- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

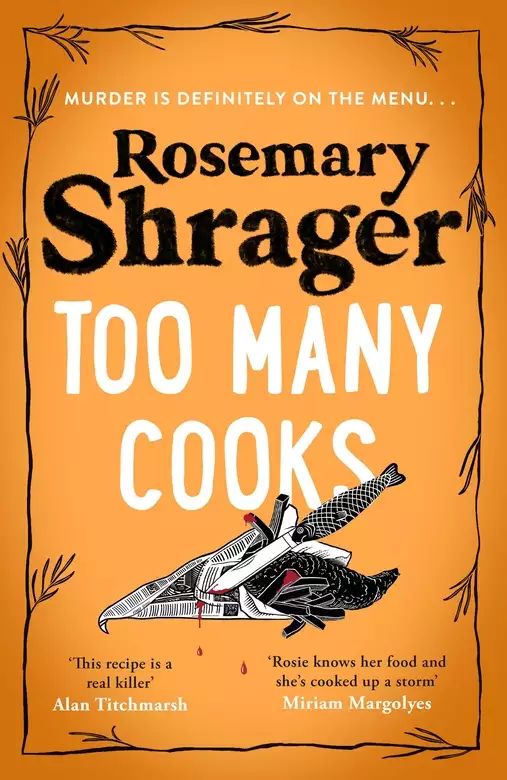

Synopsis

Prudence Bulstrode has fond memories of St Marianne's School for Girls, the beautiful Cornish school where she boarded as a girl. It was at St Marianne's that Prudence first learned the joy of cooking, from her dear old Home Economics teacher, Mrs Agatha Jubber. So when she's invited back to the school, to lead a summer holidays course in the fundamentals of cookery, Prudence couldn't be more delighted. What's more, it's a chance to show her grand-daughter Suki the way school used to be in the good old days.

But no sooner has Prudence arrived at St Marianne's, a gruesome discovery is made. The builders excavating the old hockey pitch to construct the new dormitories have unearthed human bones - bones dating from Prudence's own time at St Marianne's. Soon, Prudence recollects the story of the vanishing schoolmaster, Mr Scott, and the rumours that spread like wildfire one summer about his illicit affair with Agatha Jubber.

So begins Prudence's very first cold case . . .

Release date: February 15, 2024

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 380

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Too Many Cooks

Rosemary Shrager

The afternoon was growing old, but the journey from Prudence’s sleepy home village to the uttermost end of the earth (or ‘Cornwall’, as it was more commonly called) was a long one – and, owing to a three-hour traffic jam around Stonehenge, where at least the stranded drivers might gaze out upon the majesty of a few old stones, it had taken longer still. Now, with the light paling and the sun beginning its descent toward the sea, Prudence wondered if they were going to have to spend the night right here. It wasn’t that she hadn’t done her share of wild camping and foraging in her life – Prudence’s Meals for Nothing! had been a big hit in the latter stages of her career, and featured such startling recipes as ‘Nettle and Bilberry Tarte Tatin’ and ‘Rabbit and Seaweed Stew’ – but the scrubby roadside of Devil’s Corner did not immediately offer many opportunities to dig up delicacies from the natural world. There was, Prudence saw, a stand of fat hen – which did perfectly well in place of spinach – and she’d seen flowering yarrow in a hedgerow five hundred yards back. But, aside from this, there was just scrub grass and an occasional Coke can, no doubt thrown out of a passing car window. Hardly the basis of a feast, even for the most adept of cooks.

‘I’ve got a Twix, Grandma,’ said Suki, ferreting in her pocket. ‘And some gum.’

Prudence was on her hands and knees, contemplating how on earth you utilised a jack on a camper van. The thing seemed to be made for a Mini. She wondered why she’d bought it. ‘I’m quite good for gum, thank you, Suki,’ she said, cheerily. Suki, eighteen years old, was finally looking more like a professional kitchen assistant (her hair was still dyed black, but she had finally foregone the pale make-up which made her seem like a ghost) – but she was still alarmingly naive. ‘Gum won’t get us out of this, but good old elbow grease might.’

‘Gum might get us out of this, Grandma. There’s a TikTok here showing you how to patch a punctured tyre with Wrigley’s Extra. He’s doing it on a bike, but I imagine the principle’s the same.’

Prudence had stopped listening at the word ‘TikTok’, but when Suki repeated the advice, she just wryly shook her head and looked around. She could, at least, take in the beauty of their surroundings. This, she reasoned, was good for the soul – even if ferreting around in the dirt, with grease under your fingernails and blisters from using the wrench, wasn’t. It had been some decades since she last came along this road. Behind them, the fishing port of Penzance clung to the coastline – and, in front of her, only the pale blue of the summer sea. The cliffs here might have been perilous, but there was splendour in them as well. Beneath them stretched out all the manifold hidden beaches and coves of Cornwall. Only eight miles separated them from Land’s End, the furthest a soul could voyage in mainland Britain. For half a century she had carried this particular corner of the world in her soul. Breathing in the salt air was like breathing in a bit of her history. One day, when she finally settled down to write her memoirs (she had long ago decided to call it ‘The Pru Stew: Stories from My Life’), her years in this corner of the country would feature heavily, and showcase recipes like stargazy pie, hevva cake – and, of course, her own inimitable take on the traditional pasty.

‘Grandma, I think we—’

‘Yes, I know what I’m doing,’ said Prudence, whose cheer was finally giving way to exasperation. She had just smeared grease across her aquamarine glasses. They wouldn’t be so glitzy ever again.

‘No, Grandma, I think there’s . . .’

This time, Prudence looked up, meaning to tell Suki, in no uncertain terms, that she did not want any TikTok tips or advice from the nameless multitudes of Suki’s precious internet; what she wanted was for Suki to get down on her knees and engage with the problem in front of them. She was about to open her lips and say as much when she saw Suki pointing further along the coast road. Her eyes flashed in the same direction. Only partially obscured by the greasy smears on her glasses, Prudence finally saw what Suki had clocked some moments before: a second camper van was approaching along the coastal road. Dipping in and out of sight as it followed every bend, soon it was coming, in a cloud of dust, around the Devil’s Corner – where it promptly stopped, disgorging two girls of about Suki’s age, with Suki’s taste in dark clothing, dark make-up, and even darker expressions.

In a flash, Prudence was back on her feet, wringing her hands on one of the camper van’s dishcloths, then polishing her glasses on her sleeve. By the time a third girl, the driver, had stepped out of the new camper van, she considered herself at least reasonably presentable.

‘It’s you, isn’t it?’ the girl said, in a voice as shrill as one of Prudence’s old PR representatives every time she’d got Prudence the coveted slot on Saturday Kitchen. ‘I’d know that face anywhere!’

Prudence looked around. She suspected the reason the girls recognised her was more to do with the fact that her camper van, iconic in its vivid peach and cyan paints, bore the legend PRUDENCE BULSTRODE’S TRAVELLING KITCHEN in florid red letters. Even the numberplate, PRU BU 1, had a kind of fame of its own. Whatever the reason, Prudence was quite certain that girls of this generation had never watched any of her old television shows, nor browsed for her books in the libraries and bookshops where she still went to do readings and offer all manner of advice.

‘Girls, you catch us at a most unfortunate moment – but you might be our angels, come to earth. Now, do any of you know how to change a flat tyre?’

The faces of two of the girls flashed immediately to their own phones. A symphony of beeps and whirrs accompanied their frenzied attempts to find whatever instructional videos Suki had already unearthed.

It was the third girl, evidently the brains of the bunch, who shook her head wearily and declared, ‘I’ve got a better idea than that, Mrs Bulstrode. We’ll take you there ourselves.’

Prudence and Suki shared a look.

‘Well,’ the girl went on, ‘it’s only fair. You’ve come all this way to teach us cooking. We can hardly leave you standing on the side of the road like lemons, can we? Hop on up, Mrs Bulstrode. We can ask Ronnie Green, up at the school, to come back and change the tyre. Ronnie’s an absolute darl, he’s been handyman for twenty years. There isn’t a thing he doesn’t know about that school, or this coast. Well, what do you say?’ The girl grinned. ‘You’ll want to lock her up, Mrs Bulstrode.’ She looked up at the sky. ‘There’s a storm coming on. We’ll have to ask Ronnie to jump to it, or your camper’ll be blown clean over the cliff.’

The thought of this prompted Prudence to unload as many of her supplies as she could into the second camper van, which took some considerable time. By the time they hit the road again, sailing down the cliff road to the cove at the very bottom, darkness was curdling – but even this brought back memories for Prudence. In Prudence’s day, every journey along these old country roads had been undertaken by rickety old bus. The thought of girls as young as Suki owning cars, let alone camper vans, was quite unthinkable. But, as Suki insisted on telling her just about every other sentence, time kept on turning.

She was lost in thoughts like these when, all at once, they rounded the bend – and there, nestled in the cove beneath them, sat St Marianne’s School for Girls.

Prudence was not often given to waves of nostalgia, but one crashed over her now. From on high she could see the whole school: the west wing where the dormitories used to be, the hall and gymnasium, the outdoor blocks where girls did mathematics and science (as well as sewing and religion, quite often – when they had to make their own samplers – in the same lesson). There were the greenhouses, there the hockey pitch, there the kitchen garden and the very same building in which Prudence had taken her first ever domestic science lessons with dear old Mrs Jubber, and – for the first time – fallen in love with cookery.

‘Well, girls,’ she said, and tried to pretend that tears weren’t misting her eyes, ‘I have to say, I didn’t think I’d ever be back here. You won’t understand the gravity of this – not yet! – but it’s been nearly fifty whole years.’

‘Oh yes!’ the driver chirruped. She had introduced herself as Sophie, and had a double-barrelled surname with far too many syllables to safely pronounce. ‘We know all about it, Mrs Bulstrode. They’ve been talking about you coming ever since it was announced last Christmas. Your face has been in every newsletter. They’ve got a big picture of you up in the reception hall. A cardboard cut-out, no less – life-size! They’re very proud of you here, Mrs Bulstrode. And, well, when they invited sixth-formers to come back for a couple of weeks’ extra lessons over the summer break, a crash course from the world-famous television chef, well, we could hardly turn our noses up, could we? None of us can make more than a sandwich, Mrs Bulstrode – and Hetty here can’t even do that.’

One of the other girls, evidently named Hetty, looked up from her phone and shrugged. ‘I just don’t like bread,’ she remarked. ‘So I leave it out.’

Up ahead, the school was coming into clearer focus. Prudence could make out the groundskeeper’s little house, the little orchard where the girls used to pick apples and plums, the corner of the playground where she and her old friends used to gather and gossip.

Yes, she’d been quite unable to resist when the invitation landed. Two weeks, to run a crash course in cookery for girls from her alma mater, preparing them to go off into the world and fend for themselves. Now, that was the kind of commission Prudence’s retirement was made for.

‘Look, Suki,’ said Prudence, and took her grand-daughter’s hand, ‘it’s going to be a true trip down memory lane.’

Later, Prudence would look back and wonder at the simplicity of that statement.

Later, after the body had been found, she would wonder if all of her golden days here had been a lie.

But all of that was to come. For now, as they finally reached the boarding school and swung into the car park, Prudence was filled with all the wonderful feelings of a childhood revisited.

There was a little time yet, before murder reared its ugly head and changed everything.

Mrs Chastity Carruthers, forty-five years old (for the fourth time) and wearing the most garish of all the garish lipsticks found on the counter at Barker’s Department Store in Penzance, had been impatiently hopping about the school reception hall for some time when she saw the camper van approaching through the windows. At first, her heart sank – for this certainly wasn’t the camper van she’d seen in the glossy pages of Country Living, nor the article in Marks & Spencer magazine which had first prompted her to invite dear old Mrs Bulstrode back to the school – but then the doors opened up, and out stepped the very same lady whose cardboard cut-out was standing at her side, cardboard egg whisk in hand.

‘You look even better in the flesh, Mrs Bulstrode,’ she said to the cut-out. Then she rushed forward to open the school doors.

Mrs Carruthers, the doyenne – she preferred the word to ‘headmistress’, which made her seem so matronly – of St Marianne’s, had been rehearsing her welcome speech for some hours, slaving over it during a long, lonely night in the staffroom, but the moment she opened the doors, the rain started coursing down from the hills, robbing her of every breath. Consequently, it wasn’t until Prudence Bulstrode, her kitchen assistant, and three of the most disreputable girls attending the summer school had charged through the doors, that she found the wherewithal to speak. Even then, her carefully planned speech seemed to vanish.

‘Girls,’ she shrieked, ‘look at the state of you!’

She was referring to the copious amounts of black make-up, which were now cutting rivulets down the faces of her students, but suddenly she stopped, clapped a hand to her mouth, and started gabbling an apology to Prudence instead.

‘Oh, Mrs Bulstrode, please don’t think I meant you. You, Mrs Bulstrode, look just divine.’ She shot a look like daggers at the girls. ‘It’s this rain. It’s made a mess of everything, but we’ll have you dried out in a second. We can light the fire in the staffroom, should you wish – though we’ve radiators as well, of course, and have done for many long years! – and we’ll get you out of those dirty clothes and . . .’

Prudence had just about finished polishing her glasses again, when she felt Mrs Carruthers grappling with her arm. ‘I’m afraid we got caught on the headland. My camper van caught one of the potholes up there and burst its tyre, so we’re a little behind the times.’

‘Behind the times? No, Mrs Bulstrode, never! You mustn’t listen to what they say on these new-fangled cookery shows. You’re classical. You’re refined. You’re stately and traditional, and that’s precisely what these girls need.’

Prudence saw the look she was giving the students again – she’d been on the receiving end of one or two looks like those back in her own schooldays – and decided to throw the girls one of her own looks: this one filled with commiseration and understanding.

‘I’ll have Ronnie get your camper van back to base, Mrs Bulstrode. We simply must have the Pru-mobile here for when classes begin. There’s a local photographer very keen to document the whole thing – for posterity’s sake, you understand – and she’ll be more keen than ever to have that camper in shot. Just think of the headlines: “Local Wonder Returns to the Stage”. We’re proud as punch to have you, Mrs Bulstrode. Proud as punch.’

Prudence had three times tried to get a word in, but Mrs Carruthers evidently had no intent on letting her. Suddenly, she was barking orders at the girls – ‘Find Ronnie Green, and find him this instant!’ – and steering Prudence along the hallway. Prudence, who was rather used to excitable PR assistants whisking her along – but was yet to meet a headmistress quite as excitable – threw the girls another consolatory look as she departed. Suki, beached somewhere between them, seemed to think momentarily about following the girls, then trotted after her grandmother instead.

‘Of course, Ronnie’s got an awful lot on this summer,’ Mrs Carruthers was saying as they ventured from the reception hall, deeper into the school’s achingly familiar warren of corridors. As they went, the rush of old feelings was almost overpowering to Prudence. It wasn’t that the school hadn’t changed since her day – modernisation was the name of the game for schools as suddenly moneyed as this. Rather, it was that the feel of the place had somehow been retained. The footsteps echoed in the very same way. Somehow, the smell of beeswax and vinegar polish rolling out of the performance hall was the same, redolent of those heady summers in the 1970s when Pru and her friends had staged shows here. The way the light fell into the corridor outside the school office sparkled just as it had in 1974. The noise of the rain drumming on the plate glass windows . . .

‘Oh yes, lots,’ Mrs Carruthers went on, quite oblivious to the way Prudence was daydreaming. ‘I’m afraid it’s fallen to dear Ronnie to organise the contractors. You’ll soon see, Mrs Bulstrode, that time marches on here at St Marianne’s. Thanks to a very generous local investment, we’ve raised the funds to erect a state-of-the-art gymnastics facility – so I’m afraid it’s goodbye to the hockey pitches, and hello to the St Marianne’s Olympic Arena!’

Prudence wasn’t quite sure why St Marianne’s girls needed a state-of-the-art gymnastics facility at all – what gymnast needed more than a few bars and a pommel horse? – but she wasn’t sad to hear that the hockey pitch was to be no more. She’d been three times passed over as hockey captain in her time here, and (yes, she knew it was pathetic) it had rankled ever since.

At once, Mrs Carruthers stopped dead and turned on her heel. Prudence, whose daydreaming stopped just as suddenly, realised they were standing outside the site of the school staffroom. Several times, she’d been compelled to stand here, awaiting the emergence of whichever teacher was about to admonish her and her friends for some minor infraction. She glanced sideways at Suki. Yes, she thought, it was better not to share memories like this with Suki; Prudence’s grand-daughter had only just found the road marked ‘straight and narrow’ herself.

‘I completely forgot to tell you. You and I, Mrs Bulstrode, have a very special connection.’

‘Oh yes?’ asked Prudence, whose fans often said something along a similar line.

‘Indeed we do. Mrs Bulstrode, I’m proud to announce that I was born on the very same day you were awarded this . . .’

And Mrs Carruthers stepped aside, to reveal a single certificate – now browned around the edges, yellowed with age – mounted behind the Perspex glass of a wallhanging display.

Prudence had to creep a little closer to see exactly what it said.

PRUDENCE BULSTRODEForm 13aHAS BEEN AWARDED THEST MARIANNE’S PRIZE FOR HOME ECONOMICS12 June 1976

Presented by:MISS AGATHA JUBBERDomestic Sciences

‘Oh,’ said Prudence, and felt another rush of fond memories. ‘But . . . but this hasn’t been up on the wall all these years, surely?’

‘Oh no, Mrs Bulstrode, it’s been in the school archive – looked after by our erstwhile librarian. I chanced across it some time ago, and I’ve been hoarding it ever since. You see, Mrs Bulstrode, I rather feel as if we both began in the very same moment. Our stories are as one. Here you were, trotting up to stage to meet this Miss . . .’ Mrs Carruthers had to squint at the certificate to make sure she had the name right, ‘ . . . Jubber, taking what I like to think is your very first step towards being the nation’s sweetheart, the shining light of the cookery world. And there was I, my head just crowning, my little face appearing between my mother’s—’

‘I see,’ said Prudence, tactfully, before Mrs Carruthers was able to continue that particular description. ‘Well, I have to say, it is rather remarkable.’ What was truly remarkable was that Suki was not already corpsing with laughter. ‘And I remember that day very well. Miss Jubber – well, that really is where it started for me. I have Miss Jubber, and this school, to thank for all of it. Without Miss Jubber, I don’t think I’d have fallen in love with food at all. Somehow, she just made it so alive. When we were in that classroom . . .’ It was hard to put it into words, that magical feeling of finding your vocation, of falling headlong into it and realising, suddenly, that your entire life was being mapped out. ‘I shall enjoy cooking in the domestic science block again.’

‘It isn’t quite like you used to know it,’ said Mrs Carruthers, wagging her finger. ‘We’re a little more state of the art than we were. All the ovens are voice activated now, of course. And the smart fridges can tell you exactly when your eggs are on the turn.’

Prudence thought: So could I, by simply dropping them in a bowl of cool water. But she managed not to breathe a word.

‘Well, shall we get going then?’ Prudence ventured. ‘Dinner with the staff tonight, isn’t it? I made sure we transferred as many of our packs from my camper van as we could. We didn’t quite gather everything up, but there’s more than enough to get started.’ By instinct, Prudence rolled her sleeves up and wrung her hands together, as if in keen anticipation. ‘Any requests, Mrs Carruthers? I’m quite able to make a menu up on the spot. In fact, I rather think of it as my party piece. And I was thinking . . . Well, the school kitchens here used to serve the most dreadful beef and dumplings. For dessert: treacle sponge. I had it in mind, Mrs Carruthers, that I might jazz up the old menu. Show you all what beef and dumplings can really be like . . .’

Mrs Carruthers’ face had suddenly contorted. ‘Oh, but Mrs Bulstrode, don’t you think of it! You cook for us? Well, I should be delighted, of course, to have any meal cooked by a lady of your pedigree – but you’re our star, you’re our guest of honour, you’ve come back to this school to give back to our students what we once gave to you. There’ll be plenty of cookery going on this week, but tonight you’re to be cooked for.’

Prudence screwed up her eyes. ‘Mrs Carruthers, I wasn’t aware that you wanted to rustle something up – but really, it’s no problem to me if . . .’

‘Me?’ Mrs Carruthers squawked, then threw her head back in such laughter that Mrs Finch, Prudence’s old drama teacher, would have summarily ejected her from the classroom for overacting. ‘Mrs Bulstrode, unless you want jammy toast, I shan’t be cooking for you tonight. No, we have something much better in store. We’re to take you out on the town. We have a wonderful evening planned to welcome you back – a trip to the most hip, happening place from here to Tintagel Castle.’ She inclined her head, as if to share in some confidence. ‘The Bluff, Mrs Bulstrode. It’s the pride of Penzance. Two Michelin stars, and just waiting on a third. You must have heard of it? The chef there, didn’t you do a show with him once?’

Prudence didn’t have to dredge her memory banks particularly deeply to summon up this oddity. The Bluff had sat on a lonely corner of coastland west of Penzance for half a generation, but only recently had it achieved the stardom over which Mrs Carruthers was salivating. That was down to the efforts of a young chef named Benji (though Prudence was quite certain his mother hadn’t christened him with that particular spelling) Huntington-Lagan, one of the rising stars who’d got his start in cookery by posting endless videos of himself online, videos in which he sought to tutor others in skills he’d scarcely seemed to master himself. He and Prudence had been partnered together for a celebrity challenge one year, in honour of the BBC’s Comic Relief charity appeal. It was the kind of thing Prudence’s old agent used to sign her up for without hesitation – because, of course, it was ‘just puuuurrrrrr-fect for the public prrrrr-ofile, darling’ – and that was how Prudence Bulstrode had ended up as one of the eight competitors in Chefs Go Ape, tasked with cooking a three-course dinner for a troop of mountain gorillas in the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in deepest, darkest Uganda.

Through gritted teeth, and with a perfectly painted on smile, Prudence said, ‘It sounds fantastic. I can’t wait to see how Benji’s getting on. He’s certainly . . . grown his brand,’ that terrible saying he used to parrot every other sentence, ‘since we worked together.’

‘Yes, and let’s hope he isn’t serving us up grubs fit for a gorilla,’ grinned Mrs Carruthers. Then, her face suddenly darkening, she turned to Suki and said, ‘You can sort out Mrs Bulstrode’s supplies while we’re gone, dear. Make sure everything’s ship-shape for her return.’

Suki had her face buried in her iPhone, no doubt looking up the indignity that was Chefs Go Ape, so there was a second’s silence before she looked up, bemused. By then, Prudence had already weighed in: ‘Suki’s very much a part of the team, Mrs Carruthers. Where I go, Suki goes. This girl’s learning so fast that, someday soon, she won’t need me at all . . .’

‘But still learning,’ said Mrs Carruthers, her heels clicking as she marched on. ‘Mrs Bulstrode, this is a night for the adults. Some adult companionship and conversation. And . . . well, our table’s already booked.’

‘It’s all right, Grandma,’ said Suki, quietly. ‘I’m not sure I’m in the mood for . . .’ And she squinted at the menu on her phone as if trying to decipher hieroglyphics. ‘Deconstructed Cornish Lobster Wellington, Sequestered in a Saffron and Parmesan Velouté. Or . . .’ This next was even more difficult to get her mouth around. ‘Peruvian Ceviche Amidst Clusters of Sea-kale and Salsify Gel.’ Suki looked up, puzzled. ‘Grandma, why does it say “Aggravated Shrimp”?’

Prudence lowered her voice. ‘Because chefs like Benji can’t just serve scampi and chips, my dear.’

‘I don’t mind giving this one a miss, Grandma. I can take the packs up to our rooms, and I did promise I’d call Mum when we got here.’

Prudence nodded. Of course, what Suki didn’t know was that Prudence had observed her messaging a boy named ‘Doogie’ (what was wrong with the good old names? Where were the Matthews and Thomases any more?) every time they stopped on the long road west. No doubt, what Suki actually intended to do was dash off a quick text to her mother, then spend the rest of the evening sending little hearts and pictures back and forth with this boy she’d met. Well, you were only young once – a fact that Prudence was being starkly reminded of, now that she walked through her old school halls – and perhaps the evening would flash by more swiftly if she didn’t have to keep an eye on her grand-daughter as well.

Then, tomorrow morning, they could get on with the proper business for which they’d been hired: Prudence Bulstrode, passing on all the knowledge she’d acquired in a long, storied career to the next generation of young cooks.

There was almost something poetic about it.

‘Save me some tea and toast, Suki,’ Prudence whispered as she and Mrs Carruthers hurried away. ‘I have a feeling I’ll need something to settle my stomach after our visit to the Bluff . . .’

Coastal rain is the most dramatic kind of rain. It churns up the ocean, merges sea and sky, turns the world to a shifting, rippling curtain of grey.

So it was as Mrs Carruthers’s private driver chauffeured both the headmistress and Prudence along the winding, clifftop road – until, some distance further west, they reached the little fishing port of Castallack Cove.

The village itself had grown since Prudence used to come this way: she and the girls from St Marianne’s, out on their bicycles on a lazy Sunday afternoon – off, perhaps, to meet one of the boys from St Cuthbert’s on the other side of the cove. Prudence herself hadn’t had much time for those boys (well, not many of them), but among her friends there had been girls with an insatiable appetite – not necessarily for the boys, but certainly for the thrill that came with breaking a sacred school rule. A few more houses had been built, and the village post office had been joined by a little café and delicatessen – but, compared to the sprawl of London, progress here was practically mute.

That was why the Bluff, sitting on the headland above the town, up a long, sweeping track with only the restaurant as its destination, stood out so starkly.

It had been a local watering hole in Prudence’s day. A pub that served perfect pasties and fish and chips – and, on a Sunday, whole roast pollock and plaice. Back then, the Bluff had taken a ‘progressive’ view with underage drinkers, and Prudence was quite sure she’d had her first illicit tipple up here, a cider lemonade which would have made her feel quite giddy if it hadn’t been for the crispy whitebait at the bar.

Now, however, everything had changed. As the car reached the top of the headland, Prudence saw that only the shell of the old Bluff remained. Instead of the old fisherman’s retreat, there now stood a gleaming palace of white stone and plate glass. Pale mauve light spilled out of the front windows, with a constellation of miniature stars gleaming around the welcoming door. Taken in its craggy, windswept surroundings – and especially with the rain still lancing down – it looked to Prudence like the bastard offspring of a novel by Daphne du Maur. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...