- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

She knows the taste of death. He’ll stoke her hunger for it.

Eighteen-year-old Sarai doesn’t know why someone tried to kill her four years ago, but she does know that her case was closed without justice. Hellbent on vengeance, she returns to the scene of the crime as a Petitor, a prosecutor who can magically detect lies, and is assigned to work with Tetrarch Kadra. Ice-cold and perennially sadistic, Kadra is the most vicious of the four judges who rule the land—and the prime suspect in a string of deaths identical to Sarai’s attempted murder.

Certain of his guilt, Sarai begins a double life: solving cases with Kadra by day and plotting his ruin by night. But Kadra is charming and there’s something alluring about the wrath he wields against the city’s corruption. So when the evidence she finds embroils her in a deadly political battle, Sarai must also fight against her attraction to Kadra—because despite his growing hold on her heart, his voice matches the only memory she has of her assailant…

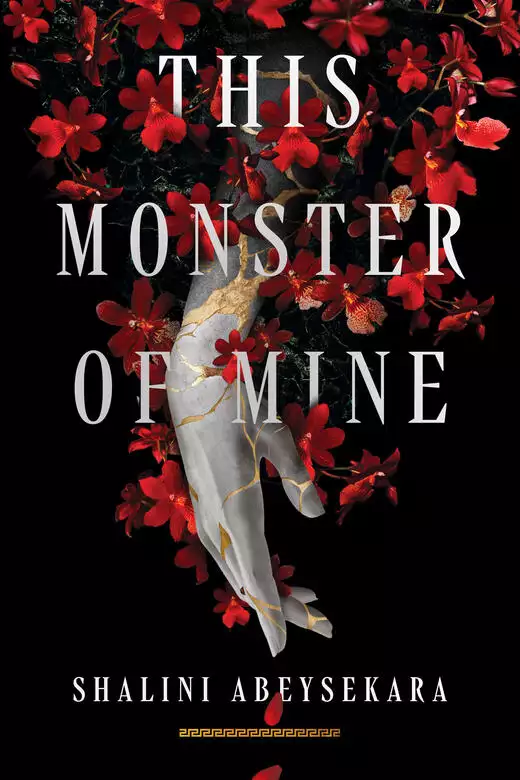

A dazzling Ancient Rome-inspired romantasy debut, This Monster of Mine is a bloodbath of manipulation, deception, and forbidden love.

Release date: April 1, 2025

Publisher: Union Square & Co.

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

This Monster of Mine

Shalini Abeysekara

PROLOGUE

The girl was still alive when he returned with the tablecloth they’d use to dispose of her.

The material slid between his fingers. Honeybee silk, a shroud suited for bluer blood than hers, though she wouldn’t be grateful. A burst of wind swept in from the balcony to dim the sconces ringing the ballroom, but he could still make out the figure on the floor, hear labored breaths quickening as he approached. More corpse than girl, she contorted into a fetal position, clutching what was left of her robes around her thin chest. Lacerations graffitied her breasts and sallow face. Chunks of singed hair littered the floor around her, the remainder melded to her scalp.

His lips pressed together. Not again. After a brief, futile search for patience, he fixed the fool across the room with a stare.

“Five minutes,” he said through clenched teeth. “I left you for five minutes to cut her up for disposal. What in all the hells is this?”

The oaf fidgeted, clutching his arm. A nasty wound bled through his fingers. “It’s a prime piece of flesh.”

There was nothing prime about the body bleeding over the floor, but his business partner wasn’t known for his intelligence.

He spread out the tablecloth. “How did she cut you?”

“She’s a healer,” the fool spat. “Ripped at me when I touched her.”

“Well, she’s weak or she’d have liquefied you, bones and all, wouldn’t she? You’d be a screaming shapeless mass of skin.” He let the suddenly quiet man consider that image. “Pack her up.”

“I didn’t even get to enjoy her,” the fool said mulishly, crouching to ponder the mess he’d made of her. “Might still be able to make it work, though.”

Trying and failing to be surprised that the man could evoke enthusiasm for a half-burnt, half-dead girl, his gaze drifted back to the floor. Her resistance had cost her. The bones of a chair lay fragmented by her skull, a once ornate vase’s ceramic shards studding her skin to leak blood over the tiles. By the Elsar, disposing of her was going to be a headache.

“What I don’t understand is why she was here.” His voice was dangerously quiet. “She’s clearly no illusion magus, and this room is well warded. How did she get in?”

The other man rose, color slowly leeching from his face. “In my defense,” he mumbled, “I couldn’t have known that she was awake.”

Alarm spiked sharp through him. In my defense. The most useless words in the common tongue.

In two strides, he seized the man by his collar. “Explain.”

“I stuffed her in the closet before our meeting, alright? For afterward. I thought she was asleep—” The fool choked, going ruddy as he tightened his grip. “Her wine was drugged! A few sips should have incapacitated her!”

He released him with a barrage of curses. “She pretended to drink it, you havïd fool. They’re smarter these days. They don’t simply swallow what’s offered to them.”

Which meant that she would have been lucid throughout it all. Could have overheard them. Everything he’d worked for could vanish like lightning, and all for one man’s depravity. He’d never liked the fool, but, tonight, he’d happily burn his throat to a crisp. His thoughts must have shown because the other man sidled out of reach.

“By the Elsar, it was a mistake,” the fool croaked. “It won’t happen again—”

“So don’t let it linger,” he hissed. “Carve her up. Now.”

“But I didn’t get to—”

“Do I look like I give a damn about whether or not you got to bed her?”

The fool shrank away. “There’s just one other thing.”

I should just kill him. He waited.

The man looked everywhere but at him. “She’s the one that girl of yours brought.”

He stilled as the words sank in, then lunged across the room. The fool darted to one side, a finger sweeping across a rune on his armilla. A shield of lightning hissed and crackled to life, enveloping him.

Within, he crossed his arms, chin jutting out despite the sweat beading on his temples. “She’s just some northern girl!”

“Some northern girl that my aide valued enough to bring here!” he snarled. “Did she see you with her tonight?” He swore when the man nodded. “What happens when she finds her missing and you were the last person seen with her?”

“We’re handling it, aren’t we?”

We. Of course, it was suddenly his duty to remedy everything. “That’s why you shouldn’t have touched her, you useless fuck!”

Hands fisted, he glowered down at the girl. Her eyes fluttered, consciousness coming in bursts. She had to vanish. She knew too much. But what of his lovely aide? Once the body was found, she would suspect the fool. An unwanted distraction when he had such plans for their future. Throwing her off their trail would—his head snapped up, heartbeat settling back into a placid rhythm.

He smiled. “Drop your shield.”

The other man had the gall to eye him warily before complying. The lightning dissipated with a crack, smoke lingering in the aftermath.

He gathered up the tablecloth. At least they’d spare the silk. “Throw her off the balcony.”

The fool’s jaw dropped. “But that’ll draw even more attention.”

“Precisely. Is it a murder? Suicide? A lovers’ spat gone wrong? Everyone will have a theory. They’ll write us a story.”

“That girl of yours might not buy it.” The man scratched a grizzled cheek. “Is she really that special? She’s pretty if you go for the frail type, but—”

“She’ll buy it,” he said curtly. She always did. Spotting the relief dawning on the man’s face, he snaked out a hand

and gripped the now-bruised flesh of his neck again. “But pull a stunt like this again, and it’ll be you I’m flinging off.”

The fool nodded, eyes watering at the grip. Releasing his throat, he ignored the brief flash of anger across the man’s face. Resentment was the defining characteristic of their alliance. A master and his brainless but powerful dog. They needed each other and resented that knowledge.

The girl twitched as the fool stalked to her. Gripping what was left of her hair, he pulled her toward the balcony, shaking her by the scalp when she struggled. Ceramic slivers clinked as her body carved a path through the broken vase. He watched the man hesitate and sighed.

“There’ll be plenty like her once things get underway, so just throw her off—”

“You’re disgusting.”

He paused at the rasp of sound. Propped against the balcony’s railing, the girl’s eyes defiantly bore into his. He saw in them the knowledge that she was going to die, hatred of him and the fool—all predictable—but the sentiment curving her lips gave him pause. Derision.

“You think you’re clever,” she croaked. “But someone will notice. They’ll wonder why I died.”

He crouched as close to her as he could stomach. Truly, the smell coming off her was horrendous—burnt flesh, sweat, and the copper tang of blood that always soured his stomach.

“People may wonder,” he conceded, inhaling shallowly. “A few might even put it together. But there’s still nothing they can do.”

“The Elsar will damn you for this.” Her voice held pure loathing.

He straightened. “We pray to the same gods, my dear. And given your condition, I’d say they find me more to their liking. But”—he paused consideringly—“we can make certain of that.”

The fool perked up. “You mean—”

A pity. He’d actually tried to spare her this. “We’ve enough time for a little fun. Let’s see if the Elsar make an appearance.”

The other man’s eyes gleamed, one hand already on the hilt of his dagger.

He tilted his head to the girl in farewell as the fool began. Moonlight struck metal. Blood arced over the balcony’s stone tiles—he’d have to have them scoured. Her eyes never left his, terror and rage blotting out all light as she pleaded with the gods and the Saints for salvation. Screaming in desperation, then agony.

He shook his head. Really, she should thank him. By next morning, an unremarkable northern girl would be the talk of Edessa. He was giving her a death so spectacular it would live on in legend.

“The Sidran Tower Girl,” he mused, and smiled as she fell into the shattered moonlight. “Oh yes. That’ll stick."

CHAPTER ONE

Most days, all Sarai saw was blood.

She found it in the crimson wine being tipped into Chieftain Marus’s cup, in the setting sun painting Arsamea’s snowdrifts scarlet. It lurked in the mahogany countertop where a dozen cups perched for her to polish. And tonight, she wasn’t the only one seeing it.

The red-eyed specter of Lord Death seemed to hover in Arsamea’s only tavern, turning the villagers’ smiles a little too wide and their laughs too forced. Everyone except Chieftain Marus, of course. At the head of the table, he slapped his pelt-covered thighs, guffawing uproariously. She stepped out of his line of sight. The more he drank, the harder he hit.

“Last toast of the night!” He thrust his goblet high, spilling half its contents.

Sarai raised an eyebrow. They had been on that “last toast” for some time now.

“To the assessors that seek out our humble town every year!” Marus pronounced. “And to the Tetrarchy. Long may they rule!”

Cups rose and clinked, and Marus promptly poured the other half of the goblet over his face in an attempt to reach his mouth. She turned her snort into a sneeze when Cretus narrowed his rheumy eyes in her direction. Hands braced on the counter, he returned to examining his tavern with predatory intent. His profits would be high tonight. Ur Dinyé’s most remote village had so little to celebrate that the assessors’ visits from the capital had become a strange annual festival. Where everyone toasted the misfortune of those assessed as a Petitor Candidate. Where they thanked the gods, High and Dark, that it wasn’t their kin being bundled away to Edessa to be trained for four years at exorbitant tuition fees, only to take their lives after graduating.

That was Arsamea. Grateful for what they had and grateful that others lacked the same. And at present, everyone was grateful that they weren’t Chieftain Marus.

“Feels like yesterday when Cisuré started at the Academiae, and she’s already graduating,” Marus boasted to a silver-haired man whose smile looked frozen on. “One month and she’ll be a Tetrarch’s Petitor.”

“You aren’t … worried?” the man ventured, causing several others at the table to stiffen.

Marus waved a hand. “She’s mountain bred. None of that city-folk weakness in her. She’ll handle the job.”

For once, Sarai wanted him to be right. She couldn’t lose Cisuré on top of everything else, and their letters, brief and stilted as they could be, were one of her few tethers to hope.

A few years back, this unease around Petitors would have been unheard of. They were highly prized for their rare brand of magic: detecting lies and tunneling into the memories of those accused of crimes to extract evidence during trials for public view. A talent so indispensable to governance that assessors scoured Ur Dinyé for Candidates and trained them at the land’s most prestigious school. Graduates all received lifelong posts with government officials, with the very best getting to work for the Tetrarchy, the land’s ruling judges. Then, four years ago, the Tetrarchy’s Petitors had begun taking their lives. Now, Candidates were highly prized for a different reason.

“Word is that there’s only a few Candidates left in the Academiae. The rest all fled Edessa.” Ethra, the town’s new healer—and Marus’s bit on the side—pursed her lips. “Imagine running from serving a Tetrarch.”

“The job’s cursed,” Flavia, Arsamea’s oldest resident, pronounced. “Don’t the Codices warn of the forbidden realms of the dead and their lust for resurrection? Something haunts the Tetrarchy. On Wisdom, I feel it.”

Sarai hid a snort when the table agreed in hushed whispers. This was why southern Urds classified everyone from the north as backward, largely magicless mountain swine. Yet, sometimes, she wondered if Flavia had a point. The Tetrarchy had hidden the conditions of their dead Petitors’ corpses, but the capital’s grapevine had unearthed and passed on murmurs of sliced limbs, self-immolation, and daggers shoved to the hilt in throats, all of which had raised the same questions across the country. Why would a Petitor take their life with such brutality?

And here I am pining for the same job. Sighing, she picked up another cup to polish. No hope yet, whispered the meager coins in the pouch around her neck. Not for a long time. Because it didn’t matter that she possessed the magic the assessors sought. She couldn’t afford a year of the Academiae’s tuition, let alone the requisite four; and until she could, she wasn’t a Candidate. She was nothing.

“Must be nice in the capital.” Ethra gloomily stared at the snow piling outside. “Imagine all that sun and sand on our—your skin,” she corrected, after a glare from Marus’s wife.

Sarai warily eyed the two women’s tight grip on their utensils. Their last fight had ended in her scrubbing the floor for hours to prize off the deer gizzards they’d thrown at each other.

Oblivious to the fact that he was the root of most of the village’s problems, Marus shot Ethra an irritated glance. “Nothing wrong with our life here.”

“It can be a little dull,” she foolishly persisted, looking around the table for support. “Haven’t you wondered if the south might have more to offer?”

The table fell quiet. Clouds gathered on Marus’s face. Now she’s done it.

He rose with the menace of a blackstripe bear. “Run off to Edessa then. Or have you forgotten what happened to the last brainless woman who did that?” He jabbed a finger that, even in his drunken state, unerringly found Sarai.

She stilled. Anger, always so close at hand, welled forth like blood as heads swiveled toward her from across the tavern, sporting matching expressions of glee. Reminding her that she was worse than nothing because nothing received merciful indifference. She silently prayed to all seven of the High Elsar that the barb was a one-off. Then again, the gods had never been overly fond of her.

Booted steps approached the countertop. Marus tossed his cup at her, spite on his red-splotched face. Emptying half an amphora into his cup, she returned it to him. Don’t do it, Marus. Leave me alone.

“That’s what stupid ideas get you,” he told Ethra, prodding the air by Sarai’s face to indicate the ridged scars mapping

every inch of her, brown tributaries within golden skin. “Still think the south has anything to offer?”

Sarai’s nails formed red crescents in her palms as Ethra shook her head with distaste. Stupid ideas. As though her scars were a punishment from the gods. She had no insight into whether the Elsar gave a havïd that she’d dared to be orphaned in a town that froze over for nine months of the year, or that she’d been desperate enough for education to leave Arsamea four years ago and follow Cisuré to the capital. But the good townsfolk certo did. So when she’d returned as a scarred wreck after only three days in Edessa, they had never let her live it down.

Perhaps the scars were punishment for the day she finally poisoned them all.

Marus snorted when she forced herself to placidly polish another cup. “If Cretus didn’t need the help, I wouldn’t have allowed you back, scum. So certain you were too good for us, only to crawl back as a patchwork creature. The Academiae didn’t want the likes of you, and Cisuré had no use for you at all.”

At least the second half wasn’t true. Your daughter writes to me every month, asshole.

“Four years,” Marus told his rapt audience. “Cisuré’s soon to be a Petitor, and this one’s still a barmaid. Blood will out. The worthy will rise, but the rest? Destined for dirt.” He seized her jaw. “Though someone already taught you that lesson, didn’t they?”

A shudder ripped through her at his touch. Crimson tainted her vision, bitterly familiar. She bit her cheek as the walls pressed closer, the room tilting and rippling while the warm salt of blood filled her mouth. Just as it had that night in Edessa when her body had smashed into the ground, blood pouring from shattered limbs, as someone crouched over her and—

Marus released his grip, shoving her head back. She collided with the wall, nearly knocking over a row of amphorae. The cup she had been polishing clattered to the ground as laughter erupted from every corner of the tavern.

“Did you see her face?” someone yelled. “Where’d you go, Sarai? Back to Edessa?”

“Maybe get another new nose while you’re there,” another hooted.

Trapping her tongue between her teeth, she picked up the fallen cup and braced herself for another blow. Marus’s fist rose right as an ear-splitting cheer went up outside. Past the window, a stampede of Arsameans launched themselves onto the snowy streets.

“The assessors are here!” a passerby yelled. “Drag your sotted selves out!”

Thank the High Elsar.

Sparing her an ugly glance, Marus raced out the door. Chairs scraped across stone as the town’s fairest and finest elbowed past each other to parade behind the magi. A mismatched assortment of bells chimed in chorus, dull peals mingling with the deep boom of a gong that some enterprising villager must have dug out of the cellar. It was nothing she hadn’t seen before, and tonight would be no different. She’d man the tavern, manage the raucous magi and their helpers who showed up expecting Arsamean women to do anything to please them—and wonder if she’d ever have enough coin to leave this glacial hellhole.

Snow swirled through the open doorway, ice clinging to threadlike fissures in the tavern’s stone walls. Rubbing the shoulders of her thin tunic, she straightened the chairs and collected the grease-covered plates left on the tables.

“Tunnel rat.” Cretus hobbled over, holding out a wrinkled palm. “You still owe a denarius for this month’s rent.”

She frowned. “I’ve paid my two denarii.”

“Rent’s gone up.” He stuck a finger in his ear and dug for something. She hoped whatever it was tunneled all the way to his brain.

They’d played this game before. As the only person in Arsamea who’d house and employ her, he meddled with her rent and wages as he saw fit. And every time, he would seek a reaction.

Cretus snapped his fingers, beady eyes slitted. “Deaf now? You paying or moving out? Plenty who’d take your room.”

It’s a fucking storage shed. She held back the urge to snap his wizened wrist. “I’ll pay.”

His mouth pulled back in a triumphant smile. “Keep everyone drunk tonight. I want an accounting of every bottle sold. And for the Elsar’s sakes, duck your head while serving, or you’ll put the assessors off dinner.”

With that, he dragged his hood over the wisps of hair valiantly clinging to his scalp, and plodded toward the outhouse.

She saluted his back with a middle finger, then sank onto the nearest chair.

Cretus paid her one bronze assarius a day. With rent going up, she’d have to miss meals to maintain her current rate of saving. Sarai quashed the ache in her stomach warning her that she ate too little as is. Four years ago, she had felt life drain from her with every agonized breath. Had barely survived, only to be thrown out of Edessa without justice and left with no recourse but to save coin after coin serving wine, while the man who’d destroyed her body, her hands—her life—ran free. Hunger held little weight in comparison.

Unknotting the coin pouch from her neck, she spilled her savings onto the drink-spattered table. Firelight winked off three gold aurei and five silver denarii. Not enough. It would take years for her to afford the Academiae’s tuition. But only Petitors and Tetrarchs could access sealed case records. And somewhere in sun-drenched Edessa, within the restricted Hall of Records, was a wax-sealed scroll bearing her name. Victim. Beside it would be a single charge—attempted murder—and details of the night she couldn’t remember four years, three months, and twenty-eight days ago. Details someone had wanted hidden. And somewhere in that same city lurked her assailant. Becoming a Petitor was her best chance at revenge.

Once she could afford the Academiae’s tuition at least.

Sighing, Sarai scraped the coins off the table. “I hope at least you’re doing well, Cisuré.”

For a moment, she could almost see the other girl sitting across from her with a blinding smile, enthusing over a new bit of frippery, or sobbing into her shoulder after Marus had beaten her for yet another imagined show of defiance. But that had all been four years ago, before Cisuré had become a Candidate and the Fall had made vengeance Sarai’s master. Before they’d discovered that even friendship couldn’t entirely bridge some divides.

Swallowing, she rose and halted at a movement past the snow-streaked window. A figure stealthily emerged from the shadow of Cretus’s smoke chamber for wine, lugging an amphora behind her.

Havïd. Sarai snatched her birrus from behind the counter, locked the door, and raced outside into a blast of icy wind. Cursing roundly, she covered the scant yards to the fumarium and shoved both the girl and the amphora into a snowdrift, just as Cretus emerged from the outhouse. She ignored the wine-thief’s annoyed squeak, waiting until he’d faded to a thumb-sized speck in the direction of the town square before releasing her grip to scowl at the sputtering girl.

“I thought we’d agreed that you’d stop.”

Vela brushed snow from her closely-cropped dark hair. “Coin’s got to come from somewhere. Cretus can afford the loss.”

“You can’t afford being caught. He’ll whip the blood out of you.”

“The last time Cretus moved faster than an inch a minute was when Marus was in swaddling furs.”

Sarai’s lips flattened. “He sliced off another tunnel rat’s fingers only two weeks ago for pocketing a loaf off the counter.” The boy had met her eyes with knowledge of his fate—infection, fever, which would become sepsis without a healer, and a delirious, prolonged end. Before the Fall, she might have been able to heal him. Now, her hands were too ruined to save anyone.

Undaunted, Vela shrugged. “The boy was careless. I’m—”

“Clearly as bad, because I saw you. Wrath and Ruin, if there was a drunk asshole around, he’d break your hands if it meant getting his on this.” She took the amphora from her. “There are worse things in life than Cretus’s retribution.”

“I know.” The twin moons lit Vela’s wince as her gaze darted away from Sarai’s scarred features.

Pretending not to notice, her grip tightened around the amphora, a ruby-red drop leaking past the loosened seal to hit the ground. Blood on ice.

Sarai looked away. “Where are you selling it?”

“Sal Flumen.” Vela fell into step beside her.

“You’re mad.” It was a fifteen-day walk. She’d attempted it once and nearly died of cold.

“I’ll survive.” The younger girl set her jaw. “I’m staying there for good. Havïd to this village.”

“Agreed.”

A few minutes south of the tavern, they stopped before a depression in the snow. Vela tapped her boot over it in a series of metallic thuds, and the trapdoor to Arsamea’s tunnels swung up. Centuries-old relics of Ur Dinyé’s wars, they ran under the village and through the mountain, though no one dared venture that deep. A bedraggled girl waited atop the ladder leading down. No more than eight winters, she stared at the amphora, all hollow eyes and cheeks.

“Guard it, and I’ll bring you dinner, Elise,” Vela promised.

Sarai reluctantly relinquished the amphora when Elise held out her hands, wincing when the girl staggered at the weight. But assisting her would only make Sarai a target. The folk in those tunnels would gladly rip the pouch from her neck and divide her savings just as they had done to many others. She knew their ravenous hunger well. The tunnels were her birthplace, and where her parents had met their end in an ibez-smuggling run gone wrong, leaving her with misshapen memories of gaunt faces and what could have been a mother’s smile or a drunken grimace. Cretus had plucked her out at seven when searching for exploitable labor, because she’d been small enough to harvest snowgrapes from their thick, brambly vines. She’d been lucky. Those tunnels held more corpses than people.

“Any other children this winter?”

Vela closed the trapdoor with a clang and followed as Sarai turned back to the tavern. “Just Elise. Parents lost everything at a gambling house and crawled down with her. They’re long dead.”

Damn it. Pretending to adjust her birrus, Sarai discreetly withdrew a silver denarius and shoved it at her. It’s fine. She was nowhere close to affording the Academiae’s tuition anyway. Vela’s eyes widened as she took it.

“Take Elise with you.” Sarai tamped down all regret as the coin left her fingers. “When are you leaving?”

“Tomorrow morning, while everyone’s wasted in bed. Might even steal a horse.” Vela’s grin faded. “You don’t have to keep looking out for any of us, you know. It’ll confuse Elise into thinking that people are decent. Still confuses me.”

“Tell her that the coin is yours. In Sal Flumen, pretend to be middle-class siblings whose parents were attacked by brigands. Pity and a child in tow might get you far.”

“Brilliant.” Vela marveled at the denarius, flipping it between her knuckles. “You sure you don’t want to leave Cretus to rot and join us?”

The thought was always compelling, like spun sugar on her tongue until reality dissolved it.

She feigned a laugh. “The rent’s twice as high, and I can’t compete with the fabri. They’ll say I’m too old for any profession but pleasure-work.” The irony was that Arsamea was the safest place for her until she had enough for tuition. She knew the villagers’ habits. In any other northern tavern, she could suffer much worse than Marus’s fist.

“Must be warm.” Vela stared longingly at the golden glow emanating from the town square at the end of the street. Raucous cheers carried on the wind. “Do you think they ever wonder if we’re cold?”

“They don’t think about us at all.” Sarai eyed the snow-mottled furs strewn on the street in a semblance of a carpet for the assessors, while people froze to death in the tunnels only yards away. “So you shouldn’t think about them. If they poisoned us all tomorrow, no one would care.”

Wind shoved at their backs. Both moons hovered above, silver Praefa melding with Silun’s bluish incandescence to cast the town in a sepulchral glow. A moonbright night—both orbs near full but never full together, ordained by the gods to wax and wane at different intervals. Perhaps her dreams were the same, destined to never intersect with her.

A sharp rap snapped her out of self-pity. Squinting at the tavern, a frisson of worry ran through her at the violet-robed figure silhouetted at the door. What in havïd is an assessor doing away from the square?

He knocked again. “Anyone inside?”

Sarai sighed. “I’d best go get his drink.”

Vela nodded, staring at her feet. “Well … goodbye then.”

Sarai managed a smile. “I’m glad you’re getting out of here. Steal that horse tonight. There’s a snowgale in

“I’m glad you’re getting out of here. Steal that horse tonight. There’s a snowgale in the air.”

The younger girl sniffed the wind and scowled. “Damn. I’ll leave now then. I’ll try to send some fruit on the next merchant wagon.”

“Save your coin and eat well instead—” Sarai grunted when Vela threw her arms around her. Letting go just as quickly, the other girl stuffed her hands in her pockets and bobbed her head awkwardly before racing in the direction of the stables.

Live well, Vela. The ache in Sarai’s stomach rose to her chest. Envy, yearning, happiness for the other girl. She let it fester, grow tendrils that sank all the way to her threadbare boots. Then, the cold seeped in and killed the roots, the buds, the ache.

Glancing at the annoyed magus banging on the tavern door, she returned to her frozen life.

Sidling in through the back door, Sarai peered at the assessor framed in the window.

“One moment!” she called, crouching behind the counter and fishing in her pockets for her armilla.

Engraved with the user’s runes of choice, the white-gold bracelets were a magus’s preferred way to access dormant magic—much tidier than the alternative, bloodletting and drawing runes with the blood. She prized out the pin slotted into the bracelet’s bulky hinge, pricked a fingertip, and smeared the blood over nihumb, the rune for “concealment.” Silver flashed in the rune’s deep grooves, a corresponding lurch tugging within her chest. The deep brown scars wrapping her blurred, then faded into her skin. An illusion discernible by touch, a secret she’d kept from the townsfolk, and a skill she’d nurtured in the event she ever saved up enough for tuition. She’d never used it in public before. Contrary to Cretus’s certainty that her face was bad for business, the assessors were usually too deep in their cups to care about how mangled the barmaid was. But he was early, and she was alone, and despite her features having been altered during reconstruction, her scars were a rarity, evidence that even multiple healers had been unable to fully restore her. They made her recognizable. And there was always the risk that one of these assessors could be him.

Unlocking the door, she bowed. “Welcome to Arsamea. I’m Sarai. A pleasure to serve you, Magus …?”

“Telmar.” He swept past her in a whirl of violet robes and collapsed into a chair, snow sliding off his shoulders. “Icewine. And shut the godsdamned door before I freeze to death.”

Judging by the magus’s bloodshot eyes, he was more in danger of pickling himself in drink. Nevertheless, Telmar seemed lucid enough to survey her as she brought out an amphora of Cretus’s best icewine.

“Sit.” He imperiously gestured at the chair beside him once she’d filled his cup.

“Apologies, Magus Telmar, but my place is behind the counter.”

He gave her a disdainful look. “By the Elsar, you hicks bore me to tears. Off to your counter then. Like there’s anyone else for you to serve. They’re all busy listening to the same speech year after year.” He affected a sonorous voice. “Every year, our courts accumulate defendants requiring a Petitor’s aid. Some need to be Examined, their truths distinguished from falsehoods, and—”

“Others must be Probed and their memories Materialized in public for assessment,” Sarai finished, and the magus snapped his fingers.

“See? You should deliver it next year. I’m tired of shaking hands and being praised like I’m one of the Elsar. You lot reek.”

He doesn’t seem out for lechery. She sat across from him. “How’s the search for Candidates going?”

Telmar gave her a look that could have been appraising. His eyes merely twitched in his skull. “What do you think? Like Petitors offing themselves in every godsforsaken way for the past few years wouldn’t dampen things.”

“What about borrowing some from other cities?”

He snorted. “No chance. No Praetor or Tribune will relinquish them, and Petitors who would’ve killed to serve a Tetrarch won’t go near one now. They’d rather be bound to a no-name town official than turn corpse in Edessa. Only three Candidates from this year’s graduating class haven’t scarpered, and they’re being watched in case they try.”

“Cisuré’s one of the three, isn’t she?” At Telmar’s confused squint, Sarai elaborated. “Pale hair, dark eyes. Memory like a bear trap.”

“Oh yes. Taught her to handle a sword last year.” He chuckled at her unamused stare. “Mind out of the gutter, barmaid. I meant that literally. She was terrible with a blade. Wouldn’t be surprised if she’s the first to die.”

“Don’t say that,” she grit out."

Telmar flapped a hand in dismissal. “Well, she’s graduating. Time for her to be bound to an official, and there are no vacancies anywhere but the Tetrarchy. Her father sounds right proud.”

And Sarai had nearly taken refuge in Marus’s certainty. But here was an assessor, an instructor at the Academiae, musing that Cisuré was poised to die.

The wall enclosing her scant memories of that night shuddered. She drew slow lungfuls of air, but it wasn’t enough. Every breath brought back a sound, a sliver of memory from her journey to Edessa four years ago. Squeezing into a fruit seller’s wagon with only two goals: to follow Cisuré to Edessa and become a healer so renowned that no one could look down on her. Jumping off the wagon, ready to forge forward, and … blood. Rain. A wet crack as her body hit the cobblestones. Splinters of her ribs shoving through her lungs—

Her fist hit the table. Telmar gave her a wary look. “Do all the Petitors die every year?”

“Depends. When one dies, the rest get spooked and flee. But last year, they all died.” He laughed into his cup. “And we still trundle to every corner of Ur Dinyé, seeking more victims.”

“But other officials’ Petitors are alive and well! Why are only the Tetrarchy’s ones killing themselves?”

Telmar’s glazed eyes shuttered. “There’s nothing we can do.” Dipping a finger in his wine, he stirred it and flicked the excess all over the table. “You serve wine, and I hunt for souls to throw into the job. It’s on them to survive.”

Wait. Her head jerked up. “Throw into the job? What happened to four years of training?”

He scratched his short beard. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...