Prologue

There are the facts, and then there is the truth.

These are the facts.

It is the summer solstice, June 1991.

You’re only nine years old. You’re short for your age. The school nurse has recommended that you lose weight. You struggle to make friends and often feel lonely. You have been bullied. Teachers and your parents frequently encourage you to participate more in group activities, but you prefer the company of your imaginary friend.

We know you spend time that night in Stoke Woods because when you get home, leaves and pine needles are found on your clothing and in your hair, there is dirt beneath your fingernails, and you reek of bonfire smoke.

Home is number 7 Charlotte Close, a modest house identical to all the others on a short cul-de-sac built in the 1960s on a strip of land sold for development by a dairy farmer. It is situated adjacent to Stoke Woods, a couple of miles from the famous Suspension Bridge that links this semirural area directly to the city of Bristol.

We know you arrive home at 1:37 A.M., three hours and six minutes before dawn.

As for the rest of what happened, you describe it many times in the days that follow, and you paint, of course, an exceptionally vivid picture, because even at that age you have a facility with words.

You tell it this way:

The stitch in your side feels like a blade, but you daren’t stop or slow as you race through the woods toward home. Trees are gathered as far as you can see with the still menace of a waiting army. Moonlight winks through the canopy and its milky fragments dot and daub the understory. The shifting light shrinks shadows, then elongates them. Perspective tilts.

You drive forward into thicker undergrowth where normally you tread carefully but not tonight. Nettles rake your shins and heaps of leaf mold feel as treacherous as quicksand when your shoes sink beneath their crisped surface. The depths below are damp and grabby.

It’s a little easier when you reach the path, though its surface is uneven and small pebbles scatter beneath your soles. Your nostrils still prickle from the smell of the bonfire.

It’s easy to unlatch the gate to the woods’ car park, as you’ve done it many times before, and from there it’s only a short distance to home.

Each step you take slaps down hard on the pavement and by the time you reach Charlotte Close, everything hurts. Your chest is heaving. You’re gasping for breath. You stop dead at the end of your driveway. All the lights are on in your house.

They’re up.

Your parents are usually neat in silhouette. They are tidy, modest folk.

A bonus fact: including you and your little brother, the four of you represent, on paper, the component parts of a very ordinary family.

But when the front door opens, your mother explodes through it, and the light from the hall renders her nightgown translucent so you have the mortifying impression that it’s her naked body you’re watching barrel up the path toward you, and there’s nothing normal about that. There’s nothing normal about anything on this night.

Your mum envelops you in her arms. It feels as if she’s squeezing the last of your breath from you. Into the tangled mess of your hair she says, “Thank God,” and you let yourself sink into her. It feels like falling.

Limp in her tight embrace, you think, please can this moment last forever, can time stop, but of course it can’t, in fact the moment lasts barely a second or two, because as any good mother would, yours raises her head and looks over your shoulder, down the path behind you, into the darkness, where the street lighting is inadequate, where the moonlight has disappeared behind a torn scrap of cloud, where the only other light is rimming the edges of the garage door of number 4, and every other home is dark, and she says the words you’ve been dreading.

“But where’s Teddy?”

You can’t tell them about your den.

You just can’t.

Eliza would be furious.

Your mum is clutching you by your upper arms so tightly it hurts. You have the feeling she might shake you. It takes every last ounce of your energy to meet her gaze, to widen your eyes, empty them somehow of anything bad she might read in them, and say, “Isn’t he here?”

1.

I typed “The End,” clicked the save button, and clicked it again just to make sure. I felt huge relief that I’d finished my novel, and on top of that a heady mixture of elation and exhaustion. But there were also terrible nerves, much worse than usual, because typing those words meant the consequences of a secret decision that I’d made months ago would have to be faced now.

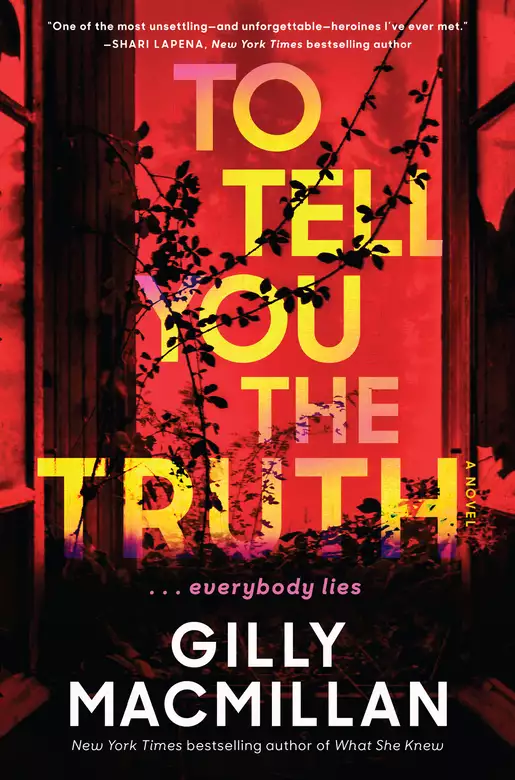

Every year I write a new book, and the draft I’d just finished was my fifth novel, a valuable property, hotly anticipated in publishing houses in London, New York, and other cities around the world. “Valuable property” were my literary agent’s words, not mine, but he wasn’t wrong. Every day as I wrote, I imagined the staccato tapping of feet beneath desks as publishers awaited the book’s delivery, and this time I felt extra nervous because I knew I was going to send them something they weren’t expecting.

“Brave,” Eliza had said once she’d figured out what I’d done.

“I’m sorry,” I told her, and I meant it. Her voice had a new and nasty rasp to it, but everything has its price. Under different circumstances, Eliza would be the first to point that out, because my girl is pragmatic.

I knew what I had to do next, but it was scary. I had a routine for summoning courage, because it was always hard to find, frequently lost in the scatter and doubt of writing a novel.

Counting to thirty took longer than it should have because I decelerated—I am a master of avoidance—but when I got to zero, I focused like a sniper taking aim. One tap of the finger and the novel was gone, out there, 330 pages on their way to my agent, via email, and it was too late to change anything now.

I waited as long as a minute before refreshing my inbox to see if he had acknowledged receipt. He hadn’t. I deleted emails from clothing retailers offering me new seasonal discounts because I thought they were traitorous messages, reminding me of my internet shopping habit at a moment when something more significant was happening, though I did glimpse a jumpsuit that I thought I might revisit later. It was a buttery color, “hot this spring” apparently and “easy to accessorize.” Tempting and definitely worth another look, but not now.

I drummed my fingers on my desk. Refreshed again. Nothing. I clicked the back button and checked if they had the jumpsuit in my size. They did. No low-stock warning, either. Nice. I added one to my shopping cart anyway. Just in case. Went back to email. Refreshed again. Still nothing. Checked my spam folder. Nothing there from Max, but good to see that hot women were available for sex in my city tonight. I deleted all spam, re-refreshed my inbox once more. No change.

I picked up the phone and called. He answered immediately. He has a lovely voice.

“Lucy! Just a second,” he said, “I’m on the other line. Let me get rid of somebody,” and he put me on hold. He sounded excited and it made me feel a little fluttery. Not because I’m attracted to him, please don’t get the wrong idea, but because he’s the person I plot and plan my career with, the gatekeeper to my publishers, negotiator-in-chief of book deals, firefighter-in-chief when things go pear-shaped, and recipient of a percentage of my earnings in return.

Max and I need each other; I’m his most successful client by far, so it was no surprise that he’d been trying to contain his impatience as my deadline for submitting the first draft of this book had approached, delivering pep talks and confidence boosts via phone and email. Whenever I met him, I noticed his nails were bitten to the quick.

He came back on the line after just a moment. “I’m all yours.”

“It’s done.”

“You. Bloody. Miracle.” I heard his keyboard clatter as he checked his email. “Got it,” he said. There was a double-click as he opened the document. I imagined his eyes on the first page. Seconds passed. They felt like millennia.

“Max?”

Was he reading it? Was he gripped by the first few lines of my story, or had he scanned a few pages ahead and already felt the cold wrap of horror, the clutch of disappointment? My nerves were shredded enough that I could catastrophize a three-second pause.

“I’ll read it immediately,” he said. “Right away. You must put down the phone and go directly to celebrate. Do not pass go. Treat yourself. Have a bath, open a bottle of something delectable, tell that husband of yours to spoil you. I’ll call you as soon as I’ve finished it.”

At the very start of my career, before I had visited Max’s office, I used to try to imagine what it was like. I thought he was the type to have a leather chair well-stuffed enough to cradle his buttocks in comfort and a big desk, its surface large and polished so that it reflected light from the window it faced, which was probably ornate, containing leaded glass perhaps, or framed with elaborate stonework. That’s the sort of person Max seemed to me to be, in spite of his bitten nails: a puppet master. Only a puppet master would have a desk like that. I shared that thought with him once—we must have sunk a few cocktails, or I wouldn’t have been brave enough to say it out loud—and he half smiled, the expression aligning his asymmetric features.

“But you’re the one who has the power of life and death,” he replied. “Fictionally speaking,” he added after a beat.

True.

Beyond the chair, the desk, and the architectural features, I also imagined that Max’s office would be messy. Beautiful bones framing disorder was how I saw it and it was a very attractive image, to me.

I could find beauty in surprising things. You have to when violence reverberates through your work. I imagine every thriller writer will have their own way of handling this.

And, by the way, when I finally got to visit Max’s office in person, I found it to be nothing at all like what I had expected.

2.

After Max, Daniel, my husband, was always the second person to know when a book was finished, but I wanted a few moments to myself before I told him, moments when I didn’t feel watched, because I felt like people watched me all the time.

My first novel had been published four years ago and exploded onto the crime fiction scene (my publisher’s words, not mine) and high onto the bestseller list, where it stayed for months. And I was introduced to the concept of a book a year—something Max and my editors insisted on as being of paramount importance. Since then people had taken extreme notice of me. They watched what I was writing next and learned to deduce how quickly I was writing it. They watched me at events. Online. They watched like hawks. They bombarded me with messages on social media. I even had one fan, so far unidentified, who had located the house in which Dan and I rented our flat—a modest building in a graffiti- and coffee-shop-speckled neighborhood of Bristol—and left gifts on the doorstep.

The presents weren’t really for me, though. The heroine of my novels was Detective Sergeant Eliza Grey. She was based on my childhood imaginary friend. (Write what you know, they say, and I did.) People were mad for Eliza and those gifts were for her. They included her favorite condiment (cloudberry jam—discovered when she was working on a case in Oslo in book two) and her favorite beverage (a caffeinated energy drink). They made me uneasy, I won’t lie, however well-intentioned they were. I asked Dan to get rid of them. They felt like an intrusion into my private life.

It had profoundly shocked me, how suddenly and completely I had become public property after the publication of my first Eliza book. I hadn’t anticipated it, and had I known it would happen, I might never have sent my novel out to literary agents in the first place. The minute I’d signed over the rights to that book, nobody cared that my natural inclination was to curl around my privacy as tightly as a pill bug.

My moment of aloneness in the office was disappointing. Instead of basking in a sense of peaceful privacy (as opposed to the fraught loneliness that usually characterized my writing days), I could only see the mess.

I’d shut myself in that room for weeks to get the book finished, working on a crazy schedule of late nights and dawn starts, sometimes a frenzy of typing in the early hours, interspersed with snatches of fractured sleep. My circadian rhythm had been more tarantella than waltz and it showed. Even my printer looked tired, its trays askew, fallen paper on the floor beneath it: A courtesan whose client has just left. She dreams of marrying him. (But I mustn’t personify my printer. What will you think of me?) The floor and coffee table were hardly visible beneath a townscape created from piles of printed drafts and research materials.

“Should you really dump your stuff on an authentic Persian rug?” Dan had asked from the doorway a few weeks ago, when the surfaces could no longer contain all the clutter and it had begun to creep over the floor. I hadn’t thought of it that way. I was more used to soft furnishings from IKEA, we both were, it’s all we had ever known, but we were at a point where Dan was getting accustomed to the finer things in life and growing into the new wealth my books had brought us more quickly than I was. He had the time to luxuriate in it and to figure out how to spend it; I didn’t. My writing schedule saw to that. I couldn’t afford to look up from my work and enjoy the change in our lives. I was barely aware it was happening.

It wasn’t just the fancy rug that took some getting used to. The cottage we were renting was also a reflection of what we found ourselves newly able to afford. The weekly rate had seemed eye-watering to me when Dan first proposed the idea, an insult to my natural inclination to be economical and unflashy, but Dan had insisted that we needed to be here.

“You can’t do the final push on this book in the flat,” he’d said with an irritating air of authority, honed for years on the subjects of writing and the creative process, but recently applied more frequently to our domestic life. “It’s too claustrophobic. We’ll be on top of each other.”

He was right, and I knew it, but I loved writing in our cozy one-bed flat with its views of the little row of shops opposite, and the smells from the bakery wafting across the street every morning. And I felt superstitious. I’d written all my books so far in that flat. What if a change of routine affected my writing? What if it signaled that I had gotten above myself? Everyone knows that tall poppies are the first to be decapitated.

But even as those anxieties raised a swarm of butterflies in my stomach, I knew I had to take Dan’s wishes carefully into consideration because he worked full-time for me now, and it made the issue of who had the power in our household a delicate one. I tried to think of how to frame my objections to renting the cottage in a way that wouldn’t upset him, but I got tongue-tied. Words flow for me when I’m writing, but they can stick in my throat like a hairball when I have to speak up for myself.

Dan softened his tone to deliver the winning line: “We can easily afford it, I’ve looked at the numbers, and imagine being in the countryside . . . by the ocean, too. It’ll be so good for us.”

I was susceptible to emotional blackmail, and to the potential for romance. Writing is a lonely job, as I’ve said. I also had to trust him on the money, because he managed my finances for me. Trying to grapple with taxes and columns of numbers plunged me into panic.

I agreed to rent the place and watched him click “Book Now,” but as he did, I had the strange feeling that life had somehow just shifted a little bit beyond my control.

There’s something else I should mention, in the spirit of full disclosure.

On paper, ours was a nice, mutually beneficial, privileged arrangement where I would write a thriller each year and continue to rake in the money, and Dan would provide all the support I needed, but there was a large and rather revolting fly stuck in the ointment, its legs twitching occasionally.

The fly was this: Being my assistant wasn’t the life Dan had dreamed of. He’d wanted to be a bestselling author, too.

I.

On the night Teddy disappears, you wait until midnight before trying to leave the house. You’re eager to get going because dawn will break in just a few hours and it’s only until then that the spirits will be out, moving among real people, making mischief, playing tricks.

You know what happens on the summer solstice because you researched it in the library. You are a very able nine-year-old. “Exceptionally bright,” your teacher wrote in your report. “Reading and writing to a level well beyond her age.”

Your bedroom door creaks and the noise cuts right through you. You count to ten and nothing happens, so you think you’re safe, and you step out onto the landing, but Teddy’s door opens when you’re right outside it.

“What are you doing?” he says.

You shush him, hustle him into his bedroom, helping him back into bed, nestling his blankie by his head the way he likes it.

“Go back to sleep,” you whisper. You stroke his hair. He puts his thumb into his mouth and sucks. His eyelids droop. You force yourself to stay there until you’re sure he’s gone back to sleep.

You’ve just crept over to his bedroom door when he says, “Lucy, I want you.”

Your fingers clench. You very badly want to go out into the woods. You’ve been planning this for weeks. You turn around. He looks sweet, lying there.

“Do you think you can be really quiet?” you say.

“Teddy can be quiet.” He refers to himself in the third person more often than not. Later, someone will say it’s as if he always knew he wouldn’t be with us for long.

“Don’t take him with you,” Eliza says in your head. Your imaginary friend always has an opinion.

“He’ll cry if I don’t,” you reply silently, “and wake up Mum and Dad.”

“Then you can’t go.”

That’s not an option you want to consider. You hold out your hand and Teddy’s eyes brighten.

“Do you want to come on an adventure?” you ask him.

3.

Sitting in my office alone, I didn’t just feel disappointed, I also felt guilty, because the end of a book was happy news and Dan deserved to share it right away. My schedule was punishing for both of us, and he needed these moments of celebration just as much as I did.

I levered myself up from my seat, left my lair with a sense of traversing a portal, and found him in the kitchen, stirring a casserole. I watched him for a moment before he sensed me. He seemed preoccupied by something, the wooden spoon doing little more than troubling the surface of the food.

“Hi,” I said from the doorway. He turned and half smiled, evidently trying to assess my state of mind, his first instinct at this stage of a book to be wary of me. Here I was, his very own Gollum whose precious obsession was a novel. Had she finished? Finally? Or had her glazed and bloodshot stare been fixed on a blinking cursor at the top of a blank page, while at the far end of her optic nerve, her mind shredded itself with doubt?

I saw those questions in his eyes and had the stupid idea that it might be fun to break the tension by conveying that I had good news to share by doing a little victory dance. I tapped one fist on top of the other, twice, then swapped over. Got my hips swaying. Kept it jaunty. It took a lot of concentration in the exhausted state I was in, and I might have been frowning, but I wanted to try it because it was the sort of thing that he and I used to do all the time, a frivolous language we shared with one another that made us giggle.

But Dan’s eyes widened. It was as if he didn’t know how to speak frivolous anymore—or didn’t want to. I stopped, awash with self-consciousness. He flipped the dishcloth he was holding over his shoulder and cleared his throat. “How’s it going?” he asked. He was wearing a novelty apron I’d bought him, with the slogan “I can cook as good as I look.”

He did look good, sleek and composed, buffed and polished. The Dan I’d met seven years ago, that shabby, pudgy guy running on creative passion and budget groceries, had been transformed by the injection of money. He wasn’t just taking care of his appearance but had worked on improving himself in other ways, too. He knew about wine now. He’d invested in a fancy car. He’d even encouraged me to get a stylist, but I hadn’t had the time to do that, or to keep up with him in other ways. The only efforts I’d made to improve were my occasional splashy online clothing purchases, and even then, I was never quite sure whether I’d bought the right thing.

I also wasn’t exactly certain when Dan’s pattern of transformation had begun. While I wrote my second book? The third? After that big royalty check? The book-a-year schedule meant that time was sometimes confusing to me, its linearity a deck of cards that could be reshuffled. Creating fiction left no mental space for orderly recollections of reality. I thought of my memories as tall grasses that could be blown this way or that.

“Your memories were like that before you started writing,” Eliza muttered. I couldn’t deny it. Eliza and I were always honest with one another.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved