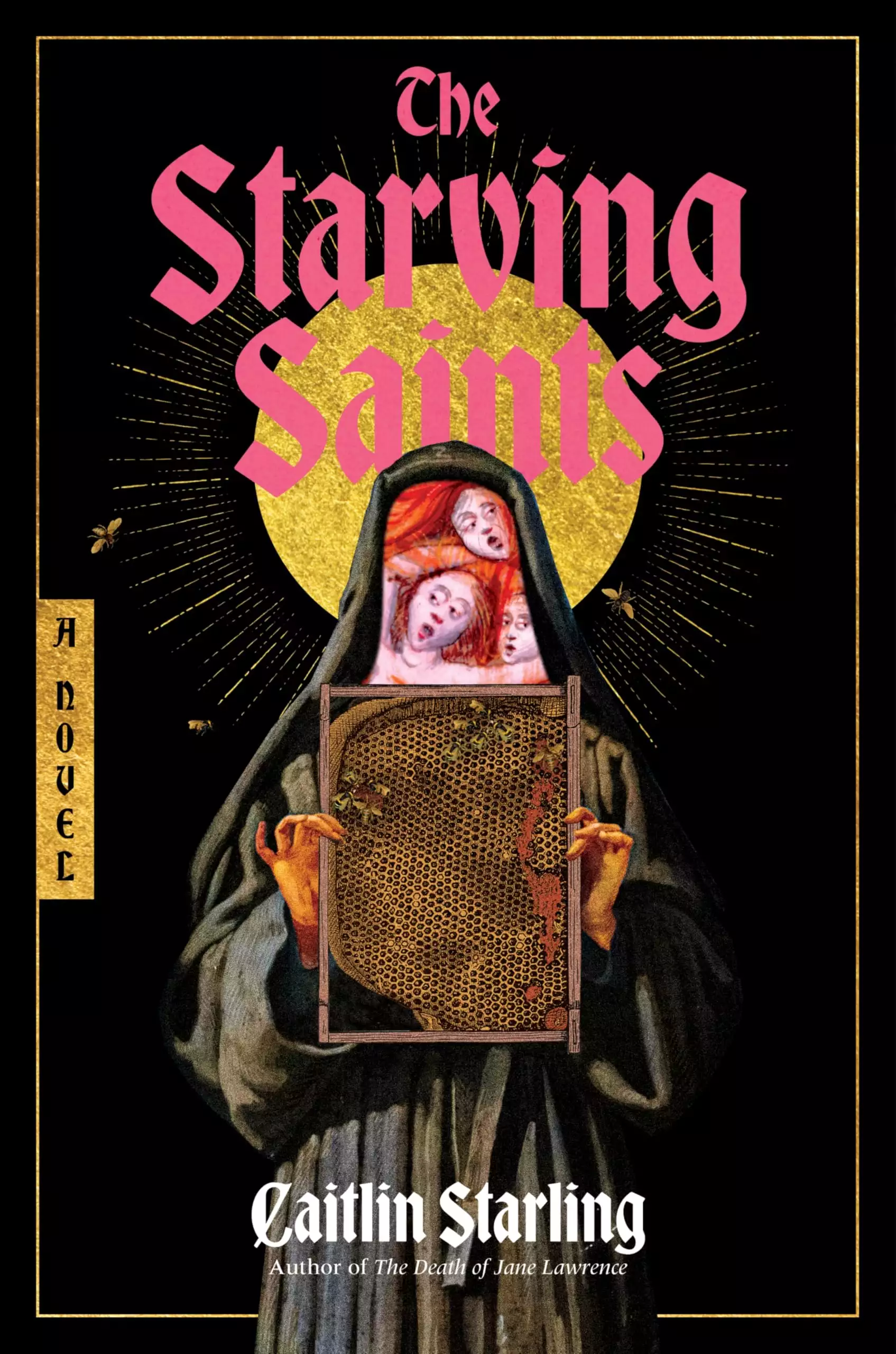

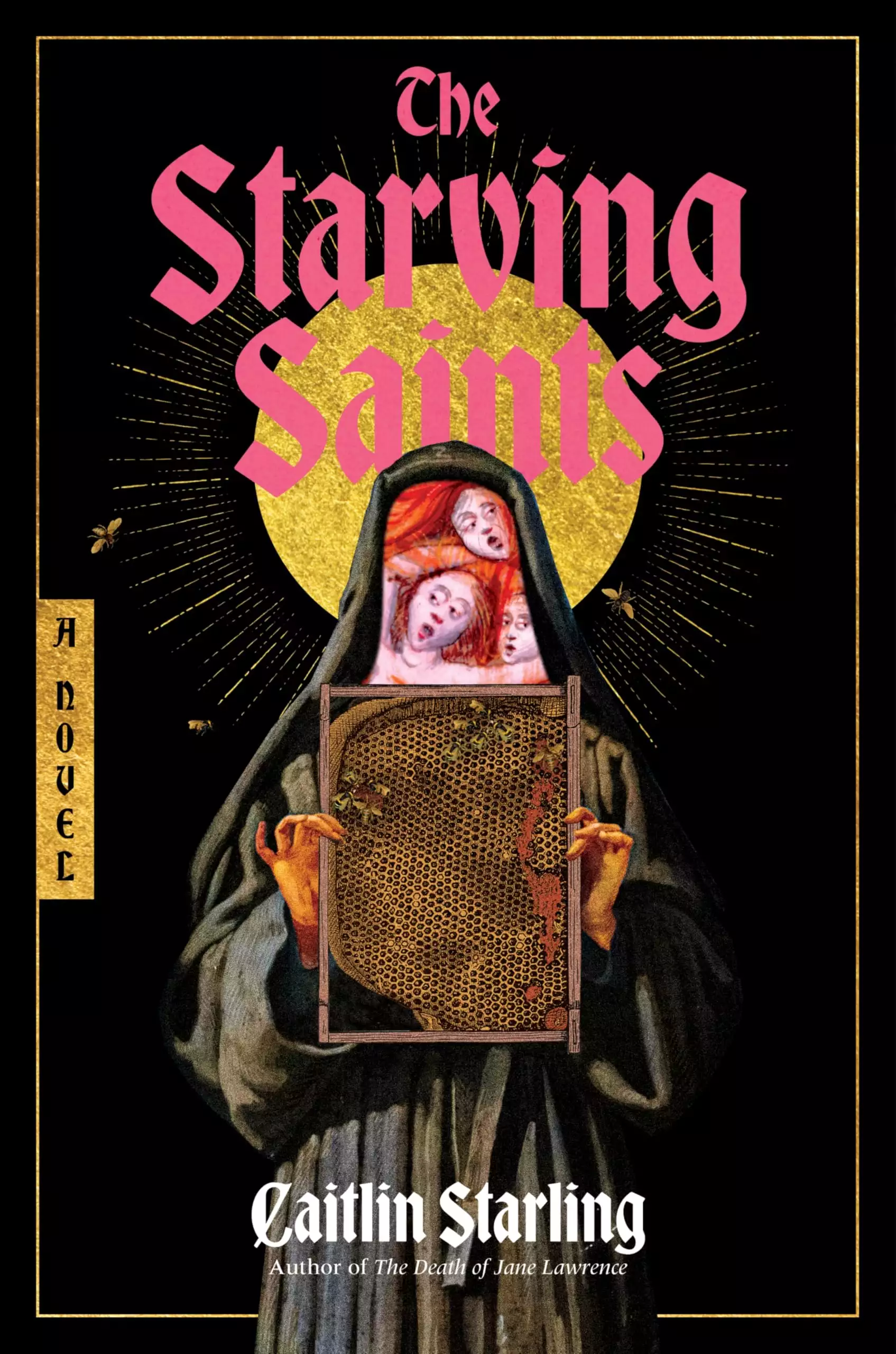

The Starving Saints

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

From the nationally bestselling author of The Luminous Dead and The Death of Jane Lawrence, a transfixing, intensely atmospheric fever dream of medieval horror.

Aymar Castle has been under siege for six months. Food is running low and there has been no sign of rescue. But just as the survivors consider deliberately thinning their number, the castle stores are replenished. The sick are healed. And the divine figures of the Constant Lady and her Saints have arrived, despite the barricaded gates, offering succor in return for adoration.

Soon, the entire castle is under the sway of their saviors, partaking in intoxicating feasts of terrible origin. The war hero Ser Voyne gives her allegiance to the Constant Lady. Phosyne, a disorganized, paranoid nun-turned-sorceress, races to unravel the mystery of these new visitors and exonerate her experiments as their source. And in the bowels of the castle, a serving girl, Treila, is torn between her thirst for a secret vengeance against Voyne and the desperate need to escape from the horrors that are unfolding within Aymar’s walls.

As the castle descends into bacchanalian madness—forgetting the massed army beyond its walls in favor of hedonistic ecstasy—these three women are the only ones to still see their situation for what it is. But they are not immune from the temptations of the castle’s new masters… or each other; and their shifting alliances and entangled pasts bring violence to the surface. To save the castle, and themselves, will take a reimagining of who they are, and a reorganization of the very world itself.

Release date: May 20, 2025

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Starving Saints

Caitlin Starling

In fifteen days, there will be no food in Aymar Castle.

She has done the arithmetic forward and back. They have been down to strangled rations for weeks now, and there have been mistakes. Thefts. Impulsive, desperate gorgings. Even if every soul in Aymar Castle keeps to their allotted portion—and Phosyne does not think that is likely—every soul in Aymar Castle will run out of food in fifteen days.

And though Phosyne is one of the few outside the Priory who can work sums, everybody else is bound to realize this soon.

They are packed in one atop the other; a castle meant to hold at most three hundred for any length of time now shelters three times that. Every nook and cranny is full to bursting of terrified farmers and a pitiful handful of overwrought knights. They’ve been living in this unbearable press for almost six months now. It’s a testament to Ser Leodegardis’s leadership that they’ve lasted this long, that the siege outside their walls has not broken them, that plague has not crashed down heavy on their heads. But time is inexorable, as is the human stomach.

Relief has not come. They do not know if it will.

Fifteen days.

Phosyne counts out her own stores, meant to last her another three. She doesn’t eat much, so they might last her a little longer, except she has two little mouths to feed that the quartermaster doesn’t know about. Her companions slink along the walls and ceiling, all long, sleek bodies and dark scales, looking for a crevice to slip through. Ornuo stole a chicken a month and a half ago, but Phosyne has since stopped up her few windows. No chance of that happening again. (She does not know the depths of their hungers and desperations, nor even their real nature. She worries that they will begin to nibble on her toes as she sleeps.)

She tosses out a bit of ox hide she can’t bring herself to stomach yet, and Pneio snaps it from the air, then retreats beneath her desk to gnaw at it. His brother darts after him. They tussle.

For herself, she takes nothing, instead locking the strips of tough dried meat and gristle back inside the heavy box she’s reassigned for the purpose. Later, she’ll eat later, after she’s made some progress. Progress is the only reason she’s been afforded the rations she has been, the only reason she is allowed to live alone despite the pack of bodies throughout the rest of the keep. Progress earns her the candles she burns down to nubs in the close darkness of her stoppered tower.

Progress has not been forthcoming, as of late.

Her stomach cramps in irritation as she mounts the steps up to the loft above her main floor. When she moved in, this room was one of the most unpleasant in the castle: damp, fetid, filled with moss and fungus thanks to the cooling influence of the rain cistern below the floor. Now it is dry and warm, yet another impossibility she tries to keep hidden. It’s the sort of thing the Priory would take issue with. Eventually, somebody will notice, word will spread. Nothing lasts forever without changing.

Or breaking.

She settles on the sill of the one window that still lets in a shaft of light, through a dull pane of glass she’s secured into a mass of wood and mud and pitch. Outside, it’s early evening; the sun is setting atop the keep walls, and beyond them, she can just make out the line of contravallation, the wall their enemy has built to keep them in, should they ever risk leaving the castle’s safety. That wall sits between them and fields, fields that have either been torched or taken over by the thousands of soldiers and laborers that surround them. In six months, they have built a thriving town. They squat on the land and

take its bounty for their own.

Her last experiment was too bold, she can see that now. Transporting food that she cannot see, through so much stone and across so many bodies? Impossible. But she is getting desperate, just like the rest.

Her other attempts were more reasonable, yet no less doomed. She has failed to speed the germination of seeds for the castle gardens. She has caused only blight when she has attempted to divide and propagate summer squash and sprigs of herbs. Her only success so far has been a process by which fouled water can be made clean again; invaluable, necessary, but not enough.

Phosyne’s head pounds, and she curls up into a tight little ball. Her fingers itch. Her whole body itches, really, with the lice and fleas that have grown rampant in the last few months, but her fingers itch for action. Desperate action. If she opens the little glass pane, and lets Ornuo and Pneio out—

They will not go out to foreign lands and bring her back a feast. They’ll only stalk starving babes in the crib. Foul creatures, unknown to any bestiary she has consulted, affectionate but untrustworthy.

Something bangs against her door.

It happens again, and she must concede it’s not an accidental collision. She is beginning to panic that they are here to take her food in punishment for her failures, or that somebody has seen Ornuo and Pneio, when she hears the rhythm to it. It’s not somebody come to hurt her. It’s somebody come to ask for help.

She leaves her window perch. She goes down the central spiral of stairs, into the main space of her workroom, with its astrolabes and charts and stuffed curiosities. She ducks below the corkindrill that is suspended from the floor of the loft and creeps toward the door, where the knocking is now accompanied by polite shouts. Her door is barred with a haphazard mix of materials and locks, and she is relieved to see it hold.

Phosyne goes to the series of pipes that feeds through a hole in the wall beside the door. The gap was originally designed to deter attackers, but she is no good with a spear or a sword, so instead, the pipes, with a little window at the end. Inside, a series of mirrors. She can see the whole hall from the safety of a little podium a good five feet to the left of the door.

The king stands just outside her rooms.

She shoves the glass-capped pipe away, then grabs it again, cursing, and peers once more. Yes, it is the king, still in velvet finery even after all these months, a little thinner in the cheeks but not by much. He stands at ease, flanked by guards but not wearing armor himself. He trusts the walls to defend him, and he has not come to kill her.

Silly; the king would never kill her. He has people for that.

So she measures the people: two soldiers, looking furtive and nervous but no more so than usual. Probably not here to kill her either, but the absence of Ser Leodegardis makes her uneasy. She only glancingly knows the king. Leodegardis, responsible for this castle in particular, is responsible for her as well. But a king cannot be denied; she needs to open the door, or else there will be even more trouble.

“Coming! Please wait!” she cries; the pipes should carry her words out of the room. And then she sets about unlocking locks and shifting planks of wood. Her serpents dive beneath rugs, hiding among her piles of texts and tools, more mess in the maelstrom of her room.

She pulls open the door, but doesn’t move out of the way, bowing where she stands. “Your Majesty,” she says to his fine leather shoes.

“My madwoman,” he greets, and his rich voice is pinched thin. (Not yours, she thinks.) “Do you have another miracle for me?”

“Not yet,” she says, wincing. It’s been nearly a month since she solved Aymar’s water problem. In any other circumstances, her work would have been enough to earn her safety and acclaim for years, if not a lifetime. Here, now, it is nowhere near enough.

She sees his shadow shift, feels him lean beyond her, peering into her workspace. “May I observe, Phosyne?”

No. No, he may not. But she can’t refuse a king, and she’s never been skilled at polite dances. So she grimaces and backs up a few steps, finally straightening, hands tugging at the roughspun fabric of her robes. She looks for all the world like a nun, except that where a nun keeps her skull fastidiously close-shaven, her head now shows nearly a year’s worth of shaggy, dark growth, untended and unminded. Her clothing has been leeched of color in several places by experiments gone wrong. She is far thinner than even the privations of the siege demand.

He follows her in with a wave of his hand. His escort remains outside and closes the door after him.

Phosyne has never been alone with a king before. She can’t tell if she’s suffocating under the weight of his presence, or if she’s shocked that he is, in fact, still just a man.

A very tired man, who goes to the stool by one of her workbenches and sits down heavily. He’s picked the more familiar array of her tools to look at, vessels grudgingly loaned to her by the Priory mixed in with her own more-chipped and haphazard implements. He must notice the mess of it all, even in the gloom, but he seems to look right through it. His gaze doesn’t stop on the half-sketched frescoes on her walls, attempts at understanding pigment and form. He does not speak.

Phosyne flinches anyway.

“No progress,” she mutters, eyes averted. “I thought I had something, but—but not yet.”

He sighs. “The quartermaster tells me—”

“Fifteen days,” she accedes. “I know.”

“You have done the impossible for me once,” he says. “Surely it cannot be so hard to do it again?”

Unfortunately, she is fairly sure her first miracle was pure luck. She still doesn’t know where the process came to her from. A dream? A half-remembered theorem from her days at the Priory? But if so, the Priory itself would have solved the problem long ago.

Though—

“Has Prioress Jacynde had any luck?” she asks. “Any progress at all? If I knew where their work stood, I might be able to build on it.” And though the prioress would sneer with disgust if Phosyne came to her directly, even in this time of greatest need, she would not do the same to a king.

“No,” the king says, dashing her hopes. “None at all. They claim it cannot be done. That matter cannot be transformed, that something cannot be brought forth from nothing.”

Phosyne chews her chapped lip to keep herself from arguing. Or, worse yet, agreeing.

She’s still not sure where she stands on the concept.

They are silent for several moments, long enough that Phosyne spies a shifting shadow beneath her other desk—Pneio nosing out from his hiding place. She moves, half a step, to shuffle him back out of sight.

And then he hides himself, and not because of her.

Because of shouting.

It’s muffled by her stoppered windows, but it’s getting louder, and the king raises his head with a haunted, hunted look. Phosyne stares back at him for just a moment, then turns and races up the steps to the loft, crouching to peer out her tiny plate of glass. She expects plumes of dust, jagged wreckage along the walls, the signs of an attack they have been half expecting for weeks now. But the walls are whole, and beyond them, the enemy all but lounges. No assault. No threat from without.

So Phosyne looks within.

A scrum, boiling quickly into a mob, crowds against the short walls that surround the kitchen garden down in the yard.

She sees a flash of metal. It is not a sword.

Not yet.

It’s sun on armor, the blinding reflection of a knight’s breastplate, and the only knights who go about in metal armor inside the walls are the king’s knights. The woman (for the side of her head is shaved, and the remaining dark hair hangs in a braid to her shoulders) has climbed on top of the garden wall, and she bellows for order. The wind steals her words away, but not the sound, and Phosyne is transfixed.

The mob should be afraid. It’s not.

It’s angry.

Somebody throws

a stone.

Shouts become screams as the knight draws her sword and descends into the mob.

From here, Phosyne cannot make out details, can’t see if hands are severed, necks are cut, or if there are only threats and shoves and intimidation. She sees at least three people fall to the ground. She sees other guards wade in, along with the familiar fair head of Ser Leodegardis. Somebody is dragged, kicking and thrashing, out of the maelstrom. The soil grows dark.

The king is by her side, frowning at her makeshift shutters. “What is it?”

“A riot,” Phosyne breathes, eyes wide. And then they grow wider because she sees now who was at the center of the mob, as he is pulled from the crowd, hurried back through the garden, into the kitchen. “They had the quartermaster. They were going to tear him to pieces.”

The king snarls and thrusts Phosyne out of the way, crouching to peer through the glass. The screams are quieting now, and so the action must be too. Only a minute more passes before the king pulls away, running a hand through his hair, tugging his beard.

“Ser Voyne has it in hand,” he grinds out. But he does not sound happy. Unrest will kill them far quicker than starvation.

Phosyne will have to revise her numbers.

“I need my miracle.”

Her shaking worsens. “It can’t be done. I can’t promise that. Food—food is not as easy as water, and water was not easy either. We need something else, another solution. I’m sorry, I can’t—”

“You can,” he says. “You will.” He regards her closely, then the room at large. It is a far cry from the orderly cleanliness of a Priory workshop. She’s not surprised at his grimace.

She thinks that perhaps now he’ll agree, that he won’t believe she can do it either. For the wrong reasons, but if it gets her relief—

“I have clearly been too generous, allowing you to work unobserved, at your own pace. Your success with the water seems to have been born of luck, not labor. Leodegardis had me convinced of your unique point of view, of the necessity of thinking more flexibly, but I think now that Prioress Jacynde had the measure of you. You need a firm hand.”

No.

No, she does not want anybody else in here. There have been miracles, yes, but disasters, too, and she cannot keep disasters hidden if—if—

“Ser Voyne will be your minder,” the king says, and Phosyne looks back down at the tall, broad slab of a woman, all muscles and flashing blade, blazing eyes that Phosyne can feel, even from this height.

“A minder will

not help me,” she says, hunching over herself protectively.

“Ser Voyne will be your minder, and you will find me my miracle. You will feed my people. You will buy us more time. And you will remember that you are here on my sufferance.”

Ser Voyne, still sweat-soaked and itching for a proper fight in the wake of the riot, listens as the rest of the king’s fellows debate the merits of killing their own.

It will free up food for other mouths, the pragmatists say. (They do not say that flesh is flesh, but Voyne sees hunger in their eyes.) The fearful and the faithful say that law and order must be kept, no matter the cost; in the closed system the castle became six months ago, there is no room for chaos. But the loyalists, they cry that there must be as many hands to bear arms as possible when at last the relief comes, when the siege is broken, when they can take back the fields.

This is when Voyne moves forward in her seat, and the room quiets.

“I would agree, except that treasonous hands had best not hold swords,” she says. That earns nods and soft murmurs of assent; after all, she is a war hero. She was at Carcabonne, has seen terrors. She should know.

Does know, she reminds herself, when her confidence falters under the weight of eyes on her, eyes that see her fine armor and her seat at the king’s right hand. They’re listening to her, but perhaps they shouldn’t. Perhaps she’s lost the taste; she hasn’t seen any terrors lately.

The king doesn’t let her get close.

She feels his eyes on her most of all, and so Voyne doesn’t add the more damning rebuttal to the loyalists’ argument that is burning a hole in her breast: that there has been no sign of a relief force, and the chance of them ever leaving these stone walls is so small she can no longer see it.

There will be no taking back the fields, with treasonous hands or not.

Today’s riot is just the beginning.

They were not meant to be pinned down in Aymar, though of course it was constructed for just such a possibility, a strong spur castle on a ridge manned by Ser Leodegardis, his brothers, his household. A garrison of not inconsiderable strength, managed and provisioned well. But even Aymar has its limitations, and feeding so many refugees and knights and servants for six months was never going to be possible, and that is before they consider that the king is here in residence with them with his own sizable retinue. The farms beyond the walls have all been torched and squatted on and turned to shit, and the kitchen gardens, while extensive, have now been picked bare of even the autumn-bearing crops, far too soon. The stores have sustained them this far, but only due to a miscalculation, because they’d all hoped they would be gone long before now.

Relief was supposed to arrive a month ago.

Instead, they are stalemated. They have fended off rounds of attacks from Etrebia, but they have destroyed few of their rams and towers, only fought back hard enough to make them bide their time out of range. Etrebia’s men are entrenched and willing to wait for resupply. Aymar’s inhabitants are prepared only to starve.

Voyne sees all of this, and is furious, and wants nothing more than to ride out herself and force her way through to victory. Instead, she puts down riots and sits at her liege’s side, spoiling for a fight she must not start.

“We need to send another messenger,” Ser Leodegardis says from the king’s other side, fists clenching on the table as he resists the urge to bury his head in his hands. He, too, feels the weight, but

he bears it better. “Before our strength begins to fail. The descent—”

“Is too treacherous,” his cousin, Ser Galleren, snaps. “Why do you think the relief has not come? Every single person we have sent down the cliffside has either died or been captured.”

“One more messenger is one less mouth to feed,” Denisot, the chamberlain, points out. “We lose nothing by trying. A faint chance of hope is better than none at all. And hope may stave off another riot.”

King Cardimir closes his eyes, pinches at the bridge of his nose. “We must provision any messenger we send. We can’t even give them a knife.”

Prioress Jacynde does not flinch, not even when all heads turn to look at her. Her engineers are even now hard at work, trying to manufacture their salvation in exchange for nearly all the iron in Aymar. Every hinge, every pot, and even a fair number of weapons and plows, the dregs that would have been given to the refugees to arm them in an assault. All handed over, melted down, into a new tool that they hope will buy them more time.

Time to starve.

“We must consider,” Jacynde says, “that our messengers have gotten through.”

Silence.

Voyne clenches her jaw. Tight.

Cardimir does not move.

“Prioress,” Leodegardis warns.

“If we refuse to consider all options, we will miss opportunities,” Prioress Jacynde says. “If our messengers have gotten through, and if relief has not come, then we must assume we are too great a risk to rescue.”

The silence cracks, explodes, and there is shouting. Cardimir and Leodegardis share a look, and Voyne considers getting to her feet, joining the fray, with words if not with fists. That need to act boils in her blood. It would feel so good.

It would do no good at all.

The prioress is right, after all. Even if no messenger has gotten through, word must have reached the capital city of Glocain and the princes by now. There should be a relief force.

There is not.

There may never be.

Their army has always been proud, and skilled, and well-funded. They have laid siege, and this is a perversion of the way of things. They know every way that a siege may be won or lost, and yet they have not been able to break their attackers’ lines.

Voyne has marched across every mile of the king’s land. She has led armies to great victories and called for desperate retreats. She knows

that, realistically, there may be no winning move here.

And she knows, too, that whatever happens here is not her responsibility. She does not wear the mantle of a strategist anymore, or even a leader. She is a knight of the king’s guard. It was not her job to prevent this.

But that doesn’t reduce the weight Voyne feels on her shoulders and chest every waking moment, as hunger gnaws at her belly—though not as harshly as it does for others. She is well fed. She sits at the king’s right hand, or near enough, and that comes with perks.

The king reaches for his honeyed wine. He drinks deep. And then he passes the cup to Leodegardis, who sips, and to Voyne, who stares.

“Drink,” he says. “One last comfort, before the horror.”

And she takes the cup and drinks.

After, when the room is quiet and all but empty, she and Ser Leodegardis sit alone in the chamber, heads bowed together over a map. The physical aches and pains of the day have at last made themselves known. She has shed her armor and sent her page away again, and rubs at her aching shoulder through her gambeson.

There is so much to be done, and so little. The chaos and physicality of the riot provided the smallest break in the unending stretch of days endured, and now she is having trouble fitting back into her shell.

“Send me out,” she says, the first time either of them has spoken since the sun set.

“You know I can’t do that,” he says. “Least of all because I have no actual authority over you. His Majesty—”

“His Majesty has kept me useless on a leash for two years,” she interrupts, not looking up from the map, the routes more or less accessible to a clever climber marked out along the topography of the cliff they sit on. She tries not to sound bitter, only practical. She knew (knows) how to be practical. “I am ornamental, not useful.”

“You were useful today. You stopped the riot quickly, without death.”

“But with much frustrated rage,” she points out. “If I remain, that rage may turn to hatred. If you send me away, you may buy peace for another week.”

“Are you a coward, then?”

Voyne flinches, recoils, finally looks up at him. “Excuse me?”

“You’d abandon your king.”

“I would risk my life to save him.”

“But you wouldn’t die by his side.”

Leodegardis holds her gaze in challenge. They are close in age, a difference of no more than three or four years. They have known each other since they were teenagers, perfecting their work with the blade, strengthening their bodies and learning tactics, learning languages. They were heroes together, for a time, planting their flags on conquered battlefields, making

legends of themselves. Now they stare each other down across a vast gulf that grew when they weren’t looking.

In another life, Voyne could have been him. Tasked with the protection of the border, entrusted with a castle, with a span of fields and towns, with the lives and well-being of hundreds, thousands. They both won their king’s favor on the battlefield, earned his trust. They should be equals.

Instead, she is a glorified lapdog. Within besieged walls, she is worthless.

She turns away, finally, bowing her head. “I was mistaken,” she said, throat thick. “But please—please promise me, that if my actions today threaten your control here, that you will remember my offer.”

Leodegardis doesn’t promise, but he also doesn’t foreswear her. “Go rest,” he says instead, offering a tired smile. “It’s almost time for evening service, I think. Perhaps the Lady will grant you some comfort.”

A good suggestion, and kindly meant. She clasps his shoulder, then leaves him to his nightmares. They all feel it, the weight of death bearing down on Aymar, but he is Aymar. They are all about to die, and she is about to fail, but he is about to crumble.

She winds her way through the keep and to the chapel tower. Jacynde’s nuns are indeed hard at work, ready to guide the few parishioners who are here to observe the setting sun. Voyne, grateful, lets the familiar words and hymns wash over her. It isn’t the balm it used to be, back when she was young and idealistic and fervent in her belief that the world could ever be orderly, could ever make sense, but it still soothes her jagged edges. It is a relief, to be reminded that she isn’t alone, is never alone. The Constant Lady always has a hand upon the world.

After, she makes her way up uneven staircases long-since memorized, twists and turns as familiar as the halls she played in as a child. Few rushlights burn, but there is midsummer moonlight streaming through windows, more than enough to guide her by. She steps aside to let a serving girl pass, then takes the final turning to reach what used to be Leodegardis’s room, now given over to Cardimir, to Voyne, to their servants. A little household for the king, shut up in a keep and starving quietly, only a little slower than all the rest.

She slips inside, and is surprised to see Cardimir waiting for her.

He sits by the hearth, where there’s no fire thanks to how warm and sticky the air is. “Come,” he says, voice pitched so as not to wake the servants who have already bedded down in their partitioned section of the room. Voyne goes to him, kneels before him in greeting. He touches her shoulder absently, the one that hurts, the one that is scarred from an arrow she took for him years ago.

“I had forgotten,” he murmurs, “the power of your presence.”

“You saw the riot?” she asks.

“Through the

strangest vantage point,” he says. “What do you know of Leodegardis’s madwoman?”

“The heretic?” she asks. “Very little. Only that she arrived a few months before we did.” It hadn’t felt important to learn more, no matter Leodegardis’s odd affection for the woman.

But the entrance to her tower room is not so far away. Voyne has seen the woman a few times, drawn and furtive and skulking. Her eyes drift in that direction.

“I have charged her with finding a way to restock the quartermaster’s stores,” he says. “Now that our other options have run out.”

Voyne averts her eyes so that she does not stare in horrified disbelief.

“My liege?” Her mistrust colors her words more than she wants it to, but it’s been a long day. A long day of nearly killing desperate, hungry people. She understands, of course. It’s tempting, to hope for an impossible solution, but she had thought her king was better than that. More reasonable.

But it’s also a distraction. They can’t afford distractions.

“I have asked her for a miracle,” Cardimir says.

Voyne bows her head, mastering herself with the reflex of long practice. “I see,” she says. “And what provisions does she demand for such a thing?” If it’s not much, if it’s only a way to keep the woman occupied, perhaps it’s not so bad.

There is so little to do but wait for death now.

“Very little,” he says. Her shoulders ease. “But I want her to have more. I want her to have you.”

Voyne’s head jerks up. She stares, unable to stop herself. “Me.”

“I need you to watch her,” he adds. “Encourage her. She is . . . disorganized. I would see her supported. Given oversight.”

“So that she can conjure food from nothing?” she asks, brow pinching. She searches her king’s face for some scrap of sense. She finds it. He is confident and calm.

That’s a hundred times worse than misguided faith.

“What is a second miracle after a first?” he asks with an indulgent smile that makes Voyne feel small, childlike. She hates that smile, and if she were not so worn down, so stunned, she would bristle at it. Instead, she just shakes her head, helpless, not understanding. He takes pity on her. “She is to be thanked for fixing our water issue last month,” Cardimir says.

Voyne’s world lurches into a new alignment. She frowns. “But the Priory—”

“Agreed to take responsibility, in case there was a problem. And in case it worked. Nobody would have trusted the cisterns if they knew a heretic was responsible for clearing them.” He waves a hand. “She is . . . a wild thing. One of Jacynde’s order, originally, but strayed. Jacynde hates her, but Leodegardis is adamant in his patronage, and she has paid her way

admirably so far.”

That gives her pause.

Because the water issue of last month was also an impossible solution to an impossible problem. Aymar’s location was strong, but its strength had nearly been their undoing. Built on a rocky outcropping, the castle’s only source of water was rain and a single well in the lower yard. The rains had stopped months ago as summer rolled in. The cisterns had begun to dry out, so they’d hauled water up and out, up and out, before the well could dry, too.

With that water, so desperately needed, had come pestilence. It had begun slowly, a few children beginning to vomit, low fevers rolling through, and in their meetings, they had steeled themselves for the sorts of illness that spread among the closely packed. They let the Priory step in, begin segregating the ill, treating them, fumigating the castle with cloying incense.

They had known, at least, that it couldn’t be the water. Water pulled from stone was clean. The cisterns were capped and guarded. It couldn’t be the water.

But it was.

As the well’s level had dropped, the water had turned foul, and they had spread that foulness to every cistern. At first, the water had tasted normal, had looked clear, but eventually the buckets they hauled up stank of shit. There was no other water.

And then, a miracle. Jacynde’s nuns had created a powder that, when mixed with the water, caused the water to heave and shudder and shine with wondrous colors, before finally turning clear and odorless again. Leodegardis had ordered his household to test the cleared water themselves, and when they did not sicken further, when they grew hale once more, the cisterns were cleared.

Voyne reflects that she has not actually tasted the cleared cistern water; there is another tank, one that captured rain before the summer began to dry, that lives just below the madwoman’s room. It delivers clean water via a pipe into the kitchen, and Cardimir drinks from it exclusively, as does she.

Just in case.

Knowing now that it was not the Priory that solved their woes, but this strange, gaunt wraith of a woman who has somehow bewitched her king, Voyne is glad for their caution.

She scrubs at her face, sitting back on her heels. “What of the Priory’s new invention?” she asks, testing out the new landscape beneath her. “Do we also have this madwoman to thank for taking our iron from us?”

Leaving us ill-armed to repel an attack? she does not add.

“That was Jacynde’s order,” the king assures, and the world slows its spin, settling into its new configuration with a groan. It’s only a little off-kilter. “But I do not doubt she could have derived something similar. And until Etrebia strikes again, we have far more need of food. You know this, Ser Voyne.”

“I do, my liege,” she says, then takes a deep breath. Tries

to be grateful for the clean water, hopeful for miracles. It does not sit well in her practical breast, which burns instead for a blade, a battle plan.

This will have to suffice.

“What will you have me do?” she asks.

“Her name is Phosyne,” Cardimir tells her. “I want you to go to her tomorrow. Do not let her out of your sight, and do not let her remain idle. Reassure me that she is working as hard as she can. We have only enough time for results.”

She wants to say no, wants instead to ask him to send her away as a messenger. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...