- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

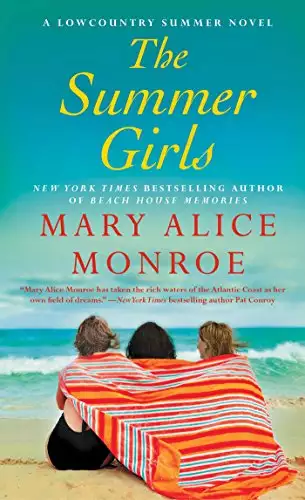

Three sisters reunite on Sullivan’s Island off the coast of South Carolina after years of separation in this heartwarming first novel in a new trilogy from a beloved author.

Eighty-year-old Marietta Muir is a dowager of Charleston society who has retired to her historic summer home on Sullivan’s Island. At the onset of summer, Marietta, “Mamaw,” seeks to gather her three granddaughters—Carson, Eudora, and Harper—with the intent to reunite them after years apart. Monroe explores the depths and complexities of sisterhood, friendship, and the power of forgiveness. The Summer Girls is a perfect beach read and anyone who “enjoys such fine Southern voices as Pat Conroy will add the talented Monroe to their list of favorites” (Booklist).

Release date: June 25, 2013

Publisher: Gallery Books

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Summer Girls

Mary Alice Monroe

CHAPTER ONE

LOS ANGELES

Carson was sorting through the usual boring bills and circulars in the mail when her fingers paused at the thick ecru envelope with Miss Carson Muir written in a familiar blue script. She clutched the envelope tight and her heart pumped fast as she scurried up the hot cement steps back to her apartment. The air-conditioning was broken, so only scarce puffs of breeze that carried noise and dirt from the traffic wafted through the open windows. It was a tiny apartment in a two-story stucco building near L.A., but it was close to the ocean and the rent was affordable, so Carson had stayed for three years, longer than she’d ever lived in any other apartment.

Carson carelessly tossed the other mail onto the glass cocktail table, stretched her long limbs out on the nubby brown sofa, then slid her finger along the envelope’s seal. Waves of anticipation crested in her bloodstream as she slowly pulled out the navy-trimmed, creamy stationery card. Immediately she caught a whiff of perfume—soft sweet spices and orange flowers—and, closing her eyes, she saw the Atlantic Ocean, not the Pacific, and the white wooden house on pilings surrounded by palms and ancient oaks. A smile played on her lips. It was so like her grandmother to spray her letters with scent. So old world—so Southern.

Carson nestled deeper in the cushions and relished each word of the letter. When finished, she looked up and stared in a daze at the motes of dust floating in a shaft of sunlight. The letter was an invitation . . . was it possible?

In that moment, Carson could have leaped to her feet and twirled on her toes, sending her long braid flying like that of the little girl in her memories. Mamaw was inviting her to Sullivan’s Island. A summer at Sea Breeze. Three whole rent-free months by the sea!

Mamaw always had the best timing, she thought, picturing the tall, elegant woman with hair the color of sand and a smile as sultry as a lowcountry sunset. It had been a horrid winter of endings. The television series Carson had been working on had been canceled without warning after a three-year run. Her cash flow was almost gone and she was just trying to figure out how she could make next month’s rent. For months she’d been bobbing around town looking for work like a piece of driftwood in rough waters.

Carson looked again at the letter in her hand. “Thank you, Mamaw,” she said aloud, feeling it deeply. For the first time in months Carson felt a surge of hope. She paced a circle, her fingers flexing, then strode to the fridge and pulled out a bottle of wine and poured herself a mugful. Next she crossed the room to her small wood desk, pushed the pile of clothing off the chair, then sat down and opened her laptop.

To her mind, when you were drowning and a rope was thrown your way, you didn’t waste time thinking about what to do. You just grabbed it, then kicked and swam like the devil to safety. She had a lot to do and not much time if she was going to be out of the apartment by the month’s end.

Carson picked up the invitation again, kissed it, then put her hands on the keys and began typing. She would accept Mamaw’s invitation. She was going back to the lowcountry—to Mamaw. Back to the only place in the world she’d ever thought of as home.

SUMMERVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA

Dora stood at the kitchen stove stirring a red sauce. It was 5:35 P.M. and the rambling Victorian house felt empty and desolate. She used to be able to set a clock by her husband’s schedule. Even now, six months after Calhoun had left, Dora expected him to walk through the door carrying the mail. She’d lift her cheek toward the man who had been her husband for fourteen years to receive his perfunctory kiss.

Dora’s attention was caught by the sound of pounding footfalls on the stairs. A moment later, her son burst into the room.

“I made it to the next level,” he announced. He wasn’t smiling, but his eyes sparkled with triumph.

Dora smiled into his face. Her nine-year-old son made up her world. A big task for such a small boy. Nate was slight and pale, with furtive eyes that always made her wonder why her little boy was afraid. Of what? she’d asked his child psychiatrist, who had smiled kindly. “Nate isn’t so much afraid as he is guarded,” he’d answered reassuringly. “You shouldn’t take it personally, Mrs. Tupper.”

Nate had never been a cuddly baby, but she worried when his smiling stopped after a year. By two, he didn’t establish eye contact or turn his head when called. By three, he no longer came to her for comfort when he was hurt, nor did he notice or care if she cried or got angry. Except if she yelled. Then Nate covered his ears and commenced rocking in a panic.

Her every instinct had screamed that something was wrong with her baby and she began furtively reading books on child development. How many times had she turned to Cal with her worries that Nate’s speech development was behind the norm and that his movements were clumsy? And how many times had Cal turned on her, adamant that the boy was fine and she was making it all up in her head? She’d been like a turtle tucking her head in, afraid to go against him. Already the subject of Nate’s development was driving a wedge between them. When Nate turned four, however, and began flapping his hands and making odd noises, she made her first, long-overdue appointment with a child psychiatrist. It was then that the doctor revealed what Dora had long feared: her son had high-functioning autism.

Cal received the diagnosis as a psychological death sentence. But Dora was surprised to feel relieved. Having an official diagnosis was better than making up excuses and coping with her suspicions. At least now she could actively help her son.

And she did. Dora threw herself into the world of autism spectrum disorders. There was no point in gnashing her teeth wishing that she’d followed up on her own instincts sooner, knowing now that early diagnosis and treatment could have meant important strides in Nate’s development. Instead, she focused her energy on a support group and worked tirelessly to develop an intensive in-home therapy program. It wasn’t long before her entire life revolved around Nate and his needs. All her plans for restoring her house fell by the wayside, as did hair appointments, lunches with friends, her size-eight clothes.

And her marriage.

Dora had been devastated when Cal announced seemingly out of the blue one Saturday afternoon in October that he couldn’t handle living with her and Nate any longer. He assured her she would be taken care of, packed a bag, and walked out of the house. And that was that.

Dora quickly turned off the stove and wiped her hands on her apron. She put on a bright smile to greet her son, fighting her instinct to lean over and kiss him as he entered the room. Nate didn’t like being touched. She reached over to the counter to retrieve the navy-trimmed invitation that had arrived in the morning’s mail.

“I’ve got a surprise for you,” she told him with a lilt in her voice, feeling that the time was right to share Mamaw’s summer plans.

Nate tilted his head, mildly curious but uncertain. “What?”

She opened the envelope and pulled out the card, catching the scent of her grandmother’s perfume. Smiling with anticipation, Dora quickly read the letter aloud. When Nate didn’t respond, she said, “It’s an invitation. Mamaw is having a party for her eightieth birthday.”

He immediately shrank inward. “Do I have to go?” he asked, his brow furrowed with worry.

Dora understood that Nate didn’t like to attend social gatherings, not even for people he loved, like his great-grandmother. Dora bent closer and smiled. “It’s just to Mamaw’s house. You love going to Sea Breeze.”

Nate turned his head to look out the window, avoiding her eyes as he spoke. “I don’t like parties.”

Nor was he ever invited to any, she thought sadly. “It’s not really a party,” Dora hastened to explain, careful to keep her voice upbeat but calm. She didn’t want Nate to set his mind against it. “It’s only family coming—you and me and your two aunts. We’re invited to go to Sea Breeze for the weekend.” A short laugh of incredulousness burst from her throat. “For the summer, actually.”

Nate screwed up his face. “For the summer?”

“Nate, we always go to Sea Breeze to see Mamaw in July, remember? We’re just going a little earlier this year because it is Mamaw’s birthday. She will be eighty years old. It’s a very special birthday for her.” She hoped she’d explained it clearly enough for him to work it out. Nate was extremely uncomfortable with change. He liked everything in his life to be in order. Especially now that his daddy had left.

The past six months had been rocky for both of them. Though there had never been much interaction between Nate and his father, Nate had been extremely agitated for weeks after Cal moved out. He’d wanted to know if his father was ill and had gone to the hospital. Or was he traveling on business like some of his classmates’ fathers? When Dora made it clear that his father was not ever returning to the house to live with them, Nate had narrowed his eyes and asked her if Cal was, in fact, dead. Dora had looked at Nate’s taciturn face, and it was unsettling to realize that he wasn’t upset at the possibility his father might be dead. He merely needed to know for certain whether Calhoun Tupper was alive or dead so that all was in order in his life. She had to admit that it made the prospect of a divorce less painful.

“If I go to Mamaw’s house I will need to take my tetra,” Nate told her at length. “The fish will die if I leave it alone in the house.”

Dora slowly released her breath at the concession. “Yes, that’s a very good idea,” she told him cheerfully. Then, because she didn’t want him to dwell and because it had been a good day for Nate so far, she moved on to a topic that he wouldn’t find threatening. “Now, suppose you tell me about the new level of your game. What is your next challenge?”

Nate considered this question, then tilted his head and began to explain in tedious detail the challenges he faced in the game and how he planned to meet them.

Dora returned to the stove, careful to mutter, “Uh-huh,” from time to time as Nate prattled on. Her sauce had gone cold and all the giddiness that she’d experienced when reading the invitation fizzled in her chest, leaving her feeling flat. Mamaw had been clear that this was to be a girls-only weekend. Oh, Dora would have loved a weekend away from the countless monotonous chores for a few days of wine and laughter, of catching up with her sisters, of being a Summer Girl again. Only a few days . . . Was that too much to ask?

Apparently, it was. She’d called Cal soon after the invitation had arrived.

“What?” Cal’s voice rang in the receiver. “You want me to babysit? All weekend?”

Dora could feel her muscles tighten. “It will be fun. You never see Nate anymore.”

“No, it won’t be fun. You know how Nate gets when you leave. He won’t accept me as your substitute. He never does.”

She could hear in his voice that he was closing doors. “For pity’s sake, Cal. You’re his father. You have to figure it out!”

“Be reasonable, Dora. We both know Nate will never tolerate me or a babysitter. He gets very upset when you leave.”

Tears began to well in her eyes. “But I can’t bring him. It’s a girls-only weekend.” Dora lifted the invitation. “It says, ‘This invitation does not include husbands, beaus, or mothers.’ ”

Cal snorted. “Typical of your grandmother.”

“Cal, please . . .”

“I don’t see what the problem is,” he argued, exasperation creeping into his voice. “You always bring Nate along with you when you go to Sea Breeze. He knows the house, Mamaw . . .”

“But she said—”

“Frankly, I don’t care what she said,” Cal said, cutting her off. There was a pause, then he said with a coolness of tone she recognized as finality, “If you want to go to Mamaw’s, you’ll have to bring Nate. That’s all there is to it. Now good-bye.”

It had always been this way with Cal. He never sought to see all of Nate’s positive qualities—his humor, intelligence, diligence. Rather, Cal had resented the time she spent with their son and complained that their lives revolved around Nate and Nate alone. So, like an intractable child himself, Cal had left them both.

Dora’s shoulders slumped as she affixed Mamaw’s invitation to the refrigerator door with a magnet beside the grocery list and a school photo of her son. In it, Nate was scowling and his large eyes stared at the camera warily. Dora sighed, kissed the photo, and returned to cooking their dinner.

While she chopped onions, tears filled her eyes.

NEW YORK CITY

Harper Muir-James picked at the piece of toast like a bird. If she nibbled small pieces and chewed each one thoroughly, then sipped water between bites, she found she ate less. As she chewed, Harper’s mind was working through the onslaught of emotions that had been roiling since she opened the invitation in the morning’s mail. Harper held the invitation between her fingers and looked at the familiar blue-inked script.

“Mamaw,” she whispered, the name feeling foreign on her lips. It had been so long since she’d uttered the name aloud.

She propped the thick card up against the crystal vase of flowers on the marble breakfast table. Her mother insisted that all the rooms of their prewar condo overlooking Central Park always have fresh flowers. Georgiana had grown up at her family estate in England, where this had been de rigueur. Harper’s gaze lazily shifted from the invitation to the park outside her window. Spring had come to Central Park, changing the stark browns and grays of winter to an explosion of spring green. In her mind’s eye, however, the scene shifted to the greening cordgrass in the wetlands of the lowcountry, the snaking creeks dotted with docks, and the large, waxy white magnolia blooms against glossy green leaves.

Her feelings for her Southern grandmother were like the waterway that raced behind Sea Breeze—deep, and swelling with happy memories. In the invitation Mamaw had referred to her “Summer Girls.” That was a term Harper hadn’t heard—had not even thought about—in over a decade. She hadn’t been but twelve years old when she spent her last summer at Sea Breeze. How many times had she seen Mamaw in all those years? It surprised Harper to realize it had been only three times.

There had been so many invitations sent to her in those intervening years. So many regrets returned. Harper felt a twinge of shame as she pondered how she could have let so many years pass without paying Mamaw a visit.

“Harper? Where are you?” a voice called from the hall.

Harper coughed on a crumb of dry toast.

“Ah, there you are,” her mother said, walking into the kitchen.

Georgiana James never merely entered a room; she arrived. There was a rustle of fabric and an aura of sparks of energy radiating around her. Not to mention her perfume, which was like the blare of trumpets entering the room before her. As the executive editor of a major publishing house, Georgiana was always rushing—to meet a deadline, to meet someone for lunch or dinner, or to another in a string of endless meetings. When Georgiana wasn’t rushing off somewhere she was ensconced behind closed doors reading. In any case, Harper had seen little of her mother growing up. Now, at twenty-eight years of age, she worked as her mother’s private assistant. Though they lived together, Harper knew that she needed to make an appointment with her mother for a chat.

“I didn’t expect you to still be here,” Georgiana said, pecking her cheek.

“I was just leaving,” Harper replied, catching the hint of censure in the tone. Georgiana’s pale blue tweed jacket and navy pencil skirt fitted her petite frame impeccably. Harper glanced down at her own sleek black pencil skirt and gray silk blouse, checking for any loose thread or missing button that her mother’s hawk eye would pick up. Then, in what she hoped was a nonchalant move, she casually reached for the invitation that she’d foolishly propped up against the glass vase of flowers.

Too late.

“What’s that?” Georgiana asked, swooping down to grasp it. “An invitation?”

Harper’s stomach clenched and, not replying, she glanced up at her mother’s face. It was a beautiful face, in the way that a marble statue was beautiful. Her skin was as pale as alabaster, her cheekbones prominent, and her pale red hair was worn in a blunt cut that accentuated her pointed chin. There was never a strand out of place. Harper knew that at work they called her mother “the ice queen.” Rather than be offended, Harper thought the name fit. She watched her mother’s face as she read the invitation, saw her lips slowly tighten and her blue eyes turn frosty.

Georgiana’s gaze snapped up from the card to lock with Harper’s. “When did you get this?”

Harper was as petite as her mother and she had her pale complexion. But unlike her mother’s, Harper’s reserve was not cold but more akin to the stillness of prey.

Harper cleared her throat. Her voice came out soft and shaky. “Today. It came in the morning mail.”

Georgiana’s eyes flashed and she tapped the card against her palm with a snort of derision. “So the Southern belle is turning eighty.”

“Don’t call her that.”

“Why not?” Georgiana asked with a light laugh. “It’s the truth, isn’t it?”

“It isn’t nice.”

“Defensive, are we?” Georgiana said with a teasing lilt.

“Mamaw writes that she’s moving,” Harper said, changing the subject.

“She’s not fooling anyone. She’s tossing out that comment like bait to draw you girls in for some furniture or silver or whatever she has in that claptrap beach house.” Georgiana sniffed. “As if you’d be interested in anything she might call an antique.”

Harper frowned, annoyed by her mother’s snobbishness. Her family in England had antiques going back several hundred years. That didn’t diminish the lovely American antiques in Mamaw’s house, she thought. Not that Harper wanted anything. In truth, she was already inheriting more furniture and silver than she knew what to do with.

“That’s not why she’s invited us,” Harper argued. “Mamaw wants us all to come together again at Sea Breeze, one last time. Me, Carson, Dora . . .” She lifted her slight shoulders. “We had some good times there. I think it might be nice.”

Georgiana handed the invitation back to Harper. She held it between two red-tipped fingers as though it were foul. “Well, you can’t go, of course. Mum and a few guests are arriving from England the first of June. She’s expecting to see you in the Hamptons.”

“Mamaw’s party is on the twenty-sixth of May and Granny James won’t arrive until the following week. It shouldn’t be a problem. I can go to the party and be in the Hamptons in plenty of time.” Harper hurried to add, “I mean, it is Mamaw’s eightieth birthday after all. And I haven’t seen her in years.”

Harper saw her mother straighten her shoulders, her nostrils flaring as she tilted her chin, all signs Harper recognized as pique.

“Well,” Georgiana said, “if you want to waste your time, go ahead. I’m sure I can’t stop you.”

Harper pushed away her plate, her stomach clenching at the warning implicit in the statement: If you go I will not be pleased. Harper looked down at the navy-trimmed invitation and rubbed her thumb against the thick vellum, feeling its softness. She thought again of the summers at Sea Breeze, of Mamaw’s amused, tolerant smile at the antics of the Summer Girls.

Harper looked back at her mother and smiled cheerily. “All right then. I rather think I will go.”

Four weeks later Carson’s battered Volvo wagon limped over the Ben Sawyer Bridge toward Sullivan’s Island like an old horse heading to the barn. Carson turned off the music and the earth fell into a hush. The sky over the wetlands was a panorama of burnt sienna, tarnished gold, and moody shades of blue. The few wispy clouds would not mar the great fireball’s descent into the watery horizon.

She crossed the bridge and her wheels were on Sullivan’s Island. She was almost there. The reality of her decision made her fingers tap along the wheel in agitation. She was about to show up on Mamaw’s doorstep to stay for the entire summer. She sure hoped Mamaw had been sincere in that offer.

In short order Carson had given up her apartment, packed everything she could in her Volvo, and put the rest into storage. Staying with Mamaw provided Carson with a sanctuary while she hunted for a job and saved a few dollars. It had been an exhausting three-day journey from the West Coast to the East Coast, but she’d arrived at last, bleary-eyed and stiff-shouldered. Yet once she left the mainland, the scented island breezes gave her a second wind.

The road came to an intersection at Middle Street. Carson smiled at the sight of people sitting outdoors at restaurants, laughing and drinking as their dogs slept under the tables. It was early May. In a few weeks the summer season would begin and the restaurants would be overflowing with tourists.

Carson rolled down the window and let the ocean breeze waft in, balmy and sweet smelling. She was getting close now. She turned off Middle Street onto a narrow road heading away from the ocean to the back of the island. She passed Stella Maris Catholic Church, its proud steeple piercing a periwinkle sky.

The wheels crunched to a stop on the gravel and Carson’s hand clenched around the can of Red Bull she’d been nursing.

“Sea Breeze,” she murmured.

The historic house sat amid live oaks, palmettos, and scrub trees overlooking the beginning of where Cove Inlet separated Charleston Harbor from the Intracoastal Waterway. At first peek, Sea Breeze seemed a modest wood-framed house with a sweeping porch and a long flight of graceful stairs. Mamaw had had the original house raised onto pilings to protect it from tidal surges during storms. It was at that same time that Mamaw had added to the house, restored the guest cottage, and repaired the garage. This hodgepodge collection of wood-frame buildings might not have had the showy grandeur of the newer houses on Sullivan’s, Carson thought, but none of those houses could compare with Sea Breeze’s subtle, authentic charm.

Carson turned off the lights, closed her bleary eyes, and breathed out in relief. She’d made it. She’d journeyed twenty-five hundred miles and could still feel the rolling of them in her body. Sitting in the quiet car, she opened her eyes and stared out the windshield at Sea Breeze.

“Home,” she breathed, tasting the word on her lips. Such a strong word, laden with meaning and emotion, she thought, feeling suddenly unsure. Did birth alone give her the right to make that claim on this place? She was only a granddaughter, and not a very attentive one at that. Though, unlike the other girls, for her, Mamaw was more than a grandmother. She was the only mother Carson had ever known. Carson had been only four years old when her mother died and her father left her to stay with Mamaw while he went off to lick his wounds and find himself again. He came back for her four years later to move to California, but Carson had returned every summer after that until she was seventeen. Her love for Mamaw had always been like that porch light, the one true shining light in her heart when the world proved dark and scary.

Now, seeing Sea Breeze’s golden glow in the darkening sky, she felt ashamed. She didn’t deserve a warm welcome. She’d visited a handful of times in the past eighteen years—two funerals, a wedding, and a couple of holidays. She’d made too many excuses. Her cheeks flamed as she realized how selfish it was of her to assume that Mamaw would always be here, waiting for her. She swallowed hard, facing the truth that she likely wouldn’t even have come now except that she was broke and had nowhere else to go.

Her breath hitched as the front door opened and a woman stepped out onto the porch. She stood in the golden light, straight-backed and regal. In the glow, her wispy white hair created a halo around her head.

Carson’s eyes filled as she stepped from the car.

Mamaw lifted her arm in a wave.

Carson felt the tug of connection as she dragged her suitcase in the gravel toward the porch. As she drew near, Mamaw’s blue eyes shone bright and welcoming. Carson let go of her baggage and ran up the stairs into Mamaw’s open arms. She pressed her cheek against Mamaw’s, was enveloped in her scent, and all at once she was four years old again, motherless and afraid, her arms tight around Mamaw’s waist.

“Well now,” Mamaw said against her cheek. “You’re home at last. What took you so long?”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...