- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

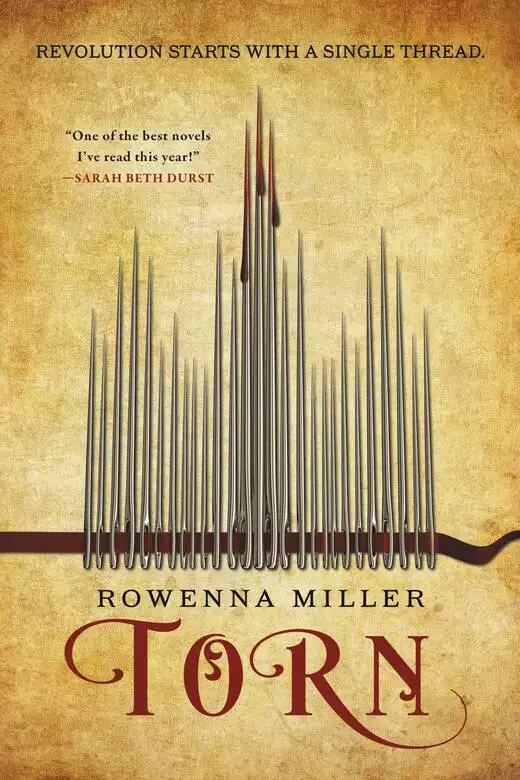

Torn is the first book in an enchanting debut fantasy series featuring a seamstress who stitches magic into clothing, and the mounting political uprising that forces her to choose between her family and her ambitions, for fans of The Queen of the Tearling.

In a time of revolution, everyone must take a side.

Sophie, a dressmaker and charm caster, has lifted her family out of poverty with a hard-won reputation for beautiful ball gowns and discreetly embroidered spells. A commission from the royal family could secure her future—and thrust her into a dangerous new world.

Revolution is brewing. As Sophie's brother, Kristos, rises to prominence in the growing anti-monarchist movement, it is only a matter of time before their fortunes collide.

When the unrest erupts into violence, she and Kristos are drawn into a deadly magical plot. Sophie is torn—between her family and her future.

Release date: March 20, 2018

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Torn

Rowenna Miller

“But, miss, I would not ask if it were—if it were not the most pressing of circumstances. If it would not be best. For all concerned.”

I understood. Mr. Bursin’s mother-in-law simply refused to die. She was old, infirm, and her mind was half-gone, but still she clung to life—and, as it turned out, bound the inheritance to her daughter and son-in-law in a legal tangle that would all go away once she was safely interred. Still.

“I do not wish ill on anyone. Ever. I sew charms, never curses.” My words were final, but I thought of another avenue. “I could, of course, wish good fortune on you, Mr. Bursin. Or your wife.”

He wavered. “Would … would a kerchief be sufficient?” He glanced at the rows of ruffled neckerchiefs lining my windows, modeled by stuffed linen busts.

“Oh, most certainly, Mr. Bursin. The ruffled style is very fashionable this season. Would you like to place the order now, or do you need to consult with your wife regarding style and fabric?”

He didn’t need to consult with his wife. She would wear the commission he bought from me, whether she liked the ruffles or not. He chose the cheapest fabric I offered—a coarser linen than was fashionable—and no decorative embroidery.

My markup for the charm still ensured a hefty sum would be leaving Mr. Bursin’s wallet and entering my cipher book.

“Add cutting another ruffled kerchief to your to-do list this morning, Penny,” I called to one of my assistants. I didn’t employ apprentices—apprentices learn one’s trade. The art of charm casting wasn’t one I could pass on to the women I hired. Several assistants had already come and gone from my shop, gaining practice draping, cutting, fitting—but never charm casting. Alice and Penny, both sixteen and as wide-eyed at the prospect of learning their trade as I had been at their age, were perhaps my most promising employees yet.

“Another?” Penny’s voice was muffled. I poked my head around the corner. She was on her back under a mannequin, hidden inside the voluminous skirts of a court gown.

“And what, pray tell, are you doing?” I stifled a laugh. Penny was a good seamstress with the potential to be a great one, but only when she resisted the impulse to cut corners.

Penny scooted out from under the gown, her pleated jacket bunching around her armpits. “Marking the hem,” she replied with a vivid crimson blush.

“Is that how I showed you to do it?” I asked, a stubborn smile forcing its way onto my face.

“No,” she replied meekly, and continued with her work.

I returned to the front of the shop. Three packages, wrapped in brown paper, awaiting delivery. One was a new riding habit with a protective cast, the second a pelisse for an old woman with a good health charm, and the third a pleated caraco jacket.

A plain, simple caraco. No magic, no spells. Just my own beautiful draping and my assistant Alice’s neat stitching.

Sometimes I wished I had earned my prominence as a dressmaker on that draping and stitching alone, but I knew my popularity had far more to do with my charms, the fact that they had a reputation for working, and my distinction as the only couture charm caster in Galitha City. Though there were other charm casters in the city, the way that I stitched charms into fashionable clothing made the foreign practice palatable to the city’s elite. The other casters, all hailing from the far-off island nation of Pellia by either birth or, like me, ancestry, etched charms into clay tablets and infused sachets of herbs with good luck or health, but I was the only charm caster in the city—the only one I knew of at all—who translated charms into lines of functional stitching and decorative embroidery.

Even among charm casters I was different, selling to Galatines, and the Galatine elite, who didn’t frequent the Pellian market or any other Pellian businesses. I had managed to infuse the practice with enough cachet and intrigue that the wealthy could forget it was a bumpkin superstition from a backwater nation. Long before I owned my shop, I had attempted charming and selling simple thread buttons on the street. Incredibly, Galatines bought them—maybe it was the lack of pungent herb scents and ugly clay pendants that marked Pellian charms, or maybe it was the appeal of wearing a charm no one could see. Maybe it was merely novelty. In either case, I had made the valuable discovery that, with some modifications, Galatines would buy charms. When I finally landed a permanent assistant’s job in a small atelier with a clientele of merchants’ wives and lesser nobility, I wheedled a few into trying a charm, and, when the charms worked, I swiftly gathered a cult following of women seeking my particular skill. After a couple of years, I had enough clients that I was able to prove myself and open my own shop. Galatines were neither particularly superstitious nor religious, but the novelty of a charm stitched into their finery captivated their interest, and I in turn had a market for my work.

“When you finish the hem, start the trim for Madame Pliny’s court gown,” I told Penny. The commission wasn’t due until spring, but the elaborate court gowns required so much work that I was starting early. It was our first court gown commission—a sign, I hoped, that we were establishing a reputation for the quality of our work as well as for the charms. “And I’m late to go file for the license already—the Lord of Coin’s offices have been open for an hour.”

“The line is going to be awful,” Alice said from the workroom. “Can’t you go tomorrow?”

“I don’t want to put it off,” I answered. The process was never sure; if I didn’t get through the line today, or if I was missing something the clerk demanded, I wanted several days to make it up.

“Fair enough,” Alice answered. “Wait—two messages came while you were with Mr. Bursin. Did you want—”

“Yes, quickly.” I tore open the two notes. One was an invoice for two bolts of linen I had bought. I set it aside. And the other—

“Damn,” I muttered. A canceled order. Mrs. Penneray, a merchant’s wife, had ordered an elaborate dinner gown that would, single-handedly, pay a week’s wages for both of my assistants. We hadn’t begun it yet, and so, per my own contract, I would have to agree to cancel it.

I glanced at our order board. We were still busy enough, but this was a major blow. Most of the orders on our slate were small charmed pieces—kerchiefs, caps. Even with my upcharge for charms, they didn’t profit us nearly as much as a gown. Early winter usually meant a lull in business, but this year was going to be worse than usual.

“Anything amiss?” Penny’s brow wrinkled in concern, and I realized that I was fretting the paper with my fingers.

“No, just a canceled order. Frankly, I didn’t care for the orange shot silk Mrs. Penneray chose anyway, did you?” I asked, wiping her order from the board with the flat of my hand. “And I really do need to go now.”

Alice’s prediction was right; the line to submit papers to the Lord of Coin was interminable. It snaked from the offices of the bureau into the corridors of the drafty stone building and into the street, where a cold rain pelted the petitioners. Puddles congregated in the low-lying areas of the flagstone floor, making the whole shabby establishment even damper and less welcoming than usual.

I held my leather portfolio under my fine wool cloak, only slightly dampened from the rain. Inside were the year’s records for my shop, invoices and payment dates, lists of inventory, dossiers on my assistants and my ability to pay them. Proof that I was a successful business and worthy of granting another year’s license. I traced my name inscribed on the front, tooled delicately into the pale calfskin by the leatherworker whose shop was four doors down from mine. I had indulged in the pretty piece after years of juggling papers bound with linen tape and mashed between layers of pasteboard. I had a feeling the ladylike, costly presentation, combined with the fashionable silk gown I wore like an advertisement of my skills and merchandise, couldn’t hurt my chances at a swift approval from the Lord of Coin’s clerk.

I was among a rare set of young women, not widows, with their own shop fronts when I opened almost ten years ago, and remained so. My business survived and even grew, if slowly, and I loved my trade—and I couldn’t complain about the profits that elevated my brother, Kristos, and me from common day laborers to a small but somewhat prosperous class of business owners.

“No pushing!” a stout voice behind me complained. I stiffened. We didn’t need any disruptions in the queue—any rowdiness and the soldiers posted around the building were likely to send us all home.

“I didn’t touch you!” another voice answered.

“Foot’s not attached to you, eh? Because how else did I get this muddy shoeprint on my leg?”

“Probably there when you hiked in from the parsnip farm or wherever you came from!”

I hazarded a look behind me. Two bareheaded men wearing poorly fitted linsey-woolsey suits jostled one another. One had the sun-leathered skin of a fisherman or dockworker; the other had the pale shock of flaxen hair common in the mountains of northeastern Galitha. Neither had seemed to think that the occasion warranted a fresh shave or a bath.

I suppressed a disapproving sigh. New petitioners, no doubt, with little hope of getting approval to open their businesses, and much more chance of disrupting everyone else. I glanced again; neither seemed to carry anything like enough paperwork to prove themselves. And their appearance—I tried not to wrinkle my nose, but they looked more like field hands than business owners. Fair or not, that wouldn’t help their cases.

Most of the line, of course, was made up of similar petitioners. Scattered among the new petitioners who were allowed, one week out of the year, to present their cases to open a business, were long-standing business owners filing their standard continuation requests. It grated me to have to wait in line, crawling at a snail’s pace toward the single clerk who represented the Lord of Coin, when I owned an established business. Business was strictly regulated in the city; careful ratios of how many storefronts per district, per trade, per capita were maintained. The nobility judged the chance of failed business a greater risk than denying a petitioner a permit. Even indulgences such as confectioners and upscale seamstresses like me were regulated, not only necessities like butchers and bakers and smiths. If I didn’t file for my annual permit this week, I could lose my shop.

As we moved forward down the corridor a few flagstones at a time, more and more dejected petitioners passed us after unsuccessful interviews with the clerk. I knew that disappointment well enough. My first proposal was rejected, and I had to wait a whole year to apply again. I took a different tack that second year, developing as much clientele as I could among minor nobility, hoping to reach the curious ears of nobles closer to the Lord of Coin and influence his decision. It worked—at least, I assumed it had, as one of the first customers when my shop opened a year later was the Lord of Coin’s wife, inquiring after a charmed cap to relieve her headaches.

The scuffle behind me escalated, more voices turning the argument into a chorus.

“Not his fault you have to wait in this damn line!” A strong voice took control of the swelling discontent and put it to words.

“Damn right!” several voices agreed, and the murmuring assents grew louder. “You don’t see no nobles queuing up to get their papers stamped.”

“Lining us up like cattle on the killing floor!” The shouting grew louder, and I could feel the press of people behind me begin to move and pulse like waves in the harbor whipped by the wind.

“No right to restrict us!” the strong voice continued. “This is madness, and I say we stand up to it!”

“You and what army?” demanded the southern petitioner who had been in the original scuffle.

“We’re an army, even if they don’t realize it yet,” he replied boldly. I edged as far away as I could. I couldn’t afford to affiliate myself, even by mere proximity, with treasonous talk. “If we all marched right up to the Lord of Coin, what could he do? If we all opened our shops without his consent, could he jail all of us?”

“Shut up before you get us all thrown out,” an older woman hissed.

I turned in time to see a punch thrown, two men finally coming to blows, but before I could see any more, the older woman jumped out of the way and the heavy reed basket swinging on her arm collided into me. I stumbled and fell into the silver-buttoned uniform of a city soldier.

I looked up as he gripped my wrist, terrified of being thrown out and barred from the building. He looked down at me.

“Miss?”

I swallowed. “I’m so sorry. I didn’t—”

“I know.” He glanced back at the rest of his company subduing what had turned into a minor riot. They had two men on the floor already; one was the towheaded man who had started the argument. “Come with me.”

“Please, I didn’t want to cause trouble. I just want to file—”

“Of course.” He loosened his grip on my wrist. “Did you think I was going to throw you out?” He laughed. “No, I have a feeling that the Lord of Coin will close the doors after this, and you’re clearly one of the only people in line who even ought to be here. I’m putting you to the front.”

I breathed relief, but it was tinged with guilt. He was right; few others had any chance at all of being granted approval, but cutting the line wouldn’t make me look good among the others waiting, as though I had bought favor. Still, I needed my license, and I wasn’t going to get it today unless I let the soldier help me. I followed him, leaving behind the beginnings of a riot truncated before it could bloom. The soldiers were already sending the lines of petitioners behind me back into the streets.

BY THE TIME I HAD MY PAPERS STAMPED AND MY LICENSE APPROVED for the following year, afternoon shadows were lengthening on the cobblestones outside the Lord of Coin’s offices. At least, I thought as I gathered my cloak more snugly around me, the rain had abated somewhat. The fine mist that replaced it still dampened my shoes, but it couldn’t penetrate the fine wool of my cloak. It was pointless to return to my shop now—I wouldn’t have time to get any work done, and Alice could lock up without me.

It wasn’t my habit to stay out after work, but after waiting in a line of strangers for hours, I had a hankering for a bowl of sausage coddle and knew where I could find it—and likely some company, too. Sure enough, my brother was already ensconced at one of the long tables by the window of the Rose and Fir tavern, with several of his comrades from the docks.

“Sophie!” Kristos grinned, half standing and waving me over. “What’s the occasion? Full moon? Lost your way home?”

“Very funny.” I tried not to smile. “You took the last of the onion pie I was saving for supper, that’s all.”

“So you came down here for some fine company.”

“I decided I could endure the company for the coddle.” I slid onto the bench next to him. Even a year ago I wouldn’t have been willing to part with a few copper coins for supper at a tavern; I hoarded anything left after rent and shop expenses in case of a bad season or an emergency and, as a result, ate meals cooked poorly over a stove designed to warm a house instead of cook or, sometimes, went without hot food at all. Kristos and his friends, and most day laborers, bought food from street stalls and taverns whose cheap wares catered to their long days and short wages. They spent little more than I did, in the end, and Kristos made fun of the penny-pinching that resulted in eating the occasional raw onion for lunch instead of a proper meal.

I still worried that a dissatisfied customer could leave me out of work for weeks, or that the whims of those with money to spend would shift away from me. I needed more security than I had. With patience and the finest quality of work, I hoped I could gain steady clients who kept returning for my draping, not solely the charms that were often onetime indulgences, and connections to the city’s elite who could give my shop more cachet. More income could mean another assistant, a larger storefront, perhaps moving closer to the square, where I could have more visibility.

“Saw the line for the licenses today,” Kristos said after a long swig of ale. “You in it?”

“Of course,” I said. Nice of him to notice—usually Kristos half forgot that I paid for our lodgings with my earnings, and all the work that my shop entailed.

“Damn long,” he added. “Don’t they grandfather you in it at some point? Make you stop performing their tricks and jumping through their hoops every year?”

I sighed—silly of me to think he might have just been interested in my day. I prepared myself for a repeat of the diatribes I’d heard in line. “No, they never do. The rules are very strict.”

“Strict for whom?” he grumbled. “No one restricts trade or enterprise for the nobility.”

“I’m well aware,” I replied. “Arguing about it doesn’t do any good, Kristos.”

Fortunately, the serving girl arrived with my stew before he could fire back, and I turned my attention to it instead of the swiftly building political debate.

As Kristos lifted his mug of ale, I noticed a thick white wrapping under his shirt cuff. I grabbed his arm, making him slosh a little ale onto the table. “What’s this?”

“Barely anything,” he said, shaking me off. “Wheelbarrow got away from me down at the docks, wrenched my wrist a little.”

“And?”

“And it will be fine in a day or two.” He ran a hand through his disheveled dark hair, further mussing waves that were in need of a good combing, clearly annoyed with me, and clearly avoiding discussing what an injury meant—lost wages.

I suppressed a sigh, not wanting to make Kristos feel bad, but a day or two for his wrist to heal likely meant a day or two he wouldn’t be working—at least. That, along with the canceled order and the start of the slow season, was not good news. I made more money than Kristos, of course, but we relied on both our incomes, especially as the additional burden of heating the house approached.

“Hey, Kristos!” My brother’s friend Jack swung a leg over the bench across from me. “You hear about what happened at the Lord of Coin’s this afternoon?”

I focused more intently on my stew.

“Porter the fishmonger—you know, he’s been trying to open a proper storefront?” There were assents murmured around me. “Went down to apply for his license and there was a bit of a row—anyway, he turned the whole thing into a protest.”

“Good on him!” A chorus of enthusiastic voices made me look up. My brother beamed. “That will show them!” he crowed. “He’s one of the cornerstones of our Laborers’ League—I’m not surprised he voiced his thoughts.”

“Show them what?” I muttered, chasing a piece of sausage with my spoon. The Laborers’ League—the ragtag coalition of day laborers Kristos met with to talk politics, as though it did any good. Kristos wasn’t content, and he made it clear to me through his participation in the League. He never had been satisfied with working unskilled, manual jobs, and I could never find it in myself to blame him. Bright, quick with a pen, and conversationally competent in Fenian and Pellian as well as Galatine, he would have been a fine university scholar had he been born to the nobility—or been my younger sibling instead of older, able to wait until I had made enough money to pay tuition.

“They had to shut the whole place down to clear out the protesters,” Jack bragged.

“You were there today, Sophie. Why didn’t you say anything?” Kristos scooted closer to me. “Seems like it would have been something to see.”

I bit my lip. “I was there for my papers. Not to cause a ruckus.”

“So you were in ahead of them? Left before it happened?” He shrugged. “Must have, or you wouldn’t have gotten your license today.”

I found I couldn’t admit I’d accepted help from the city soldier, help I earned with my silk gown and leather portfolio. “That’s right.”

Kristos sighed. “I just don’t see how you can’t care about how they treat us,” he said. “After everything you went through to open your shop. How can you see it as fair?”

“It’s not fair, exactly. It’s just … it’s how things are. And I did open my shop. Don’t forget that, Kristos. You’re railing as though it’s impossible, and it clearly isn’t.”

“And you’re forgetting the years where you barely scraped by working day-contract jobs and sweeping floors.”

“I’m not forgetting anything.” After our mother died of one of the consumptive fevers that swept the densely populated city every few years, I worked as a day laborer. As she had done and as my brother still did, I spent years finding a day’s work at a time, sewing hems for a day’s wages in one shop and sweeping floors in another the next day.

I wasn’t forgetting our slim list of orders or the onset of winter’s slow season, either. I wasn’t forgetting the fear that I would have to fire one of my assistants, or that we wouldn’t be able to afford enough coal to adequately heat our drafty workroom. Owning a shop came with responsibility that Kristos couldn’t even fathom, and it was weighing on me tonight. “What, you think everyone in the city should own a shop? How would that work?”

“It wouldn’t, and I never said—damn, Sophie. I just don’t think you should have to wait in line every year to prove you have a decent shop, or that you should have had to fight so hard to build a dossier in the first place.”

“The system isn’t perfect, but it works,” I argued lamely. “And it works for us.”

“It works for you,” Kristos replied, more bitter than I anticipated. “But—hey, Jack—there’s some good news, too.” He grabbed a thin Pellian by the elbow and dragged him toward us. “This is Niko Otni—he’s one of the river sailors who’s been coming to our meetings—”

“I remember,” said Jack, shaking his hand with earnest fervor.

“He says the barge workers and the farmhands are ready to join with the Laborers’ League,” Kristos said with a grin.

Jack did some quick calculations, his thick fingers tapping his thumb. “That could double our numbers. And the barge sailors are already pretty organized; that helps.”

Numbers—for what purpose? I didn’t want to argue, so I feigned a smile. “That sounds promising,” I said, even though the promise wasn’t one I was fond of. More late nights yelling over drinks in the café. More days wasted earning signatures on petitions instead of wages. Though Kristos assured me again and again that the aims of the League were petitions and talks and education alone, plenty of people in it had ties to the violent riots that had consumed the city in the summer. I edged away from it like a horse shies from a snake—perhaps harmless, but perhaps capable of striking and killing.

“It is. Oh, Sophie, you have no idea. If we’re going to topple the old system, we have to have the entire bottom rise up together.” He leaned heavily on the table. It creaked under his weight. “Change requires these kinds of numbers.”

I eyed him. He’d talked about change before, but never in words that sounded so much like sedition. I dreaded the wasted hours and tavern bills his League brought us, but this sounded more serious. “You’re being careful, aren’t you? You’re not wrapped up in anything … anything illegal?” He and his friends talked about elected systems of government and economics based on free enterprise instead of noble control, but that was talk. Hypotheticals fueled by the lectures some of the professors at the university had begun offering, overviews of theory and philosophy, but hardly pragmatic. Talk over pints and bottles of cheap wine. At least, I hoped it was talk—not something that Kristos could get himself arrested over. After the near riot at the Lord of Coin’s offices, I was less sure.

“Speech and press are still open in Galitha,” Kristos retorted, “even if the minds of nobles aren’t. So no, nothing illegal. Stop worrying like an old hen, Sophie.” Jack laughed at my wrinkled brow, and Niko smirked at Kristos’s joke.

I smacked his arm as though he were only teasing, but I didn’t feel playful. As Kristos resumed speaking in low tones to the men sitting on the other side of the bench, I listened more attentively than usual, fearing that their talk had turned from theoretical to intentional, from conversations and lectures to more riots and arson like the summer’s unrest.

“Porter had the right idea,” one of the other men said. I didn’t know his name, only that he was like the other day laborers, fresh from the docks or the warehouses. Perhaps he’d spent the day looking for work and coming home without a wage, as the bricklaying and building slowed in the winter.

Jack hedged his reply with a glance at me. “Maybe the right motive, but it didn’t do much good except get a bunch of folks thrown out for the day.”

“No, it sent a message,” said Kristos. “We’ve been passive so long that the nobility can forget we even exist, let alone that we are at odds with their governance.”

We? I pressed my lips together, biting back the retort that Kristos couldn’t assume everyone without a noble title automatically agreed with him and his Laborers’ League.

“They’ll need a stronger message,” Kristos continued. “What happened at the Lord of Coin today was small, spontaneous. Imagine the sentiment, but organized and bringing our numbers together.” That sounded, to me, more like a dangerous riot than a message. I couldn’t hide my dismay, and Kristos clammed up at my shocked face. “We’ve upset Mother Hen.” He laughed, but I felt the jagged frustration in his voice.

I quietly stood and stepped outside. I had learned long ago that my brother’s temper tended to flare and fade quickly, like sparks set to black powder. To my surprise, Jack followed me.

Jack wasn’t poor company, I reasoned. He was kind, and gentle despite his broad shoulders earned hauling crates at the docks. More often than not, I had seen him brokering peace when Kristos’s discussions grew too heated. “Sophie, you’re acting kind of off. Is everything all right?”

I stared down the street, letting the cold wind cool my burning cheeks. “I’m fine.”

“No, you’re not. You’re angry about Kristos riling everyone up.”

Despite myself, I laughed. “You’re right. I don’t like all this talk—I’m not against discussing theories, if you think it’s fun, or speculating on the best reforms, but this is all … it’s getting a bit serious, don’t you think?”

“It is serious, Sophie.” Jack stepped into my line of vision, his face earnest. “Change is serious. The nobles—they have to start listening to reason. We’re educated. At least, some of us—your brother is smarter than most of the lords, I’d wager. We’re not mindless rubble.” I resisted correcting him. “And things need to change.”

“That’s all I hear from Kristos, too,” I dismissed him. “Change. He can barely remember to change his linens.” Jack smiled at my joke, but I sensed that something had shifted, and the time for levity was over. My brother wasn’t the lanky man-child I still imagined him to be, but a leader of a movement that was only gaining in numbers and momentum and, it seemed, aspirations.

“I guess I just don’t understand, Sophie—why don’t you want to help us? You’re one of us.”

I swallowed. I wasn’t noble, certainly, and in the stark tiers of Galitha, that made me a common person alongside Jack. Yet, at the same time, I wasn’t quite one of them—I owned a business. Even their revolutionary talk put me at risk. “You all are going to have to change without my help. I have a business, Jack. A business I built.” No one—not my brother, not his friends—seemed to appreciate this. “My clients will stop buying charms from an active revolutionary. And for another”—I smiled at the impossibility—“if you succeed, what do I have left?”

“I know, if there’s no more nobles or rich folk in the city, you don’t have clients,” Jack supplied. “You know, I’ve thought about that.” He cleared his throat. “And, I mean, if you had—that is, if you wanted to—you could maybe not need the shop?” He reached for my hand.

I folded my hands under my cloak. “I don’t know what you’re getting at.”

“I mean that you need the shop to support yourself. And Kristos. But if you—if Kristos had his own business or a job with tenure—that means a job with a contract that keeps you—”

“I know what it means.”

“Then he could support himself. And if you had a husband who had a job like that, too …” Jack’s ears reddened so deeply that I could see it in the dim candlelight seeping through the tavern’s grimy windows.

I wanted to melt into the cobblestones. “I don’t keep my shop only because I have to. I like working. Sewing and charm casting—those a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...