SHE WAS WEARING a straw hat, pulled down over her forehead, a short flowered dress, no stockings and white high heels. A lot of blond hair showed under the hat. Her face was nearly angelic and looked about 15, though the fact that she wore a wedding ring made me skeptical. She marched into my office like someone volunteering for active duty, and sat in one of my client chairs with her feet flat on the floor and her knees together. Nice knees.

“You’re Mr. Spenser.”

“I am.”

“Lieutenant Samuelson of the Los Angeles Police Department said I should talk to you.”

“He’s right,” I said.

“You know about this already?”

“No,” I said. “I just think everybody should talk to me.”

“Oh, yes . . . My name is Mary Lou Buckman.”

“How do you do Mrs. Buckman.”

“Fine, thank you.”

She was quiet for a moment, as if she wasn’t quite sure what she should do next. I didn’t know either, so I sat and waited. Her bare legs were tan. Not tan as if she’d slathered them with oil and baked in the sun—tan as if she’d spent time outdoors in shorts. Her eyes were as big as Susan’s, and bright blue.

Finally she said, “I would like to hire you.”

“Okay.”

“Don’t you want to know more than that?”

“I wanted to start on a positive note,” I said.

“I don’t know if you’re serious or if you’re laughing at me,” she said.

“I’m not always sure myself,” I said. “What would you like me to do?”

She took a deep breath.

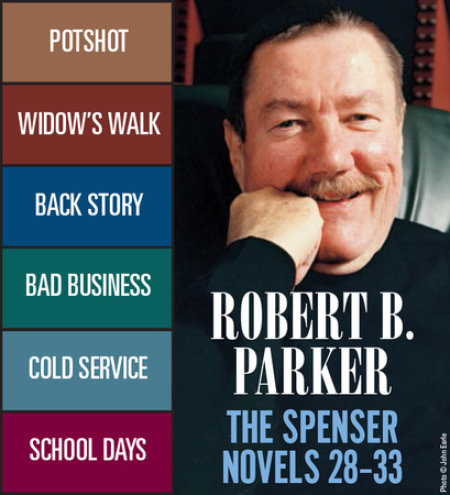

“I live in a small town in the foothills of the Sawtooth Mountains, called Potshot. Once it was a rendezvous for mountain men, now it’s a western retreat for a lot of people, mostly from L.A., with money, who’ve moved there with the idea of getting their lives back into a more fundamental rhythm.”

“Back out of all this now too much for us,” I said.

“That’s a poem or something,” she said.

“Frost,” I said.

She nodded.

“My husband and I came from Los Angeles. He was a football coach, Fairfax High. We got sick of the life and moved out here, there actually. We run, ran, a little tourist service, take people on horseback into the mountains and back—nothing fancy, day trips, maybe a picnic lunch.”

“‘We ran a service’?” I said.

“I still run it. My husband is dead.”

She said it as calmly as if I’d asked his name. No effect.

I nodded.

“There was always an element to the town,” she said. “I suppose you could call it a criminal element—they tended to congregate in the hills above town, a place called the Dell. There’s an old mine there that somebody started once, and they never found anything and abandoned it, along with the mine buildings. They are, I suppose, sort of contemporary mountain men, people who made a living from the mountains. You know, fur trapping, hunting, scavenging. I think there are people still looking for gold, or silver, or whatever they think is in there—I don’t know anything about mining. Some people have been laid off from the lumber companies, or the strip mines, there’s a few leftover hippies, and a general assortment of panhandlers and drunks and potheads.”

“Which probably interferes with the natural rhythm of it all,” I said.

“They were no more bothersome than any fringe people in any place,” she said, “until about three years ago.”

“What happened three years ago?”

“They got organized,” she said. “They became a gang.”

“Who organized them?”

“I don’t know his real name. He calls himself The Preacher.”

“Is he a preacher?”

“I don’t know. I think so. I don’t think he’s being ironic.”

“And there’s a problem,” I said.

“The gang lives off the town. They require the businessmen to pay protection. They use the stores and the restaurants and bars and don’t pay. They acquire businesses in town for less than they’re worth by driving out the owners. They bully the men. Bother the women.”

“Cops?”

“We have a police chief. He’s a pleasant man. Very likable. But he does nothing. I don’t know if he’s been bribed, or if he’s afraid or both.”

“Sheriff’s Department?”

“The sheriff’s deputies come out, if they’re called,” she said. “But it’s a long way and when they arrive, there are never any witnesses.”

“So why are you telling me all this?”

She shifted in her chair, and pulled the hem of her skirt down as if she could cover her knees, which she couldn’t. She didn’t seem to be wearing any perfume, but she generated a small scent of expensive soap.

“They killed my husband.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“He was in the Marine Corps. He played football in college,” she said. “He was a very courageous man. An entirely wonderful man.”

Her voice was flat and without inflection, as if she were reciting something she’d memorized.

“He wouldn’t pay the Dell any money,” she said. “So they killed him.”

“Witnesses?”

“No one has come forward.”

“How do you know it was the, ah, Dell?” I said.

“They threatened him, if he didn’t pay. Who else would it be?”

“And you want me to find out which one did it?”

“Yes and see that they go to jail.”

“Can you pay?”

“Yes. Up to a point.”

“We’ll come in under the point,” I said.

She shifted in her chair again and crossed her legs, and rested her folded hands on her thigh.

“Why didn’t you just sell and get out?” I said. “Move to Park City or someplace?”

“There’s no market for homes anymore. No one wants to move there because of the Dell gang.”

“And you knew Samuelson from your L.A. days.”

“His son played for Steve . . . my husband.”

“And you asked him about getting some help and he suggested me.”

“Yes. He said you were good and you’d keep your word.”

“A good description,” I said.

“He also said you were too sure of yourself. And not as funny as you thought you were.”

“Well he’s wrong on the last one,” I said. “But no need to argue.”

“Will you do it?”

“Okay,” I said.

“Just like that?”

“Yep.”

“What are you going to do?”

“Come out and poke around.”

“That’s all?”

“It’s a start,” I said.

chapter

POTSHOT WAS IN a valley in the early stages of ascending foothills, which became at some indeterminate point the Sawtooth Mountains. There were ostentatious homes above the town. The town was expensive faux western with wooden sidewalks and places with names like The Rattlesnake Cafe and the Coyote Grill. There was a three-story hotel that called itself The Jack Rabbit Inn. It had a wide front porch. Inside, the first floor had a registration desk, a restaurant and a bar in the lobby. To the right of the registration desk there was an open stairway leading up to the bedrooms. My room was one flight up and my window looked down on the main drag. The street was nearly empty. A man and woman wearing cowboy hats over two-hundred-dollar haircuts crossed the street below my window. They got into a Range Rover complete with brush gear. The spirit of the old West.

One of Spenser’s rules of detection is: Never poke around on an empty stomach. So I unpacked, got my gun, and went down for a club sandwich and a draft beer at the near-empty bar in the lobby. The bartender was a slim guy with a ponytail. He was wearing a western-style shirt, and kept himself busy slicing lemons and putting them in a jar.

“I hear you have some trouble around here,” I said.

He stared at me as though I had just told him I was going to shoot myself in the forehead.

“Like what?” he said.

“Like the gang from the Dell,” I said.

“I don’t know anything about it,” he said.

“You know The Preacher?” I said.

“Nope.”

“Guy named Steve Buckman got killed awhile back. You know what happened?”

“You a cop or something?”

“Or something,” I said.

“I already told Dean all I know—which is nothing.”

“Dean?”

“The chief of police.”

“So you don’t know anything,” I said. “Got any guesses?”

“No.”

The bartender went back to his lemons. I finished the club sandwich.

“Do you know how to make a vodka gimlet?” I said.

The bartender finished slicing a lemon and looked up at me.

“Sure,” he said. “You want one?”

I got up from the bar.

“No,” I said. “I just wanted to end the conversation on a positive note.”

Outside, the heat was astonishing. I walked past a sporting goods store with fishing rods and nets and waders and tackle boxes in the window. I went in and felt the welcome shock of the air-conditioning. The front of the store was devoted to fishing tackle and hunting knives. In the back it was guns. There was a rack of expensive hunting rifles across the back wall. Along the side wall was an array of shotguns. And in the glass display case under the counter was a collection of big-caliber single-action western-style handguns. There were elaborate tooled leather gunbelts and holsters for sale. And ammunition and self-loading equipment and cleaning kits.

The clerk wore a red plaid shirt with a string tie held by a silver clip. I leaned my forearms on the counter above the handgun display.

“Sell many of these?” I said.

“Some.”

“I’m new around here. What do I need to have in order to buy a handgun?”

“Proof of residency,” the clerk said. “Like a driver’s license.”

“Same for the long guns?” I said.

“You bet. Care to look at anything?”

“My driver’s license is from another state,” I said.

“We can ship anything you buy to a dealer in your area.”

“Who buys the handguns?”

The clerk frowned.

“Hell,” he said. “I don’t know. They got a local driver’s license, I sell them a gun. I don’t care who they are. Why would I?”

“No reason,” I said. “I was just wondering who would want to pack one of these Howitzers.”

The clerk shrugged.

“Maybe the guy who killed Steve Buckman,” I said.

“He was shot with a nine,” the clerk said.

“By whom?”

The clerk shrugged.

“Why you asking me?”

“You’re here.”

“Yeah, but why are you interested,” he said.

“Just a curious guy,” I said.

He shook his head as if I were ridiculous, and moved down the counter to another customer. His interest in me had plummeted. I didn’t mind. I was used to it. When I left the store the heat was tangible, like walking into a wall. I turned left and strolled the boardwalk. No one was about in the implacable sunshine, except me. Mad dogs and Englishmen, I thought.

In all directions but west, the hills rose up from the town in slow, curved slopes until, distantly, they became mountains. It produced the odd effect of simultaneous vastness and enclosure. I felt as far from home as I’d ever been, which was an illusion. California was farther, and Korea was much farther. But the land was so different, so un-Eastern, and, maybe more to the point, Susan wasn’t here. She hadn’t been in Korea either, but I hadn’t known her then, and, while not knowing her made a hole in my existence, I didn’t know it at the time.

At the end of the main drag, across the street from a western-wear shop and next to a place called Ringo’s Retreat was a small building made of beige bricks with a hip roof and a blue light and a sign outside that said POLICE. I went in.

It was one air-conditioned room. Two cells across the back. A Winchester rifle and a Smith & Wesson pump gun were locked in a cabinet behind a big oak desk with an engraved brass sign on it that said CHIEF. At the desk, wearing a khaki police uniform, was a rangy guy with blond hair and soft blue eyes.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved