The night before I returned to All Hallows I dreamed I was walking barefoot along the attic corridor. As I passed the fourth door, I became aware of little fires burning in that dark room: on the rug, in the curtains and a dozen other places. I began to run, but the further I ran, the further the corridor stretched ahead of me and the more the fires burned, and I knew that I would never reach the end. There was no escape.

My wife woke me; a hand on my shoulder. ‘Lewis! Wake up! You’re having one of your nightmares.’

It took me a moment to bring myself back to the present: to our warm, untidy bedroom, pillows, a duvet; a wine glass on the bedside table; the dog snoring on his rug in the window bay. The room was dark, the city beyond still sleeping.

‘Sorry,’ I whispered. ‘Sorry to wake you,’ and I kissed my wife’s hand and slid out of bed and went downstairs to drink a glass of water in the kitchen.

It was 4 a.m. The dying hour. I sat at the table, moved aside our youngest son’s homework, and picked up the auction house catalogue that I’d left lying face-down on the table next to the fruit bowl.

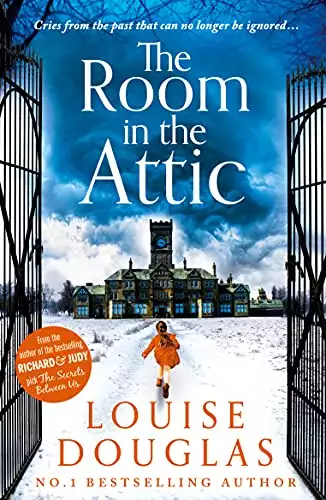

I turned it over. The cover headline read: ‘Rare Redevelopment Opportunity’. Beneath it, the picture of a derelict building was captioned: ‘All Hallows. Grade II listed Victorian asylum/boarding school, outbuildings, 50 acres of walled grounds. Prime countryside location.’

There it was, in full colour: the same long, forbidding building with the bell tower at its centre that I revisited in my nightmares. If I looked hard enough, I could almost see through the windows to the pupils sitting at their desks in the classrooms: those ranks of boys in their brown sweaters and trousers, with identical close-shaven haircuts. I could almost smell the dust burning in the elbows of the big old radiators, hear the relentless ticking of the clocks on the walls. And there, outside, were young boys with their bony knees and striped socks, shivering as they grouped on the rugby field; the padded bumpers used to practise tackles laid out on the grass; the swagger of the sports master with his great, muscly thighs. ‘Three Rolls’, we used to call him because he walked as if he was carrying three rolls of wallpaper under each arm.

The auction had taken place a fortnight earlier, the building sold to clients of the firm of architects for whom I worked. If they’d asked my advice before the sale, I’d have told them not to buy it, but by the time the catalogue reached my desk, the paperwork had been signed, the deal was done.

I dropped my head into my hands.

I did not want to have to return to All Hallows. What I wanted was to speak to Isak, to hear his voice, and be rallied out of my anxiety by his dry humour. I picked up my phone and was on the point of calling him, but then I heard my mother whisper in my ear: Lewis, don’t. It’s not fair to disturb him, not at this hour!

I put down the phone, grabbed my coat and went into the garden to wait for the sunrise.

The All Hallows site had been purchased by an American company that specialised in converting abandoned European country piles into luxury living accommodation. My employers, Redcliffe Architects, had already collaborated with them on a former tuberculosis sanatorium in Switzerland and a dilapidated château in the Loire Valley, both lucrative projects. Everyone at Redcliffe knew we’d be front runners for the design work at All Hallows if we submitted a half-decent proposal.

The chief partner, Mo Masud, asked me to go to Dartmoor to take some pictures and scope out the site. It wasn’t an unusual request and normally I enjoyed nothing more than poking around historic edifices, imagining how they might be brought back to life. I was Mo’s right-hand man. It was my job to go. Still, I put off the mission for as long as I could, hoping something might happen to prevent me from returning to my former school. Deep down, I knew the last-minute reprieve I prayed for wasn’t going to come. No matter how I tried to put the name All Hallows and all that it represented out of my mind, like shame it clung to me. Day by day the sense of encroaching dread increased and none of the usual distractions worked. I drank on school nights. I got up stupidly early to run for miles. My wife kept asking what was wrong. I couldn’t tell her. It wasn’t that I didn’t trust her, it was simply that I did not have the vocabulary to explain what it was that was eating at me.

I couldn’t avoid All Hallows for ever. The name popped up in the headings of emails and messages at work. A file was opened in the Tenders Pending folder and draft graphics of marketing flags saying: ‘Exclusive homes for sale’ appeared on the printer. Mo told me the Americans had asked for a meeting the following week. We needed the information. We needed it now.

The day I drove to Dartmoor was a typical early autumn day: the sky moody; a sullen rain falling. As I passed the once-noble sculpture of the giant withy man at the side of the M5 in Somerset, I remembered how, as we drove this same motorway more than three decades earlier, Mum used to put on a Now That’s What I Call Music! cassette to keep me and my sister, Isobel, entertained, and we’d all sing along. Mum had a friend who owned a static caravan on a site outside Newquay. We used to spend our summer holidays there, Isobel, Mum and I, bodyboarding, picnicking on the beach, sitting round campfires on chilly evenings, listening to the waves crashing onto the sand. Dad never came with us. Isobel and I used to feel sorry for him, all alone at home working while we were having fun, but Mum said he preferred it that way.

The reed beds that used to surround the withy man were gone now and he was dwarfed by development. A melancholy descended on me as I passed him, poor fading thing. I put some of Isak’s music on, turned the volume up loud to try to drown out the memories of the boy I used to be.

The journey from Bristol that day was straightforward, but once on Dartmoor I struggled to find the route back to my old school amongst the tangle of lanes. The landmarks I thought I recognised – stone stacks, brooks and copses – turned out to be red herrings. Soon, I was disorientated and I felt the old anxiety lurking around me, a creeping, bony-fingered thing.

I bumped the VW along rutted old lanes that went nowhere and carried out harried, nine-point turns in muddy gateways, beady-eyed sheep staring at me while their jaws rotated like teenagers chewing gum. There was no signal for the maps app on my phone. If the developers decided to go ahead with this project, access would be a nightmare. These ancient country byways had not been designed to cope with flatbed lorries weighed down by materials. A steady rain fell now, dulling the colours and blurring the verges and the drystone walls. It felt as if hours had passed before, at last, I found the turning to All Hallows at the end of a narrow, unkempt road. I followed the track and the Gothic gates loomed over the entrance.

This was it. I was here.

I left the car by the gates, turned up the collar of my coat and stepped into the abandoned grounds of All Hallows, built in 1802 as a lunatic asylum and refashioned a hundred and fifty years later as a boarding school for boys.

What was left of the place was quietly falling down inside a thick wall originally built to keep the former asylum inmates inside. Large stretches of the wall were hidden behind the overhanging branches of grand old beech trees and beneath swathes of brambles that had grown over and around it. I took some photographs, a small video; made some voice notes. There was a rustle in the undergrowth. A squirrel darted out and ran across the lawn. A crow cawed and I jumped.

Grow a backbone, Tyler, I told myself and I heard, back through the years, the voice of one of the masters barking at me, telling me to stand up straight, stop slouching, walk like a man! I recalled Isak’s quiet grimace of camaraderie and I smiled to myself. He was the best friend I ever had.

The rain was relentless; puddling the ground; dripping through the trees.

I walked forward, taking photographs with my phone.

The main building still stood grand and bullish even though its disintegration was clear. The clock tower at the centre of the façade was intact, along with most of the buildings on either side, but both recumbent stone lions on the pedestals at the foot of the steps were damaged, there were holes in the steeply sloping roof and chunks missing from the walls. Lichen and weeds had taken hold and birds had nested in the cracks in the masonry. Guttering hung from beneath the roof edges, drawing sharp diagonal lines. The west wing, where the fire had caused most damage, had never been repaired and was slumped like an old drunk crouching on one knee. I walked around that part of the school, trying to see through cracked and smoke-darkened windows.

Random memories flashed into my mind: Isak running across the grounds, his legs mud-spattered, his trainers soaked, elbows poking out and his orange hair sticking to his head, one of a long line of boys doing cross-country in the rain; Isak in our bedroom, sitting on the sill with his legs dangling out of the window, blowing smoke rings into the sky. He taking my hand after I’d been hit with the ruler, putting his cold flannel on the palm to soothe the burning; the two of us bound in a friendship so intense that I never felt quite myself if Isak wasn’t with me.

I was twitchy. Overtired, overcaffeinated, overwrought. I kept seeing things that weren’t there. What looked like a body was an old piece of plastic sheeting with puddles forming in the dips of its creases. What I first saw as a gravestone planted in the courtyard turned out to be an abandoned fridge.

‘Stupid,’ I muttered to myself, ‘don’t be so stupid!’

