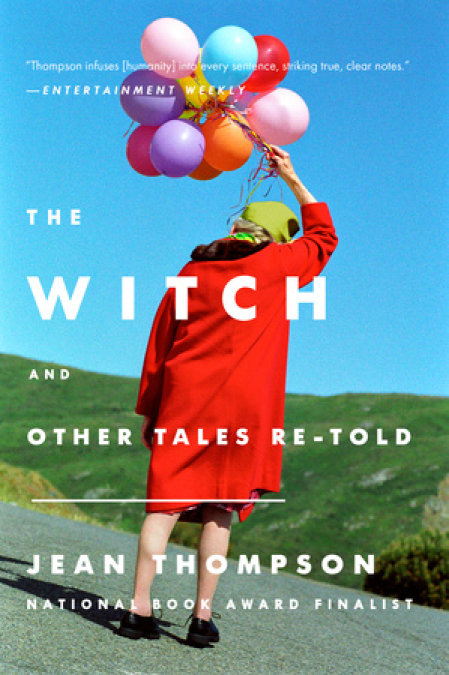

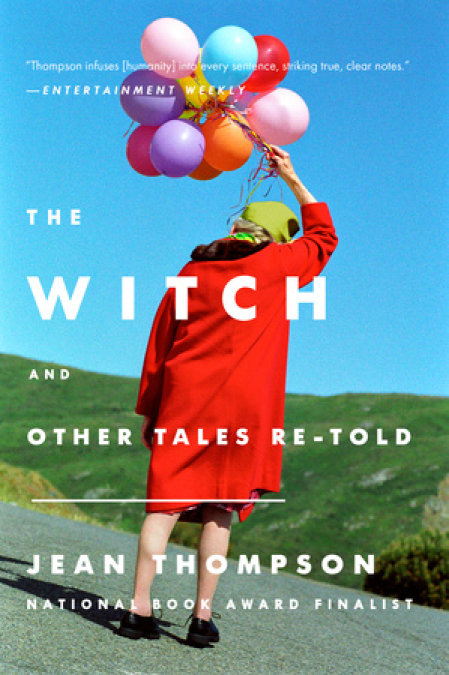

The Witch

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

National Book Award finalist and New York Times bestselling author Jean Thompson’s new collection of “bewitching improvisations on fairy tales” are “spellbinding” (Booklist, starred review).

Capturing the magic and horror in everyday life, The Witch and Other Tales Re-told revisits beloved fables that represent our deepest, most primeval fears and satisfy our longings for good to triumph over evil (preferably in the most gruesome way possible). From the wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood” to the beauty asleep in her castle, The Witch and Other Tales Re-told triumphantly brings the fairy tale into the modern age.

Release date: September 25, 2014

Publisher: Plume

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Witch

Jean Thompson

Copyright © 2014 by Jean Thompson

THE WITCH

My brother and I were given over to the Department of Children and Family Services after our father and his girlfriend left us alone in the car one too many times. The reason we were put in the car had to do with some trouble when we were younger, in some of the different places that we lived, when we were left home by ourselves. Neighbors had made calls and DCFS had come around, turning our father into a concerned and head-nodding parent, at least while the interview lasted. Once the investigator left, he had things to say about people who tried to tell you what to do with your own goddamn kids. They should just shut their faces. “Let’s go,” he said. “In the car, now. Vamoose.” He wasn’t bad-tempered, at least not as a rule, but people who thought they were better than us, by way of criticism or interference, brought out the angry side of him.

At the time when everything changed for us, my brother Kerry was seven and I was five. We knew the rules, the chief one being: Stay in the car! We accepted that there were complicated, unexplained adult things that we were not a part of, in places where we were not allowed. But sometimes we were scooped up, Kerry and me, and brought inside to a room with people and noise and the wonderful colored lights of cigarette machines and jukeboxes, encouraged to tell people our names, wear somebody’s baseball cap, and drink the Cokes prepared for us with straws and maraschino cherries.

And sometimes Monica, our father’s girlfriend, drove. Then she’d stay in the car with us and keep the engine running while our father went inside some unfamiliar restaurant or house. These errands made Monica nervous, made her speak sharply to us and turn around in her seat to keep watch, some worry in the air that filled Kerry and me with the uncomprehending anxiety of dogs. And when our father finally returned, we were all so glad to see him!

