- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

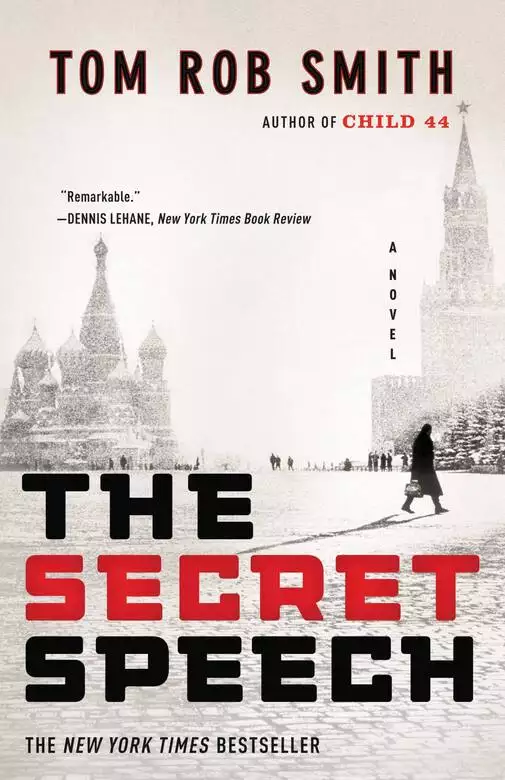

Synopsis

Soviet Union, 1956. Stalin is dead, and a violent regime is beginning to fracture. A secret speech composed by Stalin's successor Khrushchev is distributed to the entire nation. Its message: Stalin was a tyrant. Its promise: The Soviet Union will change.

Facing his own personal turmoil, former state security officer Leo Demidov is also struggling to change. The two young girls he and his wife, Raisa, adopted have yet to forgive him for his part in the death of their parents. They are not alone. Now that the truth is out, Leo, Raisa, and their family are in grave danger from someone consumed by the dark legacy of Leo's past career.

From the streets of Moscow, to the Siberian gulags, and to the center of the Hungarian uprising in Budapest, The Secret Speech is an epic audiobook that confirms Tom Rob Smith as one of the most exciting new authors writing today.

From the Compact Disc edition.

Release date: May 3, 2010

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Secret Speech

Tom Rob Smith

3 JUNE 1949

DURING THE GREAT PATRIOTIC WAR he’d demolished the bridge at Kalach in defense of Stalingrad, rigged factories with dynamite, reducing them to rubble, and

set indefensible refineries ablaze, dicing the skyline with columns of burning oil. Anything that might have been requisitioned

by the invading Wehrmacht he’d rushed to destroy. While his fellow countrymen wept as hometowns crumbled around them, he’d

surveyed the devastation with grim satisfaction. The enemy would conquer a wasteland, burnt earth and a smoke-filled sky.

Often improvising with whatever materials were at hand—tank shells, glass bottles, siphoning gasoline from abandoned, upturned

military trucks—he’d gained a reputation for being a man the State could rely on. He never lost his nerve, never made a mistake

even when operating in extreme conditions: freezing winter nights, waist deep in fast-flowing rivers, his position coming

under enemy fire. For a man of his experience and temperament, today’s job should be routine. There was no urgency, no bullets

whistling overhead. Yet his hands, renowned as the steadiest in the trade, were trembling. Drops of sweat rolled into his

eyes, forcing him to dab them with the corner of his shirt. He felt sick, a novice again, as this was the first time that

fifty-year-old war hero Jekabs Duvakin had ever blown up a church.

There was one more charge to be set, directly before him, positioned in the sanctuary where the altar had once stood. The

bishop’s throne, icons, menalia—everything had been removed. Even the gold leaf had been scraped from the walls. The church

stood empty except for the dynamite dug into the foundations and strapped to the supporting columns. Pillaged and picked clean,

it remained a vast and awesome space. The central dome, mounted with a crown of stained-glass windows, was so tall and filled

with so much daylight that it seemed as if it were part of the sky. Head arched back, mouth open, Jekabs admired the dome’s

peak some fifty meters above him. Rays of sunlight entered through the high windows, illuminating frescoes that were soon

to be blasted apart, broken down into their constituent parts: a million specks of paint. The light spread across the smooth

stone floor not far from where he sat as if trying to reach out to him, an outstretched golden palm.

He muttered:

—There is no god.

He said it again, louder this time, the words echoing inside the dome:

—There is no god!

It was a summer’s day; of course there was light. It wasn’t a sign of anything. It wasn’t divine. The light meant nothing.

He was thinking too much, that was the problem. He didn’t even believe in God. He tried to recall the State’s many antireligious

phrases.

Religion belonged in an age where every man was for himself And God was for every man.

This building wasn’t sacred or blessed. He should see it as nothing more than stone, glass, and timber—dimensions one hundred

meters long and sixty meters wide. Producing nothing, serving no quantifiable function, the church was an archaic structure,

erected for archaic reasons by a society that no longer existed.

Jekabs sat back, running his hand along the cool stone floor smoothed by the feet of many hundreds and thousands of worshippers

who’d been attending services for many hundreds of years. Overwhelmed by the magnitude of what he was about to do, he began

to choke as surely as if there was something stuck in his throat. The sensation passed. He was tired and overworked—that was

all. Normally on a demolition project of this scale he’d be assisted by a team, the workload shared. In this instance he’d

decided his men could play a peripheral role. There was no need to divide the responsibility, no need to involve his colleagues

unnecessarily. Not all of them were as clear-thinking as he was. Not all of them had purged themselves of religious sentiments.

He didn’t want men with conflicted motivation working alongside him.

For five days, starting at sunrise, finishing at sunset, he’d laid every charge—explosives strategically positioned to ensure

the structure collapsed inwards, the domes falling neatly on top of themselves. Far from demolition being chaotic, there was

order and precision to his craft and he was proud of his particular skill. This building presented a unique challenge. It

wasn’t a moral question but an intellectual test. With a bell tower and five golden cupolas, the largest of which was supported

on a tabernacle eighty meters high, today’s controlled, successful demolition would be a fitting conclusion to his career.

After this, he’d been promised an early retirement. There’d even been talk about him receiving the Order of Lenin, payment

for a job no one else wanted to do.

He shook his head. He shouldn’t be here. He shouldn’t be doing this. He should’ve feigned sickness. He should’ve forced someone

else to lay the final charge. This was no job for a hero. But the dangers of avoiding work were far greater, far more real

than some superstitious notion that this work might be cursed. He had his family to protect—a wife, a daughter—and he loved

them very much.

LAZAR STOOD AMONG THE CROWD, held back from the perimeter of the Church of Sancta Sophia at a precautionary distance of a hundred meters, his solemnity

contrasting with the excitement and chatter of those around him. He decided that they were the kind of crowd that might have

attended a public execution, not out of principle, but just for the spectacle, just for something to do. There was a festive

atmosphere, conversations bubbling with anticipation. Children bounced on their fathers’ shoulders, impatient for something

to happen. A church was not enough for them: the church needed to collapse for them to be entertained.

At the front of the barricade on a specially constructed podium to provide elevation, a film crew were busy setting up tripods

and cameras—discussing which angles to best capture the demolition. Particular attention was paid to ensure they caught all

five cupolas, and there was earnest speculation as to whether the timber domes would smash in the air as they crashed into

each other or not until they hit the ground. It would depend, they reasoned, on the skill of the experts laying the dynamite

inside.

Lazar wondered if there could be sadness too among the crowd. He looked left and right, searching for like-minded souls—the

married couple in the distance, both of them silent, their faces drained of color, the elderly woman at the back, her hand

in her pocket. She had some item hidden in there, a crucifix perhaps. Lazar wanted to divide this crowd, to separate the mourners

from the revelers. He wanted to stand beside those who appreciated what was about to be lost: a three-hundred-year-old church.

Named and designed after the Cathedral of Sancta Sophia in Gorky, it had survived civil wars, world wars. The recent bomb

damage was a reason to preserve, not to destroy. Lazar had contemptuously read the article published in Pravda claiming structural instability. Such a claim was nothing more than a pretext, a spoonful of false logic to make the deed palatable. The State had ordered

the church’s destruction, and what was worse, far worse, was that the order had been made in agreement with the Orthodox Church.

Both parties to this crime claimed it was a pragmatic decision, not an ideological one. They’d listed a series of contributing

factors: damage by Luftwaffe raids. The interior required elaborate renovations that couldn’t be paid for. Furthermore, the

land in the heart of the city was needed for a crucial construction project. Everyone in a position of power was in agreement.

This church, hardly one of Moscow’s finest, should be torn down.

Cowardice lay behind the shameful arrangement. The ecclesiastical authorities, having rallied every church congregation behind

Stalin during the war, were now an instrument of the State, a ministry of the Kremlin. This demolition was a demonstration

of that subjugation. They were blowing it up for no reason other than to prove their humility: an act of self-mutilation to

testify that religion was harmless, docile, tamed. It didn’t need to be persecuted anymore. Lazar understood the politics

of sacrifice: wasn’t it better to lose one church than to lose them all? As a young man he’d witnessed theological seminaries

turned into workers’ barracks, churches turned into antireligious exhibition halls. Icons had been used as firewood, priests

imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Continued persecution or thoughtless subservience: that had been the choice.

JEKABS LISTENED TO THE SOUND of the crowd gathered outside, the bustle as they waited for the show to begin. He was late. He should’ve finished by now.

Yet for the past five minutes he hadn’t moved, staring down at the final charge and doing nothing. Behind him, he heard the

creak of the door. He glanced over his shoulder. It was his colleague and friend, standing at the doorway, on the threshold,

as if fearful of entering. He called out, his voice echoing:

—Jekabs! What’s wrong?

Jekabs replied:

—I’m almost done.

His friend hesitated before remarking, softening his voice:

—We will drink tonight, the two of us, to celebrate your retirement? In the morning you’ll have a terrible headache, but by

the evening you will feel much better.

Jekabs smiled at his friend’s attempt at consolation. The guilt would be nothing worse than a hangover. It would pass.

—Give me five minutes.

With that, his friend left him alone.

Kneeling in a parody of prayer, sweat streaming, his fingers slippery, he wiped his face, but it made no difference, his shirt

was soaked and could absorb no more. Finish the job! And he’d never have to work again. Tomorrow he’d take his little daughter for a walk by the river. The day after he’d buy

her something, watch her smile. By the end of next week he would’ve forgotten about this church, about the five golden domes

and the sensation of the cold stone floor.

Finish the job!

He snatched hold of the blasting cap, crouched down to the dynamite.

STAINED GLASS SHOT OUT from all around the church, every window shattering simultaneously—the air filling with colored fragments. The back wall

transformed from a solid mass to a rushing dust cloud. Ragged chunks of stone arced up then crashed to the ground, chewing

up the grass, skidding toward the crowd. The flimsy barrier offered no protection, swatted aside with a shrill clang. To Lazar’s

right and left people dropped as their legs were knocked out from under them. Children on their fathers’ shoulders clutched

their faces, sliced by whistling stone and glass shards. As though it were a single entity, a great shoal, the crowd pulled

away in unison, crouching, hiding behind each other, fearful that more debris would rip through them. No one had been expecting

anything to happen yet; many hadn’t even been looking in the right direction. The film cameras weren’t set up. There were

workers within the blast perimeter, a perimeter hopelessly underestimated or an explosion misjudged.

Lazar stood, his ears ringing, staring at the plumes of dust, waiting for it to settle. As the cloud thinned it revealed a

hole in the wall twice the height of a man and equally wide. The damage made it appear as if a giant had accidentally put

the tip of his boot through the church and then apologetically retracted his foot, sparing the rest of the building. Lazar

looked up at the golden domes. Everyone around him followed suit, a single question on everyone’s mind: would the towers fall?

Out of the corner of his eye Lazar could see the film crew scrambling to get the cameras rolling, wiping the dust off the

lens, abandoning the tripods, desperate to capture the footage. If they missed the collapse, no matter what the excuse, their

lives would be on the line. Despite the danger, no one ran away, they remained fixed to the spot, searching for even the slightest

movement, a tilt or jolt—a tremble. It seemed as if even the injured were silent in anticipation.

The five domes did not fall, aloof from the petty chaos of the world below. While the church remained standing, scores in

the crowd were bleeding, wounded, weeping. As surely as if the sky had clouded over, Lazar sensed the mood change. Doubts

surfaced. Had some unearthly power intervened and stopped this crime? Spectators began to leave, a few slowly, then others

joined them, more and more, hurrying away. No one wanted to watch anymore. Lazar struggled to suppress a laugh. The crowd

had broken apart while the church had survived! He turned to the married couple, hoping to share this moment with them.

The man standing directly behind Lazar was so close they were almost touching. Lazar hadn’t heard him approach. He was smiling

but his eyes were cold. He didn’t wear a uniform or show his identity card. However, there was no question that he was State

Security, a secret police officer, an agent of the MGB—a deduction possible not through what was present in his appearance

but what was absent. To the right and left there were injured people. Yet this man had no interest in them. He’d been planted

in the crowd to monitor people’s reactions. And Lazar had failed: he’d been sad when he should’ve been happy and happy when

he should’ve been sad.

The man spoke through a thin smile, his dead eyes never moving from Lazar:

—A small setback, an accident, easily fixed. You should stay: perhaps it will still happen today, the demolition. You want

to stay, don’t you? You want to see the church fall? It will be quite spectacular.

—Yes.

A careful answer and also the truth, he did want to stay, but no, he didn’t want the church to fall and he certainly wouldn’t

say so. The man continued:

—This site is going to become one of the largest indoor swimming pools in the world. So our children can be healthy. It is

a good thing, our children being healthy. What is your name?

The most ordinary of questions and yet the most terrifying:

—My name is Lazar.

—What is your occupation?

No longer masquerading as casual conversation, it was now an open interrogation. Subjugation or persecution, being pragmatic

or principled—Lazar had to choose. And he did have a choice, unlike many of his brethren who were instantly recognizable.

He didn’t have to admit that he was a priest. Vladimir Lvov, former chief procurator of the Holy Synod, had argued that priests

need not set themselves apart by their dress and that they may throw off their cassocks, cut their hair, and be changed into ordinary mortals. Lazar agreed. With his trim beard and unremarkable appearance, he could lie to this agent. He could disown his vocation and

hope that the lie would protect him. He worked in a shoe factory or he crafted tables—anything but the truth. The agent was

waiting.

IN THEIR FIRST WEEKS TOGETHER Anisya hadn’t given the matter much thought. Maxim was only twenty-four years old, a graduate of Moscow’s Theological Academy

Seminary, closed since 1918 and recently reopened as part of the rehabilitation of religious institutions. She was older than

him by six years, married, unattainable, a tantalizing prospect for a young man whom she supposed to have limited, if any,

sexual experience. Introspective and shy, Maxim never socialized outside of the church and had few friends or family, at least

none that lived in the city. It was unsurprising that he’d developed something of an infatuation. She’d tolerated his lingering

stares, perhaps even been flattered by them. But in no way had she encouraged him. He’d misunderstood her silence, inferring

permission to continue courting her. It was for that reason that he now felt confident enough to take hold of her hand and

say:

—Leave him. Live with me.

She’d been convinced he’d never find the courage to act upon what could only ever be a childish daydream—the two of them running

off together. She’d been wrong.

Remarkably, he’d chosen her husband’s church to cross the line from private fantasy into open proposition: the frescoes of

disciples, demons, prophets, and angels judged their illicit moves from the shadowy alcoves. Maxim was risking everything

he’d trained for, facing certain disgrace and exile from the religious community with no hope of redemption. His earnest,

heartfelt plea was so misjudged and absurd that she couldn’t help but react in the worst possible way. She uttered a short,

surprised laugh.

Before he had time to reply the heavy oak door slammed shut. Startled, Anisya turned to see her husband—Lazar—hurrying toward

them with such urgency that she could only presume that he’d misconstrued the scene as evidence of her infidelity. She pulled

away from Maxim, a sudden movement that only compounded the impression of guilt. But as he drew closer she realized that Lazar,

her husband of ten years, was preoccupied with something else. Breathless, he took hold of her hands, hands which only seconds

ago had been held by Maxim:

—I was picked out of the crowd. An agent questioned me.

He spoke rapidly, the words tumbling out, their importance brushing aside Maxim’s proposal. She asked:

—Were you followed?

He nodded:

—I hid in Natasha Niurina’s apartment.

—What happened?

—He remained outside. I was forced to leave through the back.

—Will they arrest Natasha and question her?

Lazar raised his hands to his face:

—I panicked. I didn’t know where else to go. I shouldn’t have gone to her.

Anisya took him by the shoulders:

—If the only way they can find us is by arresting Natasha, we have a little time.

Lazar shook his head:

—I told him my name.

She understood. He wouldn’t lie. He wouldn’t compromise his principles, not for her, not for anyone. Principles were more

important than their lives. He shouldn’t have attended the demolition: she’d warned him it was an unnecessary risk. The crowd

was inevitably going to be monitored and he’d be a conspicuous observer. He’d ignored her, as was his way, always appearing

to contemplate her advice but never heeding it. Hadn’t she pleaded with him not to alienate the ecclesiastical authorities?

Were they in such a position of strength that they could afford to make enemies of both the State and the Church? But he had

no interest in the politics of alliance: he only wanted to speak his mind even if it left him isolated, openly criticizing

the new relationship between bishops and politicians. Stubborn, headstrong, he demanded that she support his stance while

giving her no say in it. She admired him, a man of integrity. But he did not admire her. She was younger than him and had

only been twenty years old when they’d married. He’d been thirty-five. At times she wondered whether he’d married her because

being a White Priest, a married priest, taking a monastic vow, was itself a reformist statement. The concept appealed to him,

fitting with his liberal, philosophical scheme. She’d always been braced for the moment when the State might cut across their

lives. However, now that the moment had come, she felt cheated. She was paying for his opinions, opinions that she’d never

been allowed to influence or contribute to.

Lazar put a hand on Maxim’s shoulder:

—It would be better if you returned to the theological seminar and denounced us. Since we’re going to be arrested the denunciation

would only serve to distance you from us. Maxim, you’re a young man. No one will think worse of you for leaving.

Coming from Lazar, the offer to run was a loaded proposition. Lazar considered such pragmatic behavior beneath him, suitable

for others, weaker men and women. His moral superiority was stifling. Far from offering Maxim a way out, it trapped him.

Anisya interjected, trying to keep her voice friendly:

—Maxim, you must go.

He reacted sharply:

—I want to stay.

Slighted by her earlier laugh, he was stubborn and indignant. Speaking in a double meaning invisible to her husband, she said:

—Please Maxim, forget everything that has happened, you will achieve nothing by staying.

Maxim shook his head:

—I’ve made my decision.

Anisya noticed Lazar smile. There was no doubt her husband was fond of Maxim. He’d taken him under his wing, blind to his

protégé’s infatuation with her, alert only to the deficiencies in his knowledge of scripture and philosophy. He was pleased

with Maxim’s decision to stay, believing that it had something to do with him. Anisya moved closer to Lazar:

—We cannot allow him risk to his life.

—We cannot force him to leave.

—Lazar, this is not his fight.

It was not her fight either.

—He has made it his. I respect that. You must too.

—It is senseless!

In modeling Maxim on himself, the martyr, her husband had chosen to humiliate her and condemn him. Lazar exclaimed:

—Enough! We don’t have time! You wish him to be safe. I do too. But if Maxim wants to stay, he stays.

LAZAR HURRIED TOWARD THE STONE ALTAR, hastily stripping it bare. Every person connected to his church was in danger. He could do little for his wife or Maxim:

they were too closely connected to him. But his congregation, the people who’d confided in him, shared their fears—it was

essential their names remain a secret.

With the altar bare, Lazar gripped the side:

—Push!

None the wiser but obedient, Maxim pushed the altar, straining at the weight. The rough stone base scratched across the stone

floor, slowly sliding aside and revealing a hole, a hiding place created some twenty years ago during the most intensive attacks

on the church. The stone slabs had been removed, exposing earth that had been carefully dug and lined with timber supports

to stop it subsiding, creating a space one meter deep, two meters wide. It contained a steel trunk. Lazar reached down and

Maxim followed suit, taking the opposite end of the trunk and lifting it out, placing it on the floor, ready to be opened.

Anisya lifted the lid. Maxim crouched beside her, unable to keep the amazement out of his voice:

—Music?

The trunk was filled with handwritten musical scores. Lazar explained:

—The composer attended services here, a young man—not much older than you, a student at the Moscow Conservatory. He came to

us one night, terrified that he was about to be arrested. Fearing that his work would be destroyed, he entrusted us with his

compositions. Much of his work had been condemned as anti-Soviet.

—Why?

—I don’t know. He didn’t know either. He had nowhere to turn, no family or friends he could trust. So he came to us. We agreed

to take possession of his life’s work. Shortly afterward, he disappeared.

Maxim glanced over the notes:

—The music… is it good?

—We haven’t heard it performed. We dare not show it to anyone, or have it played for us. Questions might be asked.

—You have no idea what it sounds like?

—I can’t read music. Neither can my wife. But Maxim, you’re missing the point. My promise of help wasn’t dependent on the

merits of his work.

—You’re risking your lives? If it’s worthless…

Lazar corrected him:

—We’re not protecting these papers; we’re protecting their right to survive.

Anisya found her husband’s assuredness infuriating. The young composer in question had come to her, not him. She’d then petitioned

Lazar and convinced him to take the music. In the retelling of the story he’d smoothed over his doubts, anxieties—reducing

her to nothing more than his passive supporter. She wondered if he was even aware of the adjustments he’d made to the history,

automatically elevating his own importance, recentering the story around him.

Lazar picked up the entire collection of unbound sheet music, maybe two hundred pages in total. Included among the music were

documents relating to the business of the church and several original icons that had been hidden, replaced with reproductions.

He hastily divided the contents into three piles, checking as best he could that complete musical compositions were kept together.

The plan was to each smuggle out a more or less equal share. Divided in three, there was a reasonable chance some of the music

would survive. The difficulty was finding three separate hiding places, three people who’d be prepared to sacrifice their

lives for notes on a page even though they’d never met the composer or heard his music. Lazar knew many in his parish would

help. Many were also likely to be under suspicion of some kind. For this task they needed the help of a perfect Soviet, someone

whose apartment would never be searched. Such a person, if they existed, would never help them.

Anisya threw out suggestions:

—Martemian Syrtsov.

—Too talkative.

—Artiom Nakhaev.

—He’d agree, take the papers and then panic, lose his nerve, and burn them.

—Niura Dmitrieva.

—She’d say yes but she’d hate us for asking. She wouldn’t sleep. She wouldn’t eat.

In the end, two names—that’s all they could agree upon. Lazar decided to keep one portion of the music hidden in the church,

along with the larger icons, returning them to the trunk and pushing the altar back into position. Since Lazar was the most

likely to be followed, Anisya and Maxim were to carry their share of the music to the two addresses. They would leave separately.

Anisya was ready:

—I’ll go first.

Maxim shook his head:

—No. I will.

She guessed his reason for offering: if Maxim got away then the chances were that she would too.

They unlocked the main door, lifting up the thick timber beam. Anisya sensed Maxim hesitate, no doubt afraid, the danger of

his predicament finally sinking in. Lazar shook his hand. Over her husband’s shoulder, Maxim looked at her. Once Lazar was

done, Maxim stepped toward her. She gave him a hug and watched him set off into the night.

Lazar closed the door, locking it behind him, reiterating the plan:

—We wait ten minutes.

Alone with her husband, she stood near the front of the church. He joined her. To her surprise, rather than praying, he took

hold of her hand.

TEN MINUTES HAD PASSED, they moved to the door. Lazar lifted the beam. The papers were in a bag, slung over her shoulder. Anisya stepped outside.

They’d already said good-bye. She turned, watching in silence as Lazar shut the door behind her. She heard the beam lowered

back in place. Walking toward the street, she checked for faces at the windows, movement in the shadows. Suddenly a hand gripped

her wrist. Startled, she spun around.

—Maxim?

What was he doing here? Where was the music he was carrying? From behind the back of the church a voice called out, harsh

and impatient:

—Leo?

Anisya saw a man dressed in a dark uniform—an MGB agent. There were more men behind him, clustering like cockroaches. Her

questions melted away, concentrating on the name called out: Leo. With the tug of a single word the knot of lies unraveled. That was why he had no friends or family in the city, that was

why he was so quiet in lessons with Lazar, he knew nothing of scripture or philosophy. That was why he’d wanted to leave the

church first, not for her protection but to alert the surveillance, to prepare for their arrest. He was a Chekist, a secret

police officer. He’d tricked her and her husband. He’d infiltrated their lives in order to gather as much information as possible,

not just on them but on the people who sympathized with them, dealing a blow against the remaining pockets of resistance within

the Church. Had attempting to seduce her been an objective handed down by his superiors? Had they identified her as weak,

gullible and instructed this handsome officer to form a persona

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...