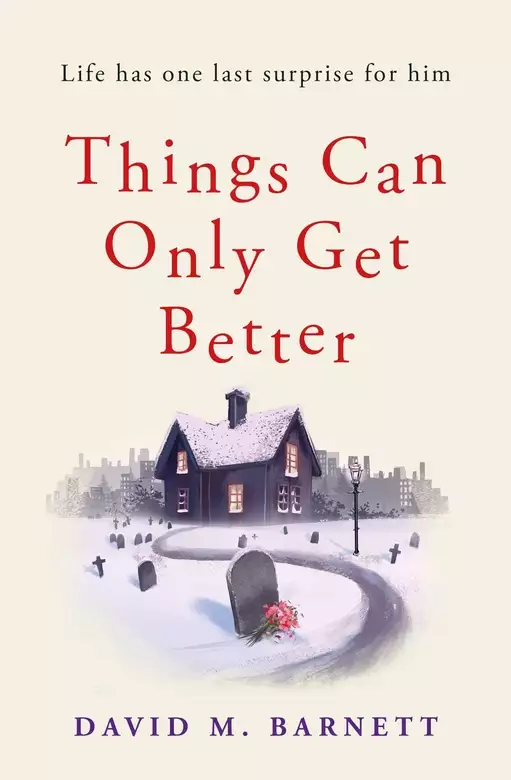

Things Can Only Get Better

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

*FROM THE INTERNATIONALLY BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF CALLING MAJOR TOM*

For elderly churchwarden Arthur Calderbank, there’s no place like home. His home just so happens to be a graveyard.

He keeps himself to himself, gets on with his job, and visits his wife everyday for a chat. When one day he finds someone else has been to see his wife – and has left flowers on her grave – he is determined to solve the mystery of who and why. He receives unlikely help from a group of teenage girls determined to break out of the poverty trap by emulating their Britpop heroes and forming a band, and as Arthur and the girls try to find answers, he soon learns that there is more to life than being surrounded by death.

Set when we were all common people and things could only get better, this is an uplifting story about the power of a little kindness, friendship and community, for readers who enjoy Sue Townsend, Ruth Hogan and Joanna Cannon.

Release date: November 14, 2019

Publisher: Trapeze

Print pages: 325

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Things Can Only Get Better

David M. Barnett

The chapel that sits at the centre of the graveyard has been subdivided by stud walls to provide Arthur with a bedroom and a living area. There was already a small kitchen and a washroom, which have been complemented with the addition of a microwave and a shower cubicle. Arthur did all the work himself. Always been good with his hands. It is spartan, and bare, and as far as it is possible to be in terms of comfort and cosiness from the house he shared with Molly for all those happy years. But it is, for better or worse, home. After a fashion.

Some of the old pews Arthur has arranged as storage or seating around the edges of his living space; he’s made a serviceable table from the timber of three of them, with more pews along either side. The rest he’s broken up and keeps in a woodstore he’s built at the back of the chapel. He has electricity, but no gas, and warms the place with a wood-burning stove on which he sometimes also cooks. This morning he has a pot of porridge on the go. Through the tall windows he can see that the cemetery is carpeted in snow, luminous in the moonlight. Definitely a porridge morning. He sits by the stove, rubbing feeling into his hands. They’ve been muttering that he’s getting too old for this, that he should be somewhere warmer, safer. And it’s true, he does feel the cold more now. It takes him longer to get moving in the mornings, especially mornings like this. But while he’s no spring chicken – he’ll be seventy-two next birthday – neither is he ready for the knacker’s yard just yet.

Giving the porridge a stir, Arthur stretches his legs and pads across the wooden floorboards, unsure if the creaking is the old timbers or his old joints. His calendar hangs from a nail by the bookshelf (made, of course, from another old pew). December the fifth already. He takes up the felt-tip pen from the bookshelf and puts a firm cross through the number 4. He never strikes out a day until he’s woken up on the next one. Bit of a superstition, he supposes. Tempting fate. Strike out a day too early, and maybe you’re saying your time is up, maybe you’re saying take me now. Arthur shakes his head. Silly old sod. He never used to be superstitious, never had the time. Perhaps he has been living here, on his own, too long.

At the tall windows – the stained-glass originals had long since been broken or stolen and replaced with cheap, plain panes that rattle in the wind – Arthur looks out on the snow-covered graveyard which spreads out all around the chapel. The headstones are frosted like ornaments on a cake. He glances over his shoulder at the calendar, at the thick, felt-tip ring around the number 23. Old, he thinks, turning back to the window, there’s no denying that. But never alone.

‘Filthy morning, Fred,’ says Arthur. He looks to the sky, and tuts. ‘Don’t think this snow’s going to let up all day. Might be in for the week, according to Michael Fish. Then again, he told us we weren’t going to have that hurricane about ten years back, and you remember how that turned out.’

With his gloved hand, Arthur absently clears the crisp snow from the top of the nearest headstone, then laughs. ‘What am I talking about, Fred? You’d been in your grave for five years when that hurricane happened.’

Arthur moves along the ranks of graves, wiping snow from the stones, though there’s not much point. Thick flakes dance from the grey sky, filling his footprints and piling up on the headstones again. He rights a metal pot filled with the desiccated husks of chrysanthemums at Mabel Shepherd’s grave, and frowns at Don Gaskell’s marble headstone, which is leaning at an angle. Arthur pushes the stone lightly and it moves another inch. That’ll need resetting. He should probably call the council, but it’ll be quicker to just do it himself. He’ll have to wait until the ground’s not so frozen, though.

Near the back wall of the cemetery, which borders the site of the old pit where he used to work what feels like a lifetime ago, Arthur sets to at a mass of dead brambles with his big secateurs, piling the thorny twigs up against the black stone. Not many folk come down to this bit of the cemetery these days, but that doesn’t mean he has to let standards slip. Some of the headstones are so old that the names and dates on them have faded into indecipherable hieroglyphics. A little further down, towards the corner of the wall, there are a jumble of proper old mausoleums and walled graves, which no one ever visits at all. When he’s cleared as much of the brambles back as he thinks makes the place look respectable, Arthur ties the cut pieces with twine, and wraps them in a length of hessian sack. He’ll dry those out and burn them on his stove.

He pauses at the grave of Noah Jones. First resident of the cemetery, buried the day it opened on August 17, 1803. Son of one of the town’s biggest cotton merchants, died of tuberculosis when he was nine. What must it have been like for his parents to lose a kiddie, Arthur wonders? What must it have been like to have children in the first place?

‘Bet you loved the snow, didn’t you, Noah?’ murmurs Arthur. ‘Bet your dad bought you a sledge, with polished runners. I bet it flew, didn’t it, Noah? Bet you screamed when you went down the hills, half in terror, half in laughter.’

Nine. No age to go. But not uncommon back then, even if you had money like Noah’s family. Somebody once asked Arthur if it was scary living in a cemetery, if he was worried about ghosts. Not superstitious, not Arthur Calderbank. Didn’t believe in tattered shrouds and rattling chains. But he did sometimes wonder … what if there were ghosts? He thinks what it would have been like for little Noah, first person buried in the cemetery, wondering where he was and where everyone else had gone. Now, he ponders what it must be like, if they all stretch and yawn and get out of their graves just as Arthur stretches and yawns and climbs into his bed. He pictures Don Gaskell telling Noah off for running around, Mabel Shepherd telling Gaskell not to be a nowty old sod, and Fred Ormerod asking Mabel if she’d like a dance around the mausoleums.

‘Silly old bugger,’ says Arthur to himself, shaking his head. The dead don’t get up, and dance and scold each other. If only they would.

Before heading back into the chapel, Arthur stops at Molly’s grave for the first time that day. It won’t be the last time. He wipes the snow from her stone and with his gloved finger pushes the crystals of ice from the indentations of her carved name.

‘Nearly Christmas, love,’ he says softly. ‘Nearly your birthday.’

Arthur takes a handful of the green glass chips that cover Molly’s grave and squeezes the snow from them. ‘Just been clearing some of the brambles back from the old bit,’ he says, conversationally. ‘I know nobody goes down there any more, but they’ve got vicious spikes on them. Could hurt a kiddie, if one wandered over.’ Letting the glass chips fall from his hand, Arthur takes a rag from his coat pocket and starts to give Molly’s stone a proper wipe down. ‘I’m going to have to look at the wall near the top of Cemetery Road later as well. You know, where that bloody idiot boy racer smashed into it last week. Council’s highways mob reckon they’ve made it safe but I don’t like the way the capstones are sitting.’ He pauses, imagining what Molly would say. ‘Of course I’ll be careful,’ he says. ‘I know I’m not as young as I was, don’t worry.’

Arthur runs the cloth across the top of the gravestone again, but he knows he’s fighting a losing battle against the snowfall. It feels like only five minutes since he had his porridge but his stomach’s rumbling again. ‘I’ll look at it after my dinner. What do you think I should have? Got a bit of that ham left. Could make a sandwich.’

He knows what Molly would say. You need something warm inside you, day like this. Not a butty. ‘I suppose you’re right. Again. You’re always right, love. But what, though?’

‘How about a pie?’

‘Jesus Christ!’ yells Arthur, spinning around. It’s that lad, the thin one with the big glasses and curly hair. Timmy Leigh. He’s standing there, holding something wrapped in a carrier bag out in front of him, his eyes wide at Arthur’s outburst. He takes a step back.

Arthur clutches his chest. ‘Christ, lad, you nearly gave me a heart attack, creeping up on me like that.’

Timmy’s Adam’s apple bobs and his lips wobble. ‘My mum sent me with a pie.’

Always sending stuff, was Carol Leigh. Cakes. Gloves. Books. Sent him a CD once: Glen Campbell’s greatest hits. Arthur didn’t know what to do with it. He didn’t have a CD player and had never liked Glen Campbell. He ended up using it as a coaster.

A pie, though, that’s a different matter. Arthur takes the warm plate wrapped in a tea towel out of the carrier bag and sniffs at it. His stomach rumbles more loudly. ‘Tell your mum thanks, and I’ll send the plate back,’ says Arthur.

‘She said you can keep it,’ says Timmy. ‘And the tea towel.’ The boy blinks owlishly at him and then says, ‘It’s from Pwllheli.’

‘The pie?’ frowns Arthur. Wales was a long way to go for a pie.

‘The tea towel,’ says Timmy. He stares at his feet then says. ‘I have to go.’

‘Shouldn’t you be at school?’ says Arthur, suddenly realising the time.

‘I’ve got a bug,’ says Timmy. He winds his scarf – Arthur recognises it as his mother’s handiwork – tighter around his neck, smiles wanly, and turns to lope with his ungainly stride back along the paths towards the big wrought-iron gates at the cemetery entrance.

Arthur wraps the tea towel tighter around the plate and has one more wipe of the snow from Molly’s headstone. ‘Pie it is, then,’ he says to her, then heads back to the chapel. He’ll do the wall in the afternoon, clear some of the paths of the worst of the snow, then think about his tea. Maybe the pie will do for both. Then a bit of radio, and bed, and another early start. He wonders what tomorrow will bring. He hopes it’s another pie.

Arthur turns and inspects the graveyard. Or maybe it’ll bring something else. Maybe not tomorrow, but soon. He’s out there, somewhere, Arthur knows. Maybe not in the graveyard, maybe not just yet. But he’s on his way. He’s getting closer. Every year he’s been. Every year, on Molly’s birthday, 23 December. Every year since she died. Arthur doesn’t know who he is, he doesn’t know how he does it without being seen, and he doesn’t know why he does it in the first place. All he knows is one thing.

This is the year he’s going to catch the bugger.

Nicola has three papers to deliver on Cemetery Road. Her last three. She pauses at the top of the avenue, one foot on the pavement an inch-deep in fresh snow, her other resting on the pedal of her dad’s old racer. Come on, she thinks. No time to dawdle. Need to be home before mum’s awake.

Nicola hates Cemetery Road, especially on mornings like this. Her breath fogs in the still air, her fingers cold even inside her knitted gloves. Her glasses steam up. There are no lights on in the terraced houses that stretch down all along the left-hand side, dark windows looking blankly over the road and the soot-blackened stone wall of the graveyard that gives the street its name.

She glances over to where the three-quarters-full moon illuminates the cemetery, reflected by untouched, virgin snow that makes the gravel paths indistinguishable from the ordered lawns and carefully-ranked graves. White ribbons cap the headstones and the perimeter wall, and snow lies evenly on the sloping slate roof of the old chapel that crouches blackly at the centre of the graveyard. There is a light on in the old chapel.

There is always a light on in the old chapel.

Nicola tugs off her glove with her teeth and pulls back the sleeve of her coat, exposing her watch. She pushes at the button that casts a pale, weak light over the digital display. Seven-twenty-eight. She is a bit behind schedule, because the snow has made for slow going on her route. But three more papers and she can be home in twenty minutes, enough time for a bowl of Ready Brek and to get into her school uniform, get her sandwich out of the fridge and find her books, and be out of the house before her mum … well. Before her mum no doubt has one of her mornings, which will turn into one of her days. It’ll all be there waiting for Nicola when she gets home, but she’d rather face it at the end of the day than before school.

Nicola digs into the Day-Glo yellow vinyl bag slung over her shoulder, her fingers finding the Guardian. On summer days, if she gets up early enough, she sometimes does her round on foot so she can read the papers before she pushes them through people’s letter boxes. There never seems to be the same urgency to get home quickly in summer. Mum’s never as bad when the sun’s shining. It’s the dark mornings when she’s worst.

Nicola likes the Guardian best, she thinks. One time, Cliff in the paper shop had put an extra one in by mistake and Nicola had taken it home rather than going back to the shop with it. She’d read it all, the news, the features, the business pages. Some of it was a lot funnier than she’d thought it would be. It was a bit harder to understand than the Sun or the Star, but Nicola sometimes looks at them too before she posts them through. Not always for the articles. She sometimes looks critically for a long time at Page Three, at the beaming smiles but slightly empty, vacant eyes of the models, pushing their bare breasts forward. Sometimes she will try to stand like they do, chests thrust out, lips pouting. It is uncomfortable. Mostly it is uncomfortable being a girl full stop, thinks Nicola.

The Guardian is for number five. All the houses on Cemetery Road have small gardens at the front, and number five’s is always choked with weeds, which even now poke up defiantly through the snow. The curtains are always closed, even in summer, and in the bottom left corner of the window is a sun-faded Coal Not Dole sticker. The letter box is loose and flaps about on windy days. Nicola glances at the front page – something about the new Labour leader, Tony Blair – then folds the newspaper twice and pushes it through the flap, listening to it slap on the mat.

The next delivery is for number nineteen, halfway down. Nicola coasts along the pavement on her bike, her thin tyres leaving a narrow groove in the snow. Propping her bike against the garden wall, she fiddles with the catch on the gate, which is always tight and freezes up in low temperatures, every time. Number nineteen takes the Sun. It has the same picture of Tony Blair on the front, but a story that seems to be the exact opposite of the one in the Guardian. Nicola can’t be bothered turning the pages with her frozen fingers just to look at Page Three, so rolls up the paper and eases it through the letter box. This is a vertical one, which she has an inexplicable hatred of. There is no real reason they should be any different to a horizontal one, but they just are. Nicola can’t see why you’d have a vertical letter box instead of a horizontal one. It’s just wrong. Number nineteen already has a plastic Christmas wreath hanging from a nail on the door, which makes getting the Sun through the stupid letter box even more difficult.

One paper left. She knows without looking it is the Daily Express. For number forty-three. Right at the end of the street, the last house on the left. Isn’t that a horror video? She’s seen it on the racks in Blockbuster. Nicola shivers as she climbs onto her bike, and can’t help glancing over towards the cemetery. It looks a bit eerie, the snow almost glowing under the bright moon, the blackened stumps of headstones poking through like breakwaters at the seaside.

Beyond number forty-three is darkness, a bridge over the railway line that leads to an expanse of scrubland and murky ponds, grassed slag heaps chewed up by motorbike scramblers, tangles of high bushes threaded with paths always dotted with dog muck. The site of the old colliery, filled and levelled and landscaped a decade earlier, patiently waiting for someone to come and build a housing estate or a retail park on it, but the weather-faded advertising hoardings proclaiming its suitability and prime location are all but rotted away.

Far behind her a car gingerly negotiates the slush-covered main road which Cemetery Road opens onto, and the whisper of its tyres, even as it disappears from view, gives her some kind of comfort. It is easy to imagine on these dark midwinter mornings that she is alone in the world, that the ever-present nightmares which undoubtedly haunt her mum right now, have her whimpering in the tangle of her duvet, have somehow come true. That the world has ended.

Nicola rides down to the end of the road, peering into the darkness that looms beyond the bridge. She always thinks there are ghosts in that darkness. Ghosts of the men who’d lost their lives during the frequent pit collapses, those who’d lost their pride when it closed down and took the prospects for work with it. Hurriedly, Nicola lets her racer fall into the snow and bounds up the path, hoping that this morning, this morning, this morning it will be different.

But the door, obviously on the latch, swings open even as she presses the Express against the letter box. The woman is there, in her dirty pink dressing gown, rollers in her wispy grey hair, toothlessly chewing her own tongue. Nicola feels her heart sink.

‘Come in for a cup of tea,’ demands the old woman, squinting at Nicola in the darkness. There is the smell of stale cabbage and a smoking coal fire that lingers around her like a perfume.

‘I can’t,’ says Nicola, thrusting the newspaper into her hands. ‘I have to get home for my mum. She’s not well. Then I have to go to school.’

‘It’s Saturday!’ says the woman, even as Nicola is backing down the path. ‘Come in for a cup of tea. I never see anybody.’

‘It’s Thursday!’ shouts Nicola back, picking up the bike. ‘I have to go to school.’

She bumps the racer off the kerb and hurries across the road, to the graveyard wall and the iron gate, rusted open, that sits where the wall turns a sharp ninety degrees, separating the cemetery from the thorny bushes bordering the old colliery. Why does the old woman do that, wait for her every morning? It always throws her, makes her think of what her mum says when she is having her bad days. You’ll be off soon, going to university, meeting a boy, settling down at the other side of the country. I’ll be all on my own. For God’s sake, mum, she’ll say. I’m only fourteen.

It is only when Nicola squeezes her bike through the old iron gate that she hears the woman’s door click shut. She throws her leg with difficulty over the frame, squeezing the brakes tight as she pauses at the top of the slope that leads down to the cemetery and joins the criss-crossing paths that meander between the graves. She doesn’t particularly like riding home through the cemetery but it is a full ten minutes quicker than going right back up to the main road and riding through the warren of streets to where she lives, and she’s already lost time talking to that daft old bat. At the centre of the sprawling cemetery the chapel sits, the harsh light burning through the tall windows. Old man Calderbank will give her hell for riding her bike through the graveyard if he catches her, and it isn’t officially open to the public at this time of day anyway, but Nicola will take the chance. Besides, she finds the light in the chapel comforting, in a way. She knows when she sees it the world hasn’t ended while she’s been out delivering her papers.

The snow is clean and unsullied in the cemetery, like Antarctica or the surface of the moon, maybe. Nicola’s racer tyres cleave slim gullies in the paths, and she freewheels along in a wide arc that takes her away from the chapel, and old Calderbank’s watchful eye, and towards the older part of the cemetery, where the headstones are larger and lean against one another. In the far corner the perimeter wall is half falling down, and she can pass her bike over and then it’s just a short ride across a patch of common ground to her estate.

Something catches Nicola’s eye as she coasts, a sudden movement flitting between the big old gravestones that startles her and causes her to involuntarily squeeze her brakes. Her wheels fail to find purchase in the fresh snow and she feels the bike skid, then list to the side, throwing her off into a drift of white powder.

Nicola rubs at her elbow and goes to retrieve her racer, rear wheel still spinning silently where it has fetched up against a gravestone. She looks around as she rights the bike; it must have been a fox, or even a deer.

As she brushes the snow from the saddle and the gears, something else catches Nicola’s eye. A series of indentations in the snow, among the graves. Footprints. She looks back at the thin track her bike has made in the path behind, and then at the jumble of imprints where she’s come off. They definitely aren’t her footprints. They are large, bigger than her size fives, and clear, the zig-zags of a boot or shoe sole. Their edges are sharp, they have been made recently. Old Calderbank, no doubt, come down from the chapel to give Nicola a ticking off. But the prints come from around the back of one of the old mausoleums, and weave between the headstones. Nicola looks back towards the chapel; the snow is pristine and undisturbed.

Nicola feels a chill, and shivers. It isn’t Calderbank, then, unless he’s flown over the graveyard from the chapel. She gets back on her bike and wishes now that she’d taken the long way round. She pushes her sleeve back and tries to angle her watch to catch the moonlight, then jumps, startled, as a black shape rushes by on the periphery of her vision. Suddenly panicked, Nicola pushes off but her foot slips, sending her bike skidding again. She drags the bike up and stamps the pedal forward, the low-slung handlebars coming up to meet her stomach and knocking the wind out of her as the pedals spin wildly. The chain has come off. She is about to abandon the bike there and then, run for the wall, when she hears a scuffling noise behind her.

She turns to see a shape rising up behind her, blocking out the silvery light of the moon. All she can think is Mum was right. It’s not safe for me out here. It’s not safe for me anywhere.

‘Don’t touch me!’ screams Nicola, closing her eyes tight and waiting for whatever is to come.

‘Oh, for God’s sake, I’m not going to bloody touch you,’ says Arthur crossly. He knows you have to be careful when dealing with kids these days. Back when he was a lad you’d routinely get a clip round the ear, or worse, from the local bobby, or the teachers, or a shopkeeper who didn’t like the look of you. You couldn’t get away with that today. And you had to be especially careful with girls. That lot down at the Black Diamond who sit in the snug, always banging on about asylum seekers and illegal immigrants, they keep a special watch out for kiddie-fiddlers as well. Think they’re some kind of avenging army or something. In the summer they’d painted ‘peedofile’, which even Arthur, with his limited education, knew wasn’t right, on the wall of one of the big houses up Springfield Lane. Turned out the place belonged to some poor bloke who was a paediatrician, which was a special doctor for children, at the Albert Edward Infirmary. They are idiots, but dangerous idiots. So, no, Arthur isn’t going to lay one finger on this chunky, pasty-faced girl sitting in the snow. But that doesn’t mean he’s not going to mark her card.

‘You shouldn’t be in the cemetery before it opens,’ says Arthur, pulling his big old donkey jacket tight around him. ‘And you shouldn’t be riding a bike in the cemetery at all. It’s the rules.’

The girl starts to tug at the loose chain with her stubby gloved fingers. Her doughy face is all crinkled up. Arthur realises she’s going to start crying.

‘See?’ he shouts. ‘See? This is what happens when children ride their bikes in the cemetery when it’s closed. Accidents happen. That’s why I live here, you know. To stop trespassers. To stop silly children hurting themselves.’

The girl’s bottom lip quivers. ‘I have to get home for my mum,’ she says, as though that’s Arthur’s problem. He shakes his head. ‘Give it here.’ He flips the chain back over the derailleur and lifts up the back wheel, spinning the pedal until it’s all fixed. ‘Now wheel it to the broken wall and lift it over. And don’t ride it in the cemetery again.’

The girl is staring at the old chapel. Arthur says, ‘It’s a bit big for you anyway, this bike.’

‘It was my dad’s,’ says the girl absently. ‘He died when I was a baby.’

Arthur frowns and peers at her. Ah. She’s that one. The one with the mother.

She says, ‘Does it have thick walls, your house?’

Arthur raises an eyebrow. ‘I suppose it does. Not thick enough to keep the cold out, though.’

The girl nods thoughtfully. ‘It would be a good place to be if there’s a war.’

‘A war with who?’ Funny thing for a girl that age to say. There was that trouble in Afghanistan he’d seen on the news, with that bunch, what were they called? The Taliban? And there’d been Bosnia, that finished last year. Used to be Yugoslavia. Led to all them asylum seekers coming over here, according to that mob in the Black Diamond. Or did she mean the IRA, who’d blown up all those folk in Manchester in the summer?

The girl shrugs and takes her bike. ‘I don’t know. My mum thinks there’ll be a war. She read something in the papers about the millennium. All the computers are going to switch themselves off at midnight. We’ll be fighting over food and water.’

Arthur has seen the girl’s mother. Heard talk about her. Not right in the head. Not surprising, if what he’s heard about the father is true. He feels a bit sorry for the girl now. ‘Don’t ride your bike in the cemetery again,’ he says again. ‘And don’t come in when it’s closed.’

The girl starts to wheel her racer off through the snow. He wonders if he should say something else, but decides he’d better leave it. He was never much good at talking to kids. Molly would have known what to say to her. It broke his heart, sometimes, when he saw her fussing over some baby in a pram or some kiddie done up in his finest at a churchwalking day or something. She’d have loved kids.

The girl has gone, swallowed by the shadows, and before Arthur knows it he’s standing at Molly’s grave. Seventy she’d have been on her birthday, just over two weeks away. They might have had a party or something, if she’d still been here. Maybe gone on holiday, somewhere warm. Though Molly would never have countenanced going away at Christmas. Seven years gone, she’s been. And he’s felt every day of it, like a burden he has to carry that feels just a little heavier every single morning when he gets up. There’s been times, he admits it, that he’s gone to bed and wished he wouldn’t wake up again. But it’s nearly her birthday, and he has to know. He has to know before it’s too late. He can’t die before he gets the answer.

Stirring his porridge, Arthur bangs on his chest with his fist. God knows what Carol Leigh put in that pie that Timmy brought round yesterday, but it’s not half given him a bout of heartburn. Not that he’s complaining; Arthur doesn’t want folk feeling sorry for him, but he’s not above taking a bit of charity. He takes a mouthful of his tea and puts the mug down on the Glen Campbell CD. He splutters; the tea’s gone down the wrong way. Covering his mouth as he starts to cough, he turns away from the pot of porridge and casts around for a handkerchief, his hands finding the Pwllheli tea towel the pie came wrapped in, and he hacks violently into it. Grimacing, Arthur balls up the tea towel and tosses it into the flames of the wood burner. Good job she didn’t want it back after all.

He’s quite gone off the idea of porridge now, and goes for a sit down. His arms and shoulders are aching; probably it’s just the cold getting to him, or maybe Molly was right and he shouldn’t have tackled that wall down at the end of Cemetery Road. Arthur quietly chides himself. Molly didn’t say any such thing. He’ll have to be careful he doesn’t let people catch him having his one-sided conversations with his dead wife. He doesn’t want anybody to think he’s doolally. Any excuse to cart him off to a home or something. Hopefully Timmy Leigh won’t be telling people Arthur was chatting away to his wife’s grave, bold as brass. But Arthur doesn’t think he will; he’s. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...