The Potter of Bones

ELEANOR ARNASON

Eleanor Arnason published her first novel, The Sword Smith, in 1978, and followed it with such novels as Daughter of the Bear King and To the Resurrection Station. In 1991, she published her best-known novel, one of the strongest novels of the nineties, the critically-acclaimed A Woman of the Iron People, a complex and substantial novel which won the prestigious James Tiptree Jr. Memorial Award. Her short fiction has appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Amazing, Orbit, Xanadu, and elsewhere. Her other books include Ring of Swords and Tomb of the Fathers, and a chapbook, Mammoths of the Great Plains, which includes the eponymous novella, plus an interview with her and a long essay, and a collection, Big Mama Stories. Her story “Stellar Harvest” was a Hugo Finalist in 2000. Her most recent books are two new collections, Hidden Folk: Icelandic Fantasies, and a major SF retrospective collection, Hwarhath Stories: Transgressive Tales by Aliens. She lives in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Here she takes us to a strange planet sunk in its own version of a medieval past for a fascinating study of the birth of the Scientific Method … and also for an intricate, moving, and quietly lyrical portrait of a rebellious and sharp-minded woman born into a time she’s out of synch with and a world that refuses to see what she sees all around her.

The northeast coast of the Great Southern Continent is hilly and full of inlets. These make good harbors, their waters deep and protected from the wind by steep slopes and grey stone cliffs. Dark forests top the hills. Pebble beaches edge the harbors. There are many little towns.

The climate would be tropical, except for a polar current which runs along the coast, bringing fish and rain. The local families prosper through fishing and the rich, semi-tropical forests that grow inland. Blackwood grows there, and iridescent greywood, as well as lovely ornamentals: night-blooming starflower, day-blooming skyflower and the matriarch of trees, crown-of-fire. The first two species are cut for lumber. The last three are gathered as saplings, potted and shipped to distant ports, where affluent families buy them for their courtyards.

Nowadays, of course, it’s possible to raise the saplings in glass houses anywhere on the planet. But most folk still prefer trees gathered in their native forests. A plant grows better, if it’s been pollinated naturally by the fabulous flying bugs of the south, watered by the misty coastal rains and dug up by a forester who’s the heir to generations of diggers and potters. The most successful brands have names like “Coastal Rain” and emblems suggesting their authenticity: a forester holding a trowel, a night bug with broad furry wings floating over blossoms.

This story is about a girl born in one of these coastal towns. Her mother was a well-regarded fisherwoman, her father a sailor who’d washed up after a bad storm. Normally, a man such as this—a stranger, far from his kin—would not have been asked to impregnate any woman. But the man was clever, mannerly and had the most wonderful fur: not grey, as was usual in that part of the world, but tawny red-gold. His eyes were pale clear yellow; his ears, large and set well out from his head, gave him an entrancing appearance of alertness and intelligence. Hard to pass up looks like these! The matrons of Tulwar coveted them for their children and grandchildren.

He—a long hard journey ahead of him, with no certainty that he’d ever reach home—agreed to their proposal. A man should be obedient to the senior women in his family. If they aren’t available, he should obey the matrons and matriarchs nearby. In his own country, where his looks were ordinary, he had never expected to breed. It might happen, if he’d managed some notable achievement; knowing himself, he didn’t plan on it. Did he want children? Some men do. Or did he want to leave something behind him on this foreign shore, evidence that he’d existed, before venturing back on the ocean? We can’t know. He mated with our heroine’s mother. Before the child was born, he took a coastal trader north, leaving nothing behind except a bone necklace and Tulwar Haik.

Usually, when red and grey interbreed, the result is a child with dun fur. Maybe Haik’s father wasn’t the first red sailor to wash up on the Tulwar coast. It’s possible that her mother had a gene for redness, which finally expressed itself, after generations of hiding. In any case, the child was red with large ears and bright green eyes. What a beauty! Her kin nicknamed her Crown-of-Fire.

When she was five, her mother died. It happened this way: the ocean current that ran along the coast shifted east, taking the Tulwar fish far out in the ocean. The Tulwar followed; and somewhere, days beyond sight of land, a storm drowned their fleet. Mothers, aunts, uncles, cousins disappeared. Nothing came home except a few pieces of wood: broken spars and oars. The people left in Tulwar Town were either young or old.

Were there no kin in the forest? A few, but the Tulwar had relied on the ocean.

Neighboring families offered to adopt the survivors. “No thank you,” said the Tulwar matriarchs. “The name of this bay is Tulwar Harbor. Our houses will remain here, and we will remain in our houses.”

“As you wish,” the neighbors said.

Haik grew up in a half-empty town. The foresters, who provided the family’s income, were mostly away. The adults present were mostly white-furred and bent: great-aunts and -uncles, who had not thought to spend their last years mending houses and caring for children. Is it any wonder that Haik grew up wild?

Not that she was bad; but she liked being alone, wandering the pebble beaches and climbing the cliffs. The cliffs were not particularly difficult to climb, being made of sedimentary stone that had eroded and collapsed. Haik walked over slopes of fallen rock or picked her way up steep ravines full of scrubby trees. It was not adventure she sought, but solitude and what might be called “nature” nowadays, if you’re one of those people in love with newfangled words and ideas. Then, it was called “the five aspects” or “water, wind, cloud, leaf and stone.” Though she was the daughter of sailors, supported by the forest, neither leaf nor water drew her. Instead, it was rock she studied—and the things in rock. Since the rock was sedimentary, she found fossils rather than crystals.

Obviously, she was not the first person to see shells embedded in cliffs; but the intensity of her curiosity was unusual. How had the shells gotten into the cliffs? How had they turned to stone? And why were so many of them unfamiliar?

She asked her relatives.

“They’ve always been there,” said one great-aunt.

“A high tide, made higher by a storm,” said another.

“The Goddess,” a very senior male cousin told her, “whose behavior we don’t question. She acts as she does for her own reasons, which are not unfolded to us.”

The young Tulwar, her playmates, found the topic boring. Who could possibly care about shells made of stone? “They don’t shimmer like living shells, and there’s nothing edible in them. Think about living shellfish, Haik! Or fish! Or trees like the ones that support our family!”

If her kin could not answer her questions, she’d find answers herself. Haik continued her study. She was helped by the fact that the strata along the northeast coast had not buckled or been folded over. Top was new. Bottom was old. She could trace the history of the region’s life by climbing up.

At first, she didn’t realize this. Instead, she got a hammer and began to break out fossils, taking them to one of the town’s many empty houses. There, through trial and error, she learned to clean the fossils and to open them. “Unfolding with a hammer,” she called the process.

Nowadays we discourage this kind of ignorant experimentation, especially at important sites. Remember this story takes place in the distant past. There was no one on the planet able to teach Haik; and the fossils she destroyed would have been destroyed by erosion long before the science of paleontology came into existence.

She began by collecting shells, laying them out on the tables left behind when the house was abandoned. Imagine her in a shadowy room, light slanting through the shutters. The floor is thick with dust. The paintings on the walls, fish and flowering trees, are peeling. Haik—a thin red adolescent in a tunic—bends over her shells, arranging them. She has discovered one of the great pleasures of intelligent life: organization or (as we call it now) taxonomy.

This was not her invention. All people organize information. But most people organize information for which they can see an obvious use: varieties of fish and their habits, for example. Haik had discovered the pleasure of knowledge that has no evident use. Maybe, in the shadows, you should imagine an old woman with white fur, dressed in a roughly woven tunic. Her feet are bare and caked with dirt. She watches Haik with amusement.

In time, Haik noticed there was a pattern to where she found her shells. The ones on the cliff tops were familiar. She could find similar or identical shells washed up on the Tulwar beaches. But as she descended, the creatures in the stone became increasingly strange. Also, and this puzzled her, certain strata were full of bones that obviously belonged to land animals. Had the ocean advanced, then retreated, then advanced again? How old were these objects? How much time had passed since they were alive, if they had ever been alive? Some of her senior kin believed they were mineral formations that bore an odd resemblance to the remains of animals. “The world is full of repetition and similarity,” they told Haik, “evidence the Goddess has little interest in originality.”

Haik reserved judgment. She’d found the skeleton of a bird so perfect that she had no trouble imagining flesh and feathers over the delicate bones. The animal’s wings, if wings they were, ended in clawed hands. What mineral process would create the cliff top shells, identical to living shells, and this lovely familiar-yet-unfamiliar skeleton? If the Goddess had no love for originality, how to explain the animals toward the cliff bottom, spiny and knobby, with an extraordinary number of legs? They didn’t resemble anything Haik had ever seen. What did they repeat?

When she was fifteen, her relatives came to her. “Enough of this folly! We are a small lineage, barely surviving; and we all have to work. Pick a useful occupation, and we’ll apprentice you.”

Most of her cousins became foresters. A few became sailors, shipping out with their neighbors, since the Tulwar no longer had anything except dories. But Haik’s passion in life was stone. The town had no masons, but it did have a potter.

“Our foresters need pots,” said Haik. “And Rakai is getting old. Give me to her.”

“A wise choice,” said the great-aunts with approval. “For the first time in years, you have thought about your family’s situation.”

Haik went to live in the house occupied by ancient Rakai. Most of the rooms were empty, except for pots. Clay dust drifted in the air. Lumps of dropped clay spotted the floors. The old potter was never free of the material. “When I was young, I washed more,” she said. “But time is running out, and I have much to do. Wash if you want. It does no harm, when a person is your age. Though you ought to remember that I may not be around to teach you in a year or two or three.”

Haik did wash. She was a neat child. But she remembered Rakai’s warning and studied hard. As it turned out, she enjoyed making pots. Nowadays, potters can buy their materials from a craft cooperative; and many do. But in the past every potter mined his or her own clay; and a potter like Rakai, working in a poor town, did not use rare minerals in her glazes. “These are not fine cups for rich matrons to drink from,” she told Haik. “These are pots for plants. Ordinary glazes will do, and minerals we can find in our own country.” Once again Haik found herself out with hammer and shovel. She liked the ordinary work of preparation, digging the clay and hammering pieces of mineral from their matrices. Grinding the minerals was fine, also, though not easy; and she loved the slick texture of wet clay, as she felt through it for grit. Somehow, though it wasn’t clear to her yet, the clay—almost liquid in her fingers—was connected to the questions she had asked about stone.

The potter’s wheel was frustrating. When Rakai’s old fingers touched a lump of clay, it rose into a pot like a plant rising from the ground in spring, entire and perfect, with no effort that Haik could see. When Haik tried to do the same, nothing was achieved except a mess.

“I’m like a baby playing with mud!”

“Patience and practice,” said old Rakai.

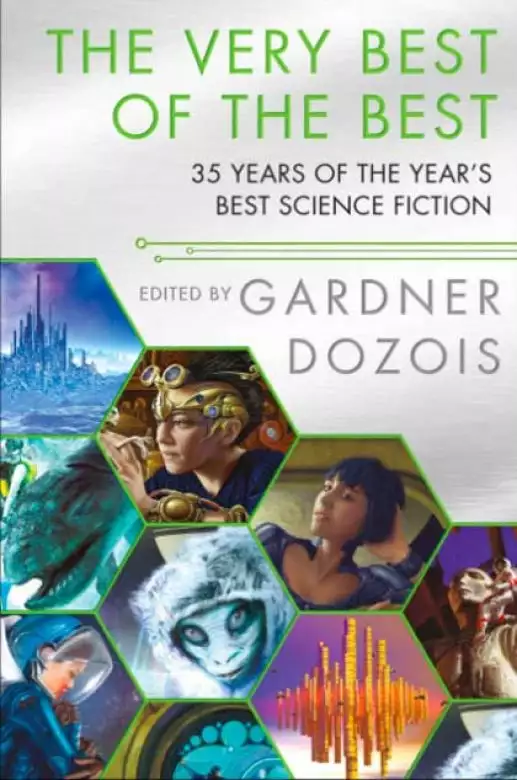

Copyright © 2019 by Gardner Dozois

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved