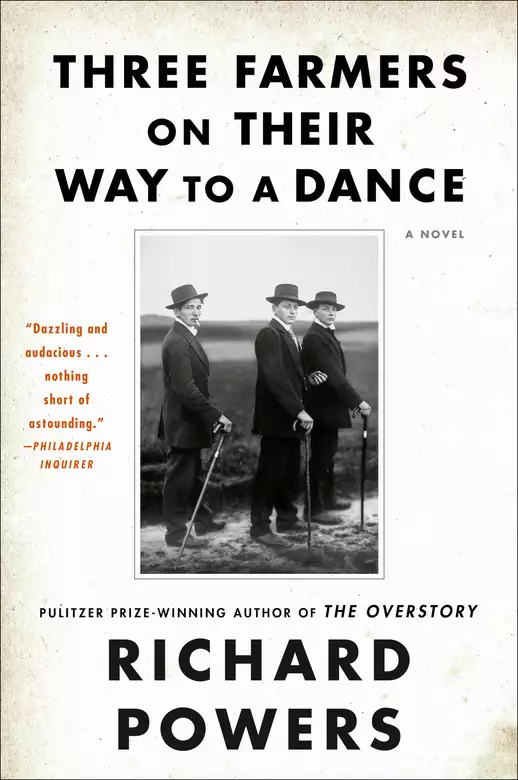

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In the spring of 1914, renowned photographer August Sander took a photograph of three young men on their way to a country dance. This haunting image, capturing the last moments of

innocence on the brink of World War I, provides the central focus of Powers’s brilliant and compelling novel. As the fate of the three farmers is chronicled, two contemporary stories unfold. The young

narrator becomes obsessed with the photo, while Peter Mays, a computer writer in Boston, discovers he has a personal link with it.

The three stories connect in a surprising way and provide the reader with a mystery that spans a century of brutality and progress.

Release date: June 22, 2021

Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance

Richard Powers

Chapter OneI Outfit Myself for a Trip to Saint Ives

Cats, kits, sacks, wives: how many were going to St. Ives?

For a third of a century, I got by nicely without Detroit. First off, I don’t do well in cars and have never owned one. The smell of anything faintly resembling car seats gives me motion sickness. That alone had always ranked Motor City a solid third from bottom of American Cities I’d Like to See. I always rely on scenery to deaden the inconvenience of travel, and “Detroit scenery” seemed as self-contradictory as “movie actress,” “benign cancer,” “gentlemen of the press,” or “American Diplomacy.” For my entire conscious life I’d successfully ignored the city. But one day two years ago, Detroit ambushed me before I could get out of its way.

The Early Riser out of Chicago dropped me off alongside Grand Trunk Station, a magnificent building baptized in marble but now lying buried in plywood. I lugged my bag-and-a-half into the terminal, a public semidarkness stinking of urine and history. Subpoenaed relatives met their arriving parties under the glow of a loudspeaker that issued familiar, reassuring tunes.

One hundred years ago, the Grand Trunk must have quickened pulses. Pillars of American Municipal balanced a fifty-foot vault on elaborate Corinthian capitals: America copying England copying France copying Rome copying the Greeks. A copper dome with ceramic floral trim bore the obligatory inscriptions from Cicero and Bill Taft. Now the station’s opulence left it a mausoleum, empty except for the Early Riser executives who threaded the rotunda in single file.

I fell automatically into line, sensing the station’s lavout. The soaring ceiling seemed out of proportion to the size of the hall. When my eyes adjusted to Detroit’s industrial-grade light, I received a shock, the same shock

industrial-grade light, I received a shock, the same shock I had felt as a child when, at a public swimming pool, I saw an old vet unstrap and remove his leg before taking a dip. The antique terminal had been similarly amputated: the corridor I walked down was not the station’s length but only its width. The Grand Trunk had been sent packing: plywood sheets boarded off palatial wings and multiple gates, leaving only this reduced chicken run between a lone arrival platform and the main exit.

Transferring trains in Detroit was the cheapest if not the most expedient way of getting from Chicago to Boston. Drastically cut fares promoted a new route, the Technoliner, for the first month of its run. The line subsequently folded, the technolinees long ago forsaking Detroit for Houston and northern California, and even longer ago forsaking trains for planes. Another case of our railway being behind schedule. Nevertheless, I sank as low as Toledo to take advantage of the reduced fare.

When I’m in money, I can leave half-eaten meals in restaurants along with the best. I’ve worked hard at overcoming a natural stinginess. But when I’m out of money—a cyclical occurrence paralleling America’s boom/bust economy of the last century—I easily fall back on old habits. This trip found me once again short, having just spent a year in the Illinois backwoods on a small business project that did not pan out. “Pan out” comes, I assume, from the prospectors’ days. Flash in the pan. I spent my early thirties in isolation, chasing flashes in the pan.

With my technical background, I knew that I could find work in Boston providing I could put down a security deposit on an efficiency and still have enough cash left over to dry-clean my interview suit. My money margin, marginalia in this case, did not worry me so much as the immediate problem of how to spend the six hours between the Early Riser and the Technoliner in a city I had, until then, celebrated by avoiding. It was me against motion sickness in the city autos built.

But as sometimes happens when killing time, I would come across something in my brief Detroit layover that would kill not just six hours but the next year and more before I came to terms with it. Sifting the downtown for novelties that might deaden ten minutes, I did not imagine that the next ten months would find me obsessed with

I had felt as a child when, at a public swimming pool, I saw an old vet unstrap and remove his leg before taking a dip. The antique terminal had been similarly amputated: the corridor I walked down was not the station’s length but only its width. The Grand Trunk had been sent packing: plywood sheets boarded off palatial wings and multiple gates, leaving only this reduced chicken run between a lone arrival platform and the main exit.

Transferring trains in Detroit was the cheapest if not the most expedient way of getting from Chicago to Boston. Drastically cut fares promoted a new route, the Technoliner, for the first month of its run. The line subsequently folded, the technolinees long ago forsaking Detroit for Houston and northern California, and even longer ago forsaking trains for planes. Another case of our railway being behind schedule. Nevertheless, I sank as low as Toledo to take advantage of the reduced fare.

When I’m in money, I can leave half-eaten meals in restaurants along with the best. I’ve worked hard at overcoming a natural stinginess. But when I’m out of money—a cyclical occurrence paralleling America’s boom/bust economy of the last century—I easily fall back on old habits. This trip found me once again short, having just spent a year in the Illinois backwoods on a small business project that did not pan out. “Pan out” comes, I assume, from the prospectors’ days. Flash in the pan. I spent my early thirties in isolation, chasing flashes in the pan.

With my technical background, I knew that I could find work in Boston providing I could put down a security deposit on an efficiency and still have enough cash left over to dry-clean my interview suit. My money margin, marginalia in this case, did not worry me so much as the immediate problem of how to spend the six hours between the Early Riser and the Technoliner in a city I had, until then, celebrated by avoiding. It was me against motion sickness in the city autos built.

But as sometimes happens when killing time, I would come across something in my brief Detroit layover that would kill not just six hours but the next year and more before I came to terms with it. Sifting the downtown for novelties that might deaden ten minutes, I did not imagine that the next ten months would find me obsessed with everything I could learn about Motor City and the fifth-grade farmer who put it on the map.

When I made my stopover, Detroit had already been undergoing a manufactured and heavily publicized rebirth for some time. The emblem of this new era, the Renaissance Center, may be the single most ambitious building project of recent times. Its five black towers outscale the rest of the city the way Chartres Cathedral dwarfs its surrounding town. Four cylinders flank a central, massive pillar, each hanging black glass over girders in disguised International Style.

But if the city were not already dead, would it need a rebirth? The name “Renaissance Center” resembles an ad campaign declaring Sudso “All the cleaner you’ll ever need,” or a restaurant assuring, “What we serve is really a meal.” And just as when telling an old widower that he looks well we mean he ought not to push his luck, the leading citizens of Detroit, in naming the Renaissance Center, implied that they would be pleased if the city could, at this point, break even.

The size and opulence of the center meant to attract tourists and conventioneers into double-A, self-contained luxury. The palace executed its purpose too well. It drew people (read money) up and away from the surrounding businesses, and because the towers were so self-sufficient a village, the people never came back out. The area surrounding the Renaissance Center showed the signs of a hasty evacuation and rout. Gravitating toward the towers, I passed row on row of brick, triple-decked residences standing vacant, their windows and doors broken open to reveal nothing inside.

I figured that the Renaissance Center (dubbed the Ren Cen by those who make a living truncating all words into monosyllables) would be good for a half hour. The inside was a contemporary version of the Grand Trunk—the multileveled, involuted architecture that had delighted me as a boy of six, when I still believed in Tom Swift and urban renewal. I ordered a meal, reading the menu right to left, in a disk-shaped restaurant floating on a moat in the central tower, spinning, gradually but perceptibly, driven no doubt by a thousand minimum wage-slaves chained to a mill-track on a hidden lower level.

My training in physics made the huge spinning plate seem an unintentional homage to the last, great empirical

experiment of the nineteenth century. In 1887, the physicists Michelson and Morley set out to measure the absolute velocity of the earth through the ether field. The two scientists floated a gigantic slab on a sea of mercury, on the same scale and setup as the slab I now rode. They shone a beam of light through a prism in the center and back to mirrors on the perimeter, reasoning that light flowing in the direction of the ether stream would travel faster than light flowing upriver. But Michelson and Morley found no difference in light speeds, regardless of orientation. An international calamity followed in 1905, when Einstein, a Bern patent clerk with no reputation to lose, suggested preserving the velocity of light at the expense of the concept of absolute measure. The century was off to a quick jump out of the gate.

I came across an account of this experiment again much later, after pursuing the Henry Ford hoax through the infant century. But at the time, I drew the comparison casually. I waited until the disk completed one full rotation before disembarking. Since I don’t smoke or drink and swear unconvincingly, symmetry is my only vice. Escaping from the Ren Cen, I walked counterclockwise for a few blocks to reverse my dizziness. I sat down on the nearest set of steps. A bum approached from across the piazza and requested a quarter for some suntan oil. I explained that I needed it to dry-clean my interview suit and he left me in peace.

Nearby, a vintage ’50s statue depicted a green, cupreous titan hefting a petite, state-of-the-art, Waspish couple in one hand and either a globe or an automobile—I can’t remember which—in the other: Spirit of Detroit. Two lawyers fist-fought over a parking space. A woman sold clods of earth out of a shoe box. A man with a ventriloquist’s dummy explained to an indifferent crowd that the present secretary of state was the Antichrist. A prominent clock harped on the fact that I was doing a rotten job marking time. If I was going to make it to the Technoliner intact, I’d need better diversion.

I bused to the Detroit Institute of Arts. Now the finest of this century’s paintings will never make up for our concurrent botch of everything else. Art can only hope to be an anaesthetic, a placebo. The best artists know that patients always fake their symptoms and must be tricked into diagnosis before treatment can take place. The last

I had felt as a child when, at a public swimming pool, I saw an old vet unstrap and remove his leg before taking a dip. The antique terminal had been similarly amputated: the corridor I walked down was not the station’s length but only its width. The Grand Trunk had been sent packing: plywood sheets boarded off palatial wings and multiple gates, leaving only this reduced chicken run between a lone arrival platform and the main exit.

Transferring trains in Detroit was the cheapest if not the most expedient way of getting from Chicago to Boston. Drastically cut fares promoted a new route, the Technoliner, for the first month of its run. The line subsequently folded, the technolinees long ago forsaking Detroit for Houston and northern California, and even longer ago forsaking trains for planes. Another case of our railway being behind schedule. Nevertheless, I sank as low as Toledo to take advantage of the reduced fare.

When I’m in money, I can leave half-eaten meals in restaurants along with the best. I’ve worked hard at overcoming a natural stinginess. But when I’m out of money—a cyclical occurrence paralleling America’s boom/bust economy of the last century—I easily fall back on old habits. This trip found me once again short, having just spent a year in the Illinois backwoods on a small business project that did not pan out. “Pan out” comes, I assume, from the prospectors’ days. Flash in the pan. I spent my early thirties in isolation, chasing flashes in the pan.

With my technical background, I knew that I could find work in Boston providing I could put down a security deposit on an efficiency and still have enough cash left over to dry-clean my interview suit. My money margin, marginalia in this case, did not worry me so much as the immediate problem of how to spend the six hours between the Early Riser and the Technoliner in a city I had, until then, celebrated by avoiding. It was me against motion sickness in the city autos built.

