“Iknow what you’re going to say when I tell you that I am two hundred and forty-six years old. You’ll roll your eyes, smirk, perhaps, probably with your arms folded at your chest, and think to yourself ‘the old boy’s cheese has slid quite a distance from his cracker.’

“Well, then the joke’s on you, as I haven’t kept my cheese or cracker in the same place for a long, long while. I am Vestus Addison Schmoyer, and I’m as old as independence. I slid from my mother’s womb just days before the great document was signed, while the streets of Philadelphia were glut with the joyous cavorting, wrapped in a drapery of rapturous song, the ushering in of a broad-shouldered new period of living.

While the newly dressed nation was unfurling fresh, wet wings, I was suckling a scabrous teat in the dank hold of a marooned fishing boat, stranded on the mucky shore of the septic Delaware river. My mother spent my first moments swatting away rats that were just as famished as her mewling son. As I fed, she wept and watched the fat, furred creatures devour the cord and afterbirth she’d kicked to the side after cutting me free of fleshy shackle with a rusted sliver of tin. The squeals of the rats and I were an indecipherable chorus that lulled my sweet mother to permanent sleep. Her blood pooled beneath us like a warm slippery quilt. Red as life, it was. The rats went to work on the poor woman and left me to sleep in her lap.

It was there I would be found by a young fisherman, Barton Gand, the following morning, when he would notice a stream of bloated rats leaving the vessel in a pulsating line. Would note the faint flicker of candlelight through the broken boards of the hull. Would lift me from the gory crib of my mother and carry me out into the bleary eyed world. I suppose I ought to hate him for that...”

“I wasn’t aware that one day, the vermin and I would be kin. Siblings in tenacity and resilience. A coal black vein threading us together and to the moon as though we were the tail of a terrific midnight kite.”

The old man stopped speaking, and with a slightly shaking finger, wiped the dollop of spittle from the corner of his mouth. He smiled and nodded his head quickly, a mimicry of a bow.

“Man, oh man, Ken, I get chills every time you do that. I mean, I know you wrote it and all, but so long ago and you just recite it as though it’s fact. Like you’re remembering your kid’s high school graduation or your wedding day or something.”

The old man winced a little at those comparisons, but the young nurse fellow was smiling so big, his hairy cheeks could barely cage it and he did not notice. Tierny looked over at the boy, who was also smiling but slightly shaking his head in either embarrassment or indifference. He’d heard this before, several times.

The old man smiled, then finished drinking from his cup. He sat it on the table beside the worn copy of Midnight Rictus, the only book that had ever brought Ken Allenwood acclaim and a somewhat steady income. The only one still mentioned on lists and horror fanzine write ups, mostly due to the wretched film version that came about decades earlier. Ken was not bitter though; the checks had cleared and had paid for the necessary things. He had written the novel, and he had the story in him, as much as his spine and heart. Whatever the movie studio people did or didn’t do with it, mattered nil. He picked up the book and looked at the cover with fondness. The black matte painted night sky was broken only by the hint of a smile made up of many small points.

“I signed it for you, I even used the fountain pen that I wrote the original longhand draft with all those years ago.”

With a trembling hand, he held it out to the nurse who took it gingerly.

“Well, Tierny, let me tell you where I learned to read publicly. I learned from one of the very best back when I was first coughing words onto the page. His name was Robert Denial, and because the world is an unjust place, a cruel place, he never seemed to claw his way to the ranks of the biggies. His fans are ferocious in their loyalty though. Every single book he eked into the world is gold. Look him up next time you’re at the library. Ol’ Bob was a gentle man, a smile that could cover any wound or occasion. The warmest, he was. To watch him do a reading was like watching a one man play by a consummate actor. He stalked the room, no regard for size, and looked every person in the eye, then personally took them by the hand, and led them into his territory. He almost never read from a book or page, choosing to memorize the material and deliver it as though mining from memory. I’ve watched him reduce them to tears or provoke riotous laughter; he held them all right in the palm of his fucking hand, I tell you. An absolute master, he was. A beautiful soul.”

“Is he still writing?” The question came from Tierny.

“Sadly, no. He left us many years ago. His demons got the reins, I fear. Left him along the soul road, chewed up by the world and spat out as gristle. That’s what it does, you know. Eats and swallows and regurgitates...over and over, forever. Fucking tragedy.”

At the second use of the explicit curse, the boy chuckled low, nearly under his breath, and turned the page of his monster magazine. He looked up and the old man gave him a wink. Elijah nodded even though his mind was beginning to wander, as it usually did. Tierny was still smiling at both the man and the boy, but his mouth was not matched by his eyes. They held a slight sadness. Tierny knew that this was just a longer pocket of clarity in a sea of befuddlement and confusion that would grow deeper and choppier over the coming months. He’d watched it devour many and would see it masticate many more. He held the book close to his chest, thought of the old man carefully exacting his signature on the first page for him. He would hold it as treasure for the rest of his days, and though something sharp jabbed his heart, he kept the smile on for both of them.

Ken was having a good day today.

A clear day. An On point day. Now, at least. The rest of the day seemed up in the air.

When Elijah had come over earlier, just before lunch but after his mother had left for her shift at the factory, Ken was sitting in the recreation room. It was really just a big room with three couches, a chair, a TV on the wall, and plenty of space for wheelchair parking, and for walkers poised at the ready.

Ken was in the large recliner closest to the wall, his head tipped back with his eyes mostly closed. Elijah had watched him sleep for long minutes, watched his eyes roll beneath the thin lids. He slowly and calmly rested a hand on the old man’s forearm and gently squeezed.

“Mr. Ken?” He whispered.

Ken’s eyes popped open in surprise, but he didn’t jump or cry out. He looked at the boy for a few seconds, the lack of knowledge as to who he was, glaringly apparent. His brow furrowed in dark confusion, but then, the wrinkles there began to smooth out and a warm recognition blossomed in his expression. His thin lips rose in a smile and his bony hand found the boy’s, still on his arm. Ken’s skin was so thin and cool, Elijah thought, as he rubbed his thumb over the old man’s. It was a comforting gesture; his mother had done it when he was a little boy, scared by something and unable to sleep. He figured this whole dementia thing must be terrifying for Ken, so he did what he could.

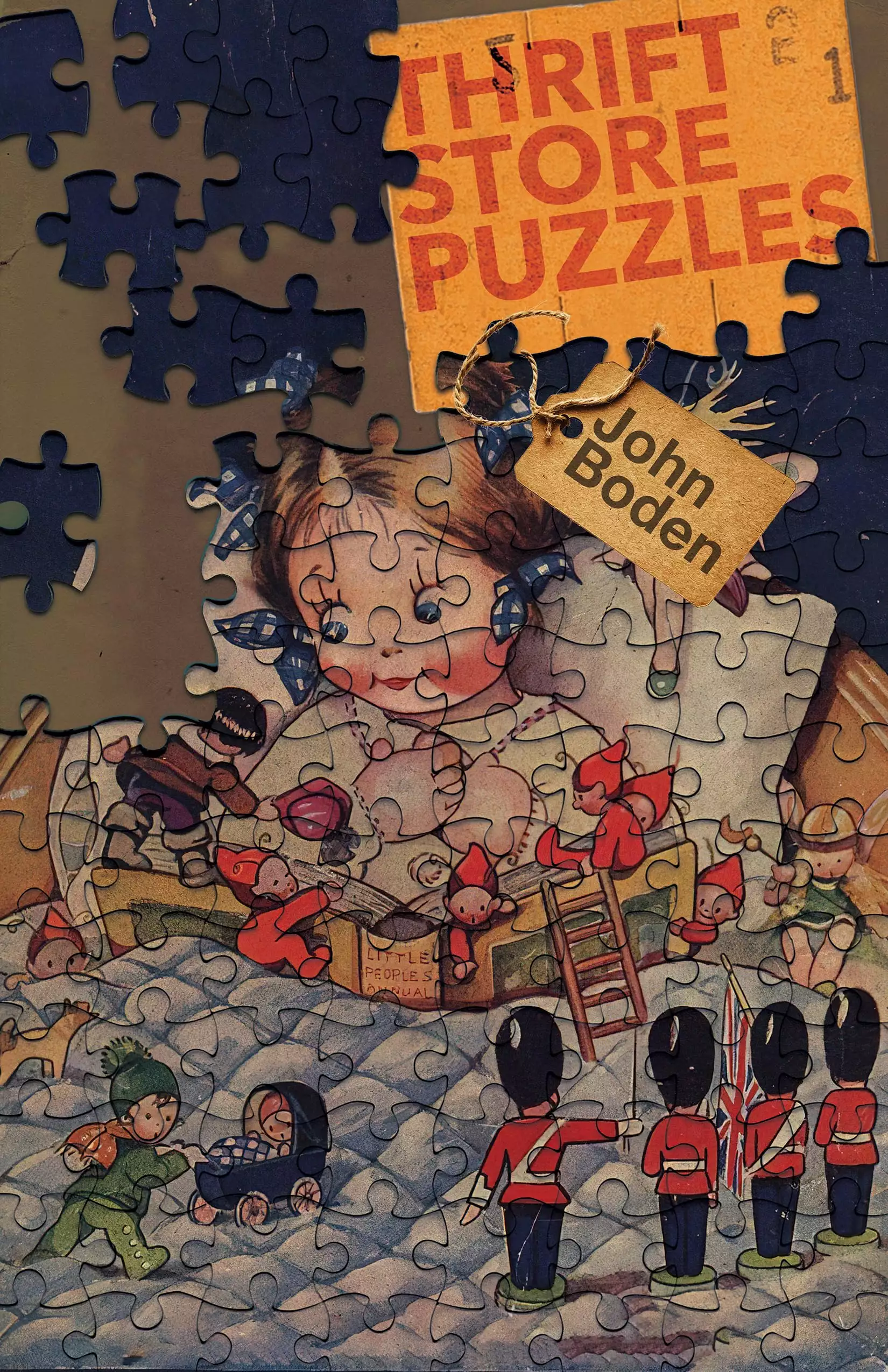

“It means his brain is slowing and breaking down, kiddo. It means a lot more than that and a lot more details than I can even go into but the gum of it is that. Old Ken is losing things. Little things now and then but, eventually, all of it. He won’t recall anyone or much of anything. It’s like a puzzle from the thrift store, there are pieces missing and no matter how much time and attention you give it, it will never be complete.”

Tierny had told Elijah that weeks earlier. He had just crossed the street from his house and was making his way to the facility’s side entrance when he heard Tierny whistle. The bearded man had been out under the willow tree sneaking a smoke. He said he had to tell him something because he knew he liked to visit Ken and listen to his stories and keep the man company. He had leaned over to look the boy in the eye, a courtesy most adults never bothered to extend, and laid it on him.

Elijah wasn’t a little kid. He was thirteen and four months. He was not as tall as his peers, but he knew that would change one day. His mother had promised him, and that woman never told a lie. He knew what was tragic when he heard it. He knew sadness well, and when he felt tears broadcasting the news about his elderly friend, he felt no shame in them.

Tierny went on to explain, in his matter-of-fact way, that what this all meant was that eventually Ken would not remember Elijah. He wouldn’t be able to place his face or Tierny’s or Nurse Paula’s or anyone else’s who saw him every day. He’d forget his own face and history. A glimpse in the mirror would be a window to a grizzled stranger. His beloved stories would become pages torn from a bizarre book,

written in a foreign language. He would just fade, one memory or function at a time, until he was gone. Essentially disappeared.

“He’ll disappear.” Tierny had said, as he sucked the cigarette between his fingers down to the end. He bared his teeth like some woodland beast, smoke leaking from between them. His eyes were wet with tired tears. Elijah felt his throat fill with something thick.

His eyes promised more of their own salt water. He nodded and slipped inside, leaving Tierny in his cove of whispering shade to feed his lungs their shadows.

“Oh hello, boy.” The old man spoke, his usually clear and commanding voice fragile in that moment with phlegm and age.

“And I beg you, plead even...drop the Mister jazz.” They both chuckled then. ...