- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

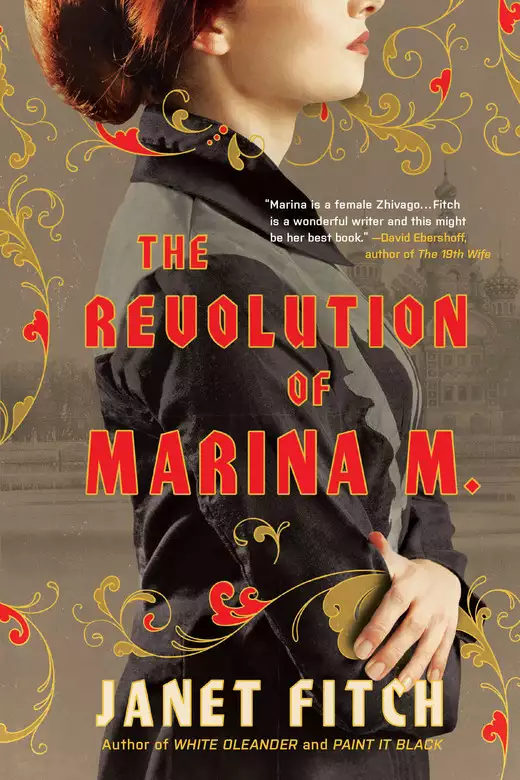

From the mega-bestselling author of White Oleander and Paint It Black, a sweeping historical saga of the Russian Revolution, as seen through the eyes of one young woman

St. Petersburg, New Year's Eve, 1916. Marina Makarova is a young woman of privilege who aches to break free of the constraints of her genteel life, a life about to be violently upended by the vast forces of history. Swept up on these tides, Marina will join the marches for workers' rights, fall in love with a radical young poet, and betray everything she holds dear, before being betrayed in turn.

As her country goes through almost unimaginable upheaval, Marina's own coming-of-age unfolds, marked by deep passion and devastating loss, and the private heroism of an ordinary woman living through extraordinary times. This is the epic, mesmerizing story of one indomitable woman's journey through some of the most dramatic events of the last century.

Release date: November 6, 2018

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 816

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Podcasts

Author updates

The Revolution of Marina M.

Janet Fitch

MIDNIGHT, NEW YEAR’S EVE, three young witches gathered in the city that was once St. Petersburg. Though that silver sound, Petersburg, had been erased, and how oddly the new one struck our ears: Petrograd. A sound like bronze. Like horseshoes on stone, hammer on anvil, thunder in the name—Petrograd. No longer Petersburg of the bells and water, that city of mirrors, of transparent twilights, Tchaikovsky ballets, and Pushkin’s genius. Its name had been changed by war—Petersburg was thought too German, though the name is Dutch.

Petrograd. The sound is bronze, and this is a story of bronze.

That night, the cusp of the New Year, 1916, we three prepared to conjure the future in the nursery of a grand flat on Furshtatskaya Street. From down the hall, the sounds of a large New Year’s Eve soiree filtered under the door—scraps of music, women’s high laughter, the scent of roasted goose and Christmas pine. Behind us, my younger brother, Seryozha, sketched in the window seat as we girls prepared the basin and the candle.

Below in the street, harness bells announced sleighs busying themselves transporting guests to parties all along the snow-filled parkway. But in the warm room before the tiled stove, we breathlessly circled the basin we’d placed on the old scarred nursery table, its weathered apron ringed with painted sailor boys, waiting for midnight. I stroked the worn tabletop where I’d learned to make my letters, those shaky As and Бs and Bs, outlined the spot where my brother Volodya gouged his initials into the tabletop. Volodya, now fighting in the snows of Bohemia, an officer of cavalry. And we brand-new women in evening gowns waited to see our fortunes. I close my eyes and breathe in the scent of that long-ago room, beeswax and my mother’s perfume, which I’d dabbed on my breasts. I still see Varvara in her ill-fitting black taffeta gown, and Mina in a homemade dress of light-blue velvet, and myself in russet silk with an olive overlay, my hair piled on my head, sculpted that morning by M. Laruelle in the Nevsky Passazh. My artistic brother, with his long poet’s locks, sported a Russian blouse and full trousers stuck into soft boots in shocking defiance of wartime custom, which dictates that even noncombatants strive for a military air.

I was a month shy of sixteen, the same age as the century, my brother one year younger. Waiting for midnight, our three heads converged over the basin of water: Varvara’s cropped locks, the dusty blue-black of a crow; Mina’s, ash blond as Finnish birch, woven into that old-fashioned braided crown she couldn’t be persuaded to abandon; and I, with hair the red of young foxes crossing a field of snow. Waiting to see our fortunes. Kem byt’? indeed.

A sun, a seal, a wedding ring.

A house, a plow, a prison cell.

It seems like a scene in a glass globe to me now. I want to turn it over and set the snow to swirling. I want to shout to my young self, Stop! Don’t be in such a hurry to peel back the petals of the future. It will be here soon enough, and it won’t be quite the bloom you expect. Just stay there, in that precious moment, at the hinge of time…but I was in love with the Future, in love with the idea of Fate. There’s nothing more romantic to the young—until its dogs sink their teeth into your calf and pull you to the ground.

On St. Basil’s Eve, we cast the wax in water.

And the country too had poured its wax

In the year of the 9 and the 6.

What sign did I hope to receive that night? The laurel crown, the lyre? Or perhaps some evidence of grand passion—some ardent Pushkin or soulful Blok. Or maybe a boy I already knew—Danya from dancing class, Stiva with whom I’d skated in the park the day before and dazzled with my spins and reckless arabesques. Or perhaps even an officer like the ones who lingered before the gates of our school in the afternoons, courting the senior girls. I see her there, staring impatiently into the candle flame, a girl both brash and shy, awkward and feigning sophistication in hopes of being thought mysterious, so that people would long to discover her secrets. I want her to stay in that moment before the world changed, before the wax was poured, and the future assembled like brilliant horses loading into a starting gate. Wait!

My younger self looks up. She senses me there in the room, a vague but troubling presence, I swear she catches a glimpse of me in the window’s reflection—the woman from the future, neither young nor old, bathed in grief and compromise, wearing her own two eyes. A shudder passes through her like a draft.

Midnight arrived in a clangor of bells from all the nearby churches, Preobrazhenskaya, St. Panteleimon, the Church of the Spilled Blood, bells echoing throughout the city, escorting in the New Year. Solemnly I handed the candle to Mina, who pushed her spectacles up on her nose and bent her blond head over the basin. Precise as the scientist she was, she dripped the wax onto the water as I prayed for a good omen. The lozenges of wax spun, adhered, linked together into a turning shape, the water trembling, limpid in candlelight. To my grave disappointment, I detected no laurel wreath, no lyre. No couples kissing, no linked wedding rings.

Varvara squinted, cocking her head this way and that. “A boot?”

Seryozha peered over our shoulders. Curiosity had gotten the better of him. He pointed with a long, graphite-dark finger. “It’s a ship. Don’t you see—the hull, the sails?”

A ship was good—travel, adventure! Maybe I’d become an adventurer and cross the South Seas, like Stevenson…though the German blockade sat firmly between me and the immediate realization of such a heady destiny. Or perhaps it was a metaphor for another kind of journey. Could not love be seen as a journey? Or the route to fame and glory? Try as I might to tease out the meaning, it never would have occurred to me its final dimensions, the scope, the nature of the journey.

Varvara poured for Mina. The wax coalesced—a cloud, a sleigh? We concurred—a key! She beamed. Surely she would unlock the secrets of the world, the next Mendeleev or Madame Curie. No one considered that a key might lock as well as unlock.

And Varvara? The swirling dollops resolved themselves into—a broom. We shouted with laughter. Our radical, feminist, reader of Kollontai, of Marx and Engels, Rousseau and Robespierre—a housewife! “Maybe it’s a torch,” she said sulkily.

“Maybe it’s your new form of transport,” Seryozha quipped, settling himself back into the window seat.

She sieved the little wax droplets from the water and crushed them together, threw the lump in the trash, wiped her wet hands on a towel. “I’m not playing this stupid game anymore.”

Seryozha refused his turn, pretending it was a silly girl’s pastime, though I knew he was more superstitious than anyone. And behind us, in the red corner, the icon of the Virgin of Tikhvin gazed down, her expression the saddest, the most tender I had ever seen. She knew it all already. The ship, the key, the broom.

With no more future to explore, and Varvara sulky with her news, we abandoned the peace and timelessness of the nursery to rejoin the current era out celebrating in the salon. No one had noticed our absence but Mother, who glared briefly but sharply in our direction, irritated that we’d missed the New Year’s toasts. Vera Borisovna Makarova wore a Fortuny gown with Grecian pleats and a jeweled collar, a Petersburg beauty with her prematurely silver hair and pale blue eyes. Mother took her social responsibilities seriously, orchestrating her parties like a dancing master, quick to spot a group flagging, a woman standing uncomfortably alone, men speaking too long among themselves. Our New Year’s Eve party famously brought together my father’s jurists and journalists, diplomats and liberal industrialists with Mother’s painters and poets, mystics and stylish mavens—in short, the cream of the Petrograd intelligentsia. Did this impress me? The British consul flirting with the wife of the editor of the Petrogradsky Echo? The decadent poet Zinaida Gippius in harem pants taking another glass of champagne from Basya’s tray? It was our life. I didn’t realize how fragile such seemingly solid things could be, how soon they could vanish.

In the dining room, we picked at the remains of the feast laid out on yards of white damask—roast goose with lingonberries, salad Olivier, smoked salmon and sturgeon and sea bass, the mushrooms we’d picked that autumn. Blini with sour cream and caviar. No boeuf Wellington as in past years, boeuf having disappeared with the war. But Vaula’s Napoleons glistened, and the Christmas tree exuded its resin, which blended with the smell of Father’s cherry tobacco, imported all the way from London by friends in the British consulate. Yes, there he was, in the vestibule, lounging in his tailcoat, his shirt a brilliant white. Handsome, clever Father. I could tell he had just said something witty by the way his dimples peeked out from his neat reddish-brown beard. And beside him on the table lay his gift to me in honor of my upcoming birthday—my first book of verse. I’d been obsessively arranging and rearranging the small volumes all day around a giant bouquet of white lilacs. I admired the aqua cover embossed in gold: This Transparent Twilight, by Marina Dmitrievna Makarova. It would be a parting gift for each guest. The poet Konstantin Balmont, a friend of my mother’s, had even reviewed it in the Echo, calling it “charming, promising great things to come.” I’d had more sensuous, grown-up poems I’d wanted to include, but Father had vetoed them. “What do you know about passion, you silly duck?”

Still, I agonized when anyone picked up a volume and paged through it. What would they think? Would they understand, or treat it as a joke? By tomorrow, people would be reading it, and around the dinner tables, they’d be saying, That Makarov girl, she really has something. Or That Makarov girl, what an embarrassment. Well, at least her father loves her. I tried to remember the ship, the South Seas, and told myself—who cared what a bunch of my parents’ friends thought? Varvara took glasses of champagne off Basya’s tray and handed them to us, “To Marina’s book and all the tomorrows.” She drank hers down as if it were kvas and put it back on the tray. Our maid scowled, already unhappy in the evening uniform she loathed, especially the little ruffled cap. She’d been on her feet since seven that morning.

The champagne added to my excitement. My father cast me an affectionate glance, and a sharp one of disapproval for my brother. He’d so wanted Seryozha in school uniform, hair shorn, looking like a seryozny chelovek—a serious person—but Mother had defended him, her favorite. “One night. What harm could there be in letting him dress as he likes?”

In the big salon, couples whirled and jewels flashed, though not so garishly as in the years before the war. In the far corner, the small orchestra sweated through a mazurka, and people who shouldn’t have, danced. A red-faced man lowered himself into a chair. My head swam in the heady mix of perfume, sweat, and tobacco. And now, a slightly fetid sweetness like rotting flowers announced the approach of Vsevolod Nikolaevich, our mother’s spiritual master, pale and boneless as a large mushroom. He took my hand in his powdery soft one. “Marina Dmitrievna, my congratulations on your book. We’re all so very proud.” He kissed it formally—the lips stopping just short of the flesh. He dismissed my friends at a glance—Varvara in her purple-black, Mina in homemade blue—as people of no consequence, and zeroed in on my brother. “Sergei Dmitrievich. So good to see you again.” He proffered his flabby hand, but my brother anticipated the gesture and hid his own behind his back, nodding instead. Unflappable, Vsevolod smiled, but took the hint and retreated.

Once the mystic was out of sight, Seryozha extended his hand floppily, making his mouth soft and drooly. “Wishing you all the best!” he snuffled, then took his own hand and kissed it noisily. It took many minutes for us to catch our breaths as he went through his Master Vsevolod routine, ending by reaching into a bouquet, plucking a lilac, and munching it.

I swayed hopefully to the music, my head bubbling like the champagne—French champagne, too, its presence in wartime negotiated months in advance—and watched the sea of dancers launch into a foxtrot. I was an excellent dancer, and hated to wait out a single number. Having removed her glasses, Mina squinted at what must have been a blur of motion and color while Varvara examined the Turkish pants and turbans of the more fashionable women with a smirk both ironic and envious. One of the British aides had just smiled at me over his partner’s shoulder, when a vision beyond anything I could have wished for up in the nursery swam into view: a trim, moustached officer with uptilted blue eyes, his chestnut hair cropped close, lips made for smiling. Heat flashed through me as if I’d just downed a tumbler of vodka. Kolya Shurov was back from the front.

Was he the most handsome man in the room? Not at all. Half these men were better looking than he was. And yet, women were already smiling at him, adjusting their clothing, as if it were suddenly too tight or insecurely fastened.

Kolya was coming this way. Mother was leading him to us!

“Enfants, regardez qui en est venu!” she said, glowing with pleasure. She always loved him—well, who didn’t? Look who’s here! “Just in time for New Year’s.”

He leaned in and kissed my cheeks formally, three times—for Father, Son, and Holy Ghost—and I caught a whiff of his cologne, Floris Limes, and the cigar he’d been smoking. He held me out at arm’s length to examine me, beaming as if I were a creature of his own invention. The blood tingled in my cheeks under his scrutiny, the warmth of his hands through the thin sleeves of my dress. My face flushed. I could hardly think for the pounding in my chest. “Look how elegant you’ve become, Marina Dmitrievna. Where’s the skinny girl disappearing around corners, braids flying out behind her?”

“She disappeared. Around a corner,” I said, an attempt at wit. I wanted him to know that things had changed since he’d last seen me. I was a woman now—a person of substance and accomplishment. He couldn’t treat me like that girl he used to whirl around by an arm and a leg. “It’s been a while, Kolya.”

“How I’ve missed beautiful women.” He sighed and smiled at Mina—she was blushing like a peony. My God, he would flirt with a post!

Now he embraced my brother, clapping him on the back, ruffling his hair. “And how is our young Repin? Nice shirt, by the way.” That shirt, which Seryozha had sewed himself and which my father had mocked. Kolya took him by the shoulder, turned him this way and that, examining the needlework. “I should have some made up just like it.” Who didn’t love Kolya? None of Volodya’s other friends ever paid us the least attention, but Kolya wanted everyone to be happy. No one escaped the wide embrace of his nature. “Are you still waiting for me, Marina?” he said into my ear. “I’m going to come and carry you off. I told you I would.” When I was a scabby-kneed six-year-old and he a worldly man of twelve.

Was this the ship, then, the wax sails? Kolya Shurov? Blood roared in my ears. The intensity of my desire frightened me, I wanted to put words between us, like spikes, to keep myself from falling into him like a girl without bones. “You’re too old for me, Kolya,” I said. “What do I need a starik for?” But that was wrong, too, horrible. Oh God, how to be! I imagined myself a woman, but at times like this, I could not find my own outlines. For all my hours of mirror gazing, and the poems addressing my vast coterie of nonexistent lovers, I was a mystery to myself.

“Not so old anymore,” he said. “When the war’s over, six years’ difference will be—nothing.” He chucked me under the chin, as if I were ten.

“Kolya brought a letter from Volodya, children,” Mother said. Shame surged up where peevishness had been. How could I have forgotten to ask about my brother? What a self-centered wretch I could be. She produced an envelope and removed the contents, a sheet of long narrow stationery covered with my elder brother’s strong handwriting. We crowded around her as she read. “Dearest Mama and Papa, Marina, Seryozha, I hope this reaches you by Christmas, and that everyone’s well. I miss you profoundly. Feed my messenger and don’t let him drink too much. He has to come back sometime.”

Kolya lifted his glass of champagne.

“I have to admit, the war doesn’t go well. Heavy battles daily. I pray all this will come to an end soon.”

I could well imagine the cold, the wounded and the dead, the scream of the horses and the creak of wagons under the guns. This party now seemed a mockery, the whirling people dancing while my brother huddled in some miserable tent with his greatcoat wrapped about him.

“But Swallow”—his horse—“is doing well. He’s found a girlfriend, my adjutant’s mare. It’s funny to see how they look for each other in the morning.”

My mother wiped her eyes on her handkerchief, and gave a small laugh. “At least the horse is happy.”

“Brusilov”—the general of the Southwestern Army—“keeps our hopes alive. I admire him more than any man alive. The men are tough and true. With the help of God, we must prevail. Thinking of you all makes me feel better. Say hi to Avdokia for me. Tell her the socks are holding up. I kiss you all, Volodya.”

Mother sighed and folded the letter back into its envelope. “I don’t know how he can bear it. I really don’t.”

“His men would follow him off a cliff,” Kolya said. “You should be proud of him.”

She leaned on his shoulder. “You’ve always been such a comfort.” Then she spotted something—a quarrel brewing—that set her hostess antennae quivering, and she excused herself to attend to her guests.

Meanwhile, Kolya approached the table of books, picked one up and riffled through the pages, stuck his nose in and sniffed the verse. “Genius,” he announced. “I can smell it.”

“What does genius smell like?” Mina asked.

“Lilacs.” He sniffed. “And firecrackers.” He unbuttoned the chest button of his tunic and slipped the little book inside, pressed it over his heart, looking to see if I’d noticed. How could I not have? “I’ll read this on the train, and think of you.”

Yes, yes, think of me! But what did he mean, on the train? Was he leaving so soon? “Maybe you can just sleep on it, save you the trouble of reading.”

“That’s the best way to learn anything. It’s how I got through school.” He grinned. “So organic. Excuse us, ladies.” He took my arm. “I need to talk to our poet.” He led me away, leaving Mina yearning toward him like a sunflower, blinking without her glasses, and Varvara regarding him uneasily as if he were an unsteady horse I’d seen fit to ride. Where were we going?

He pulled me after him into the cloakroom and closed the door behind us. It was warm and close and full of the guests’ coats and furs smelling of snow. The transom let in only a filtered light. I could feel his breath in my ear as I stood pressed against someone’s sable, leaned back into the softness. Everything about me had gone both soft and prickly as if I had a rash. I felt like a fruit about to be bitten. I wanted to call out like a child, Kolya is going to kiss me! For once, no one was watching. No Father, no Mother, no governess or nanny, not even the maid or the cook.

I breathed in his strange scent. When I was a child, I actually stole one of his shirts and kept it on the floor of my closet behind my skates, to smell it when no one was looking, a smell like honey. How many years had I waited for this moment, imagining it? Since the day Volodya brought him home, a lively, chubby boy who became our Pied Piper. You could say it went back further, maybe I’d been a greedy, lustful little zygote. But the moment had been prepared like dry straw in a hayloft, waiting for a spark. And when our mouths met, I knew exactly why we had never kissed before. If his mouth, his tongue, were the only food left on the planet it would be enough. I would have let him do anything, right there in my parents’ house, standing among the furs. I had always considered Kolya out of reach, but impossibly, unbelievably, here he was in my arms, his face, his breath. His arms around my waist, my mother’s Après l’Ondée rising from my breasts, mingling with the honey of his body.

“Are you going to wait for me, Marina?”

“Don’t make me wait too long,” I whispered. “I’m not good at it.”

“I’ll hurry then.” He was unbuttoning his tunic. Were we going to make love right here among the coats? But he removed something from inside his uniform, a velvet pouch, which he pressed into my hand, still warm from his body.

“What else do you have in there?” I joked, hooking my finger to the open cloth, pretending to peep in. “Tolstoy?”

“Only Chekhov,” he said. “He’s smaller.”

The cloth of the little sack was soft when I rubbed it against my face, my swollen lips. “What is it?”

“Open it.”

I tried to work the cord, but my hands weren’t quite attached to my wrists. Inside, there was something hard—a large circle. I held it to the light. A bangle, white or some pale color, enameled, with arabesques of gold and black. “To remember me by.” He rubbed his lime-scented cheek against mine. “Don’t forget me, Marina.”

As if I ever could. Even dead I would remember him. I held up my forearm to admire the gift. How perfect it looked around my pale wrist. I could wear it without attracting too much attention—clever Kolya. A ring or a valuable jewel might have elicited parental scrutiny. Was this my arm? The arm of a woman who had received love gifts? I felt the way a goddess must feel when worshippers deposit sheep and bags of grain at her feet.

We fell into another kiss—his mouth, his honey, the length of him pressed to me, the furs around us—when the cloakroom door swung open, the light illuminating us. It couldn’t have been that bright, but it felt like a policeman’s searchlight. “What the devil?” I only had time to catch one glimpse of Dr. Voinovich’s surprised face—my father’s colleague at the university—as Kolya and I lunged past him, pretending we had not just been all but making love among the guests’ coats. I avoided my friends’ questioning faces. I didn’t want to share this, see myself in their eyes, I wanted this moment just for myself.

In the salon, the orchestra had launched into a tango. I had never danced the tango outside of dancing class, but I could have followed Kolya through a Tibetan minuet. We found a place amid the couples and away from the hall, where I expected Father to appear any second for a cross-examination. Kolya held my right hand in his left, the other decorously pressed to the small of my back—yet I knew the decorousness was only a ruse. I could feel him appraising the curve of my spine, the flare of my hips, knowing how his touch filled me with heat.

We began to move together. The tango was suddenly no longer a series of awkward turns and memorized motions from dancing class, one’s dress becoming damp from a partner’s nervous palms, but a love affair, proud and challenging, a drama. How perfect for us. He wasn’t a showy dancer, but easy and sure on his feet. Although I knew some of the dips and fast turns, I saw that they were unnecessary—that this, the silent conversation, the question and answer between man and woman, was the real dance. Although I had never danced with him before, I could feel his every intention, the tiniest signals. What must it be to make love with him—the firestorm of passion we’d engender. I prayed the orchestra would never stop, but too soon Mother descended to take Kolya away to meet some of her people, consigning me to my friends, who suddenly seemed so very young. My ship had already slipped its moorings, the sails rising to the wind.

FROM THE WINDOW OF my salmon-pink bedroom, I watched the snow whirl and worked on an aubade to that cloakroom kiss—the fur, his scent. What do you know about passion, you silly duck? I kissed the bracelet on my arm. How would it have been if we had shed our clothes in the cloakroom, and made love among the furs? I unspooled scenarios in my mind: Kolya and I in years to come, separated by some circumstance—tragic—then him catching sight of me across a room, like Tatiana with Onegin. How he would remember that moment in that long-ago cloakroom, how he would yearn. I wept just imagining it.

I thought of Kolya reading my poems on the train today, on the way back to his unit, seated among the other soldiers. Would he recognize himself in the figure of the ringmaster with his shiny moustache and his gleaming buttons? That poem was a love letter. I knew there was danger in showing too much of my passion—it frightened people, like it had the boys I’d kissed in stairways and at children’s parties. I shrugged the shawl from my shoulders—it was so hot in here—opened the fortochka window, and paced, stopping for the hundredth time to look at myself in the vanity mirror: my red hair, the round dark eyes of a Commedia Columbine, the freckles and blush in my cheeks. My fat lips, still impressed with his kisses. “Lyubimiy,” I whispered. Beloved. I could smell him in my hair. I wondered if he could smell me, too—I wished I had a scent of my own and not Mother’s, but it was a little late for that. I could only find peace by imagining myself a few years hence, looking back at all this as if it was already done. I sat back down at my desk and wrote:

You talk to the night.

I was her first, you say.

Someday it would be me who’d be quoted in girls’ diaries. Lovers would recite my verses in the depths of the night. I would be Makarova by then, the way people said Akhmatova or Tsvetaeva.

And you’ll say

You knew me once

When my dress was made of autumn leaves

And my hair a smoldering fire

As you smoke your cigar

Sip whisky with its peaty smoke.

Memory fades, but never that.

A kiss among furs,

Another kind of fire.

Akhmatova would do it with a gesture. And I put my left glove onto my right hand…Above my head, her profile hung in a frame between the windows. Seryozha had cut it for me from black paper. My muse, my lighthouse, with her Roman nose and bundle of long hair done up the way I wore my own. I imagined her at Wolf’s bookshop—maybe even today!—picking up my book of poems. Would she remember the girl she’d met one night at the Stray Dog Café? Under the glass of my desk, I kept the calling card she’d signed—the fine clear hand, the letters unconnected, the writing running uphill: To Marina—Bravery, in love as in art. A. I touched that A with my fingertips. Was I brave enough?

That Stray Dog world had already ended. I’d squeaked through the doors just as they were closing and managed to get down that famous staircase behind the Hotel Europa. How many afternoons I’d spent in the square, sitting on a bench under the statue of Pushkin, my sights on that subterranean entrance, hoping to catch a glimpse of her graceful figure, tall, stately, dark-haired, wearing a black shawl and her famous black beads. But I never saw anyone come in or out except men carrying crates on their shoulders. THE STRAY DOG ARTISTIC CABARET was a place of late night carousal, where the gods drank and smoked and recited, where they fell in love.

Mina and Varvara often kept me company in my vigil, attempting to appear blasé and sophisticated while eating nonpareils from paper cones. Varvara smoked her cigarette boldly in the open air, daring passersby to comment, meeting their disapproving eyes. Then came the autumn afternoon she’d had enough of my torment. She crushed her cigarette into the stone and said, “Why don’t we just go there sometime? This mooning around’s getting on my nerves.”

“They’d never let us in,” I said, but my heart already thumped with the possibility. Could we? They’d throw us out, but just for a moment, even an instant, to enter the holy of holies? It was like a door that I’d always believed to be firmly secured—and now she was questioning if it was even locked at all. “When would we go?”

“Tonight,” she said.

“We can’t,” Mina said, dropping a candy onto the pavement. “We have two tests tomorrow.”

But tests and grades were the furthest thing from my mind, which flew this way and that like a bird caught in a gallery, searching for an exit. Mother and Father were attending a party with the British second secretary and his wife…it would only be a matter of getting around Miss Haddon-Finch, our governess. Our nanny, Avdokia, wouldn’t tell. She enjoyed our small rebellions, sometimes even collaborated when she felt Father was being harsh. The Russian peasant is, at bottom, an anarchist.

First I had to set my trap. On the way home, I stopped at Wolf’s bookshop and bought Miss Haddon-Finch a special gift: Penrod, by Booth Tarkington, the latest arrival from England, having miraculously made it through the blockade. Not cheap, but it would be well worth it.

“Why, thank you, Marina, dear. What a thoughtful gesture,” she said that evening, stroking the cover of the book.

Ser

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...