But mostly it was just me and Kerry, left on our own to wait. We were fine with being in the car, a maroon Chevy, not new, that drove like a boat. We knew its territories of front and back, its resources, its smells and textures. We always had something given to us to eat, like cheese popcorn, two bags, so that there would be no fighting. We had a portable radio, only one of those, so that we did fight over it, but the fighting was also a way of keeping busy.

Most often we fell asleep and woke up when our father and Monica returned, carrying on whatever conversation or argument was in progress, telling us to go back to sleep. The car started and we were borne away, watching streetlights through a bit of window, this one and this one and this one, all left behind by our motion, and this was a comfort.

Normal is whatever you grow up with. Sometimes Monica made us French toast with syrup for breakfast, and so we whined for French toast whenever we thought it might pay off. We had television to watch, and our intense, competitive friendships with kids we saw in the hallways and stairwells. All of this to say, we didn’t think anything was so bad. We knew bad right away when it showed up.

Kerry was a crybaby. Our father said so. Kerry was a candy ass. This was said in a spirit of encouragement and exhortation, since it was a worrisome thing for a boy to be soft, not stand up to teasing or hardship. People would keep coming at you. When Kerry tried not to cry, it was just as pitiful as the crying itself. He had a round chin and a full lower lip that quavered, or, as our father used to say, “You could ride that lower lip home!”

The expectations were different for girls, and anyway, I didn’t need the same advice about standing up for myself. Our father’s name for me was Little Big Mouth. I didn’t have a portion of Kerry’s fair good looks either; everything about me was browner and sharper. I don’t know why we were so different, why I couldn’t have been more sweet-tempered, why Kerry didn’t have more fight in him. Throughout my life I’ve struggled with the notion of things that were someone’s fault, of things that were done on purpose, and it was a relief when I finally came to understand that one thing we are not to blame for is our own natures.

Monica hadn’t always been with us. I knew that from having it told to me, and Kerry claimed he could remember the very day we met her. I said I did too, even though I didn’t. My baby memories were too confused, and how were you supposed to remember somebody not being there? Or maybe she had been around us but not yet living with us as she did now. I think she was a little slow, with a ceiling on her comprehension. She had a round, pop-eyed face and limp black hair that she wore long, and she favored purplish lipstick that coated the ends of her cigarettes. If Kerry or I did something we weren’t supposed to, she waved her hands and said, “You kids! Why you don’t behave? I’m telling your dad on you!” We never paid attention. Monica wasn’t entirely an adult, we sensed, and could be disregarded without consequences.

Our father didn’t like to sit home. He’d done something that involved driving—a truck? a bus?—until he hurt his back and couldn’t work regular hours. His back still pained him and we learned to walk wide of him when it put him in a mood. But if he was feeling good enough, or even borderline, he needed to get out and blow the stink off, as he called it, see and be seen, claim his old place among other men of the world. And since Monica wasn’t going to be left behind, and since now we could not be left behind either, we all went.

One problem with staying in the car was when we had to go to the bathroom. Sometimes either Monica or our father came to check on us and carry us to some back entrance or passageway where there was a toilet. At other times they didn’t come and didn’t come, and we tried not to wet ourselves, or sometimes we did and were shamed.

Once, whimpering from urgency, Kerry got out of the car and stood behind some trash containers to pee. I watched, unbelieving and horrified. And jealous at how much easier it was for boys to manage these things. “I’m telling,” I said, when Kerry let himself back in and relocked the car door.

“You better not.”

“I don’t have to, they can see right where you peed.”

He looked out the window to see if that was true. “No you can’t,” he said, but he didn’t sound so sure.

“You are going to get beat bloody.” It was one of our father’s occasional pronouncements, although so far we had not been made to bleed.

“Shut up.” He kicked me and I kicked back.

When our father and Monica returned, they were fizzy and cheerful. “How are my little buckaroos?” my father asked. “How’s the desperadoes?”

We said, faintly, that we were okay. Monica said, “They look hungry.”

“Now how can you tell that by looking? Let’s get a move on.”

“You know what sounds good right about now? Chicken and waffles. Where’s a place around here we can get that?”

“Some other time, Mon.”

“That’s not fair. I bet if you was the one wanted chicken and waffles, we’d be halfway there by now.”

“Shut it, Monica,” our father said, but not unpleasantly, because he was in such fine spirits. “If you were the one with the car, you could drive yourself to the moon.” He turned on the radio and started singing along with it.

Kerry and I kept quiet in the back seat, and I didn’t give him up. Like it or not, we were stuck together in some things.

So the next time I had to go, I told Kerry, “Move.” He was sitting next to the door on the sidewalk side. On the street, cars passed by us fast, with a shivery sound of rushing air.

“You better not.”

I popped out and made a face at him through the car window. I walked a little way, looking for a good place. But everything was out in the open, and it wasn’t fully dark yet, and I didn’t think I could crouch down and pee on the sidewalk, in front of everyone. I didn’t know where our father and Monica had gone. None of the buildings looked likely. I kept walking.

Behind me, a car door slammed, and Kerry ran to catch up with me. “You’re gonna be in trouble.”

“Well so are you now.”

Kerry walked backward in front of me. “Where are you going?”

“Home.”

“Uh-uh!”

I ignored him. He didn’t have any way to stop me.

“You don’t know where it is.”

“Yes I do.” I didn’t think we were that far away. And both Kerry and I wore house keys around our necks on shoelaces, just in case.

Kerry looked back at the car. It wasn’t too late for him to return to it, but he kept walking with me, looking all worried. “Candy ass,” I said.

“You’re a candy ass,” he said, but that was so lame, I didn’t bother answering back.

If I’d found anyplace I could have peed, or if we’d managed to get ourselves home, things would have gone differently. But we walked and walked, and the street didn’t offer anything like a bathroom, and we came to an intersection I didn’t recognize, though I set off with confidence in one direction. Walking, I didn’t have to go so bad. I thought I could keep on for a while.

Kerry lagged a pace or two behind me. He thought I was going to get in trouble and he was trying to stay out of the way. It was dark by now and the lights around us, from cars, streetlights, store windows, were bright and glassy, and the shadows beyond the lights were a reaching-out kind of black.

I’d been lost for a while. I knew it but I didn’t want to come out and say it, and anyway, I had the idea that I could find our building if I only looked hard enough. At least I think that’s how I thought. I was five, and it was a whole world ago.

The street was becoming less and less promising. There were vacant lots with chewed-looking weeds, and the gobbling noise of loud music from a passing car. I wondered if our father and Monica had come back yet and found us missing, or if they were still inside having their important fun. I was holding on to my pee so tight, I was having trouble walking. We came to a big lighted storefront, a grocery, with people going in and out of the automatic doors, and we hung back, afraid of getting in the way.

A lady on her way out of the store stopped and peered down at us. “Harold,” she said to the man with her, “look, two little white babies.”

Because we were white, and the lady and the man and everybody else around us was black.

“Where’s your mamma?” the lady said, and we just stared at her. We didn’t have one of those. “Awright, no matter, we fine her for you. You-all lost? Harold, you go put them bags up and come right back.” She squatted down in front of us. “Can you talk, honey?”

“I have to go to the bathroom,” I announced. Now that there was somebody to complain to, I was tearing up.

“Yeah?” She took my hand. “Come on with me, then. Brother too.” She held out her other hand to Kerry, who was sniffling now. We were both moved by our own piteousness.

She led us through the store, back to the place with gray mops resting in buckets, jugs of blue industrial cleanser, and a small, walled-off toilet. The lady asked if I needed any help, and it shocked me to think of some strange lady watching me pee, though she was just being nice. After I came out, Kerry said he had to go too, and then the lady directed us to wash our hands, lifting us up so we could reach the utility sink. She took us back through the store again, and we were set on a bench in an office where a radio played, and given cartons of chocolate milk and a package of cake doughnuts to eat.

And shouldn’t everything have been all right then? We had been found, tended to, soothed. Our father and Monica should have come in, full of remorse and relief, to bear us away, and promise never to let us out of their sight again. Or maybe we could have gone home with the lady who found us. She seemed to know a thing or two about children. She and Harold could have taken us in, two strange little white birds hatched in a different nest, and we would have begun a new, improbable life.

Instead the police were called, and protective services, and different adult strangers herded us this way and that, talking in ways that were meant to be reassuring, I guess, but the enormity of what was happening made us both cry. Of course they had all seen crying children before, and children who had been beaten, burned, starved, violated, in much worse shape than Kerry and I. They were, perhaps, a little brusque with us, a little impatient. We sat in a room decorated with crayon drawings, with books and puzzles and rag dolls and toy trucks, and these were meant to distract and amuse us, but none of them were our toys, and we hung back from them.

Because it was already so late, too late to do anything else with us, Kerry and I spent the night in a kind of dormitory with blue night lights on the walls, wearing clean, much-laundered pajamas, each of us tucked in with some other child’s stuffed bear. We were the only ones sleeping there, though we heard adult feet passing the open door and, from other rooms, different shrill or urgent sounds. I must have slept. But I kept waking up and seeing the blue lights and then I would remember everything that had happened, the weight of it sliding onto me in an instant.

I heard Kerry in the next bed, moving and restless. “Are you awake?” I whispered.

“Why did you get out of the car?” he said, and his voice was thick and full of snot from all his crying.

“Shut up.”

“You weren’t supposed to.”

“Well you did too.”

“You started it!”

Some noise beyond the doorway made us stop talking, and fall back into uneasy sleep. This was exactly the weight bearing down on me: the knowledge that I had set a terrible thing in motion.

In the morning we thought that we’d be going home now. But after breakfast (juice, apple slices, oatmeal that curdled in our mouths), it was explained to us that we would be going to stay at a lady’s house for a while. There were some things that had to be discussed with our father. He was fine, he said to tell us hello, and that he missed us. (Kerry and I looked down at the floor at this. It was not a thing our father would say.) Meanwhile, we would be with Mrs. Wojo (her name was longer and more complicated, but that is what we heard), a lady who helped out with children when they needed a place to stay.

I said that we didn’t need a place to stay, we just needed to go home. But we would not be going home. Explained and repeated to us by adults who had so much practice in telling children unpleasant things. We were going to Mrs. Wojo’s.

Was our father mad at us, was that why he wouldn’t come for us? Did he really know where we were, or were they making that up?

In the car on our way to Mrs. Wojo’s, I tried to memorize landmarks so that we could find our way back to somewhere familiar. One of the DCFS people, a woman, sat in the back seat between Kerry and me so I couldn’t talk to him. Another woman drove, and I guess they had names but I’ve forgotten them. It was one of those spring days that freezes up and turns water in gutters to oil-covered sumps, and a scouring wind pours out of the sky. We passed blocks and blocks of old warehouses, black-windowed buildings of dark red brick where nothing had happened for a very long time. A fenced-off park with a baseball diamond, chill and empty. Some streets of ordinary commerce, little shops and car lots and motels.

I wasn’t crying now. I was too sore-hearted and tired. I watched the cold world slide by outside, and it seemed like there was nowhere in it for me. The car turned and turned, and here were streets of small houses. They were shingled in white, green, or gray, each with some kind of porch or stoop, each with its own small square yard set off with board fences. The car slowed and pulled over to the curb. “Okay, kids,” the DCFS woman in the back seat with us said, in the voice adults use to try to head off any trouble, cheery and energetic but full of lurking strain. “Here we are!”

At least the house looked nice. It was white with red trim, and frilly curtains in the windows. It was too early in the season for flowers, but the window boxes were filled with red plastic geraniums. Someone was at least making an effort. Kerry and I were led up the front steps and the DCFS woman rang the bell. The front door was gated off with an ironwork barrier, painted white, and beyond that was a glass panel, and beyond that, a lace curtain.

The curtain stirred and there were a great many sounds of locks unsnapping and bolts sliding before we were admitted. The DCFS woman put a hand on each of our shoulders and propelled us forward. “This is Kerry. And this is Jo.”

Too many things were happening at once for me to take everything in, but later I learned the details of that room by heart: the reclining chair, exclusive to the use of Mrs. Wojo, with the protective plastic doily across the back. The television table alongside where the remote control lived, and the different items necessary for the comfort and convenience of Mrs. Wojo. Kleenex, ashtray, eyeglasses case, crossword puzzle book with the small gold pen hitched to its spine. The television itself, furniture-like and old-fashioned even for that time. The line of African violets on the windowsill, each of them set on top of a cottage cheese carton with a wick made of nylon stocking. The plaid sofa with the clear plastic hood laid over the back cushions, the lamp with the base in the shape of a ceramic fish balanced on its tail. The carpet, a dank green. The air had a thickened quality, different layers of smells. Cigarettes, something yeasty, something burnt, and many cleaning products.

Mrs. Wojo stooped to get down close to us. “Hello, children.” She had a powdery face, with powder under her lipstick too, so that her red mouth was worked into paste in the corners. She wore eyeglasses with pink frames and her hair was gray and puffed out. Like the house, she had layers of smells: soap, hair spray, undergarments, Pond’s hand cream. And in the moment her face was closest to mine, she breathed out, and I smelled not just cigarettes, but something black, dead, fouled in her, and I knew her for what she was, and she saw that I knew it and her eyes glittered even as her mouth still smiled.

“Can they have candy?” she asked the DCFS woman. “Would you like some candy?” She held out a glass bowl with a mound of lemon drops stuck together. Kerry and I each picked one loose. “What do you say?” Mrs. Wojo prompted us, and we each said thank you.

The candies were hard and they stayed in a lump under our tongues for a long time.

Then we were taken upstairs to see the bedroom prepared for us, two little beds made up with checkerboard quilts, one blue, one yellow, and a dresser and a closet for all the clothes we didn’t have. (These arrived later, collected from our home and transported in paper bags.)

The bathroom was downstairs, tiled in green, with a shower curtain patterned in seashells. Mrs. Wojo’s magisterial bedroom was next to it. We caught a glimpse of dark wood and a white chenille bedspread. Mrs. Wojo and the DCFS woman had a number of things to discuss, while Kerry and I stayed silent. Kerry kept rubbing his eyes like he was sleepy, but it turned out there was something wrong with them, pinkeye, and I caught it too and we both had to have ointment squeezed into our eyes, which we fought as hard as we could, our hair yanked back to make us submit and stay still.

But this was yet to come. The two adults finished their talking, and the DCFS woman prepared to leave. She said that she would be back to see us soon, and that we should behave and do everything that Mrs. Wojo told us to. Mrs. Wojo escorted her out, saying goodbye in a musical voice. Then she redid all the locks and bolts and turned to face us.

“Kerry,” she said. “That’s a girl’s name. Are you a little girl?” She lifted a piece of his long, fair hair. “We’ll get this cut so you don’t turn femmy.”

Then she looked at me. “Joe, that’s a boy’s name. Did somebody think that was funny? Both of you named queer?”

“I’m Joanne,” I said, not knowing what queer was, except that I didn’t want to be it.

“That’s not much better, is it? My name is Mrs. —” And here she spoke her full name, that impossible sequence of tangled consonants. “Say it.”

“Mrs. Wohohohoho,” Kerry and I came up with. She shook her head.

“Not the sharpest knives in the drawer, are you? Never mind. Go play in the back yard while I get your lunch ready.”

We still had our coats on. She took us through the kitchen, with its enormous gas stove and more of the African violets set on a window ledge, and a smell of dishrags, out to a landing. Stairs led down to a basement, and opposite, the back door. “Go on,” she said. “What are you waiting for, Christmas? Scoot.”

The door closed behind us. The back yard was not as nice as the front. It was fenced off in chain link, with wood slats set into it for privacy. One bare tree, staked down with wires, grew in a plot of gravel. A sidewalk along one side led to some garbage cans and a high gate to the alley, padlocked. The wind was shrill and cold. Kerry rubbed at his eyes. I sucked on the collar of my coat for warmth. What were we supposed to do? Not just, what were we supposed to do in the cold yard, but for the whole of a day, or many days, in Mrs. Wojo’s house?

After a while she called us back inside. We took off our shoes at the door, and then we washed our hands in the bathroom. She sat us down at the kitchen table and brought out two glasses of milk and two plates with sandwiches cut into quarters. Kerry and I tried them. They were filled with a thin, fishy paste, and we put them back down again.

“What’s the matter with you?” Mrs. Wojo demanded. She was watching us from the doorway, smoking a cigarette and tapping the ashes into the lid of a jelly jar. “What do we got here, picky eaters?”

“I don’t like it,” I said. I didn’t see any reason not to say so. I was that young. Kerry kept looking at his plate. He was scared for me.

“It’s tuna fish. Don’t tell me you don’t like tuna fish.”

I didn’t know what to say to that. The tuna we had at home was mixed with mayonnaise and sweet pickle relish. This wasn’t the same. “How about milk?” Mrs. Wojo said. “You all right with milk?”

“I like chocolate milk.”

“Do you now,” Mrs. Wojo said, agreeably. She reached the end of her cigarette, put it out in the jar lid, and set the lid on the kitchen counter. “Well, when you’re old enough to get a job and earn money, then you can go buy chocolate milk. If you don’t want to eat, that’s your business. You look like you could miss a few meals and not suffer. You, now—” She stood behind Kerry and patted at his arms and shoulders. “You could use a little fattening up.”

