- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

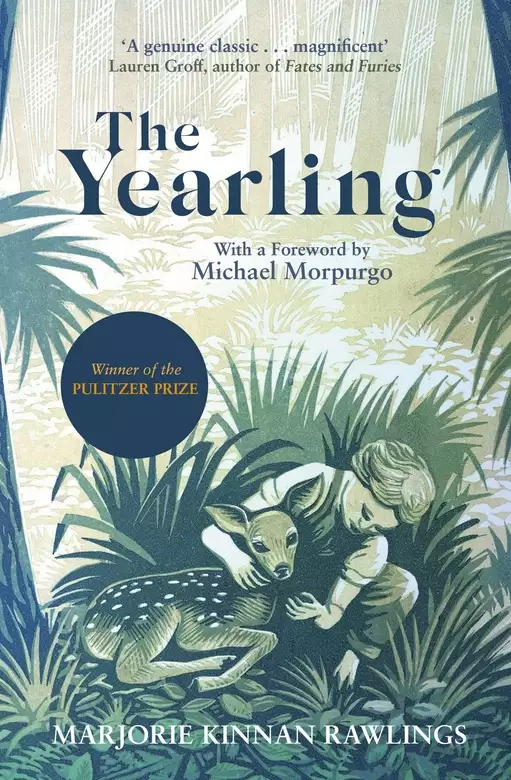

WINNER OF THE PULITZER PRIZE

'A literary masterpiece for all ages . . . a tale of growing up, of love and laughter, of tragedy and loss and grief - a tale that is so compelling that it turns the page for you: The Yearling leaves you tearful, breathless, exhilarated' MICHAEL MORPURGO

'A genuine classic . . . I was stunned to awe by The Yearling's beauty and strength' LAUREN GROFF

In the remote, unforgiving landscape of central Florida, Ezra 'Penny' Baxter, his wife Ora and their son Jody carve out a precarious existence. Only ever a failed crop away from disaster, life in the Big Scrub is one of lurking danger, wild beauty and the thrill of the hunt.

Jody's world is transformed when he rescues a starving fawn, who becomes his constant companion. But their bond is threatened when the yearling endangers the family's survival - and Jody is forced to make a terrible choice that will change him forever.

Winner of the 1939 Pulitzer Prize and an instant bestseller, The Yearling is a moving and richly evocative classic for readers of all ages.

Release date: September 1, 2001

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 208

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Yearling

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

The clearing itself was pleasant if the unweeded rows of young shafts of corn were not before him. The wild bees had found the chinaberry tree by the front gate. They burrowed into the fragile clusters of lavender bloom as greedily as though there were no other flowers in the scrub; as though they had forgotten the yellow jessamine of March; the sweet bay and the magnolias ahead of them in May. It occurred to him that he might follow the swift line of flight of the black and gold bodies, and so find a bee-tree, full of amber honey. The winter’s cane syrup was gone and most of the jellies. Finding a bee-tree was nobler work than hoeing, and the corn could wait another day. The afternoon was alive with a soft stirring. It bored into him as the bees bored into the chinaberry blossoms, so that he must be gone across the clearing, through the pines and down the road to the running branch. The bee-tree might be near the water.

He stood his hoe against the split-rail fence. He walked down the cornfield until he was out of sight of the cabin. He swung himself over the fence on his two hands. Old Julia the hound had followed his father in the wagon to Grahamsville, but Rip the bulldog and Perk the new feist saw the form clear the fence and ran toward him. Rip barked deeply but the voice of the small mongrel was high and shrill. They wagged deprecatory short tails when they recognized him. He sent them back to the yard. They watched after him indifferently. They were a sorry pair, he thought, good for nothing but the chase, the catch and the kill. They had no interest in him except when he brought them their plates of table scraps night and morning. Old Julia was a gentle thing with humans, but her worn-toothed devotion was only for his father, Penny Baxter. Jody had tried to make up to Julia, but she would have none of him.

‘You was pups together,’ his father told him, ‘ten year gone, when you was two year old and her a baby. You hurted the leetle thing, not meanin’ no harm. She cain’t bring herself to trust you. Hounds is often that-a-way.’

He made a circle around the sheds and corn-crib and cut south through the black-jack. He wished he had a dog like Grandma Hutto’s. It was white and curly-haired and did tricks. When Grandma Hutto laughed and shook and could not stop, the dog jumped into her lap and licked her face, wagging its plumed tail as though it laughed with her. He would like anything that was his own; that licked his face and followed him as old Julia followed his father. He cut into the sand road and began to run east. It was two miles to the Glen, but it seemed to Jody that he could run forever. There was no ache in his legs, as when he hoed the corn. He slowed down to make the road last longer. He had passed the big pines and left them behind. Where he walked now, the scrub had closed in, walling in the road with dense sand pines, each one so thin it seemed to the boy it might make kindling by itself. The road went up an incline. At the top he stopped. The April sky was framed by the tawny sand and the pines. It was as blue as his homespun shirt, dyed with Grandma Hutto’s indigo. Small clouds were stationary, like bolls of cotton. As he watched, the sunlight left the sky a moment and the clouds were gray.

‘There’ll come a little old drizzly rain before night-fall,’ he thought.

The down grade tempted him to a lope. He reached the thick-bedded sand of the Silver Glen road. The tar-flower was in bloom, and fetter-bush and sparkleberry. He slowed to a walk, so that he might pass the changing vegetation tree by tree, bush by bush, each one unique and familiar. He reached the magnolia tree where he had carved the wild-cat’s face. The growth was a sign that there was water nearby. It seemed a strange thing to him, when earth was earth and rain was rain, that scrawny pines should grow in the scrub, while by every branch and lake and river there grew magnolias. Dogs were the same everywhere, and oxen and mules and horses. But trees were different in different places.

‘Reckon it’s because they can’t move none,’ he decided. They took what food was in the soil under them.

The east bank of the road shelved suddenly. It dropped below him twenty feet to a spring. The bank was dense with magnolia and loblolly bay, sweet gum and gray-barked ash. He went down to the spring in the cool darkness of their shadows. A sharp pleasure came over him. This was a secret and a lovely place.

A spring as clear as well water bubbled up from nowhere in the sand. It was as though the banks cupped green leafy hands to hold it. There was a whirlpool where the water rose from the earth. Grains of sand boiled in it. Beyond the bank, the parent spring bubbled up at a higher level, cut itself a channel through white limestone and began to run rapidly down-hill to make a creek. The creek joined Lake George, Lake George was a part of the St John’s River, the great river flowed northward and into the sea. It excited Jody to watch the beginning of the ocean. There were other beginnings, true, but this one was his own. He liked to think that no one came here but himself and the wild animals and the thirsty birds.

He was warm from his jaunt. The dusky glen laid cool hands on him. He rolled up the hems of his blue denim breeches and stepped with bare dirty feet into the shallow spring. His toes sunk into the sand. It oozed softly between them and over his bony ankles. The water was so cold that for a moment it burned his skin. Then it made a rippling sound, flowing past his pipe-stem legs, and was entirely delicious. He walked up and down, digging his big toe experimentally under smooth rocks he encountered. A school of minnows flashed ahead of him down the growing branch. He chased them through the shallows. They were suddenly out of sight as though they had never existed. He crouched under a bared and overhanging live-oak root where a pool was deep, thinking they might reappear, but only a spring frog wriggled from under the mud, stared at him, and dove under the tree root in a spasmodic terror. He laughed.

‘I ain’t no ’coon. I’d not ketch you,’ he called after it.

A breeze parted the canopied limbs over him. The sun dropped through and lay on his head and shoulders. It was good to be warm at his head while his hard calloused feet were cold. The breeze died away, the sun no longer reached him. He waded across to the opposite bank where the growth was more open. A low palmetto brushed him. It reminded him that his knife was snug in his pocket; that he had planned as long ago as Christmas, to make himself a flutter-mill.

He had never built one alone. Grandma Hutto’s son Oliver had always made one for him whenever he was home from sea. He went to work intently, frowning as he tried to recall the exact angle necessary to make the mill-wheel turn smoothly. He cut two forked twigs and trimmed them into two Ys of the same size. Oliver had been very particular to have the crossbar round and smooth, he remembered. A wild cherry grew halfway up the bank. He climbed it and cut a twig as even as a polished pencil. He selected a palm frond and cut two strips of the tough fiber, an inch wide and four inches long. He cut a slit lengthwise in the center of each of them, wide enough to insert the cherry twig. The strips of palm frond must be at angles, like the arms of a windmill. He adjusted them carefully. He separated the Y-shaped twigs by nearly the length of the cherry cross-bar and pushed them deep into the sand of the branch bed a few yards below the spring.

The water was only a few inches deep but it ran strongly, with a firm current. The palm-frond mill-wheel must just brush the water’s surface. He experimented with depth until he was satisfied, then laid the cherry bar between the twigs. It hung motionless. He twisted it a moment, anxiously helping it to fit itself into its forked grooves. The bar began to rotate. The current caught the flexible tip of one bit of palm frond. By the time it lifted clear, the rotation of the bar brought the angled tip of the second into contact with the stream. The small leafy paddles swung over and over, up and down. The little wheel was turning. The flutter-mill was at work. It turned with the easy rhythm of the great water-mill at Lynne that ground corn into meal.

Jody drew a deep breath. He threw himself on the weedy sand close to the water and abandoned himself to the magic of motion. Up, over, down, up, over, down – the flutter-mill was enchanting. The bubbling spring would rise forever from the earth, the thin current was endless. The spring was the beginning of waters sliding to the sea. Unless leaves fell, or squirrels cut sweet bay twigs to drop and block the fragile wheel, the flutter-mill might turn forever. When he was an old man, as old as his father, there seemed no reason why this rippling movement might not continue as he had begun it.

He moved a stone that was matching its corners against his sharp ribs and burrowed a little, hollowing himself a nest for his hips and shoulders. He stretched out one arm and laid his head on it. A shaft of sunlight, warm and thin like a light patchwork quilt, lay across his body. He watched the flutter-mill indolently, sunk in the sand and the sunlight. The movement was hypnotic. His eyelids fluttered with the palm-leaf paddles. Drops of silver slipping from the wheel blurred together like the tail of a shooting star. The water made a sound like kittens lapping. A rain frog sang a moment and then was still. There was an instant when the boy hung at the edge of a high bank made of the soft fluff of broom-sage, and the rain frog and the starry dripping of the flutter-mill hung with him. Instead of falling over the edge, he sank into the softness. The blue, white-tufted sky closed over him. He slept.

When he awakened, he thought he was in a place other than the branch bed. He was in another world, so that for an instant he thought he might still be dreaming. The sun was gone, and all the light and shadow. There were no black holes of live oaks, no glossy green of magnolia leaves, no pattern of gold lace where the sun had sifted through the branches of the wild cherry. The world was all a gentle gray, and he lay in a mist as fine as spray from a waterfall. The mist tickled his skin. It was scarcely wet. It was at once warm and cool. He rolled over on his back and it was as though he looked up into the soft gray breast of a mourning dove.

He lay, absorbing the fine-dropped rain like a young plant. When his face was damp at last and his shirt was moist to the touch, he left his nest. He stopped short. A deer had come to the spring while he was sleeping. The fresh tracks came down the east bank and stopped at the water’s edge. They were sharp and pointed, the tracks of a doe. They sank deeply into the sand, so that he knew the doe was an old one and large. Perhaps she was heavy with fawn. She had come down and drunk deeply from the spring, not seeing him where he slept. Then she had scented him. There was a scuffled confusion in the sand where she had wheeled in fright. The tracks up the opposite bank had long harried streaks behind them. Perhaps she had not drunk, after all, before she scented him, and turned and ran with that swift, sand-throwing flight. He hoped she was not now thirsty, wide-eyed in the scrub.

He looked about for other tracks. The squirrels had raced up and down the banks, but they were bold, always. A raccoon had been that way, with his feet like sharp-nailed hands, but he could not be sure how recently. Only his father could tell for certain the hour when any wild things had passed by. Only the doe had surely come and had been frightened. He turned back again to the flutter-mill. It was turning as steadily as though it had always been there. The palm-leaf paddles were frail but they made a brave show of strength, rippling against the shallow water. They were glistening from the slow rain.

Jody looked at the sky. He could not tell the time of day in the grayness, nor how long he may have slept. He bounded up the west bank, where open gallberry flats spread without obstructions. As he stood, hesitant whether to go or stay, the rain ended as gently as it had begun. A light breeze stirred from the southwest. The sun came out. The clouds rolled together into great white billowing feather bolsters, and across the east a rainbow arched, so lovely and so various that Jody thought he would burst with looking at it. The earth was pale green, the air itself was all but visible, golden with the rain-washed sunlight, and all the trees and grass and bushes glittered, varnished with the rain-drops.

A spring of delight boiled up within him as irresistibly as the spring of the branch. He lifted his arms and held them straight from his shoulders like a water-turkey’s wings. He began to whirl around in his tracks. He whirled faster and faster until his ecstasy was a whirlpool, and when he thought he would explode with it, he became dizzy and closed his eyes and dropped to the ground and lay flat in the broom-sage. The earth whirled under him and with him. He opened his eyes and the blue April sky and the cotton clouds whirled over him. Boy and earth and trees and sky spun together. The whirling stopped, his head cleared and he got to his feet. He was light-headed and giddy, but something in him was relieved, and the April day could be borne again, like any ordinary day.

He turned and galloped toward home. He drew deep breaths of the pines, aromatic with wetness. The loose sand that had pulled at his feet was firmed by the rain. The return was comfortable going. The sun was not far from its setting when the long-leaf pines around the Baxter clearing came into sight. They stood tall and dark against the red-gold west. He heard the chickens clucking and quarreling and knew they had just been fed. He turned into the clearing. The weathered gray of the split-rail fence was luminous in the rich spring light. Smoke curled thickly from the stick-and-clay chimney. Supper would be ready on the hearth and hot bread baking in the Dutch oven. He hoped his father had not returned from Grahamsville. It came to him for the first time that perhaps he should not have left the place while his father was away. If his mother had needed wood, she would be angry. Even his father would shake his head a little and say, ‘Son—’ He heard old Caesar snort and knew his father was ahead of him.

The clearing was in a pleasant clatter. The horse whinnied at the gate, the calf bleated in its stall and the milch cow answered, the chickens scratched and cackled and the dogs barked with the coming of food and evening. It was good to be hungry and to be fed and the stock was eager with an expectant certainty. The end of winter had been meager; corn short, and hay, and dried cow-peas. But now in April the pastures were green and succulent and even the chickens savored the sprouts of young grass. The dogs had found a nest of young rabbits that evening, and after such tid-bits the scraps from the Baxter supper table were a matter of some indifference. Jody saw old Julia lying under the wagon, worn out from her miles of trotting. He swung open the front paling gate and went to find his father.

Penny Baxter was at the wood-pile. He still wore the coat of the broadcloth suit that he had been married in, that he now wore as badge of his gentility when he went to church, or off trading. The sleeves were too short, not because Penny had grown, but because the years of hanging through the summer dampness, and being pressed with the smoothing iron and pressed again, had somehow shrunk the fabric. Jody saw his father’s hands, big for the rest of him, close around a bundle of wood. He was doing Jody’s work, and in his good coat. Jody ran to him.

‘I’ll git it, Pa.’

He hoped his willingness, now, would cover his delinquency. His father straightened his back.

‘I near about give you out, son,’ he said.

‘I went to the Glen.’

‘Hit were a mighty purty day to go,’ Penny said. ‘Or to go anywhere. How come you to take out such a fur piece?’

It was as hard to remember why he had gone as though it had been a year ago. He had to think back to the moment when he had laid down his hoe.

‘Oh.’ He had it now. ‘I aimed to foller the honey-bees and find a bee-tree.’

‘You find it?’

Jody stared blankly.

‘Dogged if I ain’t forgot ’til now to look for it.’

He felt as foolish as a bird-dog caught chasing field mice. He looked at his father sheepishly. His father’s pale blue eyes were twinkling.

‘Tell the truth, Jody,’ he said, ‘and shame the devil. Wa’n’t the bee-tree a fine excuse to go a-ramblin’?’

Jody grinned.

‘The notion takened me,’ he admitted, ‘afore I studied on the bee-tree.’

‘That’s what I figgered. How come me to know, was when I was drivin’ along to Grahamsville, I said to myself, “There’s Jody now, and the hoein’ ain’t goin’ to take him too long. What would I do this fine spring day, was I a boy?” And then I thought, “I’d go a-ramblin’.” Most anywhere, long as it kivered the ground.’

A warmth filled the boy that was not the low golden sun. He nodded.

‘That’s the way I figgered,’ he said.

‘But your Ma, now,’ Penny jerked his head toward the house, ‘don’t hold with ramblin’. Most women-folks cain’t see for their lives, how a man loves so to ramble. I never let on you wasn’t here. She said, “Where’s Jody?” and I said, “Oh, I reckon he’s around some’eres.”’

He winked one eye and Jody winked back.

‘Men-folks has got to stick together in the name o’ peace. You carry your Ma a good bait o’ wood now.’

Jody filled his arms and hurried to the house. His mother was kneeling at the hearth. The spiced smells that came to his nose made him weak with hunger.

‘That ain’t sweet ’tater pone, is it, Ma?’

‘Hit’s sweet ’tater pone, and don’t you fellers be too long a time now, piddlin’ around and visitin’. Supper’s done and ready.’

He dumped the wood in the box and scurried to the lot. His father was milking Trixie.

‘Ma says to git done and come on,’ he reported. ‘Must I feed old Caesar?’

‘I done fed him, son, sich as I had to give the pore feller.’ He stood up from the three-legged milking stool. ‘Carry in the milk and don’t trip and waste it outen the gourd like you done yestiddy. Easy, Trixie—’

He moved aside from the cow and went to the stall in the shed, where her calf was tethered.

‘Here, Trixie. Soo, gal—’

The cow lowed and came to her calf.

‘Easy, there. You greedy as Jody.’

He stroked the pair and followed the boy to the house. They washed in turn at the water-shelf and dried their hands and faces on the roller towel hanging outside the kitchen door. Ma Baxter sat at the table waiting for them, helping their plates. Her bulky frame filled the end of the long narrow table. Jody and his father sat down on either side of her. It seemed natural to both of them that she should preside.

‘You-all hongry tonight?’ she asked.

‘I kin hold a barrel o’ meat and a bushel o’ biscuit,’ Jody said.

‘That’s what you say. Your eyes is bigger’n your belly.’

‘I’d about say the same,’ Penny said, ‘if I hadn’t learned better. Goin’ to Grahamsville allus do make me hongry.’

‘You git a snort o’ ’shine there, is the reason,’ she said.

‘A mighty small one today. Jim Turnbuckle treated.’

‘Then you shore didn’t git enough to hurt you.’

Jody heard nothing; saw nothing but his plate. He had never been so hungry in his life, and after a lean winter and slow spring, with food not much more plentiful for the Baxters than for their stock, his mother had cooked a supper good enough for the preacher. There were poke-greens with bits of white bacon buried in them; sand-buggers made of potato and onion and the cooter he had found crawling yesterday; sour orange biscuits and at his mother’s elbow the sweet potato pone. He was torn between his desire for more biscuits and another sand-bugger and the knowledge, born of painful experience, that if he ate them, he would suddenly have no room for pone. The choice was plain.

‘Ma,’ he said, ‘kin I have my pone right now?’

She was at a pause in the feeding of her own large frame. She cut him, dexterously, a generous portion. He plunged into its spiced and savory goodness.

‘The time it takened me,’ she complained, ‘to make that pone – and you destroyin’ it before I git my breath—’

‘I’m eatin’ it quick,’ he admitted, ‘but I’ll remember it a long time.’

Supper was done with. Jody was replete. Even his father, who usually ate like a sparrow, had taken a second helping.

‘I’m full, thank the Lord,’ he said.

Ma Baxter sighed.

‘If a feller’d light me a candle,’ she said, ‘I’d git shut o’ the dishwashin’ and mebbe have time to set and enjoy myself.’

Jody left his seat and lit a tallow candle. As the yellow flame wavered, he looked out of the east window. The full moon was rising.

‘A pity to waste light, ain’t it,’ his father said, ‘and the full moon shinin’!’

He came to the window and they watched it together,

‘Son, what do it put in your head? Do you mind what we said we’d do, full moon in April?’

‘I dis-remember.’

Somehow, the seasons always took him unawares. It must be necessary to be as old as his father to keep them in the mind and memory, to remember moon-time from one year’s end to another.

‘You ain’t forgot what I told you? I’ll swear, Jody. Why, boy, the bears comes outen their winter beds on the full moon in April.’

‘Old Slewfoot! You said we’d lay for him when he come out!’

‘That’s it.’

‘You said we’d go where we seed his tracks comin’ and goin’ and criss-crossin’, and likely find his bed, and him, too, comin’ out in April.’

‘And fat. Fat and lazy. The meat so sweet, from him layin’ up.’

‘And him mebbe easier to ketch, not woke up good.’

‘That’s it.’

‘When kin we go, Pa?’

‘Soon as we git the hoein’ done. And see bear-sign.’

‘Which-a-way will we begin huntin’ him?’

‘We’d best to go by the Glen springs and see has he come out and watered there.’

‘A big ol’ doe watered there today,’ Jody said. ‘Whilst I was asleep. I built me a flutter-mill, Pa. It run fine.’

Ma Baxter stopped the clatter of her pots and pans.

‘You sly scaper,’ she said. ‘That’s the first I knowed you been off. You gittin’ slick as a clay road in the rain.’

He shouted with laughter.

‘I fooled you, Ma. Say it, Ma, I got to fool you oncet.’

‘You fooled me. And me standin’ over the fire makin’ potato pone—’

She was not truly angry.

‘Now, Ma,’ he cajoled her, ‘suppose I was a varmint and didn’t eat nothin’ but roots and grass.’

‘I’d not have nothin’ then to rile me,’ she said.

At the same time he saw her mouth twist. She tried to straighten it and could not.

‘Ma’s a-laughin’! Ma’s a-laughin’! You ain’t riled when you laugh!’

He darted behind her and untied her apron strings. The apron slipped to the floor. She turned her bulk quickly and boxed his ears, but the blows were feather-light and playful. The same delirium came over him again that he had felt in the afternoon. He began to whirl around and around as he had done in the broom-sage.

‘You knock them plates offen the table,’ she said, ‘and you’ll see who’s riled.’

‘I cain’t he’p it. I’m dizzy.’

‘You’re addled,’ she said. ‘Jest plain addled.’

It was true. He was addled with April. He was dizzy with Spring. He was as drunk as Lem Forrester on a Saturday night. His head was swimming with the strong brew made up of the sun and the air and the thin gray rain. The flutter-mill had made him drunk, and the doe’s coming, and his father’s hiding his absence, and his mother’s making him a pone and laughing at him. He was stabbed with the candle-light inside the safe comfort of the cabin; with the moonlight around it. He pictured old Slewfoot, the great black outlaw bear with one toe missing, rearing up in his winter bed and tasting the soft air and smelling the moonlight, as he, Jody, smelled and tasted them. He went to bed in a fever and could not sleep. A mark was on him from the day’s delight, so that all his life, when April was a thin green and the flavor of rain was on his tongue, an old wound would throb and a nostalgia would fill him for something he could not quite remember. A whip-poor-will called across the bright night, and suddenly he was asleep.

Penny Baxter lay awake beside the vast sleeping bulk of his wife. He was always wakeful on the full moon. He had often wondered whether, with the light so bright, men were not meant to go into their fields and labor. He would like to slip from his bed and perhaps cut down an oak for wood, or finish the hoeing that Jody had left undone.

‘I reckon I’d ought to of crawled him about it,’ he thought.

In his day, he would have been thoroughly thrashed for slipping away and idling. His father would have sent him back to the spring, without his supper, to tear out the flutter-mill.

‘But that’s it,’ he thought. ‘A boy ain’t a boy too long.’

As he looked back over the years, he himself had had no boyhood. His own father had been a preacher, stern as the Old Testament God. The living had come, however, not from the Word, but from the small farm near Volusia on which he had raised a large family. He had taught them to read and write and to know the Scriptures, but all of them, from the time they could toddle behind him down the corn rows, carrying the sack of seed, had toiled until their small bones ached and their growing fingers cramped. Rations had been short and hookworm abundant. Penny had grown to maturity no bigger than a boy. His feet were small, his shoulders narrow, his ribs and hips jointed together in a continuous fragile framework. He had stood among the Forresters one day, like an ash sapling among giant oaks.

Lem Forrester looked down at him and said, ‘Why, you leetle ol’ penny-piece, you. You’re good money, a’right, but hit jest don’t come no smaller. Leetle ol’ Penny Baxter—’

The name had been his only one ever since. When he voted, he signed himself ‘Ezra Ezekial Baxter,’ but when he paid his taxes, he was put down as ‘Penny Baxter’ and made no protest. But he was a sound amalgam; sound as copper itself; and with something, too, of the copper’s softness. He leaned backward in his honesty, so that he was often a temptation to storekeepers and mill-owners and horse-traders. Storekeeper Boyles at Volusia, as honest as he, had once given him a dollar too much in change. His horse being lame, Penny had walked the long miles back again to return it.

‘The next time you came to trade would have done,’ Boyles said.

‘I know,’ Penny answered him, ‘but ’twa’n’t mine and I wouldn’t of wanted to die with it on me. Dead or alive, I only want what’s mine.’

The remark might have explained, to those who puzzled at him, his migration to the adjacent scrub. Folk who lived along the deep and placid river, alive with craft, with dugouts and scows, lumber rafts and freight and passenger vessels, sidewheel steamers that almost filled the stream, in places, from bank to bank, had said that Penny Baxter was either a brave man or a crazy one to leave the common way of life and take his bride into the very heart of the wild Florida scrub, populous with bears and wolves and panthers. It had been understandable for the Forresters to go there, for the growing family of great burly quarrelsome males needed all the room in the county, and freedom from any hindrance. But who would hinder Penny Baxter?

It was not hindrance – But in the towns and villages, in farming sections where neighbors were not too far apart, men’s minds and actions and property overlapped. There were intrusions on the individual spirit. There were friendliness and mutual help in time of trouble, true, but there were bickerings and watchfulness, one man suspicious of another. He had grown from under the sternness of his father into a world less direct, less honest, in its harshness, and therefore more disturbing.

He had perhaps been bruised too often. The peace of the vast aloof scrub had drawn him with the beneficence of its silence. Something in him was raw and tender. The touch of men was hurtful upon it, but the touch of the pines was healing. Making a living came harder there, distances were troublesome in the buying of supplies and the marketing of crops. But the clearing was peculiarly his own. The wild animals seemed less predatory to him than people he had known. The forays of bear and wolf and wild-cat and panther on stock were understandable, which was more than he could say of human cruelties.

In his thirties he had married a buxom girl, already twice his size, lo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...