Chapter 1

The last time I spoke to my brother was six months ago. I remember the date exactly: the twenty-second of April, 1883. How could I not? It’s burned into me like a cauterized wound, an artery seared shut to keep from bleeding out.

It was his wedding, and I was on the edge of hysterics.

I wasn’t being difficult on purpose. I wasn’t, I swear. I never mean to be, no matter what Mother and Father say. I’d even promised it would be a good day. I wouldn’t let the too-tight corset send me into a fit, I wouldn’t tap, I wouldn’t fidget, and I certainly wouldn’t wince at the church organ’s high notes. I would be so perfect that my parents wouldn’t have a reason to so much as look at me.

And why shouldn’t it have been a good day? It was my brother’s wedding. He’d just returned to London after a few months teaching surgery in Bristol, and all I wanted was to hang off his arm and chatter about articles in the latest Edinburgh Medical Journal. He would tell me about his new research and the grossest thing he’d seen after cutting someone open. He’d quiz me as he fixed his hair before the ceremony. “Name all the bones of the hand,” he’d say. “You have been studying your anatomy, haven’t you?”

It would be a good day. I’d promised.

But that was easy to promise in the safety of my room when the day had not yet started. It was another to walk into St. John’s after Mother and Father had spent the carriage ride informing me I’d be married by the new year.

“It’s time,” Mother said, taking my hand and squeezing—putting too much pressure on the metacarpals, the proximal phalanges. “Sixteen is the perfect age for a girl as pretty as you.”

What she meant was, “For a girl with eyes like yours.” Also, it wasn’t. The legal marriageable age was, and still is, twenty-one, but the laws of England and the Church have never stopped the Speakers from taking what they want. And it was clear what they wanted was me.

It was like the ceremony became a fatal allergen. While Father talked with a colleague between the pews and Mother cooed over her friends’ dresses, I dug my fingers into my neck to ensure my trachea hadn’t swollen. The organist hunched over the keys and played a single note that hit my eardrums like a needle. Too many people talked at once. Too loud, too crowded, too warm. The heel of my shoe clicked against the floor in a nervous skitter. Tap tap tap tap.

Father grabbed my arm, lowered his voice. “Stop that. The thing you’re doing with your foot, stop it.”

I stopped. “Sorry.”

On a good day, I could stomach big events like this. Parties, festivals, fancy dinners. Sometimes I even convinced myself I liked them, when George was there to protect me. But that’s only because a legion of expensive tutors had trained me to. They’d molded me from a strange, feral child into an obedient daughter who sat with her feet tucked daintily and never spoke out of turn. So, yes. Maybe, if it had been a good day, I could have done it. But good days had suddenly become impossible.

In the crowd, I slipped away.

Sometimes I pretend my fear is a little rabbit in my chest. It’s the sort of rabbit my brother’s school tests their techniques on, with grey fur and dark eyes, and it hides underneath my sternum beside the heart.

Mother and Father are going to do this to you, it reminded me. I pressed a hand against my chest as I searched the pews to no avail. The church was long, with stained glass stretching up like translucent membranes. And when they do, you’ll cut yourself open. You’ll pull out your insides. You promised.

I stepped out into the vestibule, and after all this time, there he was. My brother with

his groomsmen, friends from university I’d never met. Stealing a drink from a flask. Swinging his arms, trying to get blood to his fingers. Bristol had changed him. Or maybe he’d just matured while I wasn’t there to see it, and it’d be better if I turned him inside out and sewed him up in reverse so I no longer had to watch him age. At least, now that he was back, he’d be serving the local hospitals and nearby villages, and he wouldn’t be so far away from me. Nothing all the way out at the coast, not anymore.

I said, barely loud enough to hear, “George?”

My brother met my eyes, and his first words to me in months were, “That’s the dress you picked?”

Right. I’d tried awfully hard to forget what I was wearing. The corset was specifically made to accentuate curves and the dress was gaudy, with a big rump of a bustle as was the fashion. Or Mother’s idea of the fashion. I’d studied diagrams from George’s notes of how tightlacing corsets could deform bones and internal organs, memorized them until I could draw them on the church floor with charcoal. Flesh and bone make more sense to me than the people they add up to.

“It was Mother’s idea,” I said plainly, resisting the urge to chew a hangnail. “May I speak to you? For just a second?”

George flashed a grin at his groomsmen. “Sorry, lads. The sister’s more important than you lot.”

So he broke away from the flock, even as his friends groused and jabbed their elbows into his ribs—and then he led me to a quiet corner in the back of the sanctuary. Away from the people and the noise.

Without Father to snap at me, I couldn’t stop fidgeting. My hands wrung awkwardly at my stomach, and I bit my cheek until I tasted blood.

It’s pathetic you ever thought you’d avoid this, the rabbit said.

George got my attention by putting a hand in front of my face. “In,” he said. I scrambled to follow his instructions, breathed in. “Out.” I breathed out. “There we go. It’s okay. I’m here.”

As soon as you were born with a womb, you were fucked.

I couldn’t take it anymore. The mask I’d built to be the perfect daughter cracked. The stitches popped. I began to cry.

George said, “Oh, Silas.” My name. My real name. It’d been so long since someone called me my real name. I clamped a hand to my lips to stifle an embarrassing gasp. “Use your words,” George said. “Tell me what’s wrong.”

I didn’t mean to do this at his wedding. I didn’t do it on purpose. I didn’t, I swear.

I said, “I need to get out of that house. It’s happening. Soon.” I started to rock back

and forth. George put a hand on my shoulder to hold me still, but I pushed him away. I had to move. I’d scream if I couldn’t move. “No. Don’t. Please don’t. I just—I don’t know, I don’t know what to do.”

“Silas,” George said.

“If I get away from them, I could buy a little more time.” Could I, though? Or was I just desperate? “Don’t leave me alone with them, please—“

“Silas.”

I forced myself to look at him. My chest hitched. “What?”

Then, one of the groomsmen, leaning out to the pews, bellowed: “The bride has arrived!”

“Shit,” George said. “Already?”

“Wait.” I grabbed for his sleeve. No, he couldn’t walk away now, he couldn’t. “George, please.”

But he was backing up, peeling me from his arm. When I remember this moment months later, I recall his pained expression, the worry wrinkling his face, but I don’t know if it was actually there. I cannot convince myself I hadn’t created it in the weeks that followed.

“We can talk about this later,” George said. “Okay? Sit, before someone comes looking for you.” Nausea climbed up my throat and threatened to spill onto my tongue. “Afterwards. I swear.”

He walked away.

I stared after him. Still shivering. Still struggling for air.

What else was I to do except what I was told? I never learned how to do anything else.

I scrubbed my eyes dry and found my place with our parents. Mother smiled, holding me by the shoulder the way surgeons used to hold down patients before anesthesia. “How is George doing?” she asked me, and I said, “He’s well.” The organist ambled into a slow, lovely song, and the sun shone through stained glass in a beam of rainbows. George stood at the end of the aisle. He met my gaze and smiled. I smiled back. It wavered.

The bride herself, when she walked in on her father’s arm, was tall, with honey-colored hair. She was not the most beautiful woman in the empire, but she didn’t have to be. She radiated such kindness that it was as if she were made of gold.

But.

She had violet eyes.

And a silver Speaker ring on her little finger.

The rabbit said, Soon, that will be you.

When I was younger—ten, I think, or maybe eleven—I dreamed of amputating my eyes. It seemed easy. Stick your thumb in the socket, work it behind the eyeball, and take it out, pop, like the cork in a bottle of wine. If they were gone, I reasoned, the Royal Speaker Society would leave me be. They came over every Sunday

to savor cups of Mother’s tea, talk with Father about ghosts and spirit-work and economic ventures in India, and calculate the likelihood of their children having violet eyes if they had those children with me. “You’ve never played with a ghost, have you?” a Speaker said once, teasing my sleeve. “Because you know what happens to little girls who play with ghosts.”

And it has never stopped. It has only gotten worse, louder and louder as I grew into my chest and hips. Now they kiss my knuckles and run their hands through my hair. They wonder about boys I’ve been with and offer ungodly sums of money for my hand in marriage.

“Is she lilac, heather, or mauve?“ they would ask my mother, holding my jaw to keep my head still. Sometimes they gave me their silver Speaker ring to wear, just to see how I’d look with it one day. “Oh, Mrs. Bell, when will you let her marry?“

Mother would just smile. “Soon.“

I’d grown out of the juvenile fantasy quickly enough. The eyes were a symptom, not the disease. If I wanted to resort to surgery, I’d have to go to the root: a hysterectomy, a total removal of the womb. Until my ability to continue a bloodline is destroyed, these men don’t care how many pieces of myself I hack off—but that doesn’t mean I haven’t popped the eyes out of a slaughtered pig just to feel it.

George’s wife had violet eyes like mine.

He was doing to a girl everything that would be done to me.

I got up from the pew. Mother hissed and reached for me, but I stumbled into the aisle, clamping a hand over my mouth. I slammed out the front doors and collapsed onto the stairs.

I spat stomach acid once, twice, before I vomited.

Father came out behind me, dragging me onto my feet. “What are you doing?” he snarled. “What is wrong with you?”

It will hurt, the rabbit

said. It will hurt it will hurt it will hurt.

George has not been able to face me since.

He knows what he did.

Chapter 2

November descends upon England, dark and uncaring like consumption, and I’m almost grateful; after all, it is easier to be a boy in the winter.

I fret in front of the vanity mirror as embers gleam in my bedroom fireplace. Darker tones are blessedly more fashionable in the later months; heavier fabrics and long coats break up the silhouette, obscuring more feminine features. There’s nothing to be done about soft cheeks and pink lips, but with my hair tucked into a cap and a scarf wrapped round to conceal the pins, I just about pass for a boy. A feminine, baby-faced boy from the poor side of the city—funny, then, that my bedroom is full of fine dresses and imported rugs—but a boy nonetheless. Very Oliver Twist. I think. I’ve never been one for stories.

Still, my chest aches as I fill out my brows with powder stolen from Mother’s vanity. How cruel is it, that I only get to be myself as a costume? I do not get to savor the masculine cut of my clothes, or the illusion of short hair, or the fleeting joy of my skin feeling like mine. Instead, I have to worry if my boyhood is convincing enough to keep me safe. There is no joy in that. Only fear.

You think you’ll fool them? the rabbit chides as I work. So many men would do terrible things for you. So many of them have begged for the chance. They’d know your body anywhere. Look at the trousers bunching at my full hips and the linens tied around my breasts that never feel tight enough. See? You’re nothing more than a little girl playing dress-up.

And you’re going to walk right into their lair.

The rabbit is right. If I have any time left, it’s not much. Mother and Father have nearly decided on my husband. That’s what they’re doing at this very moment: perusing the Viscount Luckenbill’s annual Speaker gala with a list of names. This year’s costume theme is literature, so they’re busy in whatever inane outfits Mother has devised, cross-examining the men who have fawned over me all my life. I can nearly hear them weighing the advantages of each potential marriage contract. How many connections do they have? How much money? How much power?

So, yes, it would be safer to stay home. But tonight is my best, and maybe my only, chance to escape.

Because a young medium is set to receive his spirit-work seal at the gala tonight—and with any luck, it will be me. The plan is simple enough. Go to the gala, get the seal, and run.

I close the tin of powder and remind myself to breathe.

I do not give a shit about being a medium. I want nothing to do with the Speakers, or spirits, or hauntings, or any of it. But if a silver Speaker ring marks you as a member of the brotherhood, a medium’s seal grants you the freedom of a king. Violet eyes make spirit-work possible, and a seal makes it legal. Speaker money will fund your travels and businesses. Opportunities rise up to meet your feet. Of course, England regulates its mediums brutally, but to be officially recognized as one with that mark on your hand—it might as well be magic, the way the empire will bend for you.

So I’ll take the seal, proof of my manhood branded on the back of my hand, and go where no one knows my face. I’ll enroll in medical school and begin my life in earnest. Nobody will know I had been a daughter once. I won’t need Mother and Father. I won’t need George; I won’t need any of them.

I’ll be…

My heel clicks again, tap tap tap, but it’s not enough to get rid of the tension creeping up my trapezius muscles. In a burst, my hands flutter, and I shake myself out until I’m calm enough to breathe again.

After this, I’ll be free.

I’ve forged my invitation to the gala. According to Mother’s friends, the young man who is supposed to get his medium’s seal tonight, who has eyes like wisteria and traveled all the way here from York for the chance, has fallen ill. Nobody has met him in person, so I’ve borrowed

his name for the evening. I will take his place, and his seal, and I will be gone before a soul learns the truth.

It’s just that if I’m caught, if they figure out who I am, that I was born a girl—

They’ll fucking hang you.

The gala is not far. I slip down the front steps of my family’s townhome—not nearly as impressive as some of the other houses of London, but still grand enough to reflect well on the family—and huddle into my coat. Despite the cold, I refuse to hail a cab. I need to walk. It’s the only way I can reliably clear my head these days. Especially since I don’t let my hands flap in public. “You look like an imbecile,” Father said once, which was far more effective than any of my tutors’ attempts to get me to stop. “You look stupid, girl.“

I tried telling my family the truth exactly once. When I was younger, back when I thought they still cared, I told them I did not ever want to be married. Stories that took the shape of fairy tales sounded like Hell to me. My eyes would give me a good marriage and a life of privilege, a life of plenty, if I’d only let them. But wedding dresses, big bellies, the miracle of childbirth? I’d rather cut myself open. I told them I didn’t want any of it. I told them I was scared.

Mother called me silly, and Father told me to get over it. I knew what they really meant, though. The rabbit translated for me. Entitled. Selfish. How dare I ask to be treated differently than anyone else? Every man and woman in England has a duty, and I couldn’t expect to escape mine just because I was scared.

I don’t think scared was the word I should have used.

It doesn’t take long to find the South Kensington Museum. It’s a grand cathedral of art and finery, lit up so brightly against the dark night sky it looks like it’s been set on fire. The Speakers have swallowed it whole. Violet banners hang from the marble façade, framed by thousands of lavenders and lilacs woven into wreaths and ivy arches, all of which will shrivel and die in the cold as soon as the event is done. Carriages wait obediently in the street, horses huffing and puffing while the drivers try to catch a nap. It’s almost as if the Royal Speaker Society will dissolve into violent chaos if they don’t spend half their taxpayer funding on decorations and overworked servants.

At the entrance, a violet-eyed doorman blows into his hands to warm them. He has a seal, but only a small placeholder design, a circle freeze-burned onto the back of his hand. This is an indentured medium: a man who couldn’t afford his full medium’s seal and so signed himself away to the Speakers in exchange for the funds. It’s a nasty deal, but there will never be a shortage of people willing to take nasty deals in exchange for a better life. This indentured medium will get the rest of the seal, an intricate eye, once his debt is paid off—as long as the hand doesn’t succumb to gangrene first. At least he gets to wear a fancy ring while he waits.

Through the twin sets of double doors, I hear laughter. It’s muffled, as if underwater. I’m late.

“This is a private event, boy,” the doorman drawls as I approach. There’s a thrill at being accepted as male, but I refuse to let myself linger on it. It doesn’t matter nearly as much if they’re seeing the wrong boy.

“I’m aware,” I say, and produce the invitation.

The doorman frowns, skimming the forged document up and down. His eyes are droopy and his hands seem to be permanently stiff. “Roswell? My, uh, sincere apologies. Glad those rumors about you being ill were just rumors.” He doesn’t sound particularly glad. “Well, they haven’t started the ceremony yet, so you’re in luck. Mors vincit omnia and all that. Come in.”

He opens the door.

I hate that anything having to do with the Speakers could be beautiful. Inside, a towering ceiling looms toward marble balconies; gas lights flicker, turning everything gold. Irreplaceable works of art have been brought out for the occasion, placed behind tables overflowing with purple bouquets. The air smells of liquor and pollen and ozone. And the costumes—a woman with cheeks painted pink in homage to Heidi. An Edgar Allan Poe carries a model heart. Some bored-looking man has opted out of the theme by carrying around a portrait of a horse, claiming to be one character or another from Black Beauty. So many glimmering silver rings, a smattering of seals, too much drinking and laughing and noise. It is so overwhelmingly jovial in comparison to the sick feeling in my stomach. The mismatch makes me want to dig my nails into my arms. It’s just like the wedding all over again. I hate it, I hate it.

Just walk away, the rabbit says. You don’t belong here and you know it. Leave. Go.

But I don’t leave. I can’t. As I step into the museum, I imagine the branding iron so cold it smokes in the air. It will crackle and hiss as it touches my skin. The pain will be worth it in exchange for the freedom it will grant.

I have to do this.

The doorman steps in behind me, ushered by a gust of air so frigid that I turn to make sure a spirit hasn’t followed him.

“George Bell?” he says. ...

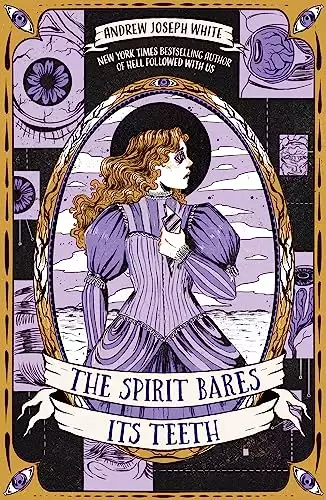

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved