the late 1960s, FIAT alone employed roughly 100,000 factory workers in Turin, drawn from all over Italy) also made it a hotbed of left-wing radicalism, competing labor movements, and mass strikes against substandard living conditions. Contrasting strangely with this rapid industrialization was the middle- and upper-class refinement of the old Turin. Bred in a cityscape of baroque royal palaces, the archetypal Turinese native is haughty, honor-bound, cagey, and dignified. But our English phrase “stiff upper lip” doesn’t quite capture this culture, whose repression comes with a shell of outward warmth and self-effacement.

De Maria, who was born in regional Piedmont, never quite belonged to the world of “pure” Turinese, though he was equally unable to escape it. Unsurprisingly, then, the most spectacular examples of Turinese manners in his fiction tend to occur in his villains. These characters embody what the pop-culture wiki TV Tropes would call “Affably Evil.” The Master in The Transgressionists terrorizes citizens with “the tone of a perfect Piedmontese gentleman.” The Appeal features a trio of middlebrow persecutors who menace the protagonist with capital punishment while discussing meringue recipes and art films. The titular war criminal of “General Trebisonda” is a man whose “authority daunted others, but [whose] affection crushed them.” Even De Maria’s Stalin—ostensibly not an Italian character at all—is friendly, jocular, and approachable, though his intentions are very bad indeed. Every death threat comes with a smile.

We may contrast this with the science fiction of Primo Levi, who was more comfortable with his Turinese identity and instead associated evil with external, Nazi German characters (such as a mad scientist who turns Jewish prisoners into birdlike monsters). It is up to each reader to judge which evil—Levi’s or De Maria’s—unsettles them more, and may be a question of whether one is more disturbed by body horror or psychic malaise, by Cronenberg or Kubin. As it happens, Levi shared a close friend with De Maria: the writer, activist, and lawyer Emilio Jona. De Maria would later fictionalise Jona as the character of Segre the Attorney—perhaps the only “good” Turinese native in any of his fiction—in his last novel, The Twenty Days of Turin (1977).

Beneath its primness and industrial modernity, Turin holds a further paradox. One of its Italian nicknames is “the City of Black Magic” and its outwardly respectable citizens have a famed penchant for seances, Black Masses, heavy metal, and secret societies. (A notorious example of the latter was the P2 masonic lodge, whose membership boasted a who’s who of industrialists and top politicians, despite the taboo status of Freemasonry in a Catholic country.) This side of Turin was especially active during De Maria’s lifetime, when the city boasted several extravagant occultists.

Among these, the most iconic was Gustavo Rol (1903–1994). Employed, at least on the surface, as an antiques dealer, Rol built a cult following by displaying astonishing abilities which were either genuinely supernatural or masterpieces of illusion that took at least as much genius as actual sorcery. His large circle of friends claimed to have seen him teleport across rooms, alter the flow of time, diagnose hidden illnesses, make statuettes come to life, appear in multiple cities at once, read minds, and scan the text of closed books. Rol professed to have gained these powers after discovering “a terrible law that links the color green, the musical fifth and heat.” According to one anecdote, Rol intimidated Benito Mussolini—at the height of his power—by predicting that he would die in 1945. Another anecdote has it that Rol helped his friend, the director Federico Fellini, to research his 1976 film, Fellini’s Casanova, by summoning the historical Casanova’s ghost for an interview. In classic Turinese style, Rol was coy about his powers and played himself down as “an ordinary man” whose abilities would soon be available to all of humanity. Alas, no successor has emerged since his death and his feats seem as inimitable now as they ever were.

Post-war Turin was also home to Lorenzo Alessandri, a surrealist painter and occultist who gained a reputation as the “Black Pope” of the city’s Satanist subculture. Alessandri’s art favored lurid, phantasmagorical subjects. A disembodied penis-monster sulking before a barren landscape… A transgender Mona Lisa stripping for a barroom of anthropomorphic sows… Flying spermatozoa in lava lamp colors… Small demonic creatures resembling X-rated Pokémon… A fetus riding a skeleton and using its umbilical cord as a whip… A grim reaper taking babies for dog-walks in front of a shop advertising “Criminal Abortions”… And, in one of his “autobiographical” moments, a painting of himself dancing naked in a Black Mass around a circle of decapitated chickens.

Alessandri, like Rol, spoke demurely of himself. To reporters, he claimed to be a regular practicing Catholic and dismissed rumours about Turinese Satanism as gross exaggerations—though he happily showed TV crews his collection of occult relics, including a mummified “hand of glory” sourced from the body of a witch.

De Maria’s first novel, The Transgressionists [I trasgressionisti], was published in 1968, a year of worldwide protests, civil unrest, and apocalyptic tidings. France was shaken by the massive strikes and demonstrations of May ’68. In California, Charles Manson and his followers were preparing for a racial doomsday war, apparently in the belief that they would become the last surviving white Americans and rule over a black underclass. In Germany, the future founders of the militant communist Baader-Meinhof Gang were setting fire to department stores. Over the following decade, a score of far-right and far-left militant groups would spring up across Europe and America, committing hundreds of bombings, kidnappings and assassinations. In Italy, this period became known as the “Years of Lead,” and saw a string of bombing massacres by shadowy neo-fascist groups (with now-notorious ties to the Italian security state) and almost weekly kidnappings and assassinations of public figures by the far-left Red Brigades. For all their political differences, these groups shared a certainty that they were living in the end times of capitalist liberal democracy. Cultish obedience, paranoia and power fantasies fuelled their brutal campaigns. Predictably, they won few friends among the general public. Even the Red Brigades eventually alienated the Italian working class whom they claimed to represent by killing trade union leaders. Instead of becoming the vanguard of a popular uprising, they slew their way to pariahdom.

This terrible decade was also De Maria’s most fertile period as a writer; from 1968 to 1977, he published four novels, culminating in his most acclaimed work, The Twenty Days of Turin.

The cost of that creativity was a mental breakdown. At the dawn of the 1980s, De Maria—until then, a belligerent atheist—shocked his friends by suddenly converting to Catholicism. He published no more fiction from that point on and instead wrote religious essays that his acquaintances judged to be vastly inferior to his previous output. As the new millennium approached, De Maria’s behaviour became increasingly erratic and painful to his loved ones.

A 2017 biography (Il diavolo è nei dettagli) by Italian Stephen King translator and horror buff Giovanni Arduino, gives the following account of De Maria’s religious mania:

One afternoon during those years, De Maria went and found [his friend] Jona intently reading poetry by Sandro Penna, a poet characterised by a deeply introspective and nebulous paedophilia. His reaction didn’t delay in arriving by post: “You and your Sanhedrin [a council of rabbis] have condemned me for belonging to the Catholic Church. Go wipe your ass with the writings of that paederast!” Jona answered with a couple of affectionate lines, which were followed by a telegram [from De Maria]: “Never mind – I love you – big hugs.”

One can count dozens of similar episodes. De Maria’s eternal conviction that [his daughter] Corallina, running late, had been snatched and raped by phantom “godless Turks” (with her relatives and Jona’s running to save her at the point of death). His note delivered to neighbours who complained about the noise of his piano: “Man is a wolf to man. Peace and goodwill, Brothers.” His fixation on renouncing his experiences with the Cantacronache group, which he now considered shameful, through Holy Masses and confessions, up to three a day. His certainty that the infamous cramps in his left hand were a divine punishment for never having married a virgin. […] His denunciation of his relatives, who were guilty, according to him, of trying to steal his house “and turn it into a brothel.” This was resolved by the intervention of a barrister colleague of Jona’s, by a fortuitous general acquittal and, in part, by a heartfelt message from Giorgio De Maria to the judge: “When there’s extreme heat during the summer and the moon comes too close to the earth, people go mad. I hope this will excuse me, Your Honor.”

During an especially distressing episode, De Maria briefly believed that he was an angel and attempted to “fly” to Heaven. He barricaded himself in his home, raucously played on an old violin and then climbed out through the window, standing on a narrow ledge on the fourth floor. Police, firefighters, and his family gathered in the street below, begging him not to jump. De Maria ignored them, leapt, and landed with a crash on a large fire brigade trampoline, injuring his foot and a firefighter’s shoulder. In his fall, he narrowly missed a fatal collision with some tram cables beside his building.

To relieve his manic symptoms, De Maria was prescribed large doses of the sleep medication Halcion. His daughter Corallina believes that his descent into benzodiazepine addiction may have been the factor that stifled his literary talent. De Maria, however, was enamored of the prescribing psychiatrist, claiming to see a resemblance between him and his idol, Robert Louis Stevenson.

De Maria spent the last years of his life as a near-hermit, devoting himself to volunteer work. Upon his death in 2009, his parish priest penned an obituary, referring to him—understatedly—as “a troubled Christian.” A newspaper tribute in La Stampa, meanwhile, memorialized him as “reclusive and atypical.”

At the time of his death, De Maria’s fiction had been out of print for decades, known only to a few specialists in Turinese literature and a small but energetic cult of fans. This changed in February 2017 when W. W. Norton’s Liveright division published a new English edition of The Twenty Days of Turin, which I translated and introduced. At that time, I noted the forgotten novel’s uncanny appeal in our own time: it appeared to predict the darkest consequences of social media and “oversharing,” and the atmosphere of bullying, rage, isolation, and paranoia that the internet has catalyzed. On its release, it won the admiration of such authors as Jeff VanderMeer, Carmen Maria Machado and William Giraldi. In the autumn of the same year, The Twenty Days of Turinwas finally reprinted in Italy, exactly forty years after its initial release, and hailed by Arduino as “Italy’s one true cursed novel.”

The positive press that this event attracted—including favorable reviews in Italy’s three largest newspapers and numerous smaller magazines—has led to an ongoing rediscovery of De Maria as a lost Italian weird fiction master. In 2018, Carmilla Online, one of Italy’s major websites for reviews of speculative fiction, ranked him alongside Robert Aickman and Fritz Leiber as a “master [at] expressing the eruption of the irrational into reality.” In 2019, another De Maria novel, The Transgressionists, was reprinted after a half-century of obscurity.

This collection aims to continue the process of rediscovery by presenting two of De Maria’s novels in English for the first time (The Transgressionists and The Secret Death of Joseph Dzhugashvili), together with three shorter works (The Appeal, “The End of Everydayism” and “General Trebisonda”). While this is far from an exhaustive list of De Maria’s imaginary output, it is fair to say that it includes most of his major contributions to Italian weird fiction, enough for English-speaking readers to make their own verdicts about his legacy.

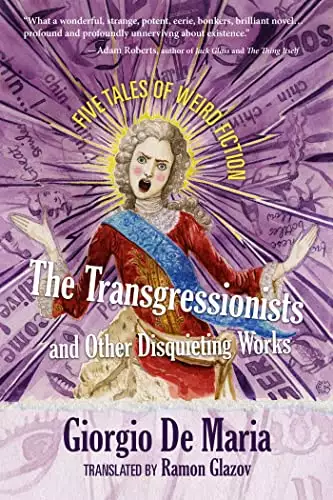

THE TRANSGRESSIONISTS

De Maria’s 1968 debut novel, The Transgressionists [I trasgressionisti], was a fitting work to herald a decade of terror, paranoia, and strife. Its unnamed antihero is a timid but covertly grandiose office worker who joins a militant cell of telepaths—the titular Transgressionists—who meet in secret to cultivate psychic powers and plot world domination.

At first, the sect shows hints of anarchistic, anti-establishment values. We wonder if this will be another 1960s counterculture story about yippies or merry pranksters resisting “the Man.” But the Transgressionists prove to be something more sinister. They are not planning a coup against the “established regime” to liberate humanity, but to rule over it as an ominous new elite. Only a chosen few who have passed a dangerous spiritual test, the “Great Leap,” will enjoy “ascendancy over the ruck of other citizens.” For those “other citizens”—their victims and future underlings—the Transgressionists show no compassion.

Perhaps to highlight the Transgressionists’ reactionary elitism, De Maria repeatedly identifies them with images of the deposed French monarchy. When the narrator first experiences the powers of the cult’s Master, a record store happens to be playing a Royal Mass by Jean-Baptiste Lully, court composer to the “Sun King,” Louis XIV. In a later chapter, the Master appears in a hallucinatory Sun King disguise to remind the Transgressionists of their “glorious” destiny. Finally, at the novel’s phantasmagorical climax, the narrator briefly finds himself before the shade of the last Dauphin of France—who has escaped the guillotine but now leads a terrible undead existence, displaced from the normal timestream. We are left to wonder if joining a psychic aristocracy is a happy fate, or the start of another soul-destroying rat race.

Despite the book’s title (and the often-uncanny feeling that De Maria had written a proto-Fight Club three decades before Chuck Palahniuk) its storytelling has surprisingly little resemblance to the scatological “transgressive fiction” of the 1990s. There is no sexual deviancy or drug use and its six chapters do not contain a single act of physical violence. All of the brutality is mental. This does not, however, make it any gentler or less psychopathic. Indeed, while The Transgressionists is no match for Palahniuk on the level of blunt force trauma or bodily excretions, it stands out in its handling of insanity. De Maria did not write in the methodical way that an American creative writing student might convey psychosis: frothy, patchy, half-Joycean but somehow familiar. His narrator’s madness often seems a little too spontaneous—too random in its mental detours and preoccupations—to be fully invented.

The novel’s Transgressionists are experts in what Killing Joke singer Jaz Coleman has aptly called “mindfucking omnipotence.” They wield the horrible power to traumatize ordinary people, unleashing shockwaves of “negative energy” that cause panic attacks in unwary bystanders or compel obedience. But their terror has an unlikely conduit. To channel their powers, Transgressionists do not use esoteric incantations, but everyday gestures, items and clichés—the blander, the better. In a memorable early scene, the eavesdropping narrator finds himself mentally devastated by nothing more than an advertising slogan for Cinzano vermouth, the toast: “CHIN-CHIN!” (By English-speaking standards, this would be equivalent to causing mass panic by uttering “FINGER LICKIN’ GOOD” in a KFC outlet, or inviting a hapless victim to “HAVE A BREAK, HAVE A KIT-KAT.”)

It may puzzle some readers how such banalities could be “triggering” to anyone. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved