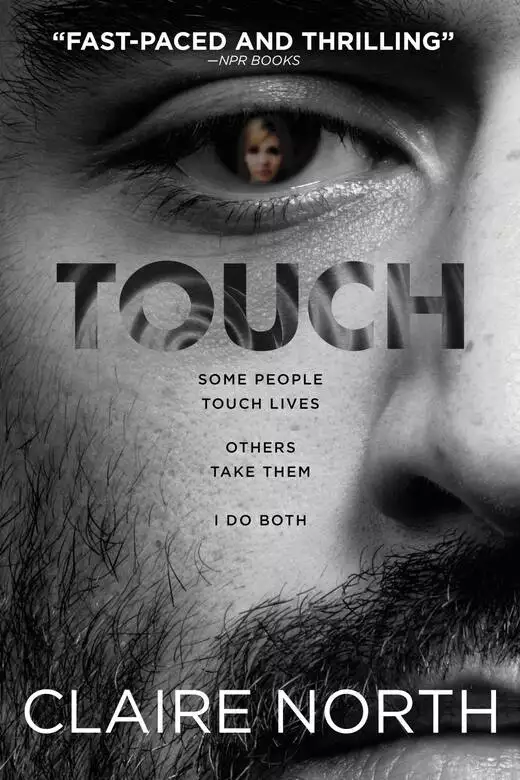

Touch

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Touch is the wildly original and masterfully suspenseful second novel from highly acclaimed author Claire North, author of The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August.

Kepler never meant to die this way—viciously beaten to death by a stinking vagrant in a dark back alley. But when reaching out to the murderer for salvation in those last dying moments, a sudden switch takes place. Now Kepler is looking out through the eyes of the killer himself, staring down at her own broken and ruined body lying in the dirt of the alley.

Instead of dying, Kepler has gained the ability to roam from one body to another—to jump into another person’s skin, see through his or her eyes, and live his or her life—be it for a few minutes, a few months, or a lifetime.

Kepler means these host bodies no harm; she even comes to cherish them intimately like lovers. But when one host, Josephine Cebula, is brutally assassinated, Kepler embarks on a mission to seek the truth—and avenge Josephine’s death.

Release date: February 24, 2015

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Touch

Claire North

She had two bullets in the chest, one in the leg, and that should have been the end of it, should have been enough, but the gunman had stepped over her expiring form and was looking for me.

For me.

I cowered in the body of a woman with swollen ankles and soft flabby wrists, and watched Josephine die. Her lips were blue, her skin was white, the blood came out of the lower gunshot to her stomach with the inevitability of an oil spill. As she exhaled, pink foam bubbled across her teeth, blood filling her lungs. He–her killer–was already moving on, head turning, gun raised, looking for the switch, the jump, the connection, the skin, but the station was a shoal of sardines breaking before a shark. I scattered with the crowd, stumbling in my impractical shoes, and tripped, and fell. My hand connected with the leg of a bearded man, brown-trousered and grey-haired, who perhaps, in another place, bounced spoilt grandchildren happily upon his knee. His face was distended with panic, and now he ran, knocking strangers aside with his elbows and fists, though he was doubtless a good man.

In such times you work with what you have, and he would do.

My fingers closed round his ankle, and I

jumped

slipping into his skin without a sound.

A moment of uncertainty. I had been woman; now I was man, old and frightened. But my legs were strong, and my lungs were deep, and if I had doubted either I wouldn’t have made the move. Behind me, the woman with swollen ankles cried out. The gunman turned, weapon raised.

What does he see?

A woman fallen on the stairs, a kindly old man helping her up. I wear the white cap of the hajj, I think I must love my family, and there is a kindness in the corner of my eye that terror cannot erase. I pulled the woman to her feet, dragged her towards the exit, and the killer saw only my body, not me, and turned away.

The woman, who a second ago I had been, shook away enough of her confusion to look up into my stranger’s face. Who was I? How did I come to be helping her? She had no answer, and finding only fear, gave a howl of she-wolf terror and pulled away, scratching at my chin. Breaking free, she ran.

Above, in the square portal of light at the top of the stairs: police, daylight, salvation.

Behind: a man with a gun, dark brown hair and synthetic black jacket, who wasn’t running, wasn’t firing, but was looking, looking for the skin.

On the stairs, Josephine’s spreading blood.

The blood in her throat sounded like popping candy when she breathed, barely audible over the racket of the station.

My body wanted to run, thin walls of an ageing heart pumping fast against a bony chest. Josephine’s eyes met mine, but she didn’t see me there.

I turned. Went back to her. Knelt at her side, pressed her hand over the wound nearest her heart, and whispered, “You’ll be OK. You’ll be all right.”

A train was approaching through the tunnel; I marvelled that no one had stopped the line. Then again the first shot had been fired not thirty seconds ago, and it would take almost as long to explain it as to live it.

“You’ll be OK,” I lied to Josephine, whispering soft German in her ear. “I love you.”

Perhaps the driver of the oncoming train didn’t see the blood on the stairs, the mothers holding their children close as they cowered behind grey pillars and fluorescent vending machines. Perhaps he did see it, but like a hedgehog before a cement lorry was so bewildered by the events, he couldn’t manage an independent original thought and so, training overriding initiative, he slowed down.

Faced with sirens above and a train below, the man with the gun looked around the station once more, did not see what he wanted, turned and ran.

The train doors opened, and he climbed on board.

Josephine Cebula was dead.

I followed her killer on to the train.

Three and a half months before she died, a stranger’s hand pressing on hers, Josephine Cebula said, “It’s fifty euros for the hour.”

I was sitting on the end of the hotel bed, remembering why I didn’t like Frankfurt. A few beautiful streets had been restored after the war by a mayor with a sense of undefeated civic pride, but time had moved too fast, the needs of the city too great, and so a bare quarter-mile of Germanic kitsch had been rebuilt, celebrating a lost culture, a fairy-tale history. The rest was pure 1950s tedium, built in straight lines by men too busy to think of anything better.

Now grey concrete executives sat within grey concrete walls, quite possibly discussing concrete, there not being much else in Frankfurt to get enthused about. They drank some of the least good beer Germany had to offer, in some of the dullest bars in Western Europe, rode buses that came on time, paid three times the going rate for a cab out to the airport, were weary when they came, and glad when they departed.

And within all this was Josephine Cebula, who said, “Fifty euros. Not negotiable.”

I said, “How old are you?”

“Nineteen.”

“How old are you really, Josephine?”

“How old do you want me to be?”

I added up her dress, which was in its own way expensive, in that so little fabric worn on purpose could only be the consequence of high fashion. A zip ran down one side, tight against her ribs and the curve of her belly. Her boots were tight around her calves, forcing them to bulge uncomfortably just below the knee. The heel was too high for good balance, which showed in her uneasy posture. I mentally stripped her of these poor choices, pulled her chin up high, washed the cheap dye from her hair and concluded that she was beautiful.

“What’s your cut?” I asked.

“Why?”

“Your accent isn’t German. Polish?”

“Why so many questions?”

“Answer them and three hundred euros are yours, right now.”

“Show me.”

I laid out the money, a note at a time, in clean fifty bills on the floor between us.

“I get forty per cent.”

“You’re on a bad deal.”

“Are you a cop?”

“No.”

“A priest?”

“Far from.”

She wanted to look at the money, wondered how much more I held, but managed to keep her eyes on me. “Then what?”

I considered. “A traveller,” I said at last. “Looking for a change of scenery. Your arms–needle marks?”

“No. I gave blood.”

A lie, one I didn’t need to call her on, it was so weak in both conception and delivery. “May I see?”

Her eyes flickered to the money on the floor. She held out her arms. I examined the bruise in the nook of her elbow, felt the skin, so thin I was amazed my touch didn’t dent it, saw no sign of more extensive needle use. “I’m clean,” she murmured, her eyes now fixed on mine. “I’m clean.”

I let her hands go; she hugged her arms around her chest. “I don’t do any stupid stuff.”

“What kind of stupid stuff?”

“I don’t sit around and talk. You’re here for business; I’m here for business. So, let’s do business.”

“All right. I want your body.”

A shrug; this was nothing new. “For three hundred I can stay the night but I need to tell my guys.”

“No. Not for the night.”

“Then what? I don’t do long term.”

“Three months.”

A snort of a laugh; she’d forgotten what humour sounded like. “You’re crazy.”

“Three months,” I repeated. “Ten thousand euros upon completion of contract, a new passport, new identity, and a fresh start in any city you name.”

“And what would you want for this?”

“I said: I want your body.”

She turned her face away so that I might not spot the fear that ran down her throat. For a moment she considered, money at her feet, stranger sitting on the end of her bed. Then, “More. Tell me more, and I’ll think about it.”

I held out my hand, palm up. “Take my hand,” I said. “I’ll show you.”

That had been three months ago.

Now Josephine was dead.

Taksim station has very little to recommend it.

In the morning dull-eyed commuters bounce off each other as they ride down the Bosphorus, shirts damp from the packed people carriers that serve Yenikoy and Levent. Students bound through the Metro in punk-rock T-shirts, little skirts and bright headscarves towards the hill of Galata, the coffee shops of Beyoglu, the iPhone store and the greasy pide of Siraselviler Caddesi, where the doors never close and the lights never die behind the plate-glass windows of the clothes stores. In the evening mothers rush to collect the children two to a pram, husbands stride with briefcases bouncing, and the tourists, who never understood that this is a working city and are only really interested in the funicular, cram together and grow dizzy on the smell of shared armpit.

Such is the rhythm of a thriving city, and it being so, the presence of a murderer on the train, gun tucked away inside a black baseball jacket, head bowed and hands steady, causes not a flicker as the Metro pulls clear of Taksim station.

I am a kindly old man in a white cap; my beard is trimmed, my trousers are only slightly stained with blood where I knelt by the side of a woman who was dead. There is no sign that sixty seconds ago I ran through Taksim in fear of my life, save perhaps a protrusion in the veins on my neck and a sticky glow to my face.

Some few metres from me–very few, yet very many by the count of bodies that kept us apart–stood the man with the gun beneath his jacket, with nothing in his look to show that he had just shot a woman in cold blood. His baseball cap, pulled down over his eyes, declared devotion to Gungorenspor, a football team whose deeds were forever greater in the expectation than the act. His skin was fair, recently tanned by some southern sun and more recently learning to forget the same. Some thirty people filled the space between us, bouncing from side to side like wavelets in a cup. In a few minutes police would shut down the line to Sanayii. In a few minutes someone would see the blood on my clothes, observe the fading red footprint I left with every step.

It wasn’t too late to run.

I watched the man in the baseball cap.

He too was running, though in a very different manner. His purpose was to blend with the crowd, and indeed, hat pulled down and shoulders curled forward, he might have been any other stranger on the train, not a murderer at all.

I moved through the carriage, placing each toe carefully in the spaces between other people’s feet, a swaying game of twister played in the busy silence of strangers trying not to meet each other’s eyes.

At Osmanbey the train, rather than growing emptier, pressed in tighter with a flood of people, before pulling away. The killer stared out the window at the blackness of the tunnel, one hand grasping the bar above, one resting in his jacket, finger perhaps still pressed to the trigger of his gun. His nose had been broken, then restored, a long time ago. He was tall without being a giant, hanging his neck and slouching his shoulders to minimise the effect. He was slim without being skinny, solid without being massy, tense as a tiger, languid as a cat. A boy with a tennis racket under one arm knocked against him, and the killer’s head snapped up, fingers curling tight inside his jacket. The boy looked away.

I eased my way around a doctor on her way home, hospital badge bouncing on her chest, photo staring with grim-eyed pessimism from its plastic heart, ready to lower your expectations. The man in the baseball cap was a bare three feet away, the back of his neck flat, his hair trimmed to a dead stop above his topmost vertebrae.

The train began to decelerate, and as it did, he lifted his head again, eyes flicking around the carriage. So doing, his gaze fell on me.

A moment. First stony nothing, the stare of strangers on a train, devoid of character or soul. Then the polite smile, for I was a nice old man, my story written in my skin, and in smiling he hoped I would go away, a contact made, an instant passed. Finally his eyes traced their way to my hands, which were already rising towards his face, and his smile fell as he saw the blood of Josephine Cebula drying in great brown stripes across my fingertips, and as he opened his mouth and began to draw the gun from his shoulder holster I reached out and wrapped my fingers around the side of his neck and

switched.

A second of confusion as the bearded man with blood on his hands, standing before me, lost his balance, staggered, bounced off the boy with the tennis racket, caught his grip on the wall of the train, looked up, saw me, and as the train pulled into Sisli Mecidiyekoy, and with remarkable courage considering the circumstances, straightened up, pointed a finger into my face and called out, “Murderer! Murderer!”

I smiled politely, slipped the gun already in my hand back into its holster, and as the doors opened behind me, spun out into the throng of the station.

My body.

The usual owner, whoever he was, perhaps assumed that it was normal for shoulder blades to tense so tight against the skin. He would have had nothing else to compare his experience of having shoulders with. His peers, when asked how their shoulders felt, no doubt came up with that universal reply: normal.

I feel normal.

I feel like myself.

If I ever spoke to the murderer whose body I wore, I would be happy to inform him of the error of his perceptions.

I headed for the toilets, and out of habit walked into the ladies’.

The first few minutes are always the most awkward.

I sat behind a locked door in the men’s toilets and went through the pockets of a murderer.

I was carrying four objects. A mobile phone, switched off, a gun in a shoulder holster, five hundred lira and a rental car key. Not a toffee wrapper more.

Lack of evidence was hardly evidence itself, but there is only so much that may be said of a man who carries a gun and no wallet. The chief conclusion that may be reached is this: he is an assassin.

I am an assassin.

Sent, without a doubt, to kill me.

And yet it was Josephine who had died.

I sat and considered ways to kill my body. Poison would be easier than knives. A simple overdose of something suitably toxic, and even before the first of the pain hit I could be gone, away, a stranger watching this killer, waiting for him to die.

I thumbed the mobile phone on.

There were no numbers saved in the directory, no evidence that it was anything other than a quick purchase from a cheap stall. I made to turn it off, and it received a message.

The message read: Circe.

I considered this for a moment, then thumbed the phone off, pulled out the battery and dropped them into my pocket.

Five hundred lira and the key to a rental car. I squeezed this last in the palm of my hand, felt it bite into skin, enjoyed the notion that it might bleed. I pulled off my baseball cap and jacket and, finding the shoulder holster and gun now exposed, folded them into my bundle of rejected clothes and threw them into the nearest bin. Now in a white T-shirt and jeans, I walked out of the toilets and into the nearest clothes store, smiling at the security guard on the door. I bought a jacket, brown with two zips on the front, of which the second seemed to serve no comprehensible purpose. I also bought a grey scarf and matching woolly hat, burying my face behind them.

Three policemen stood by the great glass doors leading from the shopping mall to the Metro station.

I am an assassin.

I am a tourist.

I am no one of significance.

I ignored them as I walked by.

The Metro was shut; angry crowds gathered round the harried official, it’s an outrage, it’s a crime, do you know what you’re doing to us? A woman may be dead, but why should that be allowed to ruin our day?

I got a taxi. Cevahir is one of the few places in Istanbul where finding a cab is easy, an attitude of “I have spent extravagantly now, where’s the harm?” lending itself generously to the cabbie’s profit.

My driver, glancing at me in the mirror as we pulled into the traffic, registered satisfaction at having snared a double whammy–not merely a shopper, but a foreign shopper. He asked where to, and his heart soared when I replied Pera, hill of great hotels and generous tips from naïve travellers bewitched by the shores of the Bosphorus.

“Tourist, yes?” he asked in broken English.

“Traveller, no,” I replied in clear Turkish.

Surprise at the sound of his native language. “American?”

“Does it make a difference?”

My apathy didn’t discourage him. “I love Americans,” he explained as we crawled through red-light rush hour. “Most people hate them–so loud, so fat, so stupid–but I love them. It’s only because their masters are sinful that they commit such evils. I think it’s really good that they still want to be nice people.”

“Is that so.”

“Oh yes. I’ve met many Americans, and they’re always generous, really generous, and so eager to be friends.”

The driver talked on, an extra lira for every four hundred merry words. I let him talk, watching the tendons rise and fall in my fingers, feeling the hair on the surface of my arm, the long slope of my neck, the sharp angle where it struck jaw. My Adam’s apple rose and fell as I swallowed, the unfamiliar process fascinating after my–after Josephine’s–throat.

“I know a great restaurant near here,” my driver exclaimed as we rounded the narrow stone streets of Pera. “Good fish. You tell them I sent you, tell them I said you were a nice guy, they’ll give you a discount, no question. Yes, the owner’s my cousin, but I’m telling you–best food this side of the Horn.”

I tipped when he let me out round the corner from the hotel.

I didn’t want to stand out from the crowd.

There are only two popular municipal names in Istanbul–the Suleyman restaurant/hotel/hall and the Ataturk airport/station/ mall. A photo of the said Ataturk graces the wall behind every cash counter and credit card machine in the city, and the Sultan Suleyman Hotel, though it flew the EU flag next to the Turkish, was no exception. A great French-colonial monster of a building, where the cocktails were expensive, the sheets were crisp and every bath was a swimming pool. I had stayed before, as one person or another.

Now, locked in the safe of room 418, a passport declared that here had resided Josephina Kozel, citizen of Turkey, owner of five dresses, three skirts, eight shirts, four pairs of pyjamas, three pairs of shoes, one hairbrush, one toothbrush and, stacked carefully in vacuum-wrapped piles, ten thousand euros hard cash. It would be a happy janitor who eventually broke open that safe and reaped the reward that would now for never be the prize of Josephine Cebula, resting in peace in an unmarked police-dug grave.

I did not kill Josephine.

This body killed Josephine.

It would be easy to mutilate this flesh.

There were no police yet at the hotel. There had been no identification on Josephine’s body, but eventually they’d match the single key on its wooden bauble to the door to her room, descend with white plastic suits and clear plastic bags, and find the pretty things I’d bought to bring out the natural curves in my

in her

body, a fashionable leaving gift for when we said goodbye.

The intermediate time was mine.

I toyed with going back to the room, recovering the money stashed there–my five hundred lira was shrinking fast–but sense was against the decision. Where would I leave my present body while I borrowed the housekeeper?

Instead, I went down a concrete ramp to a car park even more universally dull in its design than the Cevahir Starbucks. I pulled the car key from my pocket and, as I wound down through the foundations of the hotel, checked windscreens and number plates for a hire number, pressed “unlock” in the vicinity of any likely-looking cars and waited for the flash of indicator lights with little hope of success.

But my murderer had been lazy.

He’d tracked me down to this hotel, and used the parking provided.

On the third floor down, a pair of yellow lights blinked at me from the front of a silver-grey Nissan, welcoming me home.

This is the car hired by the man who tried to kill me.

I opened the boot with the key from his

my

pocket, and looked inside.

Two black sports bags, one larger than the other.

The smaller contained a white shirt, a pair of black trousers, a plastic raincoat, a clean pair of underpants, two pairs of grey socks and a sponge bag. Beneath its removable plastic bottom were two thousand euros, one thousand Turkish lira, one thousand US dollars and four passports. The nationalities on the passports were German, British, Canadian and Turkish. The faces, alongside their endlessly changing names, were mine.

The second, far larger, bag contained a murder kit. A carefully packed box of little knives and vicious combat blades, rope, masking tape and stiff white cotton bandages, two pairs of handcuffs, a nine-millimetre Beretta plus three spare clips and green medical bag containing a range of chemicals from the toxic through to the sedative. What to make of the full-body Lycra suit, thick rubber gloves and hazmat helmet, I really didn’t know.

I nearly missed the fat Manila folder tucked into an inner pocket, save that a corner of it had caught in the zip and showed brown against the black interior. I opened the folder and almost immediately shut it again.

The contents would require more attention than I felt able to give for the moment.

I closed the boot, got into the car, felt the comfortable fit of the seat, checked the alignment of the mirrors, ran my hand around the glove compartment to find nothing more exciting than a road map of northern Turkey and started the engine.

I am, contrary to what may be expected of one as old as I, not in the least bit old-fashioned.

I inhabit bodies which are young, healthy, interesting, vibrant.

I play with their iWhatevers, dance with their friends, listen to their records, wear their clothes, eat from their fridges.

My life is their life, and if the fresh-faced girl I inhabit uses high-powered chemical cocktails to treat her acne, why then so do I, for she’s had longer to get used to my skin, and knows what to wear and what not, and so, in all things, I move with the times.

None of which prepares you for driving in Turkey.

The Turks aren’t bad drivers.

Indeed, an argument could be made for their being absolutely superb drivers as only split-second instinct, razor-sharp skills and relentless determination to be a winner could keep you both alive and moving on the Otoyol-3 to Edirne. It’s not that your fellow drivers are ignorant of the concept of lanes, merely that, as the city falls away behind and the low hills that hug the coast begin to push and shrug against you, the scent of open air seems to provoke some animal instinct, and the accelerator goes down, the window opens to let in the roar of passing wind and the mission becomes go, go, go!

I drive rather more sedately.

Not because I am old-fashioned.

Simply because, even at the loneliest of times on the darkest roads, I always have a passenger on board.

The single most terrifying drive of my life.

It was 1958, she had introduced herself as Peacock, and when she whispered in my ear, “You want to go somewhere quiet?” I’d said sure. That’d be nice.

Five and a half minutes later she was sitting behind the wheel of a Lincoln Baby convertible, the roof down and the wind screaming, swooping through the hills of Sacramento like an eagle in a tornado, and as I clung to the dashboard and watched sheer drops twist away beneath our wheels she screamed, “I fucking love this town!”

Had I been experiencing any sentiment other than blind terror, I might have said something witty.

“I fucking love the fucking people!” she whooped as a Chevy, heading the other way, slammed on both its brakes and its horn as we barrelled towards the lights of a tunnel.

“They’re all so fucking sweet!” she howled, pins unravelling from her curled blonde hair. “They’re all so fucking, ‘Sweetie, you’re so sweet!’ and I’m all, ‘That’s so sweet of you’ and they’re all, ‘But we can’t give you the role because you’re so sweet, sweetie’ and I’m like, ‘FUCK YOU ALL!’”

She shrieked with delight at this conclusion and, as the yellow glow of the rock-carved tunnel enveloped us in its heat, pressed harder on the accelerator.

“Fuck you all!” she screamed, engine roaring like a baited bear. “Where’s your fucking bitter, where’s your fucking bile, where’s your fucking balls, you fuckers?!”

A pair of headlights ahead and it occurred to me that she was now driving on the wrong side of the road. “Fuck you!” she roared. “Fuck you!”

The lights swerved, and she swerved with them, lining up like a jousting knight, and the headlights swerved again, wheels screeching to get out of the way, but she just turned the wheel again, face forward, eyes down, no going back, and though I rather liked the body I was in at the time (male, twenty-two, great teeth), I had absolutely no intention of dying in it, so as we lined up for the kill, I reached over, grabbed her by the bare crook of her arm and switched.

The brakes gave off a primal scream of metal tearing metal, of tortured air and shattered springs. The car spun as the back wheels locked, until finally, as gentle and inevitable as the crash of the Titanic, the side of the car slammed into the wall of the tunnel and with a great belch of yellow-white sparks we scraped our way to a standstill.

The motion knocked me forward, my head bouncing down on to the hard steering wheel. Someone had tied little knots between all the neurons in my brain, making thick bundles of uncommunicative squelch where my thoughts should have been. I lifted my head and saw that I left blood on the wheel; I pressed a peacock-blue glove against my skull and tasted salt in my mouth. By my side the very pleasant young body I had been inhabiting stirred, opened his eyes, shook like a kitten and began to perceive for himself.

Confusion became anxiety, anxiety panic, and panic, having only a choice between rage or terror, went for the latter option as he screamed, “Oh God oh God oh God who are you who the fuck are you where am I where am I oh God oh God…”

Or words to that effect.

The other car, whose intended role had been the agent of our sticky demise, had pulled itself to a stop some twenty yards from us, and now the doors were open and a man was barrelling out, red-faced and cavern-skinned. As I blinked blood from my eyes I looked up to see that this gentleman, white-collared and black-trousered as he was, carried a small silver-barrelled revolver in one hand and a police badge in the other. He was also shouting, the great roaring words of a voice which has forgotten how to speak, words of my family, my car, police commissioner, going to burn, going to fucking burn…

When I had nothing to contribute on this subject, he waved the gun at me and roared at the boy to throw him my handbag. It too, like all things to do with me, was peacock-blue, adorned with green and black sequins, and glistened like the fresh skin of a shedding snake as it tumbled through the air. The man with the gun caught it awkwardly, opened it up, looked inside, and dropped it at once with an involuntary gasp.

Now no one was shouting, only the tick-tick-tick of the car engine filling the hot gloom of the tunnel. I leaned over to see what contents could possibly have induced this blissful respite from head-pounding noise.

My fallen handbag had spilt its contents in the road. A driver’s licence which informed me that my name was, in fact, Peacock, a curse clearly bestowed upon me by parents with a limited sense of ornithological aptitude. A tube of lipstick, a sanitary towel, a set of door keys, a wallet. A small plastic bag of unknown yellowish powder. A human finger, still warm and bloody, wrapped in a white cotton handkerchief, the edges ragged where it had been sawn away from the hand.

I looked up from this to see the man with the gun staring at me with open horror on his face. “Damn,” I rasped, pulling my gloves free from my hands one long blood-blackened length of silk at a time, and holding out my bare wrists for the cuffs. “I guess you’d better arrest me.”

Problem with moving into a new body, you never quite know where it’s been.

I judged myself to be halfway to Edirne by the time the sun began to set, a hot burst lighting the tarmac rosy-pink before me. Close the window of the car for even a few minutes, and the rental smell crept back in, air freshener and chemical cleanliness. The radio broadcast a documentary on the economic consequences of the Arab Spring, followed by music about loves lost, loves won, hearts broken, hearts restored once again. Cars coming from the west had their headlights on, and before the sun could reach the horizon, black clouds swallowed it whole.

I pulled into a service station as the last of the day began to fade, between two great pools of white halogen light. The station promised fast food, petrol, games and entertainment. I bought coffee, pide and a chocolate bar containing a grand total of three raisins, sat in the window and watched. I didn’t like the face that watched back from the reflection. It looked like the face of someone without scruple.

Otoyol-3 was a busy highway at the best of times, and though the signs promised Edirne as you headed west, they could equally have offered directions to Belgrade, Budapest, Vienna. It was a road for bored truckers to whom the mighty bridge from Asia to Europe acro

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...