- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

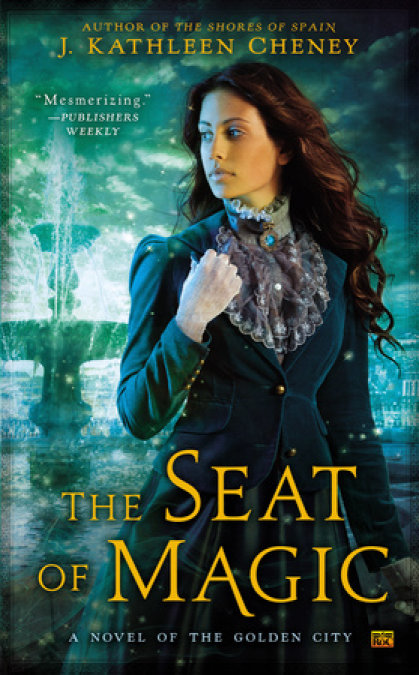

Synopsis

The Golden City series continues, and humans and nonhumans alike are in danger as evil stalks the streets, growing more powerful with every kill…

It’s been two weeks since Oriana Paredes was banished from the Golden City. Police consultant Duilio Ferreira, who himself has a talent he must keep secret, can’t escape the feeling that, though she’s supposedly returned home to her people, Oriana is in danger.

Adding to Duilio’s concerns is a string of recent murders in the city. Three victims have already been found, each without a mark upon her body. When a selkie under his brother’s protection goes missing, Duilio fears the killer is also targeting nonhuman prey.

To protect Oriana and uncover the truth, Duilio will have to risk revealing his own identity, put his trust in some unlikely allies, and consult a rare and malevolent text known as The Seat of Magic…

Release date: July 1, 2014

Publisher: Ace

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Seat of Magic

J. Kathleen Cheney

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHAPTER 1

SUNDAY, 19 OCTOBER 1902

The library of the Ferreira home housed a collection of items Duilio’s father had brought back to the Golden City from his travels on the sea. A large round table stood in the center of the room, the polished marquetry surface half hidden by a collection of sun-bleached giant clamshells. The chandelier of white coral above it had never been refitted for gas lighting and so held candles that Duilio rarely lit. He kept the thing for its beauty instead. The shelves were lined with books of varying antiquity and origin, purportedly filched from this or that hidden stockpile during his father’s many adventures with the prince’s father years and years ago.

Duilio didn’t concern himself over the books’ provenances; he was more interested in reading them. Neither his father nor his elder brother had been fond of books, and his mother preferred to read her newspapers in her sunny front sitting room, so he usually had the chillier library to himself.

He’d selected a volume in French, cheaply bound in dark blue fabric—Les sirènes du Portugal—that called itself a truthful account of life among the sea folk, the sereia. The gold lettering on the spine was nearly illegible, worn from the many times he’d read the book as a young man. Duilio doubted its accuracy, but it served better than nothing. Even so, the cities of the sereia’s islands were depicted therein as pale reflections of human cities like the Golden City and Lisboa. There had to be more to their civilization, Duilio reckoned, but the author—one Monsieur Mathieu Matelot, a pseudonym if he’d ever seen one—apparently hadn’t had the access needed to make a decent study of their culture. Given how little most humans knew of sereia, the author wasn’t bound by the truth. Duilio set the volume on the small table next to his chair, wondering what Oriana would think of it.

Almost two weeks now, and he’d not heard a word. He leaned back in the leather chair and sighed, well aware that fretting did no good. Perhaps he should have gone to Mass with Joaquim this morning and prayed.

“Duilinho?” His mother had come into the library, a coffee cup and saucer in one hand, her newspaper in the other. Near fifty, she bore her age well—better than a human woman would. She wore a brown wool day dress that showed that despite having borne three sons, she’d retained her figure. Her dark hair, worn in a high bun this afternoon, likely didn’t require any padding, an innate advantage of being a selkie. She regarded him with troubled brown eyes. “Hiding again?”

Yes, he was. He’d returned from a late lunch with his cousin Rafael Pinheiro only to learn his mother had a visitor, Genoveva Carvalho. He’d ducked into the library rather than face the girl. The eldest Carvalho daughter had recently shown an interest in him, an interest that wasn’t reciprocated. True, she was a lovely girl from a good family. Her father had spoken to Duilio early that summer about arranging a marriage between them, but Duilio had declined the proposition. Unfortunately, the young lady appeared to believe persistence would wear him down. She’d visited five times over the last two weeks, an uncalled-for number of visits when it was obvious his mother didn’t care for society.

Duilio rose, laying down his book. “I’m afraid so, Mother. Thank you for dealing with her.”

“What else am I to do? I know you haven’t encouraged her.” She held out the paper. “I realize it’s Sunday, but I’m surprised no one has come to tell you. Maraval is dead.”

Duilio took the newspaper. She’d folded it so one column showed, headed by an article proclaiming that the Marquis of Maraval, the Minister of Culture, had been killed. Duilio scanned the printed words, grimacing when the newsprint smeared onto his fingers.

In a misguided attempt to recapture the past glory of the Portuguese Empire, Maraval had conspired to create a Great Magic, one that would change history. But his grand spell had been fueled by the deaths of dozens of servants. They’d been placed in pairs inside a large work of art under the waters of the Douro River, left to drown when the river’s water seeped into their prisons of cork and wood. The plot had only begun to unravel when the conspirators chose the wrong pair of girls to sacrifice—Lady Isabel Amaral and her hired companion, Oriana Paredes. Miss Paredes was one of the few servants on the Street of Flowers who, when placed under water, would survive. A sereia, or sirène as the French book called them, she had gills and could breathe water, which gave her time to escape. Unfortunately she hadn’t been able to save her mistress. She’d done her best to bring Lady Isabel’s killers to justice instead. The newspaper stated that the young lady’s father had gone one step further. The usually indolent Lord Amaral had gained entrance to the prison the previous evening and delivered the marquis up to a higher court of justice. Given that Duilio had been instrumental in the capture of the marquis, the police should have sent him a note at the very least.

“This doesn’t say what’s been done to Lady Isabel’s father,” he noted. “I’m relieved there’s no mention of the man’s motive.”

The Golden City’s newspapers, elated over a scandal to report, had been surprisingly circumspect in one regard—they hadn’t mentioned the names of Lady Isabel or her companion in connection with Maraval’s plot. Instead they’d published that Isabel had been murdered by bandits who grabbed her off the street for her jewelry. It was the only concession Duilio had asked of the Special Police handling the case, a request made to protect Oriana Paredes rather than Lady Isabel. Oriana would not have withstood the attention of the media. Nonhumans had been banned from the Golden City for almost two decades now, and the fact that she was a sereia would have been exposed as the reason she’d survived when Lady Isabel hadn’t.

His mother took the paper when he handed it back. “I noted that as well. It will make things easier when Miss Paredes returns.”

Duilio frowned, wishing he knew when that return would occur. Oriana hadn’t been certain what reception she would receive when she reached her people’s islands. He hoped things hadn’t gone badly.

His mother touched the polished table and then frowned when her fingers left inky streaks behind. Since much of the staff was off on Sunday mornings, the newspaper must not have been ironed to set the ink. “Duilinho, sitting here and fretting is not going to bring Miss Paredes back.”

He’d been thinking the same thing only a moment before. He drew a linen handkerchief from the inside pocket of his charcoal morning coat and handed it to her. “I know, Mother, but she told me she would try to return to us. It worries me that we’ve heard nothing.”

One arched brow rose. “To us?”

Duilio pressed his lips together, refusing to rise to his mother’s bait.

She sighed, wiped the table with the handkerchief, and then inspected her fingers. “I cannot tell you what keeps her. I wish I could.”

Despite sharing the ocean, his mother’s people rarely interacted with the sereia. He sighed. “I should have convinced her not to go.”

His mother looked up at him, her limpid brown eyes thoughtful. She had delicate features and a pointed jaw, neither of which he’d inherited. He had his father’s rectangular face, very human in appearance, with a wide brow and square jaw. He often wished he looked more like her, as his elder brother Alessio had.

“Do you believe you could have dissuaded her?” she asked.

“I had a bad feeling, Mother.” Like his father and brother before him, he was a witch—a seer. His gift was erratic and refused to answer the questions he most wanted answered, but when he did have an answer, it was reliable. “I wish I’d begged her to stay.”

“She would not have given in, Duilinho,” Lady Ferreira said as she handed back the smudged handkerchief. “Do not think her weaker merely because she is female.”

He’d never been one to believe women weak and helpless. His mother, with her soft voice and gentle ways, was far stronger than others guessed. “I will keep that in mind, Mother.”

“Good.” She took a deep breath, as if preparing to launch into a speech. “Now, I wish to ask a favor.”

She rarely asked anything for herself. “What is it?”

“I would like you to take me to see Erdano,” she said. “I think I am ready.”

Her eldest son, Erdano, lived north of the city at Braga Bay. A small bay, inaccessible to larger boats, it was a safe place for the selkie harem to call their own. But as it lay north of the river’s mouth, the trip was safest made by boat. For all of her familiarity with the sea, his mother wasn’t a sailor. One of the perquisites of being a gentleman, though, was that he was frequently at leisure to indulge his mother’s whims. “When do you want to go?”

“Tomorrow morning, I think,” she said. “Before I lose my nerve. I . . .”

A discreet cough in the hallway heralded the approach of Cardenas, the family’s elderly butler. A vigorous man in his seventies, he was the longtime guardian of the family’s consequence—whether or not that was merited. Duilio stepped forward, since Cardenas looked to him first.

“A visitor,” he told Duilio, his voice tight with disapproval. “One of those. He didn’t give his name.”

For the last two weeks Duilio had been facing down a string of Alessio’s old lovers. They’d slipped cautiously up to the door of the Ferreira house, the ladies veiled and the gentlemen with their hats lowered to hide their faces. At the Carvalho ball a couple of weeks ago, Duilio had revealed to an acquaintance that Alessio had kept journals of his romantic exploits. He’d not realized then how much time he would have to spend smoothing ruffled feathers as a result. He touched his mother’s elbow. “I’d better go take care of this, Mother. We’ll go in the morning, after breakfast if you’d like.”

She nodded gracefully, and Duilio accompanied the butler down the hallway toward the front sitting room. “Would you inform João that I’ll need the paddleboat in the morning?”

“Of course, Mr. Duilio,” the butler said. He withdrew a note from his waistcoat’s pocket. “And this came from Mr. Joaquim while you were out.”

Duilio stashed the note in a pocket. Probably the news about Maraval’s death that he should have seen earlier. He thanked the butler and stepped over the threshold into the sunny front sitting room. Like most of the rooms in the house, this showed the touch of his mother’s taste, all soft browns and ivories. Before the unlit hearth a pale beige sofa in leather and a group of chairs upholstered in ivory brocade surrounded a low table that served to invite conversation. The windows on the far wall looked out toward the Queirós house, but from the right spot Duilio could catch the glittering of the sun on the Douro River.

His newest visitor rose from the armchair in which he’d been sitting. A tall gentleman near his own age, the visitor looked familiar, but Duilio couldn’t quite place him. He was a striking man, with a handsome face and a marked widow’s peak from which black hair swept back neatly. His fine frock coat, matching waistcoat, and pinstriped trousers marked him as a gentleman. He had a charismatic air, which made Duilio wonder who he was. People like him usually attracted attention. But as Duilio had been abroad for a few years following his departure from the university at Coimbra, there were always people in society he didn’t know—although he’d worked hard in the last year to overcome that. Knowing society was his specialty.

“I’m afraid I don’t recall your name, sir,” Duilio began.

The visitor’s lips twisted in amusement. “I’ve never told you my name.”

That implied they had met before. “Do we know each other?”

“I was a friend of your brother’s.”

Duilio felt a sudden flare of recognition, placing where he’d seen that face before—years ago in Coimbra, where students from the same town would often rent a house together. On his arrival at the university, Duilio hadn’t wanted to live in his brother’s shadow so he’d found a different house to live in, but this man had been one of Alessio’s housemates. His widow’s peak and aquiline nose were a distinctive combination. “You and Alessio lived in the same república at Coimbra,” Duilio said. “I recall seeing you there when I visited him, but I don’t believe he ever introduced us.”

“Very good.” The man nodded approvingly, as if Duilio had passed a test. “I was not, by the way, one of his lovers.”

Duilio turned toward the marble mantelpiece to hide his smile. He was always amused by the swiftness with which others felt they had to inform him of that. It usually came within a few sentences of admitting they’d known Alessio. He suspected many of those quick denials were false. “So is this visit concerning his journals? I have no intention of publishing them, nor are they for sale.”

“May we sit down?” the gentleman asked.

Duilio stared back at him expectantly. “May I ask your name?”

“You may call me Bastião,” his visitor said after a split-second hesitation.

That definitely wasn’t the man’s name. Duilio gestured toward the pale leather couch anyway. The man settled there, and Duilio sat in the chair across from him. “Now, Bastião, what brings you to my house?”

“A number of things,” the man said, “but primarily to discover if you know why Alessio was murdered.”

Duilio did his best to keep his reaction from reaching his face. “My brother was killed during a duel. Why would you say he was murdered?”

“From what I understand,” the man said, “his opponent fired into the air, making one question how Alessio could have been shot in the chest. We know that the Marquis of Maraval had it done, fearing that Alessio would seduce the prince out from under his influence. That, however, was not the true reason behind Alessio’s occasional visits to the palace. He was working as an agent of the infante.”

Duilio kept from gripping the arms of the chair only by sheer will. Following Maraval’s arrest by the Special Police, their inspection of his private papers had revealed his mistaken assumption and decision to have Alessio killed. That last claim, though, was new. “I was unaware the infante has agents. He’s under house arrest in the palace. No one is allowed to visit him.”

Strictly speaking, that was a lie. In the last month Duilio had met a team of four investigators who were, as far as he could tell, working for the infante. That could be viewed as treason so long as his elder brother, Prince Fabricio, held the throne. When Duilio asked, the group of investigators hadn’t admitted the association. They hadn’t denied it either.

Bastião crossed one long leg over the other. “Alessio was acting as a messenger between the infante and Dinis. That was what took him to Lisboa so often.”

Cold spread through Duilio’s stomach. What had Alessio been up to? Prince Dinis II ruled Southern Portugal, which Alessio had visited regularly in the last year of his life. Perhaps this Bastião was trying to determine whether Alessio had revealed any such activities in his journals. But if Alessio had worked for the infante, he’d not recorded a word about it. “Why would my brother do so? He was never fond of the throne.”

Bastião smiled. “No, he believed things needed to change.”

Alessio hadn’t been a revolutionary, but he’d thought the usefulness of the twin monarchies of Northern and Southern Portugal was long past. “And you’re suggesting his efforts in the infante’s name were . . . ultimately intended to reform the monarchies?”

Bastião interlaced his fingers over his knee, looking perfectly at ease as he talked about treason. “Are you asking if I know the infante’s leanings?”

Duilio watched him carefully. His gift spoke into his mind, warning him that this meeting—this man—was important. Unfortunately, it didn’t tell him how. “Do you?”

“I also act in his name at times,” Bastião said, “so I know his mind on certain matters.”

Duilio pressed his lips together. Why had this man come to tell him this? That the infante of Northern Portugal was bypassing his elder brother didn’t concern Duilio overmuch. He’d walked that line for years himself. He was half selkie; living in the city at all was illegal for him. And he’d willingly harbored Oriana Paredes, a sereia spy, in his household.

“I know where the infante stands on the issue of nonhumans as well,” Bastião added, as if he’d read the path of Duilio’s thoughts.

“How interesting,” Duilio said in what he hoped was a neutral tone. He had a feeling this man Bastião was trying to winnow out his personal leanings on the matter. He didn’t intend to be drawn. Not when he didn’t know who this man was.

Bastião smiled at his vague comment, apparently recognizing it for evasion. “The infante could not, after all, be friends with Alessio Ferreira if he felt nonhumans were to be abhorred.” His eyes flicked downward to consider the kid-gloved fingers laced over his knee. “The ban on nonhumans is a ridiculous abuse of power by the prince.”

Did that mean this Bastião was aware the Ferreira family wasn’t purely human? Or had he thought Alessio a Sympathizer? “Seers have predicted the prince will be killed by a nonhuman,” Duilio pointed out. “Is that not sufficient reason for the ban?”

“Something will kill each of us one day,” Bastião said with a shrug. “Shall we banish the river to assure no one drowns?”

That was, word for word, what Alessio had said once when speaking of the ban. This man had to have known him.

Duilio rose and crossed to the mantel again. At least he now had a better answer to why his brother had been killed, a reason more dignified than being killed in a duel over a lover or because of Maraval’s strange idea that Alessio would seduce the prince. This new information made sense of what had previously seemed a pointless death . . . even if it meant that Alessio had been committing treason. “So if you’re not here about Alessio’s journals, what do you want from me?”

“Society seems to have painted you as a dullard, you know, Ferreira,” Bastião said. As he’d worked hard to cultivate that image, Duilio didn’t argue. “Yet Alessio once told me you got all the brains in the family, while he got all the beauty. I wanted to see for myself if that was true.”

Alessio had been fond of saying that, even if it was insulting to both of them. “Very well, you’ve seen me.”

“And if your infante needs your services, will he be able to call on you?”

Now that was a dangerous question. Duilio considered Bastião with narrowed eyes. Someone had sent this man to pry into Duilio Ferreira’s political leanings—a fruitless task, since he wasn’t entirely sure of them himself. Would he serve the infante in defiance of a prince he found detestable? Was his distaste for the current prince grounds to risk his life as Alessio had? Duilio decided evasion was his safest course. “I’ll answer that when the infante asks me himself.”

Bastião rose, a wry smile twisting his lips. “I’ll leave you then, to decide that another day. I’ll show myself out.” Nodding once in farewell, he walked out of the sitting room. A moment later, Duilio heard Cardenas speaking to the man, and the front door closed behind him.

Duilio paced the strip of Persian rug behind the couch, trying to parse out what had just happened. He’d endured enough bizarre interviews in the last two weeks that not much surprised him, but this one had been different. The fact that Bastião had known Alessio at Coimbra a decade ago wasn’t enough to ensure his loyalties. Duilio had no way to know for whom the man worked now.

After a moment Duilio stopped pacing and withdrew Joaquim’s note from his coat pocket. He read the contents and quickly stepped out into the hall, calling for Cardenas.

The butler emerged from the end of the hallway. “Yes, sir?”

“I need my gloves and hat immediately. I’m heading out to the cemetery.”

Cardenas frowned. “It’s Sunday, Mr. Duilio.”

“Unfortunately, the dead don’t honor the day of rest.”

CHAPTER 2

Inspector Joaquim Tavares perched on a stool at the far end of the barren stone cell. It was chilly in these rooms. This row of cells with their unadorned granite walls, once dedicated to prayer and meditation, was perfectly suited for preparing the poor of the city for burial. The Monastery of the Brothers of Mercy had once stood on the Street of Flowers not far from where Duilio’s house was now, but had been moved to this spot high above the river, outside the Golden City’s medieval walls. That placed it close to the city’s seminary for orphans. When the city had set a new cemetery in this area in the mid-nineteenth century, the brothers had been the natural choice to handle the final disposition of paupers.

The girl on the stone slab was destined for one of those pauper’s graves marked with a small stone cross. Slim and pretty, with her dark hair trailing off to one side, she lay on the slab as if asleep. Joaquim knew her name—Lena Sousa—but little more. It likely wasn’t her real name anyway. She’d been found Saturday, crumpled in a doorway on Firmeza Street, by the elderly woman who owned the home. There had been no blood, no sign of any injury, and her small coin purse had still been in a pocket sewn into the seam of her skirt. If Joaquim hadn’t been notified, she would have gone to her grave nameless. Her disappearance had been reported to the police by another prostitute the afternoon before. Her life had come down to a few lines written on a report and a tattered photograph, quickly forgotten, one of too many dead in a city of this size. The paperwork had been handed off to Joaquim but he had no way to find her family, not without her true name or hometown, so the police turned the body over to the brothers.

But something had told Joaquim not to let this one go.

When he’d asked to have the body autopsied, his captain shrugged it off. The police didn’t have the funds for a skilled physician’s services every time a prostitute died, particularly when there was no indication of violent death. Joaquim had considered applying to the medical college but that would have taken longer than he liked. So he’d taken a step he wouldn’t have been willing to pursue if he hadn’t needed answers—he asked Duilio to pay for the doctor’s time. The money was nothing to Duilio, so now Joaquim sat in this cold cell on a sunny Sunday afternoon, his jaw clenched and his stomach churning.

The girl hadn’t been dead long so there was surprisingly little smell, but watching a doctor take apart a young woman and put her back together always bothered Joaquim. He had never developed the strong stomach he needed for this job.

A discreet tap at the door preceded portly Brother Manoel opening it to allow Duilio inside. Joaquim gestured him over to another empty stool, and Duilio came, looking winded as if he’d run all the way from his house. Likely he had. He shifted his morning coat as he settled atop one of the other stools, then adjusted his well-tied necktie. Joaquim might accuse his cousin of being a dandy if Duilio’s up-to-the-mark garb didn’t make him self-conscious about the shabbiness of his own brown tweed suit.

Joaquim shot a glance at the doctor’s square shoulders. He didn’t know Dr. Teixeira well, but he’d run across the older man at Mass several times. Teixeira hadn’t looked up from his work at Duilio’s intrusion, occupied with replacing things he’d previously removed. Joaquim turned away, glad he hadn’t eaten lunch.

“How long have you been here?” Duilio asked.

“Hours,” Joaquim said with a heavy sigh. “I’m sorry I didn’t get to see Rafael before he headed back to Lisboa. But I caught Dr. Teixeira at Mass and he preferred to do this right away. You’ll be paying extra, by the way, for doing this on a Sunday.”

Duilio shrugged. “So what has he found?”

“Nothing. Not yet.”

“Poison?”

“No sign of it,” the doctor intoned without glancing over. “There’s surprisingly little bloating, though, despite the time passed since her death. I don’t know that it’s pertinent.”

Duilio got to his feet and crossed the room to where the doctor was replacing the last of the organs he’d removed. Not willing to miss anything exchanged there, Joaquim followed, doing his best not to look at the body lying on the table.

“There are, of course, poisons we can’t trace,” Teixeira added, “but we usually see some damage in the affected organ. Nothing here looks out of the norm except for the heart.”

Duilio leaned closer to peer down at the body, probably looking inside, which was a ghastly thought.

“Is there a poison that affects only the heart?” Joaquim asked.

The doctor shook his head. “Not this way. Not that I’ve ever seen before. It’s possible one exists, but . . .” He exhaled and said, “If you look at the damage to the heart and the tissues around it, it resembles damage done by a bolt of lightning. But that’s not what happened to her.”

“Why not?” Duilio asked.

The doctor laid his hand somewhere on the body and Joaquim forced himself to look. The doctor had pulled the sheet back up to cover most of the girl’s body and her skin had been pulled closed, saving Joaquim from casting up the nonexistent contents of his stomach, but the long incision running down the center of her chest and up to each shoulder was grisly enough. The doctor pointed to the skin above the girl’s left breast. “No evidence of an entry or exit. When lightning strikes, the electricity passes through the body and usually leaves a burn on each end. This is localized to the tissues directly around the heart.”

Joaquim looked up at him. “And what would do that?”

Teixeira glanced over at Duilio and then back. “How familiar are you with healers?”

“A healer did this?” Duilio asked before Joaquim had the chance.

The doctor shook his head. “That’s not what I said. But”—he scowled down at the body—“keep in mind that I haven’t seen this kind of thing in a very long time. When I was a young man at the medical college, I had a chance to observe a healer at work. They don’t actually heal, you know. Instead they encourage the body to heal itself. They can control the flow of not only the blood, but of energies in the body.”

Joaquim estimated Teixeira’s age between forty-five and fifty, although on the younger end of that spectrum. Teixeira’s dark hair had little gray in it and he seemed in the prime of his life. That would put this memory of the medical college twenty years or so past.

Duilio crossed his arms over his chest. “Do you mean electricity?”

“That isn’t the term they use for it,” the doctor said patiently, “but there are similarities between tissues that have been damaged by an accidental electrical discharge and tissues that have been . . . manipulated&#

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...