PART ONE

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

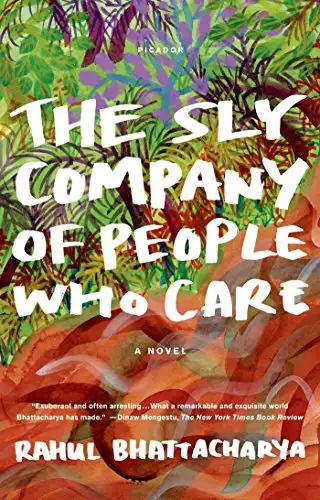

The Sly Company of People Who Care

Rahul Bhattacharya

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved

Close