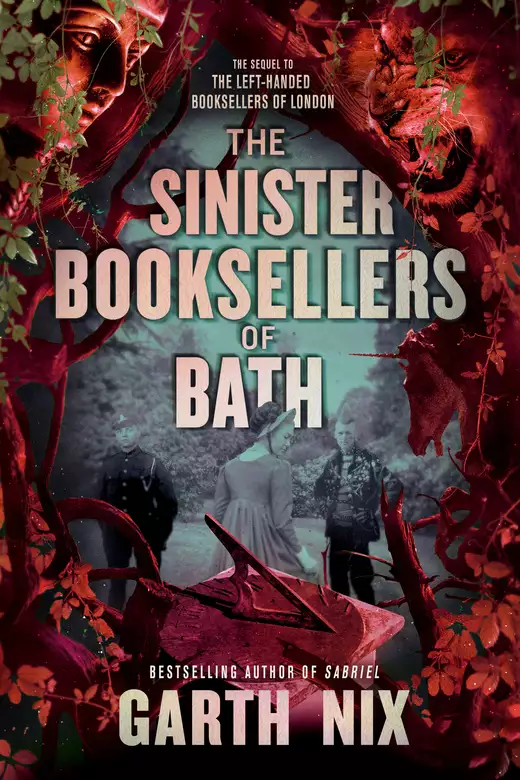

The Sinister Booksellers of Bath

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

There is often trouble of a mythical sort in Bath. The booksellers who police the Old World keep a careful watch there, particularly on the entity who inhabits the ancient hot spring. Yet this time it is not from Sulis Minerva that trouble starts. It comes from the discovery of a sorcerous map, leading left-handed bookseller Merlin into great danger. A desperate rescue is attempted by his sister the right-handed bookseller, Vivien, and their friend, art student Susan Arkshaw, who is still struggling to deal with her own recently discovered magical heritage. The map takes the trio to a place separated from this world, maintained by deadly sorcery performed by an ancient sovereign and guarded by monstrous living statues of Portland Stone. But this is only the beginning. But this is only the beginning. To unravel the secrets of a murderous Ancient Sovereign, the booksellers must investigate centuries of disappearances and deaths. If they do not stop her, she will soon kill again. And this time, her target is not an ordinary mortal.

Release date: March 21, 2023

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Sinister Booksellers of Bath

Garth Nix

THE YOUNG MAN RUNNING PANICKED IN THE DARK INSTINCTIVELY headed towards the Abbey. The streetlights had snapped out a minute before, and he had been suddenly attacked. Something immensely strong had grabbed him in the darkness, lifting him from the bandstand where he’d been slumped trying to work out how drunk he was and what to do since Wednesday night was about to become Thursday morning and everywhere he could get another drink was either closed or wouldn’t let him in.

He’d only escaped because he was wearing his coat like a cloak, his arms not in it, and whatever grabbed him had been momentarily confused as he slithered out of the two-pound Oxfam woolly bargain like a lizard leaving its sacrificial tail in a predator’s mouth.

He took the steps up and out of the park without slowing and vaulted the locked gates at the top without pause, heading towards the Abbey because he knew with absolute conviction that whatever was after him was not human, and though he had never thought of himself as religious before and had stopped going to church with his mum when he was twelve, he had experienced a sudden resurgence of faith. The Abbey seemed the only place that might offer him shelter from whatever it was that came so swiftly after him now. So swiftly, and without normal footfalls. Instead it made sharp scraping sounds all too like a butcher’s knife being rapidly sharpened on a steel.

The three-quarter moon provided what little light there was, limning the dark shadow of the Abbey ahead with lines of silver. The paving stones were rimed with frost, and slippery underfoot, and he almost fell as he reached the massive corner of the medieval edifice and raced around it and along the southern side. He was now astonishingly sober and incredibly frightened.

“Help!” he screamed into the darkness. “Help! Someone help me!”

It was typical there was no one around to help. Two rozzers had stopped their patrol car to look down at him from Pierrepont Street an hour ago, but they hadn’t bothered getting out of their nice warm vehicle and into the cold and drizzle. They’d looked because he was a punk with an orange mohawk and a safety pin through his nose, in a once-good black overcoat splattered with runny drawings in white housepaint, which he thought were anarchist symbols but meant something else entirely. But he was by himself, and a weedy drunken punk slumped on the bandstand in Parade Gardens wasn’t a bother to anyone. He’d been glad they’d left him alone, he never wanted any attention from the police, but where were they now?

In his heart he knew the police wouldn’t be any help anyway. But he shouted again, not slowing his headlong rush along the side of the Abbey. He had a vague memory the main entrance was right up the other end, and the doors were probably closed anyway. But if he could get there, surely a church would be safe, maybe even the front steps would work, but the thing chasing him was too close, that horrible scraping sound was louder and louder—

A cold hand gripped him and yanked him back. A hand colder than the winter air. This time, he was taken by the neck, not by clothing he could shuck. He tried to free himself, reaching back to break the thing’s grip, and thrashed his body with all his strength. But it was not enough, far from enough. He couldn’t escape and he couldn’t breathe. He kicked back at the thing’s legs, pain blossoming in his heels. It felt like he’d kicked the stone walls of the Abbey rather than the creature that held him, but he knew he hadn’t.

The grip on his throat eased a little and he managed to get in a gasp of air. His attacker dragged him away from the Abbey, lifting him as if he were no more than a stick of wood, and took him across the Abbey Churchyard. With every step, there came that horrible, scraping sound. Shk, shk, shk, shk . . .

They came out of the shadow of the Abbey into the moonlight. The punk twisted his head around enough to see his captor and wished he hadn’t. He was held by the neck in an unbreakable grip by something that had the general outward appearance of a woman. One who stood seven feet tall and whose skin was grey and smooth, but weirdly mottled, as if thousands of tiny fossilized shells had been merged together and made into dark marble. Living stone, if that was possible. Her fierce, colorless eyes moved and her mouth twitched, apparen

tly in irritation. She was clad in a simple cross-hatched-patterned dress with a high waist and puffed sleeves, all also of impossibly flexible, moving stone.

She had no feet. Her legs ended in broken stumps at the ankle, jagged breaks, and that was why she made the horrible sharpening noise as she moved, stone upon stone.

The grey stone woman stopped in the full light of the moon and shook out the folded paper she held in her right hand. An old, time-yellowed paper or parchment, the only thing about her that was not stone. It was a map of some kind. For a moment he hoped she might let go of him in order to unfold it properly. But she didn’t. She shook the map once, twice, then held it up so the moonlight fell on it, and it began to glow with its own radiance.

As she did so, the punk caught a metallic, sulfurous whiff. For a moment, he thought it somehow came from the illuminated map. Then he heard water gushing and saw wafts of steam rising from the narrow gaps between the paving stones. The stone woman opened her mouth and emitted a growl, the first even faintly human noise she’d made.

“You trespass on my demesne,” said another woman, one the punk couldn’t see. There was a lot of steam around now, and the iron stench was strong. Hot water rose up between the flagstones, water stained an orange-red, a sudden flood that streamed around the marble woman’s sharp stumps.

Everything became cloaked in steam, and the punk blinked and grimaced, trying to see. But there was only more strangeness, a figure appearing with a face of beaten gold upon a vaguely defined body woven of steam and rusty water. The golden face was curiously familiar. He had seen it somewhere before.

“I have taken my prey and now I will depart,” said the stone woman. Her voice was very strange, echoing and distant, as if it came from a hole beneath the ground.

“I did not give you leave to hunt here. You were warned and punished, when last you trespassed on my demesne,” said the golden face. Her hair was plaited into a kind of crown and unlike the marble statue, the golden mouth did not move when she spoke, as if it were only a mask for the watery creature behind it. “Besides, he is mine.”

The marble statue did not answer.

“I am?” asked the punk.

“Travis Zelley,” said the steam-wreathed apparition. “Your mother gave you sixpence to throw in my waters when you came to worship me on your seventh birthday.”

“Uh, I did?” squeaked Travis. The only waters he could remember throwing any kind of money into was on a trip to the Roman Baths, just nearby. It came back to him that his mother had given him a sixpence. He had wanted to keep it for lollies, but she made him throw it in. A real silver sixpence, it had been a few years before the

change to decimal currency and the dull 5p coins. They’d had afternoon tea in the Pump Room afterward. He hadn’t thought of it as worshipping anyone. But he suddenly remembered where he’d seen the golden face before. It was a mask on display in the museum part of the Roman Baths.

The stone woman suddenly swung Travis towards the map, throwing him at it as if it were a window. As she let go he felt a moment of elation that he would escape after all, until he found himself falling not to the pavement, but on to grass, somewhere entirely different. It was suddenly bright, so bright he had to shut his eyes for a second. Blinking them open he saw he was somewhere outdoors but surrounded by high walls. It was hot, savagely hot after the cold winter’s night he’d been in a moment before.

He started to get up but was forced down again as the stone woman suddenly appeared in front of him. She was hissing in anger. The map she still clutched in her right hand was somehow stretched into thin air as if held by some invisible person opposite her, and as he watched, it tore across the folds and one entire quarter of the map disappeared, rusty water spraying down the statue’s arm.

She turned to him, her hand making a terrible claw. She picked him up, stone fingernails ripping through skin, deep to the bone, and shook him, like a terrier with a rat.

“You have cost me more than I care to pay,” she said in that eerie, cavernous voice. “The ritual does not demand pain before death, but you shall have it.”

Travis started screaming, but there was no one to hear.

The hot waters in the Abbey Churchyard subsided as quickly as they had risen, and there was no steam, no strange figure, no golden head. The streetlights flickered and returned to life. A cold breeze came up and blew rubbish along the streets and lanes, including a piece of heavy, antique paper: the torn-off section of the marble woman’s map. It skipped and slid past the Pump Room, blown westward towards Stall Street, where it was arrested by slapping into one of the columns of the colonnade on the far side. Already wet, it stuck there until the early morning, when it was spotted by a street cleaner. She peeled it off, saw it was something unusual, and took it home. She was surprised it dried so well, the rusty water streaks leaving no mark, and greatly pleased when her brother-in-law sold it the next Wednesday from his bric-a-brac market stall in Guinea Lane for ten pounds to one of his regular customers, the bibliophile Sir Richard Wedynk.

Chapter 1

Bath, Saturday, 10th December 1983

Bees. With the Romans a flight of bees was considered a bad omen.

THE SMALL BOOKSHOP IN BATH WAS NOT, IN FACT, SMALL. IT APPEARED to be no more than a cramped and narrow shop occupying half the ground floor of a three-story Georgian terrace house, the other half given over to an equally cramped tobacconist who sold dubious pipe mixtures of her own devising and cigarettes from “East of Istanbul.” But the Small Bookshop was actually an outpost of the St. Jacques clan, so there was more to it than could be seen from outside, both above and below. Even the tobacconist half was a front, inhabited by a right-handed bookseller whose awful offerings were a ploy to limit customers and allow her to get on with her researches into the works of Izaak Walton and obscure enchantments involving fish.

The other fifteen booksellers on the permanent staff of the Small Bookshop included a dozen of the left-handed variety: field agents, enforcers, and occasional executioners. They were primarily there to keep an eye on human interactions with the entity the Romans called Sulis Minerva. She inhabited the ever-popular Roman Baths, and when given the correct gifts, properly inscribed, would grant boons of power, particularly to people seeking revenge or retribution. The Baths were visited by tens of thousands of people every year, so it was hard work for the booksellers who monitored the queue going in, keeping watch for Death Cultists and others of that ilk who came to ask Sulis Minerva for the causation of a fatal accident or an astonishingly swift mortal illness. A less careful watch was maintained outside the Bath’s opening hours, the constant surveillance replaced by occasional random patrols through the evening and night.

The bookshop was often used as a temporary repository for bulk purchases of secondhand books made in the West Country. “An Auction of the Library of a Distinguished Lady” or “Sale of the Property of a Gentleman, being mostly books” and the like. The books were sorted and cataloged there before being dispatched to the New Bookshop in London, the Mews Bookshop in York, or if they were too arcane to be sold, sent to the Crawley Tunnel Library in Edinburgh, the Salinae mine in Cheshire, or to other secretive St. Jacques establishments.

When a shipment came in from one of these purchases, more right-handed booksellers were drafted into the Small Bookshop to help triage the books before cataloging. The right-handed, while not fighters like the left-handed, were proficient in various arcane arts, including one often mistaken as purely mundane: extensive knowledge of printing, paper, bookbinding, and bookselling through the ages. A book of sorcerous interest might escape magical detection by various means, such as being bound in rune-etched bone disguised under buckram; or encased in a field of lunar misdirection by exposure to seventeen new moons in a silver bowl upon one of three particular hills in England (a procedure often spoiled by rain). These methods worked well against general spells of discovery but were of no use if a right-handed bookseller found some incongruous detail of binding, type, title, content, or provenance and looked more deeply.

Vivien St. Jacques, right-handed bookseller, had found just such a discrepancy in a volume of Thomas Moule’s maps of English counties. The gilt letters embossed on the spine declared it to be A Collection of Maps and the engraved title page went further to say it was “A Collection of Maps by Thomas Moule, Bound for Sir Richard Wedynk by Amos Carlyle of Salisbury in 1954,” which was all well and good, Moule’s maps of English counties being very nicely done and collectible and Carlyle a well-known and excellent modern bookbinder. But Vivien had noticed a slight bulge in the back of the case and some not particularly expert resewing and gluing of the leather binding, work that would not meet Carlyle’s standards, indicating it had been opened up later and something slid in against the board.

She set the volume down on the worktable and looked at it again carefully. She could feel a slight tingling in the thumb of her gloved right hand, which might or might not be related to this book. It could be a general warning, a foretelling of something bad on the horizon.

“Hmmm,” she said.

“Got something interesting?” asked Ruby from the neighboring table. She was also a right-handed bookseller, one of the few permanently stationed in the Small Bookshop. She had asked for help to assess the recent purchase of the late Sir Richard Wedynk’s library, and Vivien had come from London in answer to the call. Ruby was a decade older than Vivien, in her early thirties,

and was notionally in charge, inasmuch as anyone was, the right-handed booksellers tending to work most of the time as a kind of anarchist collective driven by shared interests and responsibilities, setting their own tasks to achieve the generally desired objectives. Though they did take direction from the senior-most, when required, and Great-Aunt Evangeline’s word was the final law.

“There’s definitely something hidden in the binding,” said Vivien. She pushed her chair back and got up, wending her way between the piles of tea chests full of books that had been stacked in lines to allow navigation, over to the essential cupboard that stood by the door to the stairs. Every workroom of the right-handed booksellers had an essential cupboard. Some had more than one. They varied in style, if not in contents. This one was originally an eighteenth-century housekeeper’s cupboard, with three individual cupboards above two ranks of drawers.

Vivien touched her white-cotton-gloved right forefinger to the third drawer on the right, which sprang open. She looked into it and frowned.

“Someone hasn’t put the dowsing rod back,” she said.

“Oh, I’ve got it,” replied Ruby. She held a Y-shaped hazel branch over her head, only the stick and her hand visible above the line of tea chests. “Sorry.”

Vivien retraced her path through the narrow way between tea chests, narrowly avoiding tearing her very new Laura Ashley white lawn blouse on a bit of jagged tin that had broken off the corner of one of the plywood boxes. Most of the younger right-handed booksellers would have preferred to pack books in cardboard boxes, but the older ones still insisted they must use the considerable stock of tea chests that perennially shifted back and forth between the various St. Jacques locations like flotsam borne upon the tide.

“Thanks,” said Vivien. She took the hazel stick, and holding it in approved dowsing fashion, returned to her own table. When she passed the rod over the book it bucked in her hand, drawn like a very powerful magnet to iron towards the slight lump in the binding. She had to use considerable strength to hold it back and then even hold her breath for a moment to add sorcerous strength in order to turn the stick aside before she let it go, and it became just a forked hazel branch again.

“Something hidden, and powerful,” said Vivien. “Can you stand by me for this one, Ruby?”

“Of course!” replied Ruby eagerly. She slid back her chair, got up, and sidled over next to Vivien. “That whole chest has been nothing but editions of Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There. Unexciting editions at that. No firsts, not even a later printing, nothing earlier than 1896.”

“Pity,” said Vivien. “I’ll get the gear.”

She returned to the essential cupboard to fetch a silver-washed straight razor, two mismatched sets of very long similarly silver-plated tongs that once might have been salad servers, and a vintage silver hatpin. Coming back in a hurry, she did tear her shirt on a tea chest corner, but paid it no attention, all her tho

ghts now on this mysterious object in the binding of the book. “The Alice fixation suggests Sir Richard had an interest in the esoteric. Was he a known practitioner or anything of that sort?”

“A fringe-dweller, most likely,” replied Ruby. She was peering at the book of maps through a jeweler’s loupe, her face close to the binding. “A good customer of the bookshop, but as far as we know not actively involved in the Old World. He was vetted in 1965 and again in 1978, cleared of associations. I don’t think he was clever enough to keep anything hidden. He must have had his suspicions, but he didn’t act upon them.”

“No connection with Sulis Minerva?” asked Vivien as she made her way back to the worktable. Ruby lifted a tea chest off a stack that was partially blocking the window, allowing more of the weak winter sunlight to come through. There was a six-bulb chandelier above, so plenty of illumination, but they both knew the sun was a better source to see things that were hidden, or if it came to that, as a protection against things inimical that prospered in the dark.

“He has never been observed entering the Baths,” she said. “If he was a real follower he couldn’t keep away. Though there are some other adits of her power, I very much doubt he frequented them. He was what he seemed, a nauseatingly rich, amiable old buffer who never worked his whole life and just collected books.”

“So, this is an anomaly,” said Vivien. “Let’s see what we’ve got.”

Taking up the straight razor, she carefully cut a slit in the leather binding at the top of the back case, then used the tongs to lift the leather up a little.

“Looks like a folded page has been slid in here,” she said. “Old paper. Older than the book.”

Her right thumb was twitching now, uncontrollably. Outside, the wintry clouds parted a little and a beam of actual, honest-to-goodness sunshine came through the window, making the previously unseen motes of dust twinkle. But it only lasted for a few seconds before the clouds closed up again and the sunshine disappeared as if turned off with a switch.

“It’s powerful,” added Vivien. “Saturated with sorcery. An entity’s, I think, not a human practitioner’s. We’d better get one of the sinisters up here.”

“I’ll call down,” replied Ruby. “I’m not sure who’s available right now. Ibrahim and Polly have gone to escort the next shipment from Sir Richard’s library, and there’s a full shift watching the Baths.”

She hurried over to the intercom mounted on the wall next to the door and pressed the orange button. It squawked for a second, then a testy woman’s voice answered.

“Yes? What?”

“Ruby here, Delphine. In the sorting room. Can you send up a leftie or two? Vivien’s found something sorcerous in one of the books.” '"

I’ll see who’s available.”

There was a hatch set in the wall between the tobacconist and the bookstore. Vivien and Ruby heard footsteps, the hatch being slid open, Delphine calling out and some indistinct reply.

“One of you layabouts is needed upstairs, in the sorting room. Yes, you’ll do. What? I don’t care if you’re not rostered on. Up you go.”

The footsteps came closer, then Delphine’s cigarette-rasped voice issued a curt, “Done.”

The intercom clicked off.

“Any preliminary ideas?” asked Ruby, returning to the worktable. They both stared at the book, which was facedown, the slit in the back binding towards them.

“Not yet,” replied Vivien. She took up the long tweezers in her right hand and closed and opened them a few times, the points clicking. Ruby held her own right hand six inches above the book, palm down, and inhaled deeply.

Ruby exhaled.

“You’re right about the sorcery. But I’m not sure you’re correct about it being an entity’s magic. I’d say it was a joint effort, some mortal practitioner drawing the map and providing the focus, an Old One supplying the power. Not an entity I know. Something old and cold and hard.”

Vivien nodded. She tilted her head, listening to the sound of someone coming up the stairs, taking them very swiftly, leaping up three or four or even five at a time, in heavy shoes or boots.

“Our left-handed helper comes,” said Ruby drily.

“Hmmm,” said Vivien. There was something familiar about the style of the stair ascent, a wholly unnecessary rapidity and joie de vivre in simply trying to leap as many steps as possible in one go. So while she was not expecting this particular left-handed bookseller, she was not surprised when the door was flung open to reveal an exceptionally stylish young woman, albeit one exceptionally stylish for circa 1816.

This stunning apparition wore a fox fur tippet over a high-waisted morning dress of pale-blue Italian taffeta with golden ribbons at the neck and wrists, a single white kid leather glove on the left hand, and a straw hat also beribboned in gold, atop a lace coif. The ensemble’s historical accuracy was somewhat spoiled by the addition of a surprisingly large carpetbag and the toes of black Dr. Marten boots peeking out from under the almost floor-length dress.

Thanks to their somewhat “shape-shiftery nature,” the booksellers could and did change gender from time to time, but at present, this Regency arrival was male, and was in fact Vivien’s younger brother, Merlin. He simply liked clothes of all kinds, and let his fancy take him where it would. Vivien was physically very similar, and obviously his sister, but she lacked whatever it was that made (nearly) all eyes look first to Merlin, and Vivien preferred it that way.

“When in Bath,” said Merlin, interpreting Ruby’s enquiring look at his clothes. “I made four pounds fifty posing for photographs with American tourists on the way up from Manvers Street. If I’d

brought a Polaroid camera I could retire after a few days, I’d say they’d be good for two pounds a pic, at least. Surprised there’s still so many around at this time of year. Tourists, I mean.”

“They come for Christmas and hope for snow,” said Ruby. “They might get it this year.”

“Are you Jane or one of her characters?” asked Vivien. “And where did you get that dress?”

“I’m Elizabeth Bennet, of course,” said Merlin. “The dress is from the BBC, the miniseries Pride and Prejudice from a few years back. You know, with Elizabeth Garvie. I’ve made friends with one of the wardrobe department assistants. This was Garvie’s dress halfway through episode two.”

“That carpetbag is much too big and ahistorical,” said Ruby. “Should be a reticule.”

“I know,” replied Merlin with a shrug. “But those tourists don’t, or they don’t care. Besides, a reticule would be far too small.”

He set the bag down on the end of the table and opened it. Shrugging off the tippet, he folded it carefully and tucked it in one end of the bag that contained, among other things, his favored .357 Magnum Smython and two speedloaders; a turned lignum vitae truncheon from William IV’s time, marked with the royal arms; a parrying dagger reputed to have belonged to Sir Philip Sidney, the blade later plated with silver; his current reading material, a Penguin paperback of Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons, the 1977 edition with the generally scorned cover; a day-old Chelsea bun wrapped in waxed paper; two wire coat hangers; and a variety of other small useful odds and ends.

“Why are you in Bath?” asked Vivien. “I thought you had the weekend off.”

“I do, or did,” replied Merlin. He hesitated, then added, “Susan’s visiting her mother. I thought I might pop over and see her later.”

Merlin and Vivien had met Susan Arkshaw earlier in the year, and they’d been involved with her in deep matters that led to the binding of a powerful and malevolent entity, the unmasking of a traitor among the booksellers, and the discovery that Susan’s father was the Old Man of Coniston. An Ancient Sovereign, as the most powerful entities of the Old World were known. All three had become friends, and Merlin and Susan more, though their relationship had recently run into stormy waters. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...