- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

'Full of tension and danger... powerfully atmospheric' JENNIFER SAINT

'A beautifully crafted thriller... Breathtaking and bone-chilling' MANDA SCOTT

'Maitland is a superlative historical novelist' REBECCA MASCULL

---

Whispers haunt the walls and treachery darkens the shadows in this captivating historical novel for readers of C.J. Sansom, Andrew Taylor's Ashes of London and Kate Mosse.

Winter, 1607. A man is struck down in the grounds of Battle Abbey, Sussex. Before dawn breaks, he is dead.

Home to the Montagues, Battle has caught the paranoid eye of King James. The Catholic household is rumoured to shelter those loyal to the Pope, disguising them as servants within the abbey walls. And the last man sent to expose them was silenced before his report could reach London.

Daniel Pursglove is summoned to infiltrate Battle and find proof of treachery. He soon discovers that nearly everyone at the abbey has something to hide - for deeds far more dangerous than religious dissent. But one lone figure he senses only in the shadows, carefully concealed from the world. Could the notorious traitor Spero Pettingar finally be close at hand?

As more bodies are unearthed, Daniel determines to catch the culprit. But how do you unmask a killer when nobody is who they seem?

DANIEL PURSGLOVE BOOK TWO

---

Praise for THE DROWNED CITY

'Dark and enthralling' ANDREW TAYLOR

'This gripping thriller shows what a wonderful storyteller Maitland is' THE TIMES

'Colourful and compelling' SUNDAY TIMES

'Goes right to the heart of the Jacobean court' TRACY BORMAN

'Devilishly good' DAILY MAIL

'Spies, thieves, murderers and King James I? Brilliant' CONN IGGULDEN

'There are few authors who can bring the past to life so compellingly... Brilliant writing and more importantly, riveting reading' SIMON SCARROW

'The intrigues of Jacobean court politics simmer beneath the surface in this gripping and masterful crime novel' KATHERINE CLEMENTS

'Beautifully written with a dark heart, Maitland knows how to pull you deep into the early Jacobean period' RHIANNON WARD

(P) 2022 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: March 31, 2022

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

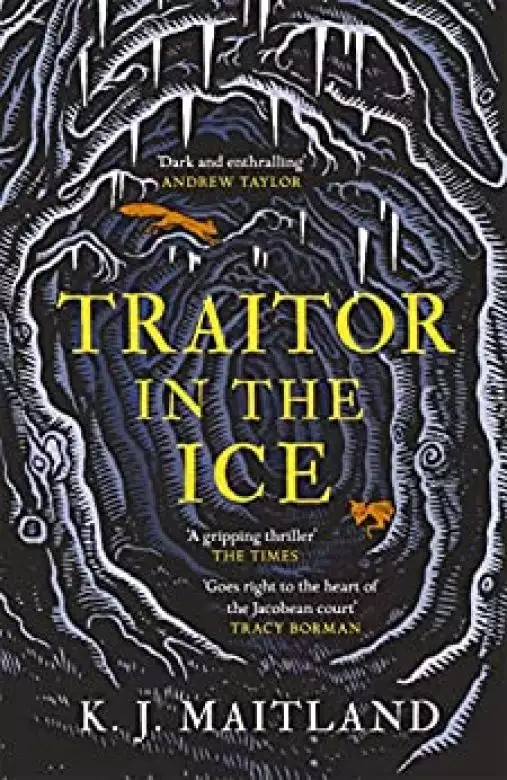

Traitor in the Ice

K.J. Maitland

Chapter One

LONDON

5TH DAY OF NOVEMBER 1607

OUT OF THE DARKNESS, cannon fire roared across the river, reverberating off the buildings around Charing Cross. Shutters and doors rattled, and an old barrel set on top of the teetering pile of firewood, towering almost as high as the Eleanor Cross itself, crashed to the ground, exploding into a shower of splinters and dust. But the crowd gathered around only roared with merriment when those close by fell over their own feet as they scrambled aside. Another round of cannon fire answered the first, and the night sky was suddenly lit by a red and orange glow as bonfires all along the banks of the Thames, and in every patch of open ground in the city, burst into flames. In Charing Cross, two men dashed forward to the heap of wood, brandishing burning torches, trails of smoke and fire streaming behind them in the chill breeze. They thrust the torches deep into the base of the bonfire. The rush and crackle of flames as they swept up through the pyre was drowned out by the roar of the crowd.

‘Traitors! Traitors! Death to all traitors!’

Two small boys ran up, their arms full of broken wooden panels that looked as if they had been newly torn from the shutters of a house. Whooping, they hurled them on to the fire, their gleeful, dirty faces aglow in the flames. Judging by the assortment of wooden clothesline poles, stools and pails, many goodwives in London would be cursing the gunpowder plotters anew as their tenements and yards were ransacked for anything that passing lads could carry off to burn on the bonfires.

A man, squeezing between the houses and the back of the crowd, found himself momentarily trapped as the mass of people drew back from the stinging smoke pouring from tar-covered timbers and green wood that had been heaped on the pyre. A volley of shots rattled across the river, as men in the boats fired their pieces at the squibs exploding in the night sky, as if they were shooting at firebirds. Everyone seemed determined that this year’s celebrations should be even wilder than the last.

Church bells had been ringing out across London for most of the day, and the regular congregations had been swollen to bursting by those crowding in to listen to the thanksgiving sermons and the prayers of deliverance from the Jesuit plot two years earlier, which had threatened to blow the King, his family and every member of Parliament and the House of Lords into millions of bloody pieces. Attendance at church on this day was compulsory and few men or women, Protestant, Catholic or Puritan, would dare to absent themselves from the services when the Act of the Observance was read out from every pulpit in the land. There were eyes and spies on every street and any man’s neighbour or goodwife’s maid might be willing to report such an absence to prove their own loyalty, or for the temptation of a fat purse.

But the man trying now to extract himself from the press of people was one of the few exceptions, though you would not have guessed as much merely by observing him. He was clad in plain brown and olive-green riding clothes and leather boots. He had left his heavy riding cloak at the inn where he had taken lodgings for the night and replaced it with a short half-cloak fastened across one shoulder, which left his dagger arm free for swift defence, should it prove necessary. His dark hair, neatly cut, grazed his shoulders, but he sported no curled lovelock, and his beard, which had also been newly trimmed, was unfashionably full and long. Together with the high white collar of the shirt, they mostly concealed the scarlet firemark that encircled his neck like a noose from all but the keenest stare.

Daniel Pursglove, which was not, of course, his real name, but the most recent of many he had adopted over his thirty years, had not attended church that day, nor had he any intention of doing so. He had ridden into London late that afternoon, and now he had only two things on his mind: food, and the message he had received three days before, summoning him to the tiny hamlet of Rotherhithe on the banks of the Thames the following morning.

Obliged to spend the night in London, he had avoided the cheap taverns of Southwark; not that he had money to waste, but he had frequented those places when he had worked the streets entertaining the crowds with his tricks of legerdemain, before those same conjuring tricks had got him arrested on charges of sorcery, and he could not risk running into old friends – or enemies.

Daniel extracted himself from the crowd and started up the street away from the bonfire, but before he could turn the corner, he heard shouts and boots pounding up the street behind him. He whirled round, his back pressed against the solid wall of a house, his knife already in his hand. A dozen or so youths were running towards him, stout sticks and iron bars in their fists. Daniel braced himself, but they didn’t give him a second glance as they rushed by, slowing only when they reached some houses further ahead. The group had divided, so that they were now running along each side of the street, beating on doors and shutters with their cudgels, and gouging the plaster on the walls of the houses as they passed. A woman foolishly opened a window in one of the upper rooms, shouting at them in broad Scottish accent to ‘leave folks be’.

‘We’ll leave you be, when you leave London,’ one yelled up at her. Another started a familiar chant and the others joined in high-pitched parody of the woman’s voice:

‘Hark, hark, the dogs do bark,

The beggars have come to town,

Some in rags and some in jags

And one in a velvet gown.’

It was a dangerous mockery of King James and his Scottish courtiers, for no one in the city could mistake who the last line of the verse referred to, but it was one that Daniel had heard chanted with increasing boldness over these past months. Resentment of the Scots was growing by the day and rumours swilled through every street and village that all of the money raised by the fines on the English Catholics was being sent north of the border or lavished on the King’s Scottish favourites, the latest of which, if the broadsides were to be believed, was the dashing young horseman Robert Carr.

The woman in the upper window vanished for a moment, then reappeared with a pail, which she emptied on the men standing below. They leaped back as vegetable peelings, mutton bones and chicken guts slithered out and tumbled down. Their clothes were splashed as the soggy mess plopped into the mud, but they only laughed and jeered, scooping up handfuls of it from the street and hurling it back, splattering the walls as they tried to lob it through the open casement. The woman hastily slammed the window. The men beat on her stout front door with their iron bars, denting and splintering the wood.