But the anxieties were multiplying. Looking up, I saw something that might have been a face staring from a cobwebbed window. There were movements in the shadows, footsteps behind me, the sound of a child’s laughter, the smell of smoke. I pressed the camera button over and over, taking as many pictures as I could as quickly as I could. I paused to flick through those I’d taken. They all showed the main building and its surrounding architecture. But there were other structures: the old stables; the caretaker’s cottage; the lodge; the chapel. There had been an outdoor swimming pool, the lake with the folly on its overgrown island. We’d need a record of these features too.

The rain was falling more heavily now.

I headed towards the chapel. I didn’t want to get too close. When I was near enough to zoom in for a photograph, I did so. Then I walked to the approximate middle of the grounds and I set the camera to make a panoramic video, and slowly rotated through 360 degrees, holding the device at right angles to my body. I took one clockwise and one anticlockwise, then tucked the phone inside my coat so I could look at the screen without it getting soaked. There was something odd about the second panorama. A woman appeared three times in the image, once at a distance, as if she was standing waist-deep in the lake. Then again, closer. The third time she was almost right in front of me – right behind where I was standing now.

I turned sharply. Nobody was there.

I looked back to the screen but the phone had turned itself off. The battery must be dead. Only it couldn’t be. I’d had it charging in the car all the way down. I shook the phone in frustration. Pressed the ‘on’ button. Nothing happened.

‘Come on,’ I muttered, ‘come on!’ but the device would not respond.

I put it in my pocket, looked up. A woman, the same woman who was in the panorama, was standing amongst the trees at the edge of the lake, hands at her side. Her long, dark hair was dripping, her dress, pulled low by the weight of the stones in its pockets, was soaked and her eyes were fixed on me as if she recognised me.

I knew her too.

I turned and ran back around the building, stumbling over roots and fallen brickwork. I reached the car, climbed inside and locked the doors. For a few seconds I sat with my eyes tightly shut, trying to control my breathing and compose myself. I could not afford to faint. I took out my phone, fumbling as I tried to plug it in to the charger but my fingers were clumsy and I dropped it between the seat and the door.

‘OK,’ I told myself. ‘OK, Lewis, stay calm. All you need to do is drive away. Start the car. Start the bloody car!’

My hands were trembling so badly that it took several attempts to slot the key into the ignition. I glimpsed a movement through the window at my side and saw the woman walking between the gates and heading towards me.

‘Oh God, no!’

I jiggled the steering wheel and the lock at last disengaged, the car juddered into life and I drove down the track, skidding and skittering, going too fast, desperate to be away. I was back on the A38 before I’d calmed down enough to try to rationalise what I’d experienced and to chastise myself for letting my nerves so completely get the better of me.

I stopped at the services.

I looked at the photographs on my phone, scrolling through them, searching for signs of the woman. I couldn’t find her. And although the first panorama video I’d made had worked well, the second was gone. I looked everywhere, even in the deleted folder, but it had vanished. I had no proof that the woman was ever there.

But I knew. I knew who she was and why she lingered. It was because of Isak and me, and everything that happened in those last months of 1993 when I was thirteen and Isak was fourteen and we shared the same bedroom at All Hallows. The time that began at the very point when my whole world had fallen apart.

Nurse Emma Everdeen only knew what she’d been told, which was that around lunchtime on the previous day, the crew of a local fishing vessel, the March Winds, had spotted a lugger bobbing, apparently empty, amongst the waves about a mile off the Devon coast. When they went to investigate, leaning over the side of the trawler, they saw a woman and a child lying together in the bottom of the smaller boat, seawater swilling over and around them and both apparently lifeless; most likely drowned. The fishermen hooked the lugger and drew it close, tied it to their own craft and towed it into Dartmouth harbour. There, they climbed down the harbour steps where the lugger was being bumped against the wall by the incoming tide, and lifted the woman and the child clear. They were found to be alive, but barely: cold as ice, their clothes drenched. The woman, who was wearing a fine day dress made of muslin and rose-coloured twill, had a deep cut to her upper arm and it appeared she had attempted to tie her own tourniquet from a strip of fabric torn from the skirt of her dress and bound over the sleeve. She was still wearing her jewellery. The fishermen had made much of the fact that they were honest man who had not removed so much as a ring from her finger.

The pair were taken to the local doctor’s house. A fire was lit and they were laid beside it, their wet clothes removed and replacements found. The jewellery was dried, a list made, and it was placed in a small velvet bag. The woman’s wound was attended to and dressed and she and the child, assumed to be her daughter, were warmed by the flames and a tot of warm brandy poured into their mouths. The child woke and was so distressed that the doctor immediately treated her with a sedative. The woman remained asleep. When she failed to rouse, the doctor telephoned All Hallows, reasoning that the staff at the asylum, with their resources, would be in a better position to help the unfortunate pair. All Hallows superintendent, Mr Francis Pincher, discussed the matter with the general manager, Mr Stanford Uxbridge, and they agreed that the patients should be brought there, it being undoubtedly the best place for them.

Mr Pincher wasn’t acting from altruism. He was a businessman whose priority was money and, having been made aware of the quality of the woman’s clothing and jewellery, it was evident that money was connected to these patients. All Hallows’ buildings were more than a hundred years old, large, chilly and costly in terms of maintenance. The asylum was overcrowded, there being more patients in need than available accommodation for them. Food and fuel and constant stocks of bedding, furniture and other materials had to be purchased. And there were staff wages to pay; not only the nursing and medical staff but also cooks, domestics, gardeners and caretakers, the groom, the coachman, the chaplain’s stipend, the gravedigger when called for, the mole-trapper, the deliverymen and so on. Finally, on top of all this expenditure, the shareholders expected All Hallows to make a profit.

It was no secret that standards had begun to slip at the asylum. Staff were hard to come by in such a remote area. When there were not enough staff to supervise the patients, the patients had to be locked up, or restrained, for their own safety. Hardly a day went by without a nurse blowing the emergency whistle hung round her neck after one of the charges, frustrated at being confined, went berserk, necessitating the attention of the orderlies, who, if necessary, would beat him or her with their truncheons until the patient was quiet again.

The sale of just one or two pieces of the woman’s fine jewellery would more than cover any costs incurred in the treatment of her and the child, leaving extra for the employment of additional staff, or to upgrade the facilities, or to provide a shareholders’ bonus. And also, the superintendent reasoned, the mystery attached to the pair, and the solving of that mystery would give him a fine story to tell and could only benefit the reputation of All Hallows and spread the institution’s name far and wide.

For now the imperative was to send the horse-drawn ambulance to bring the patients from Dartmouth to All Hallows. Mr Pincher sent his longest-serving nurse to collect them and accompany them on the return journey. Her name was Emma Everdeen and she was almost seventy years old. This would be the first time she had left the hospital boundaries for more than a year.

I was thirteen and three-quarters when my father and stepmother sent me to All Hallows boarding school on Dartmoor.

My mother had died eighteen months earlier and I was angry and unhappy and difficult. My stepmother said I was a delinquent but I wasn’t: I was a Goth. I had no idea why she couldn’t tell the difference.

I had been a Goth since soon after I started secondary school, a modern comprehensive in Bristol where, to begin with, everyone, even the teachers, called me ‘Wingnut’ which had been my nickname since primary school because of my sticking-out ears. The Goth thing started because my best friend, Jesse, grew his hair to impress a Goth girl and I grew mine to keep him company. As soon as my hair was long enough to cover my ears, miraculously everyone stopped calling me Wingnut, which was when I decided I’d be a Goth too. Added bonuses were that the make-up Jesse, I and a growing band of friends wore, hid my spots, and the ripped jeans, boots and baggy coat that were my out-of-school uniform disguised the fact that I was small and skinny and at the same time made me look less so.

The Goths at school looked sullen but were a friendly group. The bigger kids looked out for the littler ones. It was like becoming part of a ready-made family.

Mum never discouraged me. She liked my friends and they liked her. After school and in the holidays, when Dad wasn’t around, everyone used to congregate at our house. We’d spill out into the back garden, which was long and thin, and we’d take off our vampire coats and Dr Martens boots and play Swingball barefoot on the scrubby old lawn and drink chocolate milk. Our lovely old dog, Polly, would limp out to join us and my friends would compete for her affection, she being the best Labrador-cross in the world. Also, one of the oldest. She was three months older than me – Mum and Dad had bought my older sister, Isobel, the puppy to stop her being jealous when I was born – and she only had three legs. Polly, I mean, only had three legs. She lost the other one after she was hit by a car when she ran out into the road chasing a motorbike when she was young.

Polly died in her sleep in her basket in the corner of my bedroom the week before Mum had her accident. I was nowhere near coming to terms with the loss of Polly when Mum went too. It was like being hit in the face with a sledgehammer twice. I couldn’t understand how it was that my wonderful life could have changed so completely, so quickly, without me having changed at all. It made me realise I had no control over anything. I was like the homeless man who sat on the pavement outside the greengrocer’s, wrapped in his old sleeping bag even in summer. Mum used to buy him a sandwich and coffee and suggest ways in which he could ‘move forward’ with his life and he always said: ‘The universes are aligned against me, so what’s the point?’ Mum told me universes were inanimate and could therefore neither be ‘for’ nor ‘against’ anyone but this was a bit hypocritical because she also believed very strongly in the stars.