- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

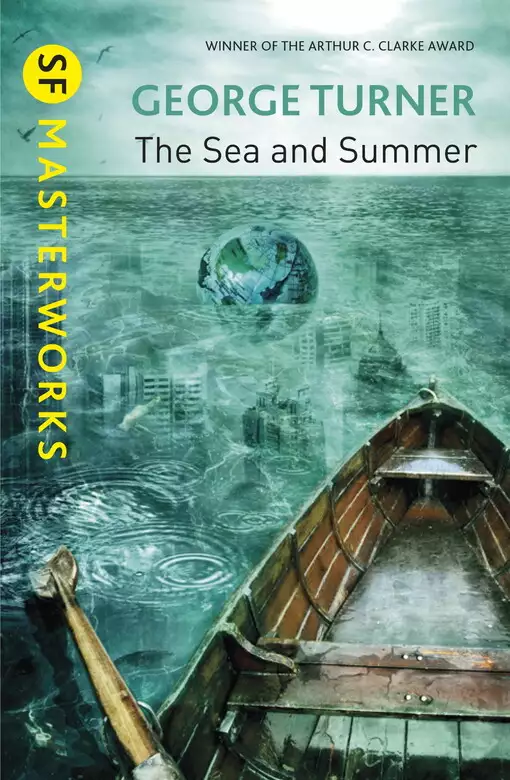

Francis Conway is Swill - one of the millions in the year 2041 who must subsist on the inadequate charities of the state. Life, already difficult, is rapidly becoming impossible for Francis and others like him, as government corruption, official blindness and nature have conspired to turn Swill homes into watery tombs. And now the young boy must find a way to escape the approaching tide of disaster. The Sea and Summer, published in the US as The Drowning Towers is George Turner's masterful exploration of the effects of climate change in the not-too-distant future. Comparable to J.G. Ballard's The Drowned World, it was shortlisted for the Nebula and won the Arthur C. Clarke Award. Winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award for best novel, 1988

Release date: March 14, 2013

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 382

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Sea and Summer

George Turner

George Turner was born in Melbourne in 1916, but did not publish any SF until Beloved Son in 1978. From then until his death in 1997, he produced six SF novels. The Sea and Summer (published in the USA as Drowning Towers) is the best known of them: in the UK, it won the second Arthur C Clarke Award. Alongside his SF work, he was a distinguished literary figure in Australia: he published several mainstream novels, an autobiography, and a good deal of literary criticism.

The Sea and Summer tackles a subject that’s a common part of public discourse now, but was much more marginal then: climate change, and the effect it might have on our society. There are two threads to the book. The main one, ‘The Sea and Summer’, takes place in the mid-21st century, as these effects have become visible: Melbourne is flooded and basking in the warmth of an endless summer. A framing narrative, ‘The Autumn People’, is set centuries later. A new Ice Age is in prospect, and a writer is trying to make sense of how people thought in the ‘Greenhouse centuries’.

The Sea and Summer isn’t just about environmental issues, though. It has far broader political concerns – and, moreover, a sense of how all the influences on a society interact and affect individuals. Turner’s 21st century is one of sharp divisions between the rich and the poor (the ‘Sweet’ and the ‘Swill’), with a sense that it’s all but impossible for people to move up the ladder. The story is told from several different perspectives and across a number of years and avoids simplistic explanations of what might have caused this situation or how it might be solved. In this respect, it’s reminiscent of John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar (1968), Thomas M. Disch’s 334 (1972) – or, more recently, Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2312 (2012). These books – which might be called mosaic novels – use multiple viewpoints to give a sense of their society at all levels. Several of them also track characters progressively growing older, their attitudes shifting as their experiences do. In The Sea and Summer, there’s also a serious attempt to discuss how history works and how people might be able to influence it. Consider, for instance, Teddy’s encounters with ideas of Utopia in Chapter 13. Both this and the framing narrative can be seen as offering further perspectives on Turner’s world. It is not in any sense predestined that things have to be this way; so how might they be otherwise? How could a different world be built? That’s not to say this book is only about ‘issues’: the characters are sharply differentiated, and the writing is vivid and sometimes beautiful (for an example of the latter, see Alison’s paean to summer in Chapter 1).

In his Postscript to the novel, Turner strikes a modest note about the power of predictive SF: ‘This novel cannot be regarded as prophetic; it is not offered as a dire warning. Its purpose is simply to highlight a number of possibilities that deserve urgent thought.’ But we shouldn’t be surprised if, given the detail and thoughtfulness of his extrapolations, much of what the book describe does come to pass. For instance, he posits a collapse of the financial system in the mid-21st century. Although the world did not suffer such a collapse in 2007–8, it came perilously close to one: it was certainly possible to see what that abyss looked like. Not exactly a prediction come true, then, but certainly an issue that deserves urgent thought.

The word that most comes to my mind when trying to describe The Sea and Summer is ‘scope’. Even though it focuses on only one place, it seems as if Turner has thought about every aspect of his future. Everything fits together, we are shown precisely what we need to understand his world, and his vision has an encompassing power that is as compelling as prophecy.

Graham Sleight

The sun, high in early afternoon, sparkled on still water. There was no breeze; only the powercraft’s wake disturbed the placid bay. The pilot’s chart showed in dotted lines an old riverbed directly below his keel, but no current flowed at the surface; the Yarra now debouched some distance to the north, at the foot of the Dandenongs where the New City sheltered among hills and trees.

The pilot had lost his first awe of the Old City and the vast extent of the drowned ruins below; this was for him a routine trip. He carried hundreds of historians, archaeologists, divers and sightseers in the course of a year. His thought now was simple pleasure that the sun had power enough to have made it worthwhile to shed his clothes and enjoy its warmth on his skin.

There were not many such days, even in midsummer, and the southern wind would bring a chill before nightfall. Enjoy while you may, he thought, snatch the moment. And if that edged a little too close to hedonism for a practicing Christian, so be it. He believed in the forgiveness of sin rather than in the possibility of his own perfection.

When this sunken city had reached its swollen maximum of population and desperation, a thousand years before, the sun had blazed throughout the four seasons, but that time was over and would not return. The Long Summer had ended and the Long Winter – perhaps a hundred thousand years of it – loomed. The cold southern wind at nightfall, every nightfall, was its whisper of intent and the pilot was happy to be living now rather than earlier or later.

Not every wall and spire of the Old City lay below the bay. The melting of the Antarctic ice cap had been checked as the polluted atmosphere rebalanced its elements and the blanket of global heat dissipated; the fullest rise of the ocean level had been forestalled though not soon enough to avert disaster to the coastal cities of the planet. To the north and northeast of the powercraft’s position lay the islands which had been the higher ground of Melbourne’s outer suburbs, forested now and overgrown, but storehouses of history.

The other ruins, the other storehouses, part submerged, were clusters of gigantic towers built (with the blind persistence of those who could not believe in the imminence of disaster) in the lower reaches of the sprawling city. There were ten Enclaves, each a group of nearly identical towers whose designs had varied little in the headlong efficiency of their building. The Enclave now approached by the powercraft was one of the largest, a forest of twenty-four giants evenly spaced in an area of some four square kilometers opposite what had been in that far time the mouth of the Yarra. It was shown on the pilot’s chart as Newport Towers, with the caution Erratic Currents, a notation common to all the Enclaves. These ancient masses, each more than 100 meters on a side, created races and eddies at change of tide.

Marin knew that what he saw were only the lower hulks of buildings which had stretched at the sky. Their greedy height had not withstood the eroding sea and the cyclones of destabilized weather patterns. Not one had endured entire; most were only sub-surface stumps of their hugeness, splintered jawfuls of broken teeth. It was difficult to conceive of them in their unpleasant heyday, twenty-four human warrens, each fifty to seventy stories high and verminous with the seething humanity of the Greenhouse Culture.

He lived in a world where architecture favoured concern for surroundings, where stairways were thought of as an inconvenience and two-floor dwellings a rarity; processing conditions occasionally demanded excessive height in factories and these were bounded by restrictions of design and position. (It was estimated that in Old America some structures had approached a kilometer in height and there was much argument about the pressures that had produced such extravagance.)

He was bored with the Enclaves as such; there seemed little more to be discovered in their catacomb silence although today’s fare seemed to find them a lifetime study. And not so much ‘them’ as a particular one.

He asked over his shoulder, ‘Tower Twenty-three, Scholar? As usual?’ and she agreed, ‘As usual.’

The powercraft was a large one and the two passengers astern were sufficiently removed to speak quietly without his hearing, but he had the usual human awareness of being talked about, sensing the small alteration of timbre in the susurrus of speech.

The man asked, ‘Does he always use the formal address? That must be the tenth time.’

‘Always.’ The historian was amused. ‘The Christians are a punctilious lot, always polite but conscious of sanctity – not plainly apart but not wholly of the common herd.’

‘Insulting!’

‘No, only defensive. They feel themselves to be a rapidly decreasing minority as the contemplative oriental philosophies gain ground. And fools do tend to sneer at them.’

‘Do you wonder? Anyone who thinks he can draw a line between good and evil is at best mistaken, at worst demented. The Christians as I understand them want to save mankind from sin without first understanding either sin or mankind.’

She smiled at him. ‘Do you believe that or are you roughing out an epigram for your play?’

Because she had prodded a real weakness the actor-playwright contented himself with an enigmatic shrug; she had an unerring aim for small vanities and in the twenty-four hours of their acquaintance had made him aware of it. There was, for instance, his claim to Viking ancestry, based solely on his name, Andra Andrasson, though a strong Aboriginal strain coloured him unmistakably; the dark skin made it necessary for him to use a heavy Caucasian makeup for most roles and as a consequence he often went unrecognized in the public street. ‘Who wants to be pestered by fans?’ he had asked and had been almost able to hear her unspoken, You’d love it. Which he would.

Establishing the tutor-student relationship, no doubt. That was better than a predatory interest in a good-looking young man (thirty – er, – five is young enough); he had learned a healthy fear of footloose older women at first-night parties. This one, at any rate, was all tutor and chattily disinterested when not busily informing.

Lenna Wilson was not, in fact, wholly disinterested, merely unaroused – more accurately, a little disappointed. She had been properly excited at the request for consultation from one of the foremost stage personalities of the day and more than a little stimulated by his presence and his easy handsomeness. Then, on this first excursion, he had seized the chance to sunbathe and demagnetization had set in. In the nude he was curiously shapeless – tubular was her mute description – as though form were the gift of his tailor, and in movement he displayed little grace. Yet on stage he could mesmerize with a gesture, put on majesty, collapse into clowning or be instantly a nameless man in the street.

Well, each to his talent and hers was for history. She was as respected in her niche as he in his (though about one tenthousandth as well known) and he had confirmed his knowledge of this by the string pulling he had done to obtain her agreement to coach him for a single force-fed week.

She said, ‘Don’t expect too much here. It’s easy to be let down at first sight.’

‘I expect to be horrified.’

‘By empty rooms?’

‘By ghosts.’

‘That will need conjury.’

He sat up, speaking more loudly. ‘Conjury is my business. I must call up visions before I can construct a play.’

The pilot looked over his shoulder as though he expected to catch a large theatrical gesture to smile at but saw only the set face of a man who took his work seriously and chose to express himself in metaphor.

Andra grinned quickly at him and said, ‘In all this wreckage there must be a few ghosts on call.’

‘Dirty, stinking ghosts, Artist, crowded, lewd and violent.’ His urgent Christianity spurred him further than was wise. ‘They were evil people.’

‘Nevertheless,’ Lenna said, ‘they were the stuff of history.’

Marin, competent at his work, was also an academically ambitious man; his formal address of Lenna did not indicate respect, only a distancing. With the certainty of the indoctrinated he insisted, ‘They were wicked – they and those like them ruined the world for all who came after. Scholar, they denied history.’

‘Perhaps so,’ she replied equably, ‘but if history is to record the ascent of man it must also recognize the periods of his fall.’ Oh, dear, now we’ll get the Garden of Eden.

He was not such a fool as that and knew he had overplayed dogmatism. He pushed up a smile. ‘In a few minutes, Artist, you will be able to question the ghosts for yourself.’

It was not much of a jest but it served to end discussion. He pulled the wheel hard over and the powercraft swung smoothly past two drearily tumbled steel and concrete monsters. The remains of broken walls that protruded above the water for a forlorn story or two were black with the grime of centuries, pitted with friction and a thousand agents of corrosion; glassless windows gaped.

‘Twenty-three,’ said Marin, gliding them into the shadow of the tower that stood like a sentry on the northwest corner of the Enclave.

The building, Andra judged, was about 100 meters square and the water at this point – he glanced at the pilot’s dashboard – was something more than thirty meters deep so that what remained, with only three fairly whole stories rearing above the water, was a poor fragment of a once colossal structure. Narrow, shattered balconies ran completely around each floor and to one of these was hooked a sort of gangplank descending a few feet to a floating platform. Marin drew the powercraft alongside and grappled on.

‘Best to dress, Artist,’ he suggested as he shrugged into an overall. ‘It is cooler inside.’

‘Thank you.’ Andra pulled on shirt and trousers while Lenna, fully dressed because she thought sunbathing an unproductive and dull pursuit, stepped overside on to the platform which rocked to her weight.

‘That wouldn’t ride out a mild storm,’ Andra observed.

‘The History Department provides a caretaker at each Enclave. The access floats are taken in when need be.’

‘After all this time you still study these ruins?’

‘There’s no end to it. Divers find new and strange things, new study techniques demand constant scrutiny of the artefacts, fresh interpretations demand wholesale re-examination of the buildings.’

He was impressed. ‘I’m told that your work in progress overthrows previous conclusions.’

Suddenly a tutor, she corrected him. ‘Seeks to modify some previous conclusions about social attitudes of the Greenhouse Culture and to suggest that the Sweet/Swill cleavage was less complete than has been assumed.’

‘That sounds the sort of information I need.’

‘For your playscript?’

‘For bridging characters. It would be difficult to present two totally separated strata.’

She said with tutorial orderliness, ‘We must discuss it later,’ and switched to picnic enthusiasm as she started up the gangplank, ‘Come inside, it’s absolutely fascinating.’

It was not a word he would have chosen for the naked concrete of the tiny apartment they entered through the balcony window. Bare rooms always seem small, constricted, but to Andra these were claustrophobic. There were three, each about three meters by two and a half, leading into each other, and two half-sized roomlets at one end. He thought that with some knocking out of walls it would make an overnight flat, a pied-à-terre, but not a place to live in. He hazarded, ‘A two-person flat?’

Behind him Marin laughed without joy. Lenna said, ‘It was intended for a family of four, but there was never enough room and soon no money for building. Seven or eight was common, often more than that.’

‘In here! They’d live like animals!’ The words were shocked out of him.

‘Animals had more space – they were precious. Think of this: there were seventy floors in the completed tower and we estimate that 70,000 people lived in it.’

He stared doubtfully around the box of a room.

‘That meant,’ Lenna said, ‘when you subtract areas for lightwells, liftwells and stairways, less than four square meters of living space for each individual and his furniture.’

Andra could not take it in. He imagined eight beds, with chairs and tables, wardrobes and shelves . . . an airship cabin would afford more space . . . ‘Such poverty!’

Marin spoke like one who sees no need for shock. ‘Throughout history, poverty was the lot of the common man.’

Lenna glanced at him with mild surprise. ‘Yes, we tend to forget that. We see the monuments and forget the millions who starved to raise them.’

Andra shivered, not with cold. ‘At least we have eliminated that from the world.’

‘The interesting statistic,’ she said drily, ‘is the number of millennia it took us to learn how to do so, though it was always easy and we always knew it.’

She led the way from the flat into a dark corridor that ran the length of the building. A window at each extremity gave the only light save at the end where they stood; here a battery-fed standard lamp had been set up to illuminate some thirty meters of the length. By its light Andra saw that the cracked, broken, flaked-away walls had at some stage been painted; faint outlines and fainter suggestions of colour spread over every inch of wall space.

Hesitantly, peering, he asked, ‘Murals?’

Lenna said, ‘Of a kind,’ and Marin, ‘You’ll see.’

She went ahead toward the window at the western end. ‘We have managed to reconstruct a section of the wall decorations by computer-enhanced X-ray examination. Bring the lamp, please, Marin.’

The pilot brought the light down to the last doorway in the corridor, where it sparkled on a dozen meters of extraordinary glitter and confusion.

‘They used paint, charcoal, whitewash, aerosol lacquers and anything that would cling and then spread their designs one atop the others. Creative boredom.’

Indeed so. Andre could recognize nothing entirely, could only perceive hints of design emerging from a chaos of forms and streaks and splotches and dismembered spates of lettering. He studied the lettering, trying to extract words, and could not.

‘Language has changed,’ Lenna reminded him.

He told her irritably, ‘I learned Late Middle English for the reading of Shakespeare originals but I can’t recognize anything here.’

‘Poverty, Andra. Education was one of the luxuries that went into the discard. Most of the late Swill neither wrote nor read. Those who did couldn’t spell.’

The subject common to graffiti the world over appeared again and again in blatant crudity and total lack of draftsmanship, but the finest example, drawn over all the rest and pristine in reproduction, graced the door of the corner flat. In brilliant, impertinent white a huge penis stretched most of the height of the door, balanced on a pair of gargantuan testicles.

‘Strangely,’ Lenna said, ‘we know that to have been a child’s joke. The most extraordinary snippets of information survive. We know quite a lot about the man who lived here.’

‘That he was proud enough to leave this on his door?’

‘We don’t know what he thought. That’s a problem in historical reconstruction, that we know what and usually why but so rarely how the people thought about anything.’

‘Written records,’ he protested.

‘Those aren’t thoughts so much as afterthoughts, and they generally show it.’ She pushed the door open. ‘We’ve tried to reconstruct this flat from scraps of information on a dozen tapes and files, but we still don’t know the important thing about the Kovacs family, how its members thought from moment to moment. We can only extrapolate – meaning guess.’

She urged him gently inside.

His immediate reaction was that nobody in such surroundings could think at all. In the first room were two single beds and between them a roughly carpentered rocking chair; on one side, between the foot of a bed and the end wall, stood a small table which could unfold to some two meters and, leaning behind it, four pews folded flat. The floor was covered with a shiny, patterned material which Andra bent to touch.

‘What is it?’

‘They called it plastic linoleum. We had to manufacture a substitute – it wears quickly.’

Behind him, next to the door, a grey one-and-a-half meter screen filled the available space; below it an array of knobs and terminals was lettered with abbreviations he could not follow.

‘Television?’

‘They called it a triv; it was a general purpose communication center. They hadn’t advanced to crystal web projection. That’s one of the few things we do better than they.’

Marin said sharply, ‘We use everything better. We live better, think better.’

Andra spoke without looking around. ‘Be a good fellow and give your spleen a rest.’

He moved to the next room. Here were two double-tiered bunks with a chair between and footlockers at the ends. On the walls cartoon pictures danced – anthropomorphized cats, dogs, mice and a large, fat-bellied, ineffably good-natured bear.

‘For children?’

‘Surely. Eleven people lived in this flat, most of them children. We suppose they slept two to a bed in here.’

Something essential was missing. ‘Where did they store their clothes?’

‘A short answer might be, what clothes? They had little beyond necessities. Probably they folded them at night and used them as pillows.’

He shivered again, unable to control pity and a creeping, unreasonable shame. At the same time his planning mind was creating a stage set – a full-width apartment with sections of the next one and at the other end the outdoor balcony – sliding walls, fold downs – the whole thing on turnover with the outer wall on the reverse, with crystal web illusion to give length and perspective – lifts, shifts, turntables, scrims, all in constant motion to allow actors access to flats above and below – and all alive with restless, shabby, desperate, pulsating life . . . odor stimulation to provide a discreet hint of animal sweat at moments of crowded energy . . .

The third room was comparative luxury – one double bed, one chair, one small cupboard, a table and, surprisingly, a bookcase.

‘This was the only concession he allowed himself. A private room to run to.’

‘Who?’

‘Kovacs. Billy Kovacs. He was the Tower Boss, a man of great authority, feared and loved.’

Andra knelt to the books. ‘Encyclopedias, dictionaries, an atlas, children’s primers. For teaching his children?’

‘For teaching himself. He had vision of a sort. In an earlier day they might have called him a Renaissance Man.’ Andra pulled at a huge, ancient tome, ‘Don’t. They’re dummies. His own copies were dust long ago – they were old and dated when he owned them.’

The busy internal note-taker muttered to itself, Now there’s a character I could play – gutter visionary – tall, tough, no, shuffling, slightly hunchbacked with raging eyes, no, stop being obvious, file it for later . . .

The two small end rooms were respectively a tiny kitchen and a shower recess with lavatory stool. ‘No laundrapool,’ he commented before the foolishness of that struck him.

Lenna made scrubbing motions. ‘Kitchen sink. Rough soap and muscle power.’

‘I can’t take this in. I want to go outside. I’ll look in again in a day or two.’

Marin said, ‘Try to imagine the smell of eleven grimy bodies, meals cooking and a blocked sewer. The noise of screeching kids and desperate adults bawling at their nerves’ ends.’

Andra went straight out of the place and back to the powercraft. In the density of the vision conjured by his creativity he was sweat-stinking, revolted, need-driven and guilty before the 70,000 ghosts of Tower Twenty-three.

The university had been built 1,000 meters up on the forward slopes of the Dandenongs, its south faces looking out over the foothills where the New City sprawled in smug comfort, over the islands which had been the outskirts of the Old City and, further, over the water which was its grave. Its low buildings camouflaged by trees, the university was nearly invisible by day but now, with the sun westering down to the horizon and searching out window glass, it could be detected in brilliant blazes under the green.

In Lenna’s flat, on the southern rim of the campus, Andra drank her imported coffee – New Guinea Highland, Mutated, very draining on credit – and gazed out over the islands and the bay. After the afternoon calm it was visibly tumultuous, even at this twenty-kilometre remove, grey and streaked and ominous; closer, just outside the panoramic window, branches whipped and shrubs bent before the wind.

He was a Sydney man, new to this southern phenomenon of an evening gale which lashed the sun down into the water before dying away into silent night. ‘Is it regular, every night?’

Lenna, fortyish and lazily plump, was content to take her coffee at ease in a lounger. ‘Quite regular. In winter, longer and colder.’

‘A trend?’

‘Possibly. The meteorologists will not commit themselves. This may be a limited, minor weather cycle but it will take a decade of observation and measurement to be sure.’

‘I saw animals swimming in the bay as we came back. Marin said they were seals.’

She smiled at his unwillingness to ask the obvious question. ‘Yes. They are coming further north as the polar currents edge up the coast.’

‘I’ve read’ – he hesitated with the uncertainty of the amateur before a more precisely trained mind, – ‘I’ve read that the Ice Age could strike very quickly.’

‘In historical terms, that’s true, but quickly to a historian may mean a couple of centuries.’ He looked ridiculously relieved, she thought, as though he had suspected it of waiting to catch him before bedtime. ‘There will probably be a succession of cold snaps – very sudden and very cold, each lasting a decade or so – before the interglacial ends and the ice closes in. There’s little chance that you will see it happen.’

‘I don’t wish to, I like the world as it is.’ But he had been deeply affected by the towers and the sense of an immense past thirty or forty meters below the keel, brought face to face in his creative imagination with the vastness of changes that had metamorphosed a planet as mindlessly as cosmic eruptions destroyed and created stars.

Lenna said, ‘We know this interglacial is approaching its end. The Greenhouse melted the poles and the glaciers, and those won’t reform overnight, but the conditions that will finally recreate them will freeze the bones of the planet long before.’

‘And humanity that has just struggled out of a second Dark Age will have its back to the wall again.’

‘Don’t be dramatic about history. We’re very well equipped to endure a million years of cold. Our ancestors weathered an Ice Age in caves and animal skins, hunting with flint-tipped spears. I’ll be surprised if we don’t do reasonably well with insulation technology and fusion power. Besides, the equatorial zone will almost certainly be ice-free and temperate. An Ice Age is no great tragedy – it is in fact the normal state of the planet. We have knowledge and we have the Forward Planning Centers. We’ll make the change smoothly.’

Outside, the sun vanished and the evening wind slackened perceptibly. The sky darkened. In the foothills, street lights made sudden patterns of habitation.

Andra made a short, trained, dramatic gesture to the scattered tower Enclaves fading into darkness. ‘As I understand it, if I’ve followed the historical line correctly, they knew what was coming to them just as we know what is ahead of us. Yet they did nothing about it.’

‘They fell into destruction because they could do nothing about it; they had started a sequence which had to run its course in unbalancing the climate. Also, they were bound into a web of interlocking systems – finance, democratic government, what they called high-tech, defensive strategies, political bared teeth and maintenance of a razor-edged status quo – which plunged them from crisis to crisis as each solved problem spawned a nest of new ones. There was a tale of a boy who jammed his finger in the leak in the dyke – I think it’s still in kindergarten primers. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries the entire planet stood with its fingers plugging dykes of its own creation until the sea washed over their muddled status quo. Literally.’ She gestured. ‘It’s all there for you to read.’

Andra put down his coffee and crossed the low table (solid ebony, he noted with collector’s envy) where lay the eleven great fat folders titled A Preliminary Survey of Factors Affecting the Collapse of the Greenhouse Culture in Australia.

Preliminary! There must be 5,000 sheets here, a million words. Who could extract dramatic data from such a torrent? In the terms of his research grant he had just one week . . . Wondering how to put this to her without offense, he asked, gaining

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...