They seemed hell-bent on staving it in and would probably have continued until they had succeeded, had not a young man turned into the street ahead of them. With a howl like a pack of wolves, the ‘Swaggerers’ ran at him, their cudgels and iron bars raised high. The man stared at them in a moment of frozen alarm, then turned and fled. Daniel knew if they caught him, he would be lucky if he could crawl home. Many Scots had taken up residence in Charing Cross and Holborn, banding together for protection and support from their hostile English neighbours. The Swaggerers knew their hunting grounds well and they seemed to have developed an instinct for spotting a Scot even at a distance.

A boom from the cannons rang across the city, probably from a ship making its own loyal salute to God and King. It was followed by another wild burst of shot as men fired their own pieces with reckless abandon. It was to be hoped that no one got killed this year as the ships’ crews tried to outdo each other by producing ever-louder explosions, determined to make as great a bang as the gunpowder plotters had intended.

As the sound of the cannon died away, a blast of pipe, lute, cymbals and drums rolled out from the archway ahead, with cheers and good-natured yells. The music, if you could call it that, was coming from the courtyard of a tenement inn where a play – a comedy, judging by the shrieks of laughter – had just ended. Men and women hung over the balconies tossing coins down upon the motley group of players below who, between deep bows, scrambled to scoop them up and make their escape, darting anxious glances at any new faces that appeared through the archway. Either they were not licensed to perform by the Lord Chamberlain, Daniel thought, or the play was one that might land its authors in the Tower for sedition, as the authors of Eastward Hoe had discovered to their cost. And the players had good reason to be nervous, for every informer and intelligencer in the pay of Robert Cecil or the King would be abroad among the crowds this night, listening for talk of plots, unrest or treason.

Now that the play was concluded, trestle tables were being dragged forward and those who had been in the balcony were already clattering down the wooden staircases, drawn by the smell of roasting pig and crab apple sauce that wafted out tantalisingly from the kitchens. Daniel’s belly growled. But he marched on passed the inn and drew back into the recesses of a dark doorway, from where he could watch the street without being seen. Behind him, a broad shaft of light spilled out right across the road from the lanterns and torches that had been lit in the courtyard of the inn to illuminate the players. Anyone walking past would have to pass through that cone of light and would, for a few moments, be clearly visible.

Daniel had been on his guard ever since the message from Charles FitzAlan had arrived, sure that his journey into London was being tracked and that FitzAlan would already know where he was lodging and would have someone trailing his every step. But none of those who strolled through the shaft of light seemed to be following him. No one quickened their pace as if they had lost sight of their quarry or pulled hoods lower over their faces as the light struck them.

He forced himself to wait a little longer, then made his way back to the courtyard, seating himself in the corner beneath the overhang of balcony above, from where he could watch all who came and went through the archway. The pork proved to be every bit as succulent as it smelled, the skin crisp, honey-sweet and spicy, glistening red-gold in the lamplight. The musicians continued to play bawdy songs on fiddle, lute and pipe which a few customers joined in singing, but most were occupied with the serious task of eating and drinking, while others wagered on games of Maw or Hazard, their muttered conversations punctuated by shouts of triumph or groans as they won or lost on the roll of the dice or the card in their hands.

The inn was evidently a popular one, especially on this night when every man and woman in London seemed to be abroad, determined to make the most of the revels. No table or bench remained empty for long, as those pushing out through the archway were quickly replaced by those shoving in, seduced by the savour of sweet roasting meat and the familiar tunes of the musicians. Those who could not find places to sit had gathered close to burning braziers, for though the courtyard was sheltered on three sides by the buildings, with the coming of darkness the air had taken on a sharp winter chill and a snide wind from the river made even those highborn enough to be wrapped in fur cloaks draw them tighter.

A furious yell made Daniel glance across to the far side. Two men had risen from a dicing table and now appeared to be confronting four others who had just entered the courtyard. Both the men who’d been gambling were clearly of some wealth, if not standing. Their hair was long and curled over stiff lace ruffs, plumes were fastened to their hats by jewelled broches, and by the weighty hang of their velvet cloaks, they were fur-lined. The shorter of the two men sported a long drop earing in his left ear, which gleamed red like a clot of fresh blood in the lamplight, swinging and dancing with the smallest movement of his head.

The four men who’d entered were more plainly clad, their hair shorter, their beards spade-cut, and wore long collars of soft linen in place of stiffened ruffs. As they advanced, they flicked back their woollen cloaks, three of them revealing long daggers on their belts, the other a wickedly slender stiletto, the assassin’s weapon. Although they had not drawn their blades, the threatening gestures were unmistakable. Customers began to back away. Those who had been playing with the two men swept up their dice and coins, and rapidly vacated the benches. Those seated at nearby tables also scrambled up, some slipping out through the archway, others lingering to watch. The innkeeper, alerted, perhaps, by one of the serving girls, came hurrying across the yard, frantically signalling to the musicians to play louder, as if the music might sooth the inflamed tempers. But though it drowned out the words, it was evident to all it had not calmed the men, for judging by the obscene and threatening gestures, taunts and insults were flying freely on the chill wind. All the time, the two parties were edging closer to each other.

One of the four newcomers lunged towards the pair, grabbing the earing that had been winking and flashing so provocatively in the light and tearing it from the man’s lobe, ripping the flesh away with it. The man yelped, pressing his hand to the wound. Blood ran from between his ringed fingers, splashing down on to the white lace ruff. The musicians’ notes faltered and died as they retreated. The assailant brandished the jewel aloft in a clenched fist, whooping in triumph and punching the night sky with it, while his three companions rocked with exaggerated guffaws of laughter.

‘Whoreson Scots!’ a man close to Daniel snarled. ‘Been snatching earrings all over London. Some’ve had their whole ear slashed off.’

‘Aye.’ His neighbour shook his head ‘So, you’d think those popinjays would have more brains than to walk around wearing them if they’re not looking for trouble.’

‘And why should any true Englishman be forced to change what he wears in his own city by those foreign barbarians?’ his wife retorted.

Her husband opened his mouth to argue but was cut off by a screech of rage. All craned to see what was happening. One of the serving girls came flying out from the kitchens like an avenging fury, yelling curses at the Scots. She pulled the wounded man down on to a bench, cradling his head against her breasts, and attempted to staunch the copious flow of blood with the stained and grubby cloth she used to wipe the spills from the table.

His companion unfastened his cloak clasp with one hand as he drew his rapier with the other. The cloak fell to ground and he advanced on the Scotsman, who had his back to him and was still waving his prize aloft, jeering and laughing. His fellow countrymen, catching sight of the weapon, yelled a warning and pulled out their own daggers. The ringleader whirled round and tried to unsheathe his stiletto, but he was not swift enough. The rapier flashed as the Englishman thrust it forward in a deadly strike. The Scotsman swerved aside, but though it missed his heart, the blade went right through his shoulder with such force that the steel, glistening with scarlet blood, protruded a good three or four inches out the other side. The Englishman twisted it, trying to drag it out, while the Scot, his face contorted in agony, kicked out at his stomach, attempting to knock him backwards and wrench the weapon from his hand. After a moment’s hesitation, the other three Scotsmen darted into the fray, their daggers drawn, while another man vaulted across a table and savagely struck the Englishman’s sword arm with an iron ladle, so that he lost his grip on the rapier hilt. But the crowd around were not standing for that. Brandishing stools, knives and even wooden trenchers, men and women alike charged at the Scots.

For a moment, little could be seen or heard except for shrieks and yells, the crash of overturning benches, and the clatter of falling pots and jugs as the knot of people pushed and shoved. Then, with a howl of fury, the gang of Swaggerers that Daniel had seen earlier came running into the courtyard. At the sight of them, two of the Scotsmen tore themselves free from the fight and, unable to escape through the archway, charged towards the doorway of the inn, slashing out wildly with their daggers as they ran. The man who had snatched the earring staggered after them. He had evidently managed to wrench the rapier from his shoulder, but blood was streaming down his arm, leaving a wet glistening trail on the flagstones behind him. The fourth man lay slumped on the ground, his face battered and bleeding. The Swaggerers charged after the fleeing men. The Englishman, pausing only to snatch up his rapier, sprinted after them. As they hurtled towards the parlour door of the inn, they came within touching distance of Daniel.

Up to then, the face of the man wielding the rapier had been largely in the shadows, but now Daniel saw him clearly. He was in his thirties, tawny blond hair, his cheeks clean-shaven and a beard trimmed into a short, sharp point. Those eyes, pale and green as spring grass, were only too familiar to Daniel. In fact, he knew them better than he knew his own, for he’d spent most of the first fifteen years of his life studying, sleeping and eating in this man’s company. Together, they had learned to ride, to duel, to fight. Together they had grown from boys to men. They had been raised as if they were brothers, but they were not and never could be. Richard Fairfax!

He had already reached the door, charging straight past Daniel, so intent on hunting down his quarry that he hadn’t even looked in his direction, still dismissing all those around him as not even worthy of a glance. Daniel’s dagger was in his hand before he was even aware of it, the blade pointing straight between those shoulder blades framed in the doorway. One swift thrust, that was all it would take. He had done it before. Killing a man was easy; forcing himself to lower the dagger was not. Daniel pressed himself back into the shadows, as more men crowded through the open doorway behind Richard. Then he turned and walked out through the archway, his fist still gripping the knife.

Chapter Two

ROTHERHITHE, NEAR LONDON

CHARLES FITZALAN was already seated in a high-backed wooden chair at the far end of the long narrow galley, his twisted foot hidden beneath a draped table. Daniel bowed low as the door was closed softly behind him and he waited, listening to the sound of the servant’s heavy footsteps retreating down the wooden stairs behind it. FitzAlan flicked his hand, gesturing for Daniel to come closer. Woven-reed mats stretching the length of the gallery deadened the sound of Daniel’s riding boots on the boards as he took that slow, silent walk, but he found himself acutely conscious of the empty dagger sheath swinging against his hip. The burly servant had demanded he surrender the blade down in the hall below. He had expected as much. You did not enter this man’s presence armed. All the same, he felt naked and defenceless.

The oak-panelled gallery to which he had been conducted was on the second floor of the house and ran the full length of the wing. The outer wall was blind, but from the casements on the inner wall you could look down into an enclosed knot garden below and beyond it to the slug-grey waters of the Thames. The oriel windows had been designed to make it impossible for anyone walking on the paths below to glimpse the occupants of the gallery, unless they were standing directly in one of the casement alcoves above. But it scarcely mattered on that leaden November afternoon: the garden was deserted save for a blackbird pecking at the sodden earth beneath the stark skeletons of the rosebushes.

The family who owned the house was evidently absent, for Daniel had seen no signs of life as he was led through the hall and up the stairs except for the hulk of a servant who had admitted him. The fire in the soot-black cavernous hearth had been laid, but not lit, in spite of the winter chill. Smoke rising from the chimney would send up a signal for miles that the house was being used, and FitzAlan clearly did not intend for that to be known.

Rotherhithe, which lay between Greenwich and the city of London, was a tiny hamlet, boasting few attractions except a church and a cluster of cottages. The wherryman who had rowed him there had looked at Daniel curiously, as if wondering what business any man might have in such a piddling village. Was this the only clandestine meeting FitzAlan had attended here? Who else had he summoned to this dismal house? But at least it was a house and not a prison, which is where Daniel had last been ordered to wait upon FitzAlan’s pleasure; this time Daniel was a freeman, not a prisoner, but that could change with a single word.

FitzAlan watched him approach down the gallery in silence, his fingers restlessly plucking at the hilt of his sword, as if to remind Daniel that he was armed and Daniel was not. In front of the table, Daniel bowed again.

‘Battle Abbey, do ye know it?’ FitzAlan demanded in his thick Scots accent before Daniel had even fully straightened up. ‘The late Viscount Montague’s residence, have you visited it?’ He pressed the tips of his black-rimmed fingernails together, leaning forward and studying Daniel as if he could read the answer in his face without him needing to utter a word.

‘No, sir, I have not. Though my former employer, Viscount Rowe, spoke of Anthony Montague. He was once a member of the Privy Council, I believe.’

‘Aye, he had that honour until he tried to thwart the wishes of Parliament and Queen Bess by publicly opposing the Act of Supremacy. Refused to swear the oath that the Sovereign was head of the Church of England and not the Pope. Montague should have faced the block for that treason.’ His fist clenched on the table. His tone had grown strident, but when he spoke again, his voice was brisk and light, almost as if, moments before, a demon had taken possession of him and was speaking through his mouth. ‘Are you quite certain, Master Pursglove, that you’ve not been to Battle? But you’ve been to one of Montague’s other houses, I’ve nay doubt, Cowdray Park or their London house?’ His eyes narrowed and the bulging bags beneath them seemed to flick upwards, reminding Daniel of a lizard. ‘Speak up, mon, but speak the truth. I’ll not hold against ye if you tell me the Viscount or his widow, Magdalen, called on Lord Fairfax when you were a boy. I know these recusants cleave to each other like flies to shit. There’s no blame would attach to you.’

Daniel kept his expression blank. So, you have finally admitted to knowing I was raised by Lord Fairfax. And you would most certainly hold it against me if you thought I was one of those flies.I know who you are, FitzAlan. And I know only too well the fate that awaits those you blame.

‘I do not recall ever meeting the Viscount or his wife, sir.’

FitzAlan gave a mirthless bark. ‘Lord Salisbury would say that sounds like a Jesuit equivocation, but I’ll take your words as plainly meant. After all, if you’re deceiving me and Magdalen recognises you, you’ll be paying for it with a knife in your ribs. The last man the King sent to Battle to gather evidence against her is dead, mouldering in a roadside grave. And she’d not hesitate to have another dug for you alongside him. She may be in her seventieth year, but the wits and cunning that have kept her from the block these past decades are still sharper than an executioner’s axe.’

‘Am I to meet the lady, then?’

‘Meet?’ FitzAlan gave another bark. ‘Who do you think you are, upstart!’ You may once have moved in those circles as Secretary to Viscount Rowe, but I doubt the lady in question has ever bandied words with a common trickster.’

Beneath his short cloak, Daniel’s fists clenched,

‘I don’t doubt you heard your master Rowe speak of “Little Rome”. It’s what they call Magdalen’s household at Court. Half the locals in Battle town attend Mass in that old besom’s chapel, along with all the recusant nobles in Sussex and beyond. They say as many as a hundred and twenty people have gathered there at some services, in brazen defiance of the law. The King has it on good report that there is even a holy well in Battle Abbey grounds to which she and other women make regular pilgrimage. That old woman’s houses are crammed to the rafters with retired Marion priests, whom she now passes off as her servants. All of them lawfully ordained in England before Elizabeth took the throne, or so the old dowager claims.’ FitzAlan threw himself back in the chair and snorted. ‘If that’s so, they must have been ordained before their beardless fathers even plucked their virgin mothers, else her entire staff would now be so old they could scarcely dress themselves, much less her table.’

Still leaning back, he stabbed a finger savagely towards Daniel. ‘Mark me well, those priests she shelters now were not ordained in this realm. They’re men who stole away to France to be trained in the ways of the Devil and now they have crept back, like rats into a barn of wheat, to make mischief and gnaw away at the very foundations of this kingdom. Battle Abbey, where Lady Magdalen has taken up permanent residence, is close to the coast, and it is certain that these priest and foreign spies are being smuggled in through Battle. The pursuivant, Richard Topcliffe, informed the King that she has even allowed a Catholic printing press to be set up in one of houses, so that their poison may be spread throughout England and beyond.’

And what method of torture did Topcliffe employ to extract that information? Daniel wondered. Starvation? Whipping? Gauntlets were said to be Topcliffe’s favoured method. Topcliffe, one of several men commissioned by the Privy Council to hunt down and arrest known Catholic priests and traitors, had even endured a brief spell in prison himself when his zeal for inflicting pain had caused the Jesuit poet Robert Southwell to die under torture. Topcliffe’s crime, though, had not been Southwell’s murder, but that Topcliffe had let him die before he talked.

‘If this much is known against Lady Magdalen . . .’ Daniel began cautiously. He paused, considering how to phrase the question. It would be dangerous to ask if a warrant for her arrest had been signed. FitzAlan had already suggested Daniel had known the Montagues as a boy. He could be baiting a trap, convinced that Daniel would try to warn her.

‘Known, yes, but knowing it seems is not sufficient proof for those beef-witted bladders who call themselves the Privy Council.’ FitzAlan brought his fist down like a hammer upon the table, the bang echoing down the long empty gallery. ‘Lady Magdalen believes herself so invincible that she openly flouts the law of the land and her liege King by refusing to attend the Protestant services. What’s more, she encourages the villagers to ape her. And those blatherskites on the Privy Council claim she is a frail old woman of delicate breeding, so they will not sentence her for recusancy.’

She must have a powerful protector on the Privy Council, Daniel thought. Old age and high rank had certainly not saved others from the Tower or the block. Did she have information that someone on the Privy Council feared she could reveal if she was questioned, information which might implicate them in treason?

‘Sir, if the Privy Council refuse to have her arrested by reason of her age and a man with Richard Topcliffe’s reputation could not uncover sufficient evidence to convince them of her guilt, then what would you have me do?’

‘Do?’ FitzAlan snapped, glaring at Daniel as if he thought he was being deliberately obtuse. ‘I thought I had made that plain enough. Master Benet, the King’s pursuivant, is dead, in all likelihood murdered as he was leaving Battle to deliver his report. You appear to have a liking for digging into murders. You uncovered the truth behind those at Bristol, even though that was not your mission. Well, then, this time it is. If Benet was silenced, then it was because he had unearthed something far more dangerous to those at the Abbey than mere recusancy. Spero Pettingar has still not been run to ground. But someone knows who he is and where he is, and Lady Magdalen sits at the very heart of the Catholic network.’

Not that spectre again. Daniel’s jaw clenched beneath his beard, but he tried to keep his expression blank. FitzAlan’s obsession with the traitor had plainly not diminished over these few months. Doubtless the accursed star that had been hovering over England all through the autumn was to thank for that.

In the days that followed Guy Fawkes’ arrest, an intelligencer had reported that on the final occasion when the gunpowder conspirators had all met together in the Mitre Tavern, there was a man among them who he knew only as Spero Pettingar. After that meeting, Pettingar disappeared as mysteriously as a gold ring vanishing from a conjurer’s magic box. Even under torture, none of the conspirators admitted to knowing his real identity, but that had only served to convince King James that Pettingar was the fifth priest involved in that Jesuit plot and the most dangerous of all of the conspirators, maybe even their ringleader.

And the King could hardly have failed to notice the bearded star with a tail of fire that had been nightly blazing over England since September. The pamphleteers had taken a malicious delight in pointing out that such stars foretold the death of kings and kingdoms, no doubt fuelling James’s fear that Pettingar would again try to murder him and that this time he would succeed.

‘You believe Pettingar is at Battle, sir?’

FitzAlan frowned, then waved his hand as if swatting away an irritating fly. ‘That foul traitor has gone to ground. He might even now be in hiding in Battle, or she may have smuggled him out to the Low Countries or to Spain. But the priests and spies she shelters swarm all over England and far beyond her shores. One of them at least must know the true identity of Pettingar and where he is. It is the King’s wish that you go to Battle Abbey and get yourself taken into her household. You were raised a Catholic; you can win their confidence.’

Did this man have any idea what he was demanding? Did he imagine you could simply stroll up to the door, announce that you were a Catholic and be gathered in like a lost lamb? He was expecting Daniel to inveigle his way into this household, which half the pursuivants and intelligencers in England had tried to infiltrate without apparent success, and start interrogating the priests in hiding there about Spero Pettingar without arousing anyone’s suspicions. FitzAlan really must believe him to be a sorcerer and magician. Besides, the last thing Daniel wanted was to find himself back in a house of priests and piety; he’d spent half his youth trying to escape that.

‘Sir, there are many recusant houses throughout England which Pettingar might have taken refuge in. Has His Majesty any reason to believe—’

‘He has every reason,’ FitzAlan snapped. ‘The dowager’s late husband, Viscount Montague, his son-in-law the Earl of Southampton and Magdalen’s own brother, were all implicated in the plot to depose their lawful queen in the Rising of the North, but Elizabeth was always too inclined to mercy where justice would have better served her, and they all contrived to escape their well-deserved punishment.’

Daniel recalled hearing talk of that rebellion among some of the older commanders when he had served as a field messenger in the Irish uprising. But the Rising of the North had been nearly forty years ago, and half the recusant nobles in England had at some time or other been accused of plotting against Elizabeth. That was not reason enough to suspect the dowager now, surely?

FitzAlan eye’s narrowed as he examined Daniel’s face. He grunted. ‘Always sceptical, eh, Master Pursglove? I suppose that’s to be expected from a man who once earned his living by convincing simpletons and gowks that gold coins can appear in empty dishes and kittens be transformed into mice with the wave of a hand. Very well, I’ll tell you something more, if it will convince you. When he was little more than a boy, the man who was to set the match to the kegs of gunpowder, the very devil-of-the-vault himself, entered the service of Magdalen’s late husband as a footman on his estate at Cowdray. Fawkes was born into a wealthy and godly Protestant family, but such was the corrupting influence of the Montagues that in the short time he was with them he was turned into the fiend who tried to foully murder the King, the Queen and hundreds of innocents in Parliament, and drag England and Scotland, both, back under the heel of the Pope. It was not only Magdalen’s late husband Fawkes served, but his grandson too, when he in turn became the second Viscount Montague, for he also took this would-be assassin into his service and fed his vile nature.’

And the second Viscount was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower for that association, Daniel remembered, but even the little ferret Robert Cecil could not find enough evidence to prove that he knew about the plot to hold him, much less put him on trial.

But Daniel was grudgingly forced to admit that if Spero Pettingar had ever existed, he could probably find no better hiding place than one of Montague’s houses. If the old dowager was hiding even a handful of priests, her houses would be riddled with priest’s holes. And those hiding places must have been very well constructed, if they not yet yielded their secrets. There was only one man whom such a family as the Montague’s would have trusted to construct those hidden chambers upon which the lives of dozens of priests depended, and that was the Jesuit hunchback Nicholas Owen who, according to the official version of his death had sliced his own guts open in the Tower rather than betray a single man. Tavern gossip had it that his belly had burst open under merciless torture while he was suspended by his wrists in iron manacles. But whatever the truth, all were agreed that Owen, whom Daniel’s old tutor Father Waldegrave had always referred to as ‘Little John’, had refused to divulge the whereabouts of even one of the scores of hiding places he had constructed throughout the length and breadth of England.

Had this house in which he was now standing been one of them, Daniel wondered, seized by the Crown in penalty of praemunire, for the owners’ refusal to take the Oath of Allegiance? If it had, the long gallery would probably even now be concealing at least one hidden chamber – a secret room behind that oak panelling, or beneath the fireplace or the stairs. Owen had always ensured that every refuge was unique, so that if the secret of one was unlocked, it could not be used to crack another. But even now, Daniel did not allow his gaze to stray to the wooden panels. Waldegrave had instilled in both him and Richard that guarding your eyes was as vital as guarding your tongue. Boys, like servants, would be watched closely by the searchers. Many a fugitive had been unwittingly betrayed and seized because a child or terrified maid had glanced towards a hiding place.

‘Sir, it will not be easy to gain admittance to Battle Abbey. They will be on their guard against any who try to infiltrate the network.’

‘They will indeed.’ FitzAlan’s tone was so cheerful, Daniel half expected to see him rubbing his hands in relish at the prospect. ‘Robert Cecil has his network of turncoats and informers who pass themselves off as priests and travel with those being smuggled into this realm. And even they have failed to penetrate that stronghold.’

‘And Benet? Was his death investigated?’

‘It was not,’ FitzAlan said. ‘He was found dead in a pit on the outskirts of Battle on the road to London. But the local coroner and jury, all of whom are, no doubt, in league with that old besom, returned a verdict of felo de se.’

Daniel grimaced. ‘Self-murder? Casting yourself into a pit doesn’t seem the most reliable way for a sane man to take his own life, even if he wished to make it appear an accident . . . unless it was a very deep pit, deep enough to smash his skull?’

‘On the contrary, the reports say it was a shallow one. I’m told that someone would be unlucky to break so much as his ankle if he jumped in, much less his neck. He was returning to London to make report, I am certain of that. Whatever he had uncovered was something so important he’d not risk committing it to the hand of a messenger.’ FitzAlan’s frown had deepened and his foot was drumming rapidly against the table leg, but he didn’t seem aware of it. ‘At least, not a messenger he sent to his King,’ he added almost under his breath.

So, he suspects a message was sent, but to whom? Robert Cecil? If he did intercept it, the King’s beagle has plainly not shared that juicy bone with his master. But if not him, then Benet may have double-crossed them both.

FitzAlan suddenly jerked from his revery with a shake of his head, as if he was trying to banish the lingering image of a bad dream. ‘You must learn the truth about Benet’s death, Master Pursglove, discover what secret he had unearthed. But you’ll have to be on your guard, my wee sparrow. Outfox the old vixen and those vulpes that surround her. The fox and the Devil share the same nature. The fox besmirches himself in blood-red mud, then lays still upon the ground, feigning death until the foolish carrion crow comes ambling close, thinking it has found itself a meal. Then it is the crow that is devoured. The Devil can fool us into thinking he is dead until we have strayed into his path. The Devil and Spero Pettingar, they are neither of them vanquished, Master Pursglove. Some of the plotters ended their days on the quartering block, but they were merely the limbs of the beast; the plot was conceived in the head and the head still lives. As King Solomon himself charged his servants – “Catch us the little foxes that destroy the vines.” Catch them, Master Pursglove, and the King will see them hanged higher than vermin on a gamekeeper’s gibbet, for every crow to peck at.’

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...