- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

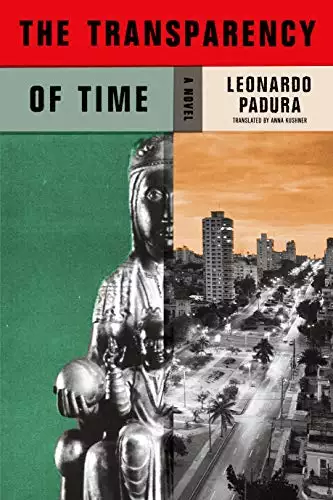

From Leonardo Padura—whose crime novels featuring Detective Mario Conde form the basis of Netflix’s Four Seasons in Havana—The Transparency of Time sees the Cuban investigator pursuing a mystery spanning centuries of occult history.

Mario Conde is facing down his sixtieth birthday. What does he have to show for his decades on the planet? A failing body, a slower mind, and a decrepit country, in which both the ideals and failures of the Cuban Revolution are being swept away in favor of a new and newly cosmopolitan worship of money.

Rescue comes in the form of a new case: an old Marxist turned flamboyant practitioner of Santería appears on the scene to engage Conde to track down a stolen statue of the Virgen de

Regla—a black Madonna. This sets Conde on a quest that spans twenty-first century Havana as well as the distant past, as he delves as far back as the Crusades in an attempt to uncover the true provenance of the statue.

Through vignettes from the life of a Catalan peasant named Antoni Barral, who appears throughout history in different guises—as a shepherd during the Spanish Civil War, as vassal to a feudal lord—we trace the Madonna to present-day Cuba. With Barral serving as Conde’s alter ego, unstuck in time, and Conde serving as the author’s, we are treated to a panorama of history, and reminded of the impossibility of ever remaining on its sidelines, no matter how obscure we may think our places in the action.

Equal parts The Name of the Rose and The Maltese Falcon, The Transparency of Time cements Leonardo Padura’s position as the preeminent literary crime writer of our time.

Release date: June 15, 2021

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Transparency of Time

Leonardo Padura

SEPTEMBER 4, 2014

The emphatic first light of dawn in the tropics filtered through the window, projecting dramatically against the wall where the calendar hung, with its perfect grid of twelve squares divided into four rows. The spaces had originally been colored in distinctive tones ranging from spring’s youthful green to winter’s deep gray, a scheme that only a very imaginative designer could associate with something as contrived as the four seasons on a Caribbean island. With the passing months, fly droppings had decorated the board’s motifs with erratic ellipses. Several stains and its ever-fading colors testified to the paper’s constant use and the blinding light that beat down on it every day. A variety of capricious shapes were doodled all over the thing—around the edges, even over some of the numbers, hinting at past reminders that were perhaps later forgotten and never acted upon. Signs of the passage of time and proof of a mind suffering sclerosis.

The year at the top of the calendar had received special attention and was covered with a variety of cryptic signs. Those numbers specifically tasked with representing the ninth day of October were surrounded by further perplexing sigils, which had been scratched in (more in rage than approval) with a pen just a bit lighter than the original black printer’s ink. And alongside several exclamation points, the digits that—as the doodler only now noticed—resonated with magical, numerological power, the power of perfect recurrence: 9-9-9.

Ever since that slow, grim, slippery year had begun, Mario Conde maintained a tormented relationship with the dates at hand. Throughout his life and despite his historically good memory and general obsessiveness, he’d paid little attention to the effect of time’s speed and its implications for his own life and the lives of those around him. Regrettably and all too often, he forgot ages and birthdays, wedding anniversaries, the dates of trivial or major events—from the celebratory to those that evoked grief or commemorated simpler moments—that were or would be important to other people. But the alarming evidence persisted that, among those 365 days squared off by the grid of that cheap calendar, a day lay waiting to pounce that was as yet inconceivable, but threateningly definite and real. The proximity of the day Mario Conde would turn sixty years old caused in him a persistent shock exacerbated by the approach of those notable numbers: 9-9-9. It even sounded indecent (sixty … sixty … something that lets out air and explodes, sssix-ttttty…), and this milestone presented itself as the incontestable confirmation of what his physical (creaky knees, waist, and shoulders; a fatty liver; an ever-lazier penis) and spiritual (dreams, projects, diminished or completely abandoned desires) selves had already been feeling for some time: the obscene arrival of old age …

Was he really an Old Man? In order to confirm it, as he stood before the blurry landscape of the calendar that hung from a pair of nails on his bedroom wall, Conde responded to this question with new ones: Wasn’t his grandfather Rufino an Old Man when, at the age of sixty, he took Conde around the city and surrounding areas to cockfighting rings and taught him the ins and outs of noble combat? Didn’t they start calling Hemingway “Old Man” a few years before his suicide at sixty-one? What about Trotsky? Wasn’t he, at sixty, known as the Old Man when Ramón Mercader split his head in two with a Stalinist and proletarian blow from an ice ax? For starters, Conde knew his limits and understood (owing to well-founded or spurious reasons) that he was a far cry from being his pragmatic grandfather, or Hemingway, or Trotsky, or any other famous old codger. As such, he felt that he had reason enough to avoid so much as aspiring to the category of Old Man, capital letters and all, even as he careened toward that painful number, round and decadent … No, he was, at best, going to become an old fart. The term was more apt in his case—in the category of possible decrepitude as classified with academic zeal by serious geriatric science and the empirical wisdom of an everyman’s street-smart philosophy.

On mornings like this one, suffocatingly hot from the get-go and already inaugurated with his lingering attention to the calendar, those perverse intersections of arithmetic, statistics, memory, and biology invaded him and increased his anguish. Their interconnectedness gave way to a resounding certainty in Conde’s mind. Because even in the best of cases (and the best-case scenario here meant simply staying alive, meant his liver and lungs not letting him down), right in front of him was the numerical evidence of his already having wasted three-quarters (maybe more, no one knows for sure) of the maximum amount of time he would spend on this earth, and the firm conviction that the last part of his allotted span probably wouldn’t turn out any better. Mario Conde knew perfectly well that being old—even being old without being an old fart—is a horrifying condition, due to all it entails, but especially because it carries with it an incontrovertible threat: the statistical and physiological approach of death. Because two plus two is four. Or rather four minus three is one … just one, one-quarter of life left, Mario Conde.

Aches and pains and existential frustrations aside, the presence of that red flag visible on the horizon, near or far, but never entirely gone, had threatened him with greater vigor than ever that morning. Urged by the need to urinate, the need to survive, Conde grappled with the decision to abandon his bed, set aside the desire to burrow into a good book (he still had so many to read, and always less time in which to conquer them!), and resisted even the persistent appeal of throwing himself into his own writing. After expelling his abundant and fetid morning urine, he began the increasingly arduous process of gathering the strength to make his best effort to prevent his own inertia from letting death get ahead of him. In sum: he had to hit the damned streets, the pavement, to make the most of what was left of his life, to avoid the fatal call for as long as possible, and to forget about his pseudophilosophical or literary mental masturbation.

As he drank his coffee and stared hatefully at the damned cigarettes he’d never wanted or been able to give up, he watched his dog’s peaceful sleep: Garbage II, the former living hurricane who, like Conde, had also become slower and more of a homebody as a result of all the pavements he’d pounded. At heart Garbage II was more of a peripatetic gigolo, but lately he’d taken to longer naps and smaller meals, telegraphing his own decrepitude, already visible in the graying of his snout, in the opaqueness of his demanding stare, and in the darkening of his teeth … “What a disaster!” Conde said to himself, caressing the dog’s head and ears, and trying, without much enthusiasm, to plan the coming day. This exercise turned out to be so easy for him that he had enough time left over to continue philosophizing after all, as he absorbed his drags of the day’s first dose of nicotine. Because he knew that, like every other morning, he would hit the pavements in search of old books for sale; then he would eat some ingestible street food, or get a full meal if he let himself swing by the house of Yoyi the Pigeon, his business partner. Later, full of rum, or even sober, he would stop by his friend Skinny Carlos’s house and then end the day by sleeping over at Tamara’s, from whom he’d unjustly absented himself for two days. The panorama ahead of him was nothing new, but it wasn’t unwelcome, either: work, friendship, love, all of it a bit worn, a bit old but still solid and real. The screwed-up part, he admitted to himself, was his state of mind, which was more and more marked by sadness and melancholy, and not just due to the burden of his physical age or the much-feared approach of a terrifying birthday and whatever inevitable consequences would pertain thereto, but because of the certainty of having failed abysmally at life. On the cusp of sixty, what did he have? What was his legacy? Nothing at all. And what awaited him? The same nothing squared—or something worse. These were the only responses within reach of his very simple yet sticky questions. And, to his great dismay, they were likewise the only available responses to so many people, both strangers and friends, of the same age, asking the same questions, inhabiting the same time and space.

Once he was dressed, after giving Garbage II some leftovers and another round of expedient caresses in order to remove a couple of ticks, just as Conde’s mood was improving a bit as he emptied the third and last cup of the infusion that dripped out of his Italian coffeepot, he was startled by the ringing of the telephone. For some time now, calls first thing in the morning or late at night set off all of his alarm bells. Since he was surrounded by so many old people like himself, any incoming call could announce the end—or at least be a harbinger of it.

“Yes?” he asked, expecting the worst.

“Is this Mario Conde’s residence?” A slow, questioning voice. Undefinable, unknown, Conde thought.

He grunted his confirmation, growing more expectant still, before demanding: “Speak.”

“What, you don’t recognize me?”

That sort of question, posed over the telephone, always managed to scramble Conde’s nerves so badly that it sometimes put him into an almost murderous rage. And on this day, of all days, after having enjoyed such a Sartrean morning, the absurdity of it charged at him like a Miura bull. He broke the tension with an explosion of expletives.

“How in the fuck do you expect me to recognize you, shithead?”

“Hey, man, sorry,” the voice came back, now quick and decisive as it hurried on to add, “It’s Bobby, Bobby Roque, from high school … Remember?”

And yes, Conde closed his eyes, nodded, smiled, and shook his head as he detected the distinct fluttering among his neurons of a distant nostalgia, almost vanished, cloaked in the simultaneously grim and pleasant scent of the past—yes, of course he remembered.

* * *

Roberto Roque Rosell, Ro-Ro-Ro … The confluence of his two surnames had been enhanced by his given name, Roberto, so that with all of those Rs and Os, rotund, robust, roaring, virile, refulgent with the appellation that would accompany him his whole life, under the precarious precept that the name makes the man. Perhaps because of this, or—better still—in order to better manifest it, his parents refused to call him Robertico, Robert, or Robby, but rather, ever since he was a boisterous baby in his crib, dubbed him Robertón, trusting that, with that extraordinary face, he would make his way through life honoring this epithet and fulfilling all of his progenitors’ dreams … Fifteen years after his baptism, when Conde happened to meet this Roberto Roque Rosell in one of his classes at La Víbora High School—the same classes where he met Skinny Carlos, Andrés, Rabbit, Candito the Red, Tamara (of course), and even Rafael Morín—the boy was indeed two or three inches taller than the rest of Conde’s friends, but delicate and emaciated, lacking the poundage that would have made him a daunting figure, and already known not as Robertón, much to his parents’ dismay, but simply as Bobby. And not because Bobby was one of the most Anglophilic diminutives possible, so in vogue in those years, and not even due to the fact that this was at the height of Bobby Fischer’s eccentric fame. No, Bobby had to be Bobby because the nickname had the semantic quality that best went with its owner’s most notable characteristics: at fifteen, sixteen years old, the former Robertón of grand ambitions was just kind of dopey and a little too languid—or rather, kind of a fairy, according to the rough linguistic and cultural codes of Conde and his crowd.

Despite never having been what you could call friends, the fact of having been in the same class for a couple of years created a certain closeness between the evanescent Bobby—with whom the others really didn’t have much in common—and Conde, Carlos, Rabbit, and Andrés. Bobby didn’t even like to talk about baseball; in social studies classes, he acted like an ideological Cerberus, barking out slogans; and when it came to music, he was weird enough to prefer Maria Callas to the Beatles and even Creedence. Nevertheless, the kid’s aptitude for matters scientific turned him into a precious jewel his classmates repeatedly clung to when cramming for those difficult subjects on the day before exams. In that context, Conde and his friends had welcomed him as a sort of tutor, in exchange for which they offered Bobby a little protection from the looming, frequent cruelties of their other classmates, generally given to crushing any display of weakness, or the least hint of a predilection for Maria Callas.

Around that time, Conde and his friends discussed the subject often, analyzed it collectively, and came to this conclusion: Bobby was not yet a homosexual, but he would get himself impaled the first chance he got. And it wouldn’t be on an arrow shot by Paris or Pandarus, the Trojan heroes of the Iliad, about whom Bobby spoke as if he’d known them in person. “Doesn’t it seem strange that he likes Achilles so much, huh?” Rabbit used to ask, more a devotee of the Trojans than of the cuckolded Achaeans. Meanwhile, Skinny Carlos, who at the time was even skinnier but just as much of a Good Samaritan as he would remain for the rest of his life, decided to rescue Bobby from the fatal transgression. He assigned himself the task of finding Bobby a female savior among Dulcita’s friends (Dulcita was his girlfriend back then—back then, and later too), but his efforts proved unsuccessful: neither the girls nor Bobby himself seemed too willing to go in for that carnal solution. Soon Bobby and his putative saviors ended up being “just friends,” even confidants—the kind who go around whispering to each other, laughing and holding hands.

When their cohort finished high school and scattered itself through different departments at the university, Conde kept seeing Bobby from time to time, although less frequently. Sometimes they ran into each other at the dining hall, other times they both ended up at one of the recurring required political meetings organized by the Student Federation. Occasionally they rode the same bus. At each encounter, they greeted each other warmly, almost with joy on Bobby’s side, albeit without too much chatter, perhaps because they’d grown apart, each entering their particular milieu, and both felt they had less to say. And then, one afternoon, to Conde’s surprise—a surprise that prompted him to relay the gossip to his friends later that very night—the future detective had run into Bobby at a bar by the university where it was sometimes possible to achieve the Havana miracle of procuring beer. There Bobby was, not only there drinking one of those much-pined-for lagers, but doing so in the presence of a woman whom he introduced as his girlfriend. And though in Conde’s view the woman was no great catch—she was much shorter than Bobby, a little heavyset, with a demeanor that seemed to Conde, perhaps due to his already firmly set opinions, a little crude—Roberto Roque Rosell’s old buddies were happy to hear about Bobby’s conquest. Only Rabbit, who always opted for a dialectical and historical approach, opined that the incident didn’t really signify anything definitive: old Bobby could go both ways, right? Like Achilles, who was light in his loafers!

During Conde’s meeting with the young couple, which proved quite memorable, Bobby had seemed exultant and happy, since he was celebrating his entry to the selective and honorable Young Communist League. As such, he invited his former high school classmate to have a few beers with him, with his red membership ID—¡Estudio, Trabajo, Fusil! (Study, Work, Rifle!)—and his girlfriend (Yumilka? Katiuska? Matrioska?), whom he kissed too frequently and too wetly … And then the guy disappeared, like the Phantom of the Opera … That was probably around 1978, the same year that Conde, at the end of his third year of college, was forced to abandon his studies and, as an alternative to starving to death, surprised himself by accepting a place at the police academy, thus turning (he would always think) the life he could have had upside down. From then on Bobby practically vanished from Conde’s mind, only ever conjured up again during one of those gatherings at which he and his friends might indulge in a little nostalgia and so raise the specter of that obscure character once more. What the hell had become of Bobby? Had he gone North like so many, many other people? No, not Bobby, not Bobby of the Red Guard! Unless he too—was it possible?—had strayed from Party orthodoxy. It wasn’t unheard of.

Which was why, when an androgynous being with dyed ash-blond hair, an earring in his left earlobe, perfectly trimmed eyebrows, and a sparkling smile lighting up a face with a few rogue wrinkles impressed itself upon Conde’s retinas, his brain wasn’t capable of reconciling the vision with his last warehoused image of Bobby: a beer in one hand, eyes overflowing with joy and manly, militant pride, an arm around the shoulders of … Yumilka? Svetlana? Conde knew it had to be him, however—had to be Bobby because after speaking on the phone they’d agreed to meet now (“Perfect, five p.m.”) and here, at Conde’s house (“Yes, the same house as always … older and more fucked-up, like everything else, like all of us.”).

“Ay, but look at you, you’re exactly the same!” his guest said as Conde, wearing a stunned expression, held tight to the doorknob.

“Don’t screw with me, Bobby,” Conde said once he’d recovered from his shock. “If I had this same face forty years ago … then I would have been well and truly fucked. But you, you don’t look anything like you used to…”

“Right? Tell me, what do you think of my look?” Bobby asked, adding in a whisper, “Made in Miami, my friend! The truth is I dye my hair to hide the gray. Old age, vade retro!”

But Conde felt that there hadn’t been a big change in just Bobby’s look, so outlandish and yet so right. His personality had also changed—the two sentences they’d exchanged, and his guest’s effeminate gestures announced it clearly. Conde couldn’t help but think that Bobby now carrying himself in such a way so as to express his true nature (or, anyway, his preferred nature) seemed to have freed him from his tightly wound shyness, since the person he had become displayed an ease that was completely divorced from the lingering image in Conde’s mind of a repressed, not to say compressed, young man: as if Bobby had broken through the chains of selfhood and had actually fashioned himself anew. The benefits of freedom.

“You look good,” Conde admitted, still feeling the effects of his initial shock. He stepped to one side so his visitor could pass. “Come in. So now you live in Miami?”

“No, no,” the other man said. “The clothes and the hair dye are from Miami … The rest, one-hundred-percent Cuban … And speaking of hair dye, you look like you could use some yourself … Check out all that gray! What you need is a little dark chestnut brown!”

Before closing the door, Conde looked up and down the street. He didn’t like the idea too much of people in the neighborhood seeing him let a character like this into his house, although at this age, no one could think any worse of him than they already did. He headed for the kitchen, offered a chair to Bobby, and went over to the stove to light the burner on which the moka pot rested.

“You want some water?” he asked Bobby, who looked his own age for a moment as he wiped away some sweat.

“Is it mineral water? Is it boiled?”

“Mineral? Boiled? The water?” Conde asked.

“Never mind, never mind … I brought my own.” Bobby opened the multicolored bag he had draped across his front to extract a store-bought bottle of water and a manila envelope, which he placed on the table. “You have to be careful—bugs, viruses, all of that garbage polluting the environment. Cholera! Ebola! Chikungunya! Even the names are fucking horrifying. An assault on my brain.”

“You’re right,” Conde said. “Next year, I’ll start boiling my water…”

“Oh, man, you haven’t changed … though maybe you’re a bit more…”

“More what?”

Bobby thought about it before replying.

“More machista…”

“Damn, Bobby, I’m not even that anymore … I’ve got hypertension and must have a death wish since I don’t boil my water…”

Back at the stove, he confirmed that the coffee was almost ready.

“Make mine without sugar!” Bobby requested when Conde took the ancient moka pot off the flames.

“Black coffee now?”

“You have to take care of yourself … We’re getting old…”

“Don’t even start,” Conde said and handed a cup to his health-conscious visitor before putting sugar in his own. As they drank their coffee, he dared to examine his former classmate more closely. He was and was not Bobby. He had gained some weight, not too much, just enough to look more proportional, although his face had softened, in part because of the years, but also, Conde supposed, because it was seemingly animated by a different sort of spirit. And another surprise: besides the earring, the bleached and tinted hair, and the shaped eyebrows, Bobby was sporting a bracelet of blue beads and translucent glass that could only be a proclamation of his initiation into Santería, that tenacious African religion capable of resisting any and all attacks by colonial Christianity, by the bourgeois morality of the Republic, and, indeed, in more recent years (the last fifty?), by the Marxist-atheist offensive. So Bobby, the fervent militant communist, had become a Santero …

“Tell me something about your life,” Conde said and lit a cigarette, surely violating another of his visitor’s rules for healthy living.

“So many things have happened, Conde!” Bobby said and waved a hand delicately. “I don’t even know where to start, man…”

“Wherever the hell you want. Start with the earring and the hair, maybe…”

Bobby smiled sadly. “Ash blond … That’s a long, loooong story, but I’ll try to give you the short version. I got married, okay? Had two sons, who are men already, real men now, by the way…”

“How nice!” Conde was bowled over. “Did you marry that girl from the university? Yumilka?”

“Katiuska!” Bobby exclaimed and immediately added, “That bitch Katiuska! How do you even remember her?”

“So what did Katiuska ever do to you? She got uglier, or something? She cheated on you?” Conde asked, to avoid responding.

Bobby looked at him with a helplessness in his eyes that, for the first time, allowed the former cop to find in the sight of the man before him the ghost of the vulnerable boy he had met so many years before: an air of distress with a hint of sadness, a lot of frailty, and far too much fear.

“No, she didn’t cheat on me. And I didn’t marry her anyway. Katiuska just fucked up my life … or saved it, I don’t know … But that’s not the story I wanted to tell you. Look, I’ll give you the quick lowdown, okay? After university, I married Estela, Estelita, the mother of my two sons. And everything was smooth sailing until, through some business dealings, I met Israel and … I cracked! I fell in love like a dog, no, like a goddamn bitch!”

And Conde thought, Maybe Bobby’s whole amazing story is just one long, liberating escape from the closet?

Bobby drained his cup of coffee and pointed at Conde’s pack of cigarettes.

Conde grinned. “Smoking is hazardous for your health, or didn’t you hear?”

“It sure is,” Bobby said, “but I want one real bad!”

He lit the cigarette Conde gave him and exhaled smoke with evident pleasure.

“Listen, Conde … did you ever end up writing anything?”

“Writing? Sure. I’ve done a few things,” he said, which was true—but without knowing why, he felt the need to dress up his response, as if he needed to excuse himself before the world. “I’m thinking of putting a book together … but let’s leave that aside for now … Go on with your story.”

“Well, so … I got separated from Estelita, I moved in with Israel, and we were together for about ten years, until he left for Miami because he couldn’t stand the heat anymore…”

“They say in Miami it’s also hot as hell, no?”

“Oh, come on, man, that thing about the heat is just an excuse … Israel couldn’t take it anymore … You know, the situation, the thing…” And he made a gesture as if to include everything around them.

“Ah, yes, the thing,” Conde said. “And?”

“And nothing. The usual … I’ve had a lot of partners, until about two years ago, I met Raydel and … I fell in love like a goddamn rabid bitch again, and an old one too, this time!”

“It’s good to be in love,” Conde said. He too was prone to falling into that state of grace and vulnerability. Although in his case, it had only involved women, and, for many years now, the same woman.

“But it’s dangerous, very dangerous … That’s why I’m here.”

“Because you’re in love?”

“Because of the consequences…”

“You lost me.”

Bobby crushed his half-smoked cigarette in the ashtray after taking one last, gluttonous drag, just as Conde slid out another for himself and lit it.

“Let’s see, let’s see, how do I explain this to you…” Bobby ran his hand through his faded hair and blinked several times. “It’s just that this is terrible, man! I met Raydel at my Padrino’s house,” he began and touched the bracelet of brilliantly colored beads around his wrist before leaning to one side and placing his fingertips on the floor and then lifting them back to his lips. “It’s been eighteen years already since I was initiated into Santería … receiving Yemayá at my ceremony…”

“Wait, wait. The way I remember it, you were a dialectical materialist, no?” Conde said after taking in Bobby’s ritual in inquisitive silence while fighting to repress thoughts of roughing up (just a bit!) this former slogan-spouting Marxist zealot who’d ended up a devotee of something so primitive, so Afro-Cuban—and which, of course, was no less an opiate than any other religion, as Karl himself would put it.

“Conde, look, that was just a mask I had to wear … like almost everyone does at one time or another, right? My entire life, I had to hide that I was gay, hide that I believed in God and in the most Holy Virgin Mother … So I spent my first forty years pretending, repressing, torturing myself, so that my parents, so that all of you, my friends, so that everyone in our macho-socialist homeland would believe that I was what I should have been and wouldn’t take everything away from me. I had to be an exemplary young man, virile and politically engaged, an atheist, obedient … You can’t imagine what my life was like, not a chance…”

Conde didn’t dare comment. He knew all about the masks and the hiding and the pressures that so many people had needed to withstand to live in a society so focused on regimenting ethical, political, and social behaviors, and in repressing—rigorously, even wrathfully—any display of difference. And Bobby must have been the perfect victim.

“Anyway, as I was saying … I met Raydel at my Padrino’s house. Raydel had just arrived from Palma Soriano, out there near Santiago de Cuba, and he was in the business of selling animals to Santeros … I wish you could’ve seen him: olive-skinned with these big eyes, lush lashes, a mouth like—”

“Don’t,” Conde cut him off. “That’s enough. I get it, you fell in love. And?”

“I gave him a good bath to get rid of his goat stink and then I got together with that precious thing. I took him to my house. We lived together for two years, it was like a dream … And well, then Israel invited me to visit Miami and those American imperialist gentlemen were crazy enough to give me a visa. I went over there for two months, to see Israel and to try to arrange some things for my business while I was at it…”

“You have a business?” Conde arched an eyebrow: his former classmate was simply unfathomable. Now he was a capitalist, too?

“Sure, I deal in objets d’art, jewelry, expensive things like that…”

“And when you got home, you found out that Raydel had disappeared along with everything he could carry…”

Bobby’s amazement was tangible. He blinked several times, as if Conde must have read his mind.

“Christ, Bobby,” Conde came to his rescue, “I may not be a Santero, but try and remember that I was a cop for ten years … If you came looking for me, of all people, I had to figure it’s because something fucked-up happened, right…?”

Bobby nodded, his face settling into an expression of great sadness.

“Yeah, he took it all, Conde, every damn bit of it … Jewelry, the TV, even the light bulbs and pots and pans!”

“Shit.”

“Luckily, before leaving, I sold lots of things to get dollars to take to Miami to invest in some businesses I set up over there … But, even still, Raydel brought a truck around and just cleaned me out … He took everything. The mattress! The kettle for boiling water to kill bugs!”

“Did you go to the cops?”

Bobby shook his head no as if the very idea struck h

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...