But as sometimes happens when killing time, I would come across something in my brief Detroit layover that would kill not just six hours but the next year and more before I came to terms with it. Sifting the downtown for novelties that might deaden ten minutes, I did not imagine that the next ten months would find me obsessed with everything I could learn about Motor City and the fifth-grade farmer who put it on the map.

When I made my stopover, Detroit had already been undergoing a manufactured and heavily publicized rebirth for some time. The emblem of this new era, the Renaissance Center, may be the single most ambitious building project of recent times. Its five black towers outscale the rest of the city the way Chartres Cathedral dwarfs its surrounding town. Four cylinders flank a central, massive pillar, each hanging black glass over girders in disguised International Style.

But if the city were not already dead, would it need a rebirth? The name “Renaissance Center” resembles an ad campaign declaring Sudso “All the cleaner you’ll ever need,” or a restaurant assuring, “What we serve is really a meal.” And just as when telling an old widower that he looks well we mean he ought not to push his luck, the leading citizens of Detroit, in naming the Renaissance Center, implied that they would be pleased if the city could, at this point, break even.

The size and opulence of the center meant to attract tourists and conventioneers into double-A, self-contained luxury. The palace executed its purpose too well. It drew people (read money) up and away from the surrounding businesses, and because the towers were so self-sufficient a village, the people never came back out. The area surrounding the Renaissance Center showed the signs of a hasty evacuation and rout. Gravitating toward the towers, I passed row on row of brick, triple-decked residences standing vacant, their windows and doors broken open to reveal nothing inside.

I figured that the Renaissance Center (dubbed the Ren Cen by those who make a living truncating all words into monosyllables) would be good for a half hour. The inside was a contemporary version of the Grand Trunk—the multileveled, involuted architecture that had delighted me as a boy of six, when I still believed in Tom Swift and urban renewal. I ordered a meal, reading the menu right to left, in a disk-shaped restaurant floating on a moat in the central tower, spinning, gradually but perceptibly, driven no doubt by a thousand minimum wage-slaves chained to a mill-track on a hidden lower level.

My training in physics made the huge spinning plate seem an unintentional homage to the last, great empirical experiment of the nineteenth century. In 1887, the physicists Michelson and Morley set out to measure the absolute velocity of the earth through the ether field. The two scientists floated a gigantic slab on a sea of mercury, on the same scale and setup as the slab I now rode. They shone a beam of light through a prism in the center and back to mirrors on the perimeter, reasoning that light flowing in the direction of the ether stream would travel faster than light flowing upriver. But Michelson and Morley found no difference in light speeds, regardless of orientation. An international calamity followed in 1905, when Einstein, a Bern patent clerk with no reputation to lose, suggested preserving the velocity of light at the expense of the concept of absolute measure. The century was off to a quick jump out of the gate.

I came across an account of this experiment again much later, after pursuing the Henry Ford hoax through the infant century. But at the time, I drew the comparison casually. I waited until the disk completed one full rotation before disembarking. Since I don’t smoke or drink and swear unconvincingly, symmetry is my only vice. Escaping from the Ren Cen, I walked counterclockwise for a few blocks to reverse my dizziness. I sat down on the nearest set of steps. A bum approached from across the piazza and requested a quarter for some suntan oil. I explained that I needed it to dry-clean my interview suit and he left me in peace.

Nearby, a vintage ’50s statue depicted a green, cupreous titan hefting a petite, state-of-the-art, Waspish couple in one hand and either a globe or an automobile—I can’t remember which—in the other: Spirit of Detroit. Two lawyers fist-fought over a parking space. A woman sold clods of earth out of a shoe box. A man with a ventriloquist’s dummy explained to an indifferent crowd that the present secretary of state was the Antichrist. A prominent clock harped on the fact that I was doing a rotten job marking time. If I was going to make it to the Technoliner intact, I’d need better diversion.

I bused to the Detroit Institute of Arts. Now the finest of this century’s paintings will never make up for our concurrent botch of everything else. Art can only hope to be an anaesthetic, a placebo. The best artists know that patients always fake their symptoms and must be tricked into diagnosis before treatment can take place. The last thing I expected to find at the Institute was a mystery, a work of art demanding to be tracked down, a trail unfolding indefinitely, approximately, the way memory tries “recoil,” or “recommend,” or “record,” coming as close as “recoup,” but never alighting on its real object, “recover.”

The foyer of the Detroit museum opens onto yet another Grand Hall, a high-vaulted, Euro-sick, stone rectangle entirely unfit for displaying works of art. Rococo satyrs and curlicues alternate with heat-duct grills in a confused architectural legacy. In 1931, in the depths of the Depression, the Institute’s Arts Commission, backed by Edsel Ford, asked the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera to use the room for a fresco commemorating the greatness of Detroit.

It was an odd marriage: Edsel Ford, whose father was the first among capitalists, in cahoots with Rivera, the notorious revolutionary who secured Trotsky’s political asylum in Mexico. Rivera, the Third World champion, praising the city whose chief icon is an enormous electric sign tallying new autos as they come off the assembly ramp. Diego, who once incorporated a wall fuse box into a mural, working in a room the gaudy copy of Bourbon splendor. But Detroit and Diego shared something critical: both were in love with machines.

The Institute put up ten thousand dollars of Edsel’s cash, embarrassed to offer “the only man now living who adequately represents the world we live in—wars, tumult, struggling peoples” such a meager sum. They suggested he limit his work to fifty square yards on each of the two larger walls, one hundred dollars per square yard, by some esoteric formula, considered fair for a man of Diego’s stature. Thus the Fords, standing in for Michelangelo’s papal patrons, might have suggested the fellow not do the whole ceiling, but just a little bit above the altar. Rivera grew increasingly ambitious in guilty compensation for the gringos’ liberality. Edsel, finding out that Diego meant to cover all four walls, upped the ante to twenty-five thousand.

The Institute told Diego that they “would be pleased if [he] could possibly find something out of the history of Detroit, or some motive suggesting the development of industry in this town.” They did not suspect that the huge man would cart his bulk through all the factories of

Detroit, holing up for over three months at Ford’s, Chrysler’s, and Edison’s plants, sketching thousands of preliminaries. Rather than appease the room’s rococo anachronisms, he blitzed them with a vision swept up off the factory floor. And in the final work, the curlicues and satyrs go unnoticed, lost in Diego’s mechanical vision.

Rivera worked behind a screen for two years, an hourly laborer painting sometimes sixteen hours a day, in a room whose glass roof created greenhouse temperatures of over 100 degrees. Journalists, glimpsing the work in progress, declared that the murals, far from praising the city, would “knock Detroit’s head off.” The unveiling provided plenty for all those who secretly love a thunderstorm. The crowd stood baffled by the revealed work, seeing no historical allusions or civic allegories, no lineup of leading Detroit power brokers. The public flocked all the way out to the museum to see what they were forced to see every other day of the week: ordinary, characterless people chained to endless, sensual machines.

Diego had committed the principal subversive act: he painted the spirit of Detroit in all its unretouched particulars. Strings of interchangeable human forms stroked the assembly line—a sinuous, almost functional machine—stamping, welding, and finally producing the finished product—an auto engine. Men in asbestos suits and goggled gas masks metamorphosed into green insects. Languorous allegorical nudes mimicked the conveyor. The frescoed room showed the spirit of Detroit from a much closer distance than the comfortable, corporate copper titan I had passed on the street outside. Viewers at the unveiling found themselves inside Detroit, just as the mural-men crawled in, around, and over their creation, striking a mutually parasitic relationship with metal. Diego had painted a chapel to the ultimate social accomplishment, the assembly line, a self-reproducing work of art, precise, brilliant, and hard as steel.

Bishops and businessmen instantly mobilized to destroy the frescoes. It is not hard to read subversion and heresy into the average work of a person’s hands. The task becomes easier when the work is ambitious, joyful, and revolutionary. Rivera’s was a duck shoot. Even those who had not yet visited the museum found a garden variety of blasphemies in the work. People saw a

I had felt as a child when, at a public swimming pool, I saw an old vet unstrap and remove his leg before taking a dip. The antique terminal had been similarly amputated: the corridor I walked down was not the station’s length but only its width. The Grand Trunk had been sent packing: plywood sheets boarded off palatial wings and multiple gates, leaving only this reduced chicken run between a lone arrival platform and the main exit.

Transferring trains in Detroit was the cheapest if not the most expedient way of getting from Chicago to Boston. Drastically cut fares promoted a new route, the Technoliner, for the first month of its run. The line subsequently folded, the technolinees long ago forsaking Detroit for Houston and northern California, and even longer ago forsaking trains for planes. Another case of our railway being behind schedule. Nevertheless, I sank as low as Toledo to take advantage of the reduced fare.

When I’m in money, I can leave half-eaten meals in restaurants along with the best. I’ve worked hard at overcoming a natural stinginess. But when I’m out of money—a cyclical occurrence paralleling America’s boom/bust economy of the last century—I easily fall back on old habits. This trip found me once again short, having just spent a year in the Illinois backwoods on a small business project that did not pan out. “Pan out” comes, I assume, from the prospectors’ days. Flash in the pan. I spent my early thirties in isolation, chasing flashes in the pan.

With my technical background, I knew that I could find work in Boston providing I could put down a security deposit on an efficiency and still have enough cash left over to dry-clean my interview suit. My money margin, marginalia in this case, did not worry me so much as the immediate problem of how to spend the six hours between the Early Riser and the Technoliner in a city I had, until then, celebrated by avoiding. It was me against motion sickness in the city autos built.

But as sometimes happens when killing time, I would come across something in my brief Detroit layover that would kill not just six hours but the next year and more before I came to terms with it. Sifting the downtown for novelties that might deaden ten minutes, I did not imagine that the next ten months would find me obsessed with everything I could learn about Motor City and the fifth-grade farmer who put it on the map.

When I made my stopover, Detroit had already been undergoing a manufactured and heavily publicized rebirth for some time. The emblem of this new era, the Renaissance Center, may be the single most ambitious building project of recent times. Its five black towers outscale the rest of the city the way Chartres Cathedral dwarfs its surrounding town. Four cylinders flank a central, massive pillar, each hanging black glass over girders in disguised International Style.

But if the city were not already dead, would it need a rebirth? The name “Renaissance Center” resembles an ad campaign declaring Sudso “All the cleaner you’ll ever need,” or a restaurant assuring, “What we serve is really a meal.” And just as when telling an old widower that he looks well we mean he ought not to push his luck, the leading citizens of Detroit, in naming the Renaissance Center, implied that they would be pleased if the city could, at this point, break even.

The size and opulence of the center meant to attract tourists and conventioneers into double-A, self-contained luxury. The palace executed its purpose too well. It drew people (read money) up and away from the surrounding businesses, and because the towers were so self-sufficient a village, the people never came back out. The area surrounding the Renaissance Center showed the signs of a hasty evacuation and rout. Gravitating toward the towers, I passed row on row of brick, triple-decked residences standing vacant, their windows and doors broken open to reveal nothing inside.

I figured that the Renaissance Center (dubbed the Ren Cen by those who make a living truncating all words into monosyllables) would be good for a half hour. The inside was a contemporary version of the Grand Trunk—the multileveled, involuted architecture that had delighted me as a boy of six, when I still believed in Tom Swift and urban renewal. I ordered a meal, reading the menu right to left, in a disk-shaped restaurant floating on a moat in the central tower, spinning, gradually but perceptibly, driven no doubt by a thousand minimum wage-slaves chained to a mill-track on a hidden lower level.

My training in physics made the huge spinning plate seem an unintentional homage to the last, great empirical experiment of the nineteenth century. In 1887, the physicists Michelson and Morley set out to measure the absolute velocity of the earth through the ether field. The two scientists floated a gigantic slab on a sea of mercury, on the same scale and setup as the slab I now rode. They shone a beam of light through a prism in the center and back to mirrors on the perimeter, reasoning that light flowing in the direction of the ether stream would travel faster than light flowing upriver. But Michelson and Morley found no difference in light speeds, regardless of orientation. An international calamity followed in 1905, when Einstein, a Bern patent clerk with no reputation to lose, suggested preserving the velocity of light at the expense of the concept of absolute measure. The century was off to a quick jump out of the gate.

I came across an account of this experiment again much later, after pursuing the Henry Ford hoax through the infant century. But at the time, I drew the comparison casually. I waited until the disk completed one full rotation before disembarking. Since I don’t smoke or drink and swear unconvincingly, symmetry is my only vice. Escaping from the Ren Cen, I walked counterclockwise for a few blocks to reverse my dizziness. I sat down on the nearest set of steps. A bum approached from across the piazza and requested a quarter for some suntan oil. I explained that I needed it to dry-clean my interview suit and he left me in peace.

Nearby, a vintage ’50s statue depicted a green, cupreous titan hefting a petite, state-of-the-art, Waspish couple in one hand and either a globe or an automobile—I can’t remember which—in the other: Spirit of Detroit. Two lawyers fist-fought over a parking space. A woman sold clods of earth out of a shoe box. A man with a ventriloquist’s dummy explained to an indifferent crowd that the present secretary of state was the Antichrist. A prominent clock harped on the fact that I was doing a rotten job marking time. If I was going to make it to the Technoliner intact, I’d need better diversion.

I bused to the Detroit Institute of Arts. Now the finest of this century’s paintings will never make up for our concurrent botch of everything else. Art can only hope to be an anaesthetic, a placebo. The best artists know that patients always fake their symptoms and must be tricked into diagnosis before treatment can take place. The last thing I expected to find at the Institute was a mystery, a work of art demanding to be tracked down, a trail unfolding indefinitely, approximately, the way memory tries “recoil,” or “recommend,” or “record,” coming as close as “recoup,” but never alighting on its real object, “recover.”

The foyer of the Detroit museum opens onto yet another Grand Hall, a high-vaulted, Euro-sick, stone rectangle entirely unfit for displaying works of art. Rococo satyrs and curlicues alternate with heat-duct grills in a confused architectural legacy. In 1931, in the depths of the Depression, the Institute’s Arts Commission, backed by Edsel Ford, asked the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera to use the room for a fresco commemorating the greatness of Detroit.

It was an odd marriage: Edsel Ford, whose father was the first among capitalists, in cahoots with Rivera, the notorious revolutionary who secured Trotsky’s political asylum in Mexico. Rivera, the Third World champion, praising the city whose chief icon is an enormous electric sign tallying new autos as they come off the assembly ramp. Diego, who once incorporated a wall fuse box into a mural, working in a room the gaudy copy of Bourbon splendor. But Detroit and Diego shared something critical: both were in love with machines.

The Institute put up ten thousand dollars of Edsel’s cash, embarrassed to offer “the only man now living who adequately represents the world we live in—wars, tumult, struggling peoples” such a meager sum. They suggested he limit his work to fifty square yards on each of the two larger walls, one hundred dollars per square yard, by some esoteric formula, considered fair for a man of Diego’s stature. Thus the Fords, standing in for Michelangelo’s papal patrons, might have suggested the fellow not do the whole ceiling, but just a little bit above the altar. Rivera grew increasingly ambitious in guilty compensation for the gringos’ liberality. Edsel, finding out that Diego meant to cover all four walls, upped the ante to twenty-five thousand.

The Institute told Diego that they “would be pleased if [he] could possibly find something out of the history of Detroit, or some motive suggesting the development of industry in this town.” They did not suspect that the huge man would cart his bulk through all the factories of Detroit, holing up for over three months at Ford’s, Chrysler’s, and Edison’s plants, sketching thousands of preliminaries. Rather than appease the room’s rococo anachronisms, he blitzed them with a vision swept up off the factory floor. And in the final work, the curlicues and satyrs go unnoticed, lost in Diego’s mechanical vision.

Rivera worked behind a screen for two years, an hourly laborer painting sometimes sixteen hours a day, in a room whose glass roof created greenhouse temperatures of over 100 degrees. Journalists, glimpsing the work in progress, declared that the murals, far from praising the city, would “knock Detroit’s head off.” The unveiling provided plenty for all those who secretly love a thunderstorm. The crowd stood baffled by the revealed work, seeing no historical allusions or civic allegories, no lineup of leading Detroit power brokers. The public flocked all the way out to the museum to see what they were forced to see every other day of the week: ordinary, characterless people chained to endless, sensual machines.

Diego had committed the principal subversive act: he painted the spirit of Detroit in all its unretouched particulars. Strings of interchangeable human forms stroked the assembly line—a sinuous, almost functional machine—stamping, welding, and finally producing the finished product—an auto engine. Men in asbestos suits and goggled gas masks metamorphosed into green insects. Languorous allegorical nudes mimicked the conveyor. The frescoed room showed the spirit of Detroit from a much closer distance than the comfortable, corporate copper titan I had passed on the street outside. Viewers at the unveiling found themselves inside Detroit, just as the mural-men crawled in, around, and over their creation, striking a mutually parasitic relationship with metal. Diego had painted a chapel to the ultimate social accomplishment, the assembly line, a self-reproducing work of art, precise, brilliant, and hard as steel.

Bishops and businessmen instantly mobilized to destroy the frescoes. It is not hard to read subversion and heresy into the average work of a person’s hands. The task becomes easier when the work is ambitious, joyful, and revolutionary. Rivera’s was a duck shoot. Even those who had not yet visited the museum found a garden variety of blasphemies in the work. People saw a ridiculous Saint Anthony tempted away from his foreman’s plans by an allegory nude’s legs. Depression-sensitive capitalists saw in the figures communist-inspired proto-humans. A panel showing the inoculation of a child burlesqued the Nativity.

Diego’s compliment—that Detroit reveled in the vitality of the machine age—became, in the mouths of its interpreters, an insult. Edsel, the people declared, had been taken in by a piece of dangerously populist propaganda. An organized outcry of radio broadcasts and written petitions culminated in the Detroit News saying that “the best thing to do would be to whitewash the entire work completely.”

The work stood. Those cooler minds in the opposition knew that whitewashing turns an ambiguous work decidedly subversive, whereas a busy and ambitious mural was its own death kiss. Left alone, it would date itself more and more each year, playing to an increasingly disinterested house until one day, with the roots of civilization still intact, it would pass a magic milestone and become that perfectly harmless, even socializing item, the historical artifact.

I knew nothing of all this as I stood in the mural room between trains, nor did I suspect that I would be caught up in finding out. Viewed from inside the factory, the self-reproducing machine demanded allegiance or resentment, but denied the possibility of indifference. Technology could feed dreams of progress or kill dreams of nostalgia. The old debate came alive in Rivera’s work with a new strangeness. The machine was our child, defective, but with remarkable survival value. Rivera had painted the baptismal portrait of a mutant offspring, demanding love, resentment, pity, even hope, but refusing to be disowned.

With new eyes, I noticed a minor panel on one of the small walls, off to the side of the conveyor murals. In front of a sculpted dynamo more erotically contoured than any nude, a white-haired man sat at a monolithic desk, face pinched into an amalgam of benevolence and greed—Ford or Edison or De Forest or any of a dozen crabbed industrialists and innovators.

In this face, the face of our times, lay all the evidence I would need to break the hoax, to crack the mystery. Had I recognized the composite face for what it was, I might have saved a year spent tracking down the other leads:

Detroit, Rivera, Ford, the auto, mechanical reproduction, portraiture, ether, relativity. When we don’t know what we are after, we risk passing it over in the dark. The Chinese played with fireworks for hundreds of years without inventing the gun. Edison thought his moving pictures were just toys. The physician who first set out to discover appropriate anaesthetic dosages discovered, instead, addiction. And I, thinking the clues to my discomfort lay elsewhere, turned my back on this crabbed face and left the hall.

By the time I reached the far end of the adjoining hallway, I was in an extreme state of agitation. I had forgotten all about my connector. To calm myself, I began repeating an old nursery rhyme: While I was going to Saint Ives, I met a man with seven wives. Rivera’s murals had upset me deeply and I thought only of getting away from them. Putting one last corner between myself and the factory, I wheeled smack into a mounted photograph: three young men from the turn of the century stand in a muddy road, looking out over their right shoulders. I knew it at once, though I had never seen it before. How many were going to Saint Ives?

The photo caption touched off a memory: Three farmers on their way to a dance, 1914. The date sufficed to show they were not going to their expected dance. I was not going to my expected dance. We would all be taken blindfolded into a field somewhere in this tortured century and made to dance until we’d had enough. Dance until we dropped.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...