She turned and rummaged around in a cupboard. “Let’s try, ah, peanut butter. A little good old PB and J.”

We watched while she hauled out the peanut butter and jelly, spread slabs of them on bread, cut the sandwich into four pieces, and replaced Kerry’s tuna fish with this new plate. Kerry and I looked at her, waiting. “Where’s mine?” I asked.

“Your what? Your lunch? Sitting right in front of you. If you don’t want to eat it, I can’t make you.”

The telephone rang then. Mrs. Wojo gave us an annoyed look, as if we were the ones interrupting her, and went out into the hall to answer it. Kerry shoved his plate at me. I took half the sandwich and shoved it back. I crammed it into my mouth and Kerry started in on his half. We heard Mrs. Wojo on the phone, her voice delighted and flirty. She said goodbye, in her fake, pleasant voice, and hung up. I wasn’t quick enough, my cheeks still bulging with bread when she came back in. I froze, awaiting my punishment.

“That’s better,” she said to Kerry. “You need to make a habit of cleaning your plate. Get some size on you. As for you, Missy.” She nodded in my direction. “If you don’t like lunch, maybe you’ll have a better appetite for supper.”

Kerry and I traded looks, and I got the rest of the sandwich down as fast as I could.

It was a piece of luck to discover Mrs. Wojo’s weakness right away—namely, she couldn’t see five feet in front of her face.

After lunch we were sent upstairs for naps. “We don’t take naps,” I said, but quietly, under my breath.

“What’s that?”

Mrs. Wojo swung around to face us. She wore capri pants that showed her red, knobby ankles, and a shirt with a pattern of pineapples. I fixed my eyes on them, pineapple pineapple pineapple pineapple, so as not to look at her. “Nothing,” I said.

“Do you two know why you’re here?” We didn’t answer. “Do you?”

We said we did not. “It’s because you have unfit parents.” She paused to let that sink in.

I didn’t know what that meant, unfit. Like clothes fit you?

“The state wants to keep you from turning into juvenile delinquents. That’s why they took you away. You understand?”

We didn’t. She exhaled, and the pineapples billowed in and out. “Now, upstairs, and keep quiet.”

“My daddy says, people should keep their noses on their own faces.”

I thought she would hit me. But she wasn’t a hitter. Instead she gripped my wrist and squeezed hard. “And who’s your daddy? A jailbird? A drug addict?” She released me. My wrist burned for a long time.

Upstairs, Kerry sat on one bed and I took the other. We heard the television going, some show with lots of laughing and applause. We didn’t talk about what Mrs. Wojo had said about our father. It would have made it real. We looked out the window, a dormer at the back of the house. The view was of the yard, and the alley, and the grid of similar small, fenced yards and the houses beyond them. Where was our house? All I knew was you needed a car to get there.

Kerry rubbed at his eyes again. By morning they would be crusted over, and would have to be pried open with a warm washcloth. He said, “You shouldn’t make her mad.”

“I didn’t.” She was already mad. “Is she a witch?”

“There aren’t witches.”

“Are too.” I knew them from television. Mostly they were green-skinned, but not always.

“There aren’t any just walking around.”

“I bet there are.”

The argument didn’t go anywhere. We didn’t have enough energy to keep it up. Pretty soon Kerry fell asleep but I didn’t. I poked around the room and found those things that were meant for children’s entertainment: A set of alphabet blocks. A picture book, The Golden Treasury of Bible Stories. A jigsaw puzzle in a box spilling pieces.

I had to go to the bathroom, so I went down the stairs, as quietly as I could, waiting on each step. I crept past the door to the living room and the back of Mrs. Wojo’s head as she watched her show, smoke rising from her cigarette in a question-mark shape.

I didn’t turn on a light in the bathroom. The green tile and the green plastic curtains over the small window gave everything a drowned, underwater look. I peed and then spent some time investigating the different bottles and jars set out on the sink and tub and the shelf over the toilet. There were a lot of them, as if it took a great many potions and paint pots for Mrs. Wojo to make her natural self presentable to unsuspecting eyes.

I’d shut and latched the door behind me and suddenly there was a terrific rattling and commotion, Mrs. Wojo on its other side. “Open the door this instant!”

Fright made me clumsy with the latch. When I did manage

it, the door

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...