- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Senator Tim Scott knows adversity. As the son of a single mother from North Charleston, South Carolina, he struggled to get through school and had his dreams of a college football career shattered by a car wreck. But thanks to his mother and a few mentors along the way, he learned that "failure isn't failure unless you quit." He also learned that it's hard work and perseverance, not a government handout, that will get you ahead in life.

Today, Senator Scott is the only black Republican in the Senate, and he believes that investment and commerce are the best ways to rebuild our most impoverished communities. This is the idea behind his signature piece of legislation, the "opportunity zones" program, which President Trump has strongly endorsed. The program provides tax incentives for businesses that invest in low-income urban areas, seeking to replace things like welfare and government assistance.

In Opportunity Knocks, Senator Scott will tell his life story with a focus on adversity and opportunity. He will teach readers about the principles of hard work and hope while addressing the dangers of veering too far toward socialist policies. The book will also not shy away from discussions of racism and racial inequality in the United States and will recount some of Senator Scott's own brushes with racism as well as the many discussions he's had with people who want to help, including President Trump.

Release date: August 5, 2014

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 544

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

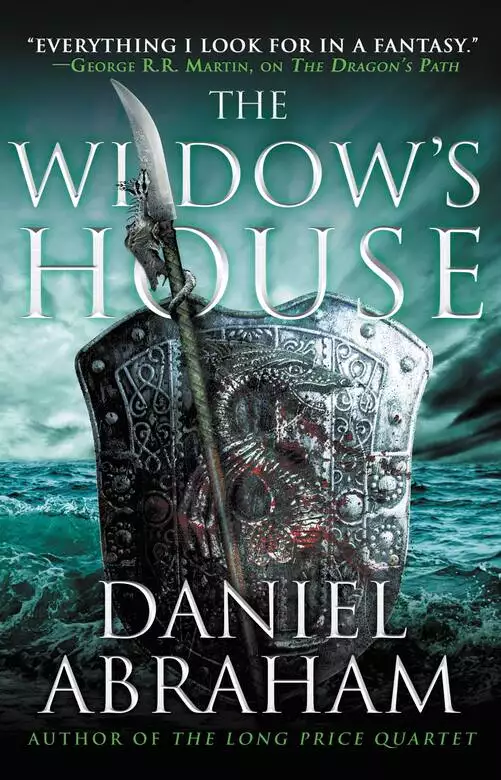

The Widow's House

Daniel Abraham

The mattress she lay on was white as well, and filled with down. The blankets pulled up to her breasts were soft wool, rich with the scent of cedar to keep away moths and now also of sex. They had been packed away for the winter season when the court was all gone from the city, and unpacked now in secrecy. Vincen Coe, the young huntsman who had once been her servant and then her lover and now both, lay spent. His long hair spread around his head like a rich auburn halo, and his breath was deep and soft. Clara Kalliam shifted, using her arm as a pillow, and considered the young man’s face. The improbably long eyelashes, the soft lips, the dark scattering of whiskers just under the surface of his cheek. He was a beautiful man. Young enough to be her son. A thousand ranks below her socially. Devoted to her in a way no man in her life had ever been, except her husband.

A pigeon fluttered up against the dormer’s glass, cooed in confusion, and flew away again. Clara let her body sink into the mattress, enjoying the warmth and softness and languor of her muscles.

She was not a young woman. Her hair was going white. Her skin not so taut as it had been when she was a girl. Vincen was the second man she’d lain with in her whole life, but she tried not to let her greed of him overwhelm her. A lifetime in the vicious meat-grinder of court politics had taught her that there were a thousand different reasons why people had affairs. To satisfy vanity, or for revenge, or out of sorrow. From political necessity or love of scandal. To create the story of one’s self. Or to retell it differently.

She had never imagined herself as the sort of woman to conduct an illicit liaison. And even now, and despite all evidence, she didn’t. Not really. Vincen was simply Vincen, and the woman she was with him, the woman who had risen from the ashes of her husband’s failure and execution, who had lived in a cheap boarding house and been questioned by the regent’s private inquisitors, was more real than the sugar-and-plaster woman she pretended among the court. But, of course, both were true. Her soul encompassed both of them.

“We should go,” Vincen said. “We’ll be missed.”

“We should,” she agreed.

Neither of them moved to reclaim their clothes, strewn on the white floorboards. Their intimate ritual was not done yet. The words were only the prelude to their parting. She breathed in, savoring the dust-smell of the attic and the chill of the air. Through the window, she could see the great tower of the Kingspire rising above the city. Even with the mattress on the floor, the spire’s uppermost floors were too high to see. Only the red banner with its eightfold sigil, the sign and symbol of the spider goddess’s temple housed in its high halls. The cloth shifted in the wind as if it were not only a religious cult’s marking but the new banner of Imperial Antea. Perhaps it was.

“Are things well?” she asked.

“As well as can be,” Vincen said. “I’m still a new man in an established house. It will be some time before I’m trusted. There was some resentment of Jorey.”

“Of Jorey?” she said, her heart moving instantly to her son’s defense. “Whatever for?”

“He married Lord Skestinin’s daughter just in time to make her the daughter-in-law of a traitor.”

“Oh. Well, yes. That.”

“Now that he’s better known as the regent’s right hand than his father’s son, it’s turning about, though.”

Clara considered the rafters. A spider’s web clung in a corner, empty. In the course of three seasons, she had gone from the Baroness of Osterling Fells to the disgraced wife of a traitor to the mother of the new Lord Marshal. And in among all of those, she’d become a widow and a fallen woman, a traitor to the crown in her own right and a patriot more devout than most of the men who had the running of the empire. The court had left her in the autumn a woman barely rehabilitated, her very name tainted. When they returned, they would find themselves jockeying to be in her good graces. It left her dizzy when she thought about it, like looking up at the stars.

“Things change so quickly,” she said, “and so completely.”

“They don’t, m’lady,” Vincen said, taking her hand. He kissed the knuckle of her thumb. “Only the stories we tell about them do.”

The dreaded moment came when Clara sighed and pulled the blanket aside. Knowing in the mornings that she might hope for these brief hours, she had adjusted her wardrobe to those garments she could put off and on with only minimal assistance from her servants or Vincen. She painted her face only lightly these days. When she’d lived in the boarding house, she had forgone the practice entirely. She descended from their hidden nest first, making her way by the central stair to the third-floor rooms, some of which were her own. Sabiha and Jorey’s marital apartments were on the same floor, near the street. Lower down, the guest rooms and the private quarters of Lord and Lady Skestinin, who very rarely used them. He was more often away with the fleet or at his holdings in Estinport, and she was famously allergic to the politics of the court. And likely wiser and more content because of it.

But as a result, the household in Camnipol was small. Its gardens were insignificant, and it hardly commanded more land than it took to place the house. Even the kitchens and stables were small, as if added as an afterthought. The house belonged to the commander of the Imperial Navy. Jorey Kalliam resided there now as the new Lord Marshal, with his brother Vicarian and his mother, Clara. Other estates in the city might boast more wealth and more beautiful grounds, but none had the military power of the empire in so concentrated a form. Except, of course, for the Kingspire.

“It seems like we do this every day.” Vicarian’s voice came from Jorey’s private study. The tone was on the knife edge between amused and annoyed, as it so often was with her boys. “You panic, you come to me, and I talk sense into you. We settle matters, and then as soon as I walk out of the room, you start working yourself back into a lather.”

“I go back to look at the numbers again,” Jorey said, his tone almost of apology. “They are frightening damned numbers, for what that’s worth.”

“They don’t matter. We didn’t win the wars on the back of numbers. Antea is chosen of the goddess. We’re going to win.”

“With exhausted men, a season’s planting that’s relying on the labor of recently captured slaves, and twice as much land to hold as we had a year ago, it seems that we’ve put upon the kindness of the goddess plenty long enough.”

“You don’t understand,” Vicarian said. “She will not let us lose.”

In the half dozen steps from the middle of the staircase to its end, Clara felt her body change as she adopted her role. Her chin rose and a polite smile took its accustomed place upon her lips. Decades she had not felt only minutes before settled on her like a shawl made from dust. She was the mother of grown men now, a widow, and—though her precise status would give etiquette masters belly knots—a woman of the court. She stepped into Jorey’s study with an arched eyebrow.

“I can’t help noticing that my boys are shouting at each other again,” she said, teasing. “Surely we can solve the complex problems of the empire in a civil tone of voice.”

Vicarian rose from his divan, smiling. Ever since he’d returned from the new temple within the Kingspire, his priestly robes included the swatch of red and the eightfold sigil, and there was a brightness in his eyes that reminded Clara of men taken by fever. It saddened her to see it, but she pretended it wasn’t there. He was lost to her now, but she could pretend he would return one day.

“It’s Jorey, Mother,” Vicarian said. “He’s seen the power of the goddess time after time, but he has a doubter’s heart. Come. Help me fix him.”

Vicarian took her hand and kissed her cheek. His flesh seemed warmer than the fire muttering in the grate could account for.

“I don’t believe I’ve had authority over Jorey’s heart for some time,” Clara said. “Though it is sometimes pleasant to pretend otherwise. What seems to be the trouble?”

“It’s the war,” Jorey said, as a farmer might have said, It’s the crops. “Ternigan’s death leaves everything in a muddle.”

Clara smiled. That her plot against Ternigan had borne fruit almost compensated for the fact that it had put Jorey in the old Lord Marshal’s place. Before that, she’d sent anonymous letters out, reporting on the plans and ambitions of the regent to his enemies as best she could from her diminished position. So far as she could see, it had been as effective as flinging pebbles into the Division. Tempting Ternigan into treason with forged letters and false promises had deprived the army of one of its most experienced minds, she was glad to hear. That it left her still uncertain how to unseat Geder Palliako and his spider priests without unmaking the empire as a whole could only be expected. You can’t make a rug from a single knot, as her mother used to say.

“The muddle being?” Clara asked.

“Most of the army sitting in the freezing mud outside Kiaria has been fighting for at least a year,” Jorey said. “Some of them haven’t seen rest since before Asterilhold. I have to go take command of the siege—”

“Which we should have done a week ago,” Vicarian said.

“—but I don’t know what to do with them. On one hand, putting a holding force outside Kiaria invites the Timzinae to try to break out. On the other, Father always said wars were won and lost over cookfires, and when I look at the supply reports, pushing on seems like begging the army to break.”

“They won’t break,” Vicarian said. “The goddess won’t let us lose. Look at all of the things that we shouldn’t have won already. The battle at Seref Bridge? Father should have lost that. Would have, if he hadn’t had the priests. And when the Timzinae turned him against the throne, he also went against the goddess, and he lost. How many people said we might—might—take Nus by winter. And we took Nus, Inentai, Suddapal, and we’re camped outside Kiaria. We wouldn’t have stopped Feldin Maas without Geder bringing Minister Basrahip from the temple. According to your numbers, we should have lost already half a dozen times over, and we didn’t. And we won’t. I keep telling you that.”

“And after you’ve said it five or six times, it even starts seeming plausible,” Jorey said. “But I sleep on it, and in the morning—”

“My lords,” the steward said. He was a Dartinae, and the glow of his eyes made his expression difficult to read. It seemed to Clara that he was excited. Or frightened. “The Lord Regent has arrived.”

Clara and her sons went silent. The man could as well have announced that the Division had closed. It would have been as plausible.

“The Lord Regent is in the south,” Jorey said. “Geder wrote that he was going to Suddapal. To get here from there, he’d have had to ride almost straight through.”

“I’ve put him in the western withdrawing room,” the steward said with a bow.

A cold dread moved down Clara’s spine. There were stories, of course, of Geder Palliako’s uncanny abilities. That the spirits of the dead rose up to march alongside the armies of Antea. That King Simeon pushed open his tomb to consult with the regent. To listen to all the tales, Geder Palliako was more than a cunning man. Of course, there were also stories that her fallen husband, Dawson, had been the puppet of foreigners and Timzinae, so there was only so much credence such things could bear. Still, as she walked arm in arm with Jorey, her mind was plagued by a sense of dark miracles just beyond her sight. Perhaps Geder was in Suddapal and Camnipol both. Perhaps distance had ceased to have meaning for him.

Or perhaps he’d simply ridden straight through.

Clara had known half a dozen aspects of Geder Palliako, from the awkward boy lost in the complexity of court etiquette to the frenzied executioner of her own husband, slaughtered before her eyes. He had stood over her as half-demonic judge and by her side as an ally against armed foes. He was a violent and unpredictable man, and she feared and opposed him as she would a wildfire or a plague.

The thin, ill-looking being on the divan looked up at them as they stepped in the room. His hair was lank and unwashed. His eyes were puffy and red. He rose to his feet slowly, as if in pain. When he spoke, his voice was thick with tears.

“Jorey. I’m sorry. I didn’t know where else to go,” the Lord Regent of Imperial Antea said. “I don’t have anyone I can talk to. So I came here. I’m sorry if I’m getting in the way.”

“Geder?” Jorey said, stepping toward the man. “Are you ill? You look…”

“I know. I look like hell,” Geder said, then nodded to Clara. “Lady Kalliam. I’m sorry.”

You murdered my husband with a dull blade and apologize to me for looking unwell, she thought. “Lord Regent,” she said.

“I thought you were in Suddapal. With…” Jorey glanced at her, embarrassment showing for a moment in his eyes. “With your banker… woman… friend.”

“Cithrin betrayed me,” Geder said, his lips shuddering with the words. Bright tears spilled down his cheeks. “I told her that I loved her, just the way you said, and that I wanted her. And I told Fallon Broot that she and her bank shouldn’t be interfered with and she…” Geder sobbed, staring at Jorey like a child with a favorite toy that had broken in his hands. “She worked with the Timzinae. And when I went to her, she left. She was gone when I came. I loved her, Jorey. I’ve never loved anybody.”

Clara nodded to Geder and then to Jorey, and stepped slowly backward out of the room, drawing the door almost closed behind her. Almost, but not quite. She stood in the corridor, her head bowed, and listened as the most powerful man in the world, hero and regent and unquestioned leader of the empire, poured out confessions of heartbreak between sobs. Clara knew the name Cithrin. There had been a part-Cinnae girl, pale as a sprout and as fragile, who’d come to Camnipol in some previous age, when Dawson still lived. Clara recalled the girl offering condolences after Dawson’s execution like it had been some particularly vivid dream. Cithrin bel Sarcour, assistant or some such to Paerin Clark of the Medean bank.

The same Paerin Clark to whom she had been sending her letters. She turned away, walking down the corridor on cat-soft feet. A thousand questions buzzed in her mind. What did the bank know? What did it suspect? What was its agenda in undermining Geder’s plans to enslave the Timzinae? Some answers she could glean from listening to her boys talk in the morning. Others she might have to take her best guess and be satisfied. When she regained her own rooms, she sent the servant girl away and lay on her bed, her arms spread wide, and laughed silently. It wasn’t mirth that shook her, but relief and fear.

The sun fell, turning her windows to red and then grey and then black. She lit her little bedside lamp herself and called for a servant to set a fire in the grate. She had her supper brought to her—beet soup and a thin shank of chicken. Hardly the sumptuous repast she was used to seeing in the houses of the powerful, but a thousand times better than what she would have had in the boarding house. And times, after all, were hard. Afterward, she lit her pipe and waited, her mind moving in silence.

Vincen came near midnight, his soft cough outside her door as deliberate as an announcement. She let him in and closed the door behind him. The warmth of sexuality and love was gone from his expression. And from hers.

“Well,” she said. “I think we have the scandal of the season, and the court not even returned from the King’s Hunt.”

“Does he know, then? Does the Lord Regent suspect you?”

Clara drew fresh smoke into her lungs, frowning. “I’m not in prison or dead, so I doubt it. And why should he?”

“This can’t be good, m’lady.”

“It may not be. Or it may be excellent. Until now Geder has stepped from success to success. Even his failures have been recast as master strategy after the fact. This is a humiliation, and what’s more, a romantic one. If there’s anything Geder understands less than war, it’s love. It isn’t a picture that can be made lovely by a different frame.”

“He won’t lose power over it. If anything, people will see him with greater sympathy.”

“Worse than sympathy. Pity. The hero of Antea will be remade as a victim. And I will wager you anything you like that Geder will take comfort in it. He is entirely too ready to point out the ways in which he’s been wronged, when what he ought to do is make light of it.”

“So this… is a good thing?”

“You’re the one that said it. It isn’t we who change, but the stories about us. This will make him less a creature of awe. Less the great man from legend. It may remind the noble houses that Geder and his priests are capable of losing, and if it does, that will be a very fine thing indeed,” Clara said. Her tobacco was spent, and she leaned forward, tapping the ashes out into the fire. “I feel sorry for the girl, though. She’s done us a favor, and for payment, she’s about to become the most hated woman in the world.”

The sea had never been home for Cithrin bel Sarcour. Her life had been grown around the Medean bank as a vine around a trellis, and so the great waters of the world had been one part roadway that linked all ports and one part supplier of fish and salt and oil. Vaster than the lands on her maps, the sea had been defined by where it connected and what could be taken from it. That it was also a place had never entered her mind before now.

The winter days spent on the Inner Sea were brief, bright, and cold. The nights were black. Ice coated the decks and frost formed on the rigging by moonlight, melting only reluctantly with the coming of dawn. The shore was a darkness on the northern horizon, and Cithrin looked at it from the rails wishing she might never touch land again. Behind her little ship was the wreckage of the five cities of occupied Suddapal. Before her, Porte Oliva. One, a city that had fallen to the murderous ambitions of Antea. The other, her home. And somewhere beyond the black line to the north was Geder Palliako, regent of Antea and leader of the spider priests, whom—for the best of reasons—she had embarrassed and betrayed. Every hour brought her closer to the docks of Porte Oliva and the necessity of facing the consequences of her choice. She would rather have stayed at sea.

Instead, she spent her days walking the decks and her nights in her tiny cabin, a plank across her thighs, writing and rewriting her report to the bank. She had left Suddapal with no warning, and was traveling so quickly that no courier would outpace her. The news of her decision to abandon the city and their efforts there would arrive with her. The ledgers and books in the chest under her hammock would tell the whole tale, but her report was her chance to interpret it, to shape for the others what she had been thinking and why she had done what she’d done. Every night she tried, and every morning scraped the ink from the parchment and began again until the morning came with no more nights behind it.

Yardem Hane, the head of her guard company now that Marcus Wester was gone, stood on the deck at her side. His great ears were cocked forward, as if he were listening to the waves. She pulled her black wool cloak tight around her shoulders and let the wind bite at her face. The smoke from Porte Oliva’s chimneys rose in the north, white against the winter blue.

“Well,” she said, “this will be interesting.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Yardem said, his voice low and rolling as a landslide. “Afraid it will.”

The call of seagulls grew slowly louder as the captain angled the ship in toward shore. “I did what needed to be done.”

“Did.”

“You’d think that would be comforting.”

He turned his wide, canine head to her. “Regrets, ma’am?”

“Ask me again when I’ve made my report.”

The seawall of Porte Oliva rose up high above the surf. As the guide boat led them in through the maze of reefs that made up the bay, Cithrin considered the stone. At the top, narrow openings showed where engines of war could be placed should the city come under siege. She had walked by them a thousand times, and only seen them as a curiosity of the architecture. The world had changed.

Once they reached the docks, she paid the captain his fees and greeted the harbormaster’s assistant. The docking taxes were a simple formality, quickly assessed and quickly paid. Yardem and Enen saw to the unloading of the cargo: crates and chests, and the last few Timzinae citizens whom Cithrin had been able to bring with her. Most were children, some barely old enough to walk, sent to a city where they might know no one rather than remain in their homes and be used to force the compliance of their parents. Those who had no one to meet, Yardem rounded up, instructing them to hold each other’s hands, to watch for each other, and be sure no one was lost. The sight left Cithrin on the edge of tears.

“To the counting house, Magistra?” Enen asked.

“Not yet,” Cithrin said. “You go ahead of me. I think I’ll spend a moment with the city first.”

“Would you like me to deliver your report to Pyk?”

“Yes, if you’d be so kind,” Cithrin said. “It’s in the chest with the books and ledgers there. If Magistra Isadau is there…”

Enen smiled, compassion softening her grey-pelted face. Odd to think there was a time Cithrin had found the Kurtadam woman’s expressions difficult to read.

“I’ll tell her you’re looking forward to seeing her, ma’am,” the old guard said, nodding her head.

Cithrin had come to Porte Oliva as a refugee too young to own property or sign contracts. She had relied for her survival on the protection of men of violence like Yardem Hane and Marcus Wester, the counsel of professional deceivers like Master Kit and Cary and poor, dead Opal, and the training she had in matters of finance that taken the place of love in her childhood. Then, she had needed training to know how to walk as woman walked, and not a girl. Since, she had seen a slaughtered priest hung before his church, had lived in hiding while an insurrection wracked the city around her, had prepared to debase herself in the name of saving others and found that she could not. She no longer needed to remind herself to hold her weight low in her hips or to pull her shoulders back. She walked through the familiar streets of Porte Oliva as if she were older than her years because it was true now. She had become the woman she’d only pretended to be, and the weight of it was more than she’d anticipated.

Porte Oliva had always been a place where the thirteen races of humanity mixed. Otter-pelted Kurtadam with the ornamental beads worked into their fur. Thin, pale Cinnae moving through the streets like ghosts. Bronze-scaled Jasuru, thick-featured Firstblood. There were even a handful of Tralgu and Yemmu, though Cithrin had rarely seen them apart from Yardem and Pyk Usterhall. And the Drowned swam in lazy pods through the water of the bay. She had spent so much time and effort sneaking Timzinae away from Suddapal that she’d expected to see the mixture on the streets of Porte Oliva changed. It was not. There were some Timzinae as there always had been, but she could not say it was more, and after almost a year in Elassae, they seemed too few.

At the southern edge of the Grand Market, she stopped for a while, bought a cup of honeyed almonds from a street cart, and watched one of the puppet shows that made up the civic dialogue. It was a retelling of the classic story of the rise of Orcus the Demon King, with the plot and dialogue changed. The Orcus puppet was in the shape of a Firstblood man in a flowing black cloak, and when the puppeteer spoke his words, they had the accent of Imperial Antea. Geder Palliako’s reputation had spread even to here, then, and Cithrin was not the only one who looked on his victories with dread. The war that the wise had said would never spread so far or last so long had swamped her. The soldiers and the priests had not come here—not yet—but the fear of them had. She wasn’t sure if that left her saddened or pleased. Either way, it was good that they knew.

She left before the end of the show, dropping a silver coin in the box at the puppeteer’s feet, and passed through the Grand Market. The riot of stalls and sellers shouting each other down washed around her, and she felt herself relax a degree for the first time since she’d stepped off the ship. At one stall, a man was selling expensive dresses with the weeping colors of Hallskari salt dye, and she smiled at them.

Banking and commerce were a dance of information and deception, lies and facts and all the power that gold could provide, and she knew it better than she knew herself. She had seen it in the houses of Suddapal, the courts of Camnipol, the theater cart of Master Kit’s traveling company. The Grand Market of Porte Oliva was the expression of it that was most her own. If she chose, she could see it as an innocent might. Men and women jostling one another, merchants in their stalls calling or haggling or adjusting their wares. The queensmen in green and gold strolling through the chaos with bored expressions. Cithrin could see all of that, but she could also see more. The way the price of a bottle of wine in one stall rose when the competitor across the market was too busy to call out a lower one. The way that a bag of coffee was priced ridiculously high so that the bag beside it could be merely exorbitant and still seem a bargain. She could track cutpurses and unlicensed fortune tellers moving in response to the queensmen, finding the balance between turning a profit and ending in a cage outside the Governor’s Palace, measuring their chances in feet from the law, in the degrees by which their faces and shoulders were turned away. Cithrin could look at the placement of the stalls, drawn by random lot at the beginning of each day, and see who had bribed the queensmen who controlled the lottery box. The state of the city was written in the chaos like an expression on a well-known face.

She stepped out the main entrance to the market and into the square beyond it feeling calmer. But only a little bit. The distraction was pleasant, but it did nothing to change the facts of her situation. That accounting would come soon enough. She nodded to the head of the guard as she passed, and he nodded back.

“Good to see you again, Magistra,” he said. “Didn’t know you’d come back.”

“I’ve only just arrived,” she said.

“City’s not been the same without you.”

“Flatterer,” Cithrin said and walked on.

So far as anyone knew, she was and had always been the authorized voice of the Medean bank in Porte Oliva. That she had been underaged when she founded the bank, that the documents of foundation were forgeries, that her notary, the de-tusked Yemmu woman called Pyk Usterhall, was the true authorized power of the branch were all secrets. Another example of the banker’s trade of seeming one thing and being another.

She pushed through the front doors of the café and shrugged off her cloak. The smell of the fresh coffee and cinnamon, bread and black vinegar were like coming home.

“Magistra!” the ancient Cinnae man said, his straw-thin, straw-pale fingers splayed in the air, his grin warm.

“Maestro Asanpur,” she said, accepting his embrace. “I’m so glad to see you again.”

“Come, sit. I will bring you your usual, eh?”

The café had been her idea. Maestro Asanpur was a Cinnae, as her own mother had been. The ancient man with the one milky eye and the touch for coffee that bordered on a cunning man’s art had been happy enough to rent her the use of a back room. The café had become her unofficial office. The center of a bank that held its business in the centers of power all across the world. Or that had, when the world had been a better place. Before Vanai burned. Before Suddapal fell. Maestro Ansanpur put the bone-colored cup in front of her. The coffee was sweeter than it had been in Suddapal, more gentle. Softened with milk and left simple compared with the complex spices the Timzinae used in the country that had been their home. Sipping it was like being two different people—the woman who during her months of exile had longed for the familiar comforts, and also the traveler to whom this particular comfort was no longer familiar. Asanpur stood at her side, his hands fluttering restlessly at his hip, his face open and bright, waiting for her approval.

Cithrin closed her eyes in pleasure that was only half feigned. “It’s good to be home.”

The old man beamed with pleasure and went back to his kitchens. Cithrin sat quietly, waiting for her body to stop telling her that the ground beneath her was shifting with the w

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...