Now

Marcia tapped her temple. The state-provided eye she’d been fitted with when she’d been appointed county agent didn’t penetrate the low gray clouds. She knew the federal lifter was up there somewhere—at least it was scheduled to be up there—but damned if she could make it out.

She’d been at the grange for an hour already, coaxing the little harvesters and their counterparts who worked the silos through the backbreaking labor of loading and unloading the gravity wagons with their steeply pitched beds. The gleanings of the hillsides were bound for coastal cities nobody in the county would ever see and few could even name. Some of the carefully tailored grain might even end up overseas, for all anyone in the county knew.

An indicator light floated in Marcia’s vision, invisible to any onlookers. It began flashing amber.

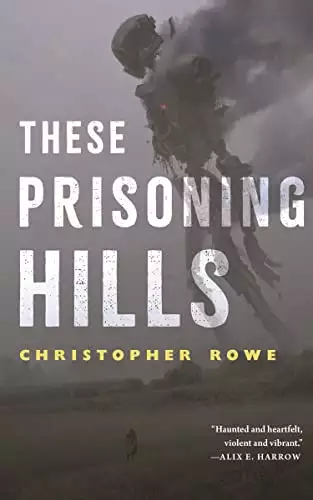

After a moment, the lifter began descending through the clouds, still concealed, but detectable by the swirls and eddies in the gray vapor.

The timing was good. The Federals were late, but they’d arrived before Marcia started thinking too much about the past. Thinking about the past—and about things that were concealed—crippled her some black nights.

The little harvesters scrambled clear of the grange’s landing pad. Marcia rechecked the manifests, wondering if the lifter was empty—which would mean clearing out the silos and an attendant bonus credited to the county—or if it was late in its schedule of pickups—which might mean it couldn’t take much of the harvest at all, leaving grain to rot.

There was a tug at her pants leg. One of the scar-faced silo hands, their skin tone an intense violet not found in nature like all the dependents of that specialty, looked up at her, blinking furiously and pointing out at the landing pad.

The lifter wasn’t a lifter. An ugly black craft, bristling with sensor suites and weapons arrays, settled to the ground on jets of steam.

The little harvesters milled around in confusion.

Then one of them started hustling forward, pushing their gravity wagon. A couple of the smarter ones stopped them before they reached the pad.

The light in Marcia’s field of vision had gone red. Her hands had gone cold.

* * *

“Agent, I don’t need anything from you but a couple of updated maps and the name of a local willing to guide us back into the hills.”

Marcia was sitting in the visitor’s chair of her own small office. The captain, a jaundiced-looking Hispanic man wearing the same mottled brown and gray fatigues as the squad of federal soldiers he commanded, had taken the chair behind her desk without a word.

The federal military arriving unannounced wasn’t something Marcia would ever have expected. But now that they were here, their commanding officer taking her chair without ceremony wasn’t surprising. Marcia would have done the same once.

“As I already told your sergeant, the maps you have are the newest I’ve seen, certainly newer than anything we have here. Nobody goes to that part of the county—it’s been quarantined since the peace. And we don’t have the benefit of eyes in the sky.”

The captain was probably thirty years younger than Marcia, too young to have fought in the war. But he had an edge to him. She didn’t doubt his competence, just the wisdom of his requests. He nodded at her.

“We’ll make do, then. What about a guide?”

He was ignoring what she’d said about eyes in the sky, which was probably a good thing for her. The high-flying drones and low-orbiting satellites the Federals used to monitor the Commonwealth and other treaty states were supposed to be secret because they were a violation of sovereignty. Marcia wasn’t interested in an argument about sovereignty with a man in command of a gunship.

The captain was also ignoring what she’d said about nobody going to the uplands anymore.

“I don’t have a name for you, Captain. The last census puts the county population at having dropped down to less than four hundred citizens, and maybe three times that harvesters, teamsters, and other dependents. I know them all. None of them know those hills.”

The captain pulled a length of wire from a pocket. It glowed blue. He fed it into his temple.

“You know those hills, Agent,” he said after a moment, his eyes distant and his voice hollow. “You were born in them.”

She’d expected this as soon as the sergeant had let slip the broad outlines of their orders. She’d thought she was prepared for it.

“Captain, I am sixty-one years old. I left the uplands when I was sixteen. Since then, the whole range from the Girding Wall north to . . . north to where I don’t know, New England, maybe, have gone through the Reseeding. And here in the Commonwealth all the mountains were subjected to eight years of sustained bombardment by both your employers and by the Voluntary State. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved