HOW DO GODS DIE? AND WHEN THEY DO, WHAT BECOMES of them then?

You might as well ask, how do gods get born? All three questions are, really, the same question. And they all have a common assumption: that humankind can no more live without gods than you can kill yourself by holding your breath.

(Of course, you just may be the kind of arrant rational ist who huffs that modern man has finally freed himself from ancient enslavement to superstition, fantasy, and awe. If so, return this book immediately to its place of purchase for a refund; and, by the by, don’t bother trying to read Shakespeare, Homer, Faulkner, or, for that matter, Dr. Seuss.)

We need gods—Thor or Zeus or Krishna or Jesus or, well, God—not so much to worship or sacrifice to, but because they satisfy our need—distinctive from that of all the other animals—to imagine a meaning, a sense to our lives, to satisfy our hunger to believe that the muck and chaos of daily existence does, after all, tend somewhere. It’s the origin of religion, and also of storytelling—or aren’t they both the same thing? As Voltaire said of God: if he did not exist, it would have been necessary to invent him.

Listen to an expert on the matter.

“There are only two worlds—your world, which is the real world, and other worlds, the fantasy. Worlds like this are worlds of the human imagination: their reality, or lack of reality, is not important. What is important is that they are there. These worlds provide an alternative. Provide an escape. Provide a threat. Provide a dream, and power; provide refuge, and pain. They give your world meaning. They do not exist; and thus they are all that matters. Do you understand?”

The speaker is Titania, the beautiful and dangerous Queen of Faerie, in Neil Gaiman’s graphic novel The Books of Magic, and I don’t know a better summary explanation—from Plato to Sir Philip Sidney to Northrop Frye—of why we need, read, and write stories. Of why we, as a species, are godmakers. And spoken by a goddess in a story.

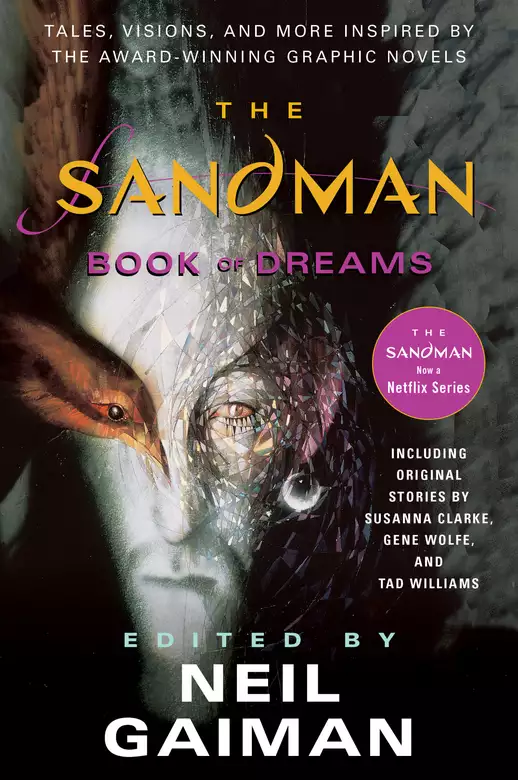

Books of Magic was written while Gaiman was also writing his masterpiece—so far his masterpiece, for God or gods know what he’ll do next—The Sandman. It is a comic book that changes your mind about what comics are and what they can do. It is a serial novel—like those of Dickens and Thackeray—that, by any honest reckoning, is as stunning a piece of storytelling as any “mainstream” (read: academically respectable) fiction produced in the last decade. It is a true invention of an authentic, and richly satisfying, mythology for postmodern, postmythological man: a new way of making gods. And it is the brilliant inspiration for the brilliant stories in this book.

Like most extraordinary things, The Sandman had unextraordinary beginnings (remember that Shakespeare, as far as we can tell, just set out to run a theater, make some cash, and move back to his hick hometown). In 1987, Gaiman was approached by Karen Berger of DC Comics to revive one of the characters from DC’s WWII “golden age.” After some haggling, they decided on “The Sandman.” Now the original Sandman, in the late thirties and forties, was a kind of Batman Lite. Millionaire Wesley Dodds, at night, would put on gas mask, fedora, and cape, hunt down bad guys, and zap them with his gas gun, leaving them to sleep until the cops picked them up the next morning—hardly the stuff of legend.

So what Gaiman did was jettison virtually everything except the title. The Sandman—childhood’s fairy who comes to put you to sleep, the bringer of dreams, the Lord of Dreams, the Prince of Stories—indisputably the stuff of legend.

Between 1988 and 1996, in seventy-five monthly issues, Gaiman crafted an intricate, funny, and profound tale about tales, a story about why there are stories. Dream—or Morpheus, or the Shaper—gaunt, pale, and clad in black, is the central figure. He is not a god; he is older than all gods, and is their cause. He is the human capacity to imagine meaning, to tell stories: an anthropomorphic projection of our thirst for mythology. And as such, he is both greater and less than the humans whose dreams he shapes, but whose thirst, after all, shapes him. As Titania would say, he does not exist; and thus he is all that matters. Do you understand?

Grand enough, you would think, to conceive a narrative whose central character is narrative. Among the few other writers who have dared that much is Joyce, whose Finnegans Wake is essentially one immense dream encompassing all the myths of the race (“wake”—“Dream”: get it?). And, though Gaiman would probably be too modest to invite the comparison, I am convinced that Joyce was much on his mind during the whole process of composition. The first words of the first issue of The Sandman are “Wake up”; the last words of the last major story arc of The Sandman are “Wake up”—the title of the last story arc being, naturally, “The Wake.” (All of Gaiman’s story titles, by the way, are versions of classic stories, from Aeschylus to Ibsen and beyond. A Brit, raised on British crosswords, he can’t resist playing hide-and-seek with the reader—rather like Joyce.)

Grand enough, that. But having invented Dream, the personified human urge to make meaning, he went on to invent Dream’s family, and that invention is absolutely original and, to paraphrase what Prince Hal says of Falstaff, witty in itself and the cause of wit in other men.

The family is called the Endless, seven siblings, in order of age—“Birth,” we’ll see, is not an appropriate term—Destiny, Death, Dream, Destruction, Desire, Despair, and Delirium (whose name used to be Delight). They are the Endless because they are states of human consciousness itself, and cannot cease to exist until thought itself ceases to exist; they were not “born” because, like consciousness, nothing can be imagined before them: the Upanishads, earliest and most subtle of theologies, have a deal to say on this matter.

To be conscious at all is to be conscious of time, and of time’s arrow: of destiny. And to know that is to know that time must have a stop: to imagine death. Faced with the certainty of death, we dream, imagine paradises where it might not be so: “Death is the mother of beauty,” wrote Wallace Stevens. And all dreams, all myths, all the structures we throw up between ourselves and chaos, just because they are built things, must inevitably be destroyed. And we turn, desperate in our loss, to the perishable but delicious joy of the moment: we desire. All desire is, of course, the hope for a fulfillment impossible in the very nature of things, a boundless delight; so to desire is always already to despair, to realize that the wished-for delight is only, after all, the delirium of our mortal self-delusion that the world is large enough to fit the mind. And so we return to new stories—to dreams.

Now that’s an overschematic version of the lineage of the Endless, almost a Medieval-style allegorization. For they’re also real characters: as real as the humans with whom they are constantly interacting throughout The Sandman. Destiny is a monastic, hooded figure, almost without affect. Death—Gaiman’s brilliant idea—is a heartbreakingly beautiful, witty young woman. Dream—is Dream, somber, a tad pretentious, and a tad neurotic. Destruction is a red-haired giant who loves to laugh and talks like a stage Irishman. Desire—another brilliant stroke—is androgynous, as sexy and as threatening as a Nagel dominatrix; and Despair, his/her twin, is a squat, fat, preternaturally ugly naked hag. Delirium, fittingly for her name, is almost never drawn the same way: all we can tell for sure is that she is a young girl, with multicolored or no hair, dressed in shreds and speaking in non sequiturs that sometimes achieve the surreal antiwisdom of, say, Rimbaud.

Nevertheless: the Endless are an allegory, and a splendid one, of the nature of consciousness, of being-in-the-world. And it can’t be emphasized too much that these more-than, less-than gods matter only because of the everyday people with whose lives and passions they interact. The Sandman mythology, in other words, brings us full circle from all classical religions. “In the beginning God made man?” Quite—and quite precisely—the reverse.

And Dream, the Lord of Storytelling, is at the center of it all.

We begin and end with stories because we are the storytelling animal. The Sandman is at one with Finnegans Wake, and also with Nietzsche, C. G. Jung, and Joseph Campbell in insisting that all gods, all heroes and mythologies are the shadow-play of the human drama. The concept of the Endless—and particularly of Dream—is a splendid “machine for storytelling” (a phrase Gaiman is fond of). Characters from the limitless ocean of myth, and characters from the so-called “real” world—that’s you and I when we’re not dreaming—can mingle and interact in its universe: quite as they mingle and interact in you and me when we are dreaming. It’s often been said by literary critics that our age is impoverished by its inability to believe in anything save the cold equations of science. (Hence Destruction, fourth of the siblings, left the Endless in the seventeenth century—the onset of the Age of Reason.) But our strongest writers, Gaiman included, have always found ways of reviving the vitality of the myths, even on the basis of their unreality. Credo, quia impossibile est, wrote Tertullian in the third century A.D., about the Christian mystery: “I believe it because it is impossible.” Good theology, maybe; excellent theory of fiction, absolutely.

Now that The Sandman is over, and its creator has moved on, it continues to serve as a machine for storytelling. DC Comics provides The Dreaming, a series by various hands using the assumptions and the characters invented in The Sandman. And the volume you hold now, by gifted “mainstream” (i.e. non-comic book) writers, all of them expanding and elaborating the Sandman mythos, is perhaps only the first, rich fruit of Gaiman’s new technique for godmaking.

De te fabula, runs the Latin tag: the story, whatever story, is always about you. That’s the ancient wisdom The Sandman makes new: it’s why, finally, we read at all. It is—and I know no higher praise—another realization of Wallace Stevens’s sublime vision of fiction in his great poem, “Esthétique du Mal”:

“And out of what one sees and hears and out

Of what one feels, who could have thought to make

So many selves, so many sensuous worlds,

As if the air, the mid-day air, was swarming

With the metaphysical changes that occur

Merely in living as and where we live.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved