- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Åsa Larsson’s first novel, The Savage Altar, was awarded the Swedish Crime Writers' Association prize for best debut. Its sequel, The Blood Spilt, was chosen as Best Swedish Crime Novel. “Among the current batch of Nordic writers, the new Larsson is one to be followed with the most minute attention,” said the Independent.

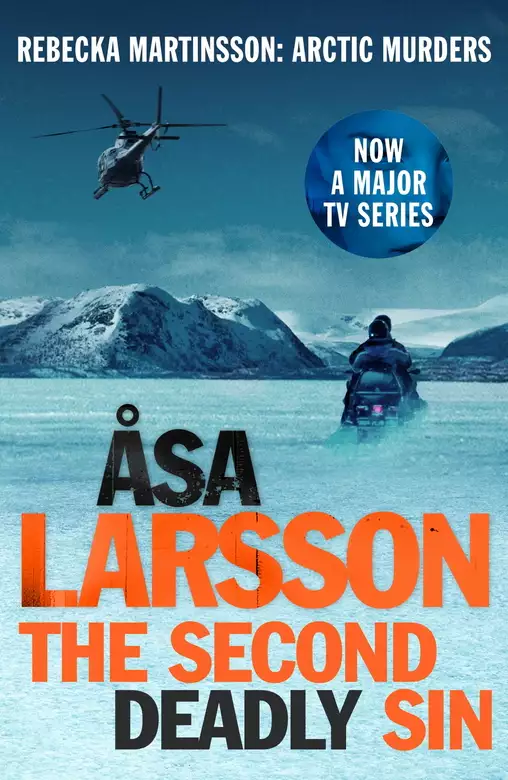

In The Second Deadly Sin, dawn breaks in a forest in northern Sweden. Villagers gather to dispatch a rampaging bear. When the beast is brought to ground they are horrified to find the remains of a human hand inside its stomach. In nearby Kiruna, a woman is found murdered in her bed, her body a patchwork of vicious wounds, the word WHORE scrawled across the wall. Her grandson Marcus, already an orphan, is nowhere to be seen. Grasping for clues, Rebecka Martinsson begins to delve into the victim’s tragic family history. But with doubts over her mental health still lingering, she is ousted from the case by an arrogant and ambitious young prosecutor. Before long a chance lead draws Martinsson back into the thick of the action and her legendary courage is put to the test once more.

Release date: September 1, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Second Deadly Sin

Åsa Larsson

He is in his kitchen, making a sandwich. His Norwegian elk-hound is on a running leash in the back yard. The calm before the storm.

Then the dog starts barking. Loud and angry at first.

What is it barking at? Certainly not a squirrel. Johansson recognises the way his dog barks at a squirrel. Surely not an elk? No, elk barks are less strident, more substantial.

Then something happens. The dog screams. Shrieks as if the gates of hell have just opened up before it. It is a sound that fills Johansson with cold terror.

And then silence.

*

Johansson races outside. No jacket. No shoes. No clear thoughts.

He stumbles his way through the autumnal darkness, towards the garage and the dog kennel.

And there, in the light from the lamp over the garage door, stands the bear. It is tugging at the dog’s body, trying to drag it away, but the dead dog is still attached to the leash. The bear turns its bloodstained jaws towards Johansson and roars at him.

Samuel steps back somewhat unsteadily. Then he summons up superhuman strength and runs faster than he has ever run before, back to the house to fetch his gun. The bear stands its ground. Nevertheless, Johansson seems to feel the beast’s hot breath on the back of his neck.

He loads the rifle with his wet hands before cautiously opening the door. He must keep calm and shoot accurately. Otherwise it could be all over in a flash. A wounded bear would take less than a second to pounce.

He creeps through the darkness. One step at a time. The hairs on the back of his head are sticking out like nails.

The bear is still there. Gobbling down what is left of the dog. When Johansson cocks the gun, it looks up.

Johansson has never trembled so much. There’s no time to lose now. He tries to stand still, but it is impossible.

The bear shakes its head threateningly. Snarls. Huffs and puffs like a pair of bellows. Then it takes a deliberate step forward. That is when Samuel shoots. There is an explosive blast. The bear falls. But quickly it stands up again. And disappears into the darkness.

*

It has vanished now into the pitch-black forest. The light over the garage door is no help at all.

Johansson walks backwards to the house, aiming the gun left and right as he does so. Ears pricked, listening for sounds from the forest. That bloody bear might come bounding towards him at any moment. He can only see for a few metres.

Twenty paces back to the door. His heart is pounding. Five. Three. He’s inside.

He’s shuddering now. His whole body is shaking. He has to put his mobile down on the table and hold onto his right hand with his left in order to push the right numbers. The leader of the local hunters responds after only one ring. They agree to meet at first light. There’s nothing they can do in the dark.

*

As dawn breaks all the men from the village gather outside Johansson’s house. It is -2°C. Tree branches white with frost. Leaves have fallen. Rowan berries gleam rust-red among the grey. Something feathery is floating through the air – the kind of snow that never settles.

They stare at the devastation in and around the dog kennel. More or less all that is left, attached to the running leash, is the dog’s skull. The rest is blood-soaked slush.

It is a hard-boiled collection of men. They are all wearing checked shirts, trousers with lots of pockets, belts carrying knives, and green jackets. The young ones have beards and a peaked cap on their heads. The older ones are clean-shaven and wear fur hats with ear flaps. These are men who make their own motorised carts for dragging back home the elks they have shot. Men who prefer cars with carburettors, so that they can mess around with the engines themselves and are not dependent on service garages where they nowadays just attach computer cables to the cars.

“This is what happened,” the hunt leader says, as the more gnarled members of his team stuff new wads of chewing tobacco into their mouths and glance furtively at Johansson, who is having difficulty in controlling the tics in various parts of his face. “Samuel heard the dog howling. He grabbed his gun and went out. We’ve had bears prowling around here for quite some time now, so he realised that might be the problem.”

Johansson nods.

“Anyway. You go out with your rifle. The bear is gobbling away at the dog, and turns to attack you. You shoot it in self-defence. It was coming towards you. You didn’t go in and fetch your gun, you had it with you from the start. No messing about in this case. Nobody’s going to be prosecuted for breaking hunting laws, right? I rang the police last night and put them in the picture. They had no hesitation in classifying it as self-defence.”

“Who’s going to hunt it down?” somebody wonders aloud.

“Patrik Mäkitalo.”

That piece of information is followed by total silence while all present consider the implications. Mäkitalo comes from Luleå. It would have been good if somebody from their own local hunting team had been commissioned to track down the bear. But none of them has a dog as proficient as Mäkitalo’s. And deep down they wonder if they are proficient enough themselves as well.

The bear is wounded. And so highly dangerous. It is essential to have a dog that dares to hold the bear at bay, rather than panicking and running back to its master with the ferocious beast hard on its heels.

And the hunter must not get cold feet either; when Teddy comes crashing through the undergrowth he might have no more than a second in which to react. The lethal target area on a bear is no wider than the base of a saucepan. And the hunter is aiming without a rifle support. It’s like shooting a flying tennis ball. If he misses it is by no means sure that he will get a second chance. Hunting bears is not something for anybody with shaky hands.

“Speak of the devil,” the hunt leader says, looking along the road.

*

Patrik Mäkitalo gets out of his car and greets the assembled group with a nod. He is about thirty-five. He tends to screw up his eyes; his beard is long and narrow, like a goat’s. A Norrbotten Mongol warrior.

Mäkitalo doesn’t say much, but listens intently to the hunt leader and asks Johansson about the shot. Where exactly was he standing? Where was the bear? What ammunition did he use?

“Oryx.”

“Good,” Mäkitalo says. “A high residual weight. With a bit of luck it might have gone right through the beast. That would make it bleed more, and make it easier to track.”

“What do you use?”

It is one of the older hunters who plucks up the courage to ask.

“Vulkan. It usually stops just inside the skin.”

Of course, the old-timers think. He doesn’t shoot to wound a bear. Killing it outright means he doesn’t need to track it down. And he’s keen to preserve the bearskin in good condition.

Mäkitalo cocks his rifle and disappears into the trees. He returns after only a minute or so, with blood on his fingers.

He opens the tailgate. His hunting dogs are in a cage, their tongues dangling out of broad doggy smiles. They have eyes for nobody but their master.

Mäkitalo asks to see a map. The hunt leader fetches one from his car. They spread it out on the bonnet.

“This no doubt shows the route it took,” Mäkitalo says. “But it’s heading into the wind, through newly planted woodland, so there’s a risk it might have veered off over here somewhere.”

He points to the beck that flows down into the River Lainio.

“Especially if it’s a mature varmint that’s learnt how to outwit dogs. You’d better make arrangements for a boat that could come to meet us, if necessary. My dogs aren’t afraid of getting their feet wet, but their master isn’t as hardy as they are.”

Everybody summons up a smile, signalling their empathy for the task ahead.

The hunt leader gets down to practicalities and asks, “Do you want to take somebody with you?”

“No. We’ll follow the trail and see where it leads us. If it takes us over here and towards the marshes, it would help if you could go and stand guard here and there.” He gestures at the map. “But let’s get some idea first of where it’s gone.”

“He ought to be easy enough to find, if he’s bleeding,” one of the men says.

Mäkitalo doesn’t even condescend to look at him when he replies: “I dunno about that; they often stop bleeding after a while and then they hide away in the thick undergrowth and tend to double back and creep up on whoever is following them. So if I’m unlucky it could be him who finds me.”

“Too bloody right,” the hunt leader says, giving the colleague who spoke out of turn a withering look.

*

Mäkitalo sets his dogs loose. They disappear up the hill like two brown streaks, sniffing at the ground. He follows them, G.P.S. device in hand.

Full steam ahead. He looks up at the sky and hopes it will not start snowing in earnest.

He is making rapid progress. He thinks briefly about the hunters he has just met. The type that sit around boozing and snoozing when they’re supposed to be on the lookout. They would never be able to move as quickly as he does. Never mind track down the prey.

He crosses the dirt track. On the other side is a sandy slope. The bear seems to have run straight up it, legs wide apart, making heavy weather of it. He puts his hand in the obvious footprints.

The people in Lainio are already on edge. They know the bear has been around now and again. Dung next to an overturned rubbish bin, steaming in the cold morning air, as red as a mushy porridge of blueberries and lingon. There’s been a lot of bear talk. Old stories have been dusted down.

Mäkitalo examines the clawmarks in the ground where it has dug its paws deep in order to thrust itself up the hill. It must have a claw the size of a knife in each toe. The villagers have measured the prints, placed matchboxes beside them and taken pictures with their mobiles.

Women and children have been kept indoors. Nobody has dared to venture out into the wood to gather berries. Parents collect their children by car from the school bus stop.

It must be a pretty big varmint, Mäkitalo thinks as he examines the tracks. An old carnivore. That’s no doubt why it took the dog.

Now he comes to a pine forest. It’s flat and the going is easy. The pines are tall, widely spaced, a colonnade, straight trunks, no branches, the wind sighing in the crowns high above. The moss that usually crackles underfoot in the summer is damp, soft and silent.

Good, he thinks. Nice and quiet.

He crosses an old boggy meadow. In the middle is an ancient barn that has collapsed. The rotten remains of the roof are scattered around the skeleton. It has not been cold enough for the ground to freeze. His feet sink deep into the swampy turf; he is becoming very sweaty. There is a smell of mud and iron-rich water.

Soon the trail veers away towards the coppices and brushwood in the direction of Vaikkojoki.

A few ravens croak and caw in the distance through the grey morning air. The vegetation is growing more dense. The trees are shrinking, fighting for space. Spindly pines. Messy grey spruce twigs. Stunted birches: most leaves have blown off, those remaining range from yellow to dull green and grey. He can see no further than five metres in any direction. Barely that.

He is down by the beck now. Has to keep brushing away twigs with his arm. He can only see a couple of metres ahead.

Then he hears the dogs. Three loud barks. Then silence.

He knows what that means. They have tracked down the bear. Disturbed it, forced it to move away from where it was lying wounded. When they detect the pungent smell coming from such a hideaway, they usually bark.

After another twenty minutes he hears the dogs barking again. More persistently this time. They have caught up with the bear. He checks his G.P.S. One and a half kilometres away. They are barking while on the move. Barking and chasing the bear. Best to keep plodding on. No point in getting too excited yet. He hopes the young bitch doesn’t get too close. She is rather excitable. The other bitch works more calmly. Good at standing still a safe distance away, holding the hunted animal at bay, barking. She seldom goes any closer than three metres. A wounded bear is not a patient bear.

After half an hour they start barking from a stationary position. Now both the bear and the dogs are standing still.

Typical! Just where the vegetation is at its thickest. Nothing but undergrowth and no view at all. He keeps going, and is now only two hundred metres away.

The wind is coming from the side. Not a problem. The bear should not be able to smell him. He cocks his rifle. Presses on. His heart is pounding.

It’s O.K., he thinks. He wipes his hand on his trouser leg. A bit of adrenalin goes with the territory.

Fifty metres to go. He peers into the undergrowth where the barking is coming from. Both dogs are wearing jackets that are luminescent green on one side and orange on the other. To distinguish them from the bear in circumstances where that is necessary. And also to see what direction the dog is facing.

Now he sees a glimpse of something orange up ahead. Which of the dogs is it? Impossible to tell. The bear usually stands between the dogs. Mäkitalo screws up his eyes, peers into the undergrowth again, moves as quietly as he can to one side. Ready to shoot, reload, shoot again.

The wind veers again. At the same time he catches sight of the other dog. There are about ten metres between the two of them. The bear must be in there somewhere, but he can’t see it. He must get closer. But now the wind is coming from diagonally behind him. That is not good. He raises his rifle.

Then he sees the bear. Ten metres away. No clear view for taking a shot. Too many tree trunks and too much undergrowth in the way. It suddenly stands up. It must have got wind of him.

It charges at him. It all happens so quickly. He hardly has time to draw breath before it is almost upon him. There is a creaking and crashing and snapping of branches.

He shoots. The first shot makes the bear swerve to one side, but it keeps on coming. The second shot is perfect. The bear collapses three metres short of him.

The dogs pounce on it immediately. Bite at its ears. Chew its fur. He lets them do whatever they want. That is their reward.

His heart is slamming like an open door in a storm. He tries to get his breath back in between praising his dogs. Well done! There’s a good girl!

He takes out his mobile. Rings the local huntsmen.

That was a close shave. A bit too close for comfort. He thinks briefly about his little boy and his partner. Then he banishes any such thoughts from his mind. Looks at the bear. It is big. Really big. And almost black.

*

The local huntsmen arrive. The air is heavy with autumn chill, pungent bear and admiring respect. They truss up the body of the bear with ropes and attach straps running over their shoulders and under their arms so that they can drag it to a clearing not far from a track that can be accessed by their four-wheel drive pick-up. They work like slaves, and agree that it is a hell of a big beast.

The inspector from the county council arrives. He inspects the place where the bear was shot to make sure that no laws have been broken. Then he takes no end of samples while the hunters are recovering from their efforts. He clips off a clump of fur, cuts out a skin sample, cuts off the testicles, prises out a tooth with his sheath knife so that the age of the bear can be established.

Then he cuts open its stomach.

“Shall we check what Teddy’s been eating?” he says.

Mäkitalo has tied his dogs to a tree trunk. They whimper and strain at their leashes. It’s their bear, after all.

Steam rises from the contents of the bear’s stomach. And the stench is awful.

Some of the men take an involuntary step back. They know what’s inside there. The remains of Johansson’s Norwegian elk-hound. The inspector knows that as well.

“Ah well,” he says. “Berries and meat. Fur and skin.”

He pokes around in the slushy mess. His face suddenly assumes a suspicious expression.

“But for Christ’s sake, this isn’t …”

He falls silent. Picks up a few pieces of bone with his right hand, which is protected by a plastic glove.

“What the hell is this it’s been eating?” he mumbles as he pokes around in the slush.

The huntsmen come closer. Scratch at the back of their heads so that the peaks of their caps slide down their foreheads. One of them takes out a pair of glasses.

The inspector straightens up. Quickly. Takes a step backwards. He’s holding a piece of bone with his fingers.

“Do you know what this is?” he asks.

His face has turned grey. The look in his eyes sends shivers down the spines of all the others. The forest has fallen silent. There is no wind. No birdsong. It seems that it is refusing to reveal a secret.

“It’s not a dog in any case. I can assure you of that.”

The autumnal river was still talking to her about death. But in a different way. Before, it was funereal in tone. It used to say: You can put an end to it all. You can run out onto the thin ice, as far as you can before it breaks. But now the river said: You, my girl, are no more than the blinking of an eye. It felt consoling.

District Prosecutor Rebecka Martinsson was sleeping calmly as dawn began to break. She was no longer woken up by angst poking away at her from the inside, digging into her, scratching around. No more night sweats, no more palpitations.

She no longer stood in the bathroom, staring into the mirror at black pupils and wanting to cut off all her hair, or to set fire to something – preferably herself.

It’s good now, she said instead. To herself or to the river. Sometimes to another person, if anybody dared to ask.

And it was good. Good to be able to do her job again. To tidy up her home. Not to feel her mouth constantly parched, not to break into a rash after taking all her medicine. To sleep soundly at night.

And occasionally she even laughed. While the river flowed past as it had done for generation after generation before her, and would continue to flow long after she was no more.

But just now, for the blinking of an eye she would be alive, she could laugh and keep her house tidy, do her job properly and occasionally smoke a cigarette in the sunshine on her balcony. Then she would be nothing, for a very long time.

That’s the way it is, the river said.

She liked to have the house clean and tidy. To keep it as it was in Grandma’s time. She slept in the alcove in the varnished sofa bed. The floor was covered by rag mats made by her grandmother. Wooden trays hung from wall hooks in embroidered slings.

The drop-leaf table and chairs were painted blue, and worn and shiny wherever hands and feet had rested. Crammed onto the metal ladder shelves were volumes of low-church pastor Laestadius’s sermons, hymn books and thirty-year-old copies of magazines from another time – Hemmets Journal, Allers and Land. The linen cupboard was full of threadbare mangled sheets.

Lying at Martinsson’s feet was the puppy Jasko, sniffling away. The police dog handler Krister Eriksson had given it to her eighteen months ago. A handsome sheepdog. He would soon be lord of all he surveyed – at least, that’s what he himself thought. Raised his leg high when he peed, and almost fell over. In his dreams he was the King of Kurravaara.

His paws twitched and trod in his sleep as he chased after all those annoying mice and rats that filled his days with their tempting scents but never allowed themselves to be captured. He yelped and his lips twitched when he dreamed about clamping his teeth into their backs with a satisfying crunching noise. Perhaps he was also dreaming about all the local bitches responding to all the bewitching love-letters he peed onto every available blade of grass during the day.

But when the King of Kurravaara woke up, nobody called him anything but the Brat. And no bitches queued up outside his door.

Martinsson’s other dog never lay in her bed. Never sat in her lap as the Brat frequently did. Vera the mongrel might allow herself to be stroked very briefly, but there was no question of longer spells of tenderness.

She slept under the table in the kitchen. Nobody knew her age, nor her pedigree. She used to live with her master in the depths of the forest, a hermit who made his own anti-mosquito balm and pranced around naked in the summer. When he was murdered, his dog ended up with Martinsson. If she hadn’t taken her in, she would have been put down. Martinsson wouldn’t have been able to cope with that, and so she had taken Vera home with her. And she had stayed there.

In a way, at least. She was a dog who knew her own mind. Who left it up to Martinsson to track her down when she wandered off along the village road, or went off to explore the potato patch down by the boathouse.

“How on earth can you let her wander off like that?” said Martinsson’s neighbour Sivving. “You know what people are like. Somebody will shoot her.”

Please look after her, Martinsson prayed. To a God she sometimes hoped existed. And if you can’t do that, let it happen quickly. Because I can’t stop her. She’s not my dog in that sense.

Vera’s paws never twitched when she was asleep, nor did she go hunting after tempting scents in her dreams. What the Brat dreamed about, Vera did while she was awake. In the winter she would listen for sounds made by field mice under the snow, pounce down upon them and break their backs just as foxes do. Or stamp down with her front paws and kill them off like that. In the summer she would dig out mouse nests, gobble up the naked youngsters and eat horse dung in the pastures. She knew which farms and houses to avoid. She would run past those places, skulking down in the ditches. But she knew where she would be treated to cinnamon buns and slices of reindeer meat.

Sometimes she just stood there, staring into the north-east. On such occasions Martinsson would get goose pimples. Because that was where the dog’s original home was, on the other side of the river, up in Vittangijärvi.

“Do you miss him?” Martinsson would ask on such occasions.

And was pleased that only the river could hear her.

Now Vera woke up, sat on the floor next to the head of the bed and stared at Martinsson. When Martinsson opened her eyes, Vera started wagging her tail.

“You must be joking,” Martinsson groaned. “It’s Sunday morning. I’m asleep.”

She pulled the covers up over her head. Vera lay her head on the edge of the bed.

“Go away,” Martinsson said from under the covers – although she knew it was too late now: she was wide awake.

“Do you need to pee?”

Whenever she heard the word “pee”, Vera usually sat down next to the door. But not this time.

“Is it Krister?” Martinsson asked. “Is Krister on his way here?”

It was as if Vera could feel when Krister Eriksson got into his car in Kiruna, fifteen kilometres away from the village.

In reply to Martinsson’s question, Vera walked over to the door and lay down to wait.

Martinsson collected her clothes that were hanging over a chair back next to the sofa bed, and lay on them for a few minutes before getting dressed under the covers. It was freezing cold in the house after the minus temperatures of the night, and you couldn’t just leap out of bed and put on icy cold clothes.

As she sat on the lavatory, both dogs assembled in front of her. The Brat put his head on her knee and insisted on being stroked.

“Time for breakfast now,” she said, reaching for the toilet paper.

Both dogs dashed out into the kitchen. But when they noticed that their food bowls were empty, it seemed to dawn on them that the alpha-female was still in the bathroom, and they raced back to Martinsson. By now she had flushed the toilet and washed her hands in cold water.

After breakfast the Brat went back to the warm bed.

Vera lay down on the rag mat next to the hall door, settled down with her nose on her front paws, and sighed deeply.

Ten minutes later a car drew up outside.

The Brat shot out of the bed in such a rush that the covers were scattered in all directions. He dashed under the dining table, raced up to Martinsson, then to the door, then to the bed and repeated the same operation. The rag mats were sent flying, he slid over the varnished wooden floorboards, and kitchen chairs fell over.

Vera had stood up, was standing there patiently and also wanted to be let out. Her tail was wagging away, but she didn’t overdo things.

“I really don’t understand what you’re trying to tell me,” said Martinsson innocently. “You’ll have to explain yourselves more clearly.”

And the Brat whimpered and yelped and stared pleadingly at the door, running up to it and then back to Martinsson.

Martinsson walked extremely slowly to the door. In slow motion. Looked unremittingly at the Brat, who was shaking and trembling with excitement. Vera just sat there, anticipating the inevitable. Martinsson turned the key and opened the door. The dogs bounded down the steps.

“Oh, was that what you wanted?” she exclaimed with a laugh.

*

Eriksson the police dog handler parked his car outside Martinsson’s house. Even from a distance he had noted that there was a light in her kitchen window on the upper floor, and his heart gave a little leap of joy.

Then he opened the car door just as Martinsson’s dogs came rollicking down the steps.

Vera was first. Her hindquarters were swinging from side to side, and she hunched her back in sheer pleasure.

Krister’s own two dogs, Tintin and Roy, were two hard-working, handsome, well-disciplined and pedigree sheepdogs. Martinsson’s Brat was Tintin’s son. He was destined to be a super-dog.

And so Vera, a vagrant with no pedigree at all, had become a member of the gang. As thin as a rake. One of her ears stood straight up, the other was limp. And she had a black patch around her eye.

To start with he had tried to train her. “Sit!” he had said. She had looked him in the eye and put her head on one side. If I could understand what you meant, well, maybe – but if you’re not going to eat that tasty-looking bit of liver, then perhaps …

He was used to dogs obeying him. But her he could not charm.

“Hello, you scruffy little mongrel!” he said, tugging gently at her ears and stroking her head. “How can you be so slim when you spend all your time gobbling?”

She allowed herself to be stroked, then made way for the Brat. He was running around like a cat with a firework up its bottom – between Eriksson’s legs, all over the place, couldn’t stand still long enough for Eriksson to stroke him, then lay down totally submissive – then up again, stood up with his paws on Eriksson, lay down once more on his back, twirled around, then ran off and fetched a pine cone that they might be able to play with, dropped it at Eriksson’s feet, licked Eriksson’s hand then yawned – one way of getting rid of some of those feelings that had become too much to cope with.

*

Martinsson appeared in the porch. He looked at her. Beautiful, beautiful. Her arms crossed and her shoulders up by her ears to keep in the warmth. The contours of her small breasts were visible through her military-style vest. Her long dark hair was slightly tousled in a just-out-of-bed way.

“Hello!” he s. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...