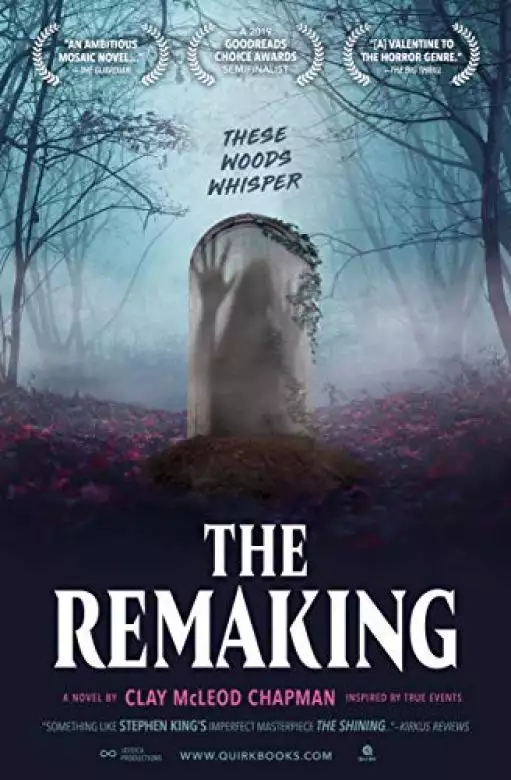

These woods whisper.

The pines at your back? You can practically feel the needles bristling in the wind. Lean in and listen closely and you’ll hear their stories. Everything that’s ever happened underneath that vast canopy of conifers. Every last romantic tryst. The suicides. The lynchings. You name it. These trees will testify to them. These woods have witnessed it all.

Whenever somebody from town wants to do something in secret, they come out here. Where they think they’re alone. Where nobody’s watching. They hide in the shadows, performing their little rituals beneath these branches, as if they believe these trees will keep their secrets for them. Their lovers’ liaisons, their midnight masses. They think nobody is listening in . . . but that’s simply not true. That’s not true at all. The trees are listening. Always listening. The woods know what the people of Pilot’s Creek have done. What we’ve all done.

I’ve lived in this godforsaken town my whole goddamn life. I know just about everything there is to know about the people here. Every last dark secret. Know how?

I listen. I listen to what the trees have to say. I listen to the woods.

So. What story do you want to hear? You want to know what drove Halley Tompkins to hang herself back in ’46? Or which men it was who strung Russell Parr up? Or how about that baby they found half-buried back in ’38?

No. You’re not here for any of those stories.

You want to hear about Jessica, don’t you?

Course you do. That’s why you’re here, isn’t it? Tonight of all nights . . .

Twenty years ago on this very evening. October 16, 1931.

We don’t have much time. Here it is, almost midnight, and I haven’t even begun telling you the tale of the Little Witch Girl of Pilot’s Creek.

Poor, poor Jessica.

You brought me a bottle? Don’t be stingy on me, now. That’s my price of admission. You want to hear a story, you better goddamn well have brought me an offering.

Alms for the minstrel. Something to wet my whistle so that I’ll sing. And Jessica’s story takes time. Takes the life right out of me.

Her story takes its toll on the teller, you hear? The price is too high . . . unless you got something for me to drink. My throat’s so parched, I don’t think I can tell it without a drop of that Lightning Bolt. I’ll sound like a bullfrog before I’m finished.

Did you? Did you bring me a little something? Just to take the edge off? Warm my insides? It gets so cold out here at night.

Thank you. Thank you kindly. That’s much better. Feel that fire working its way down my throat. Settling into my belly, like a bonfire.

Now. Where was I?

Let’s start with Jessica’s mother.

Ella Louise Ford was born right here in Pilot’s Creek. She’d come from good stock. Her family owned their fair share of acreage, growing tobacco. But there was always something off about that girl. Her mother sensed it from the get-go. None of that sugar and spice and everything nice for Ella Louise. No—that girl was touched. Little Ella Louise talked to the possums. She made charms out of dried tobacco leaves. She kept bees in mason jars and hid them underneath her bed. She couldn’t be bothered with frilly dresses or dolls like all the other girls. Not the porcelain kind, with pigtails and rose-painted cheeks. She made her own dolls. If you could even call them dolls. Looked more like totems. Like effigies. Twined together from twigs and wheat. Moss and leaves. Insects in their chests. Beetle hearts.

Try as they might, Mr. and Mrs. Ford could never break little Ella Louise of her strangeness streak. She never mingled with other children her age. None of them trusted her. All the other boys and girls sensed something was off about her and kept their distance. Mother Ford took it all too personally, as if their rejection of Ella Louise were an affront to the family name.

You got to understand, a town as small as Pilot’s Creek was crippled with superstitions. Rumors spread like cancer. Words hold power around here—and once word got around about Ella Louise’s peculiar habits, it wasn’t long before business for the Fords took a turn. It only got worse as Ella Louise grew up and became a young woman. Nobody wanted to be associated with her family. Be seen fraternizing with the Fords in the streets or paying them a visit at their home. Anyone who did suffered just as much of a cold shoulder as they did.

Understand now—all anyone ever had ’round here was their reputation. Simply to be seen in the midst of the Fords was enough to bankrupt businesses. Ruin entire legacies. You couldn’t wash the stink of that family off once it clung to your skin. That family was cursed.

Mother Ford took to punishing her only daughter. Bending Ella Louise over her knee and trying to spank that darkness right out of her. Taking a switch to her thigh, until the insides of her legs bled. Anything that might exorcise this witchery brewing within her.

There it was. That word, at long last. Witch. It was whispered among the other mothers. Their children. All through town. In church, even. It wasn’t long before all that gossip had grown into a downright din, the rumors spreading like wildfire, until everybody was talking about it. Until it was unavoidable.

Ella Louise Ford was a witch. Her debutante ball was an absolute disaster. Her mother moved heaven and earth to make it a night to remember. And in a way it was. It truly was . . . just not how Mrs. Ford had hoped for.

Ella Louise had always been a sight to behold. She looked as if she had stepped right out of an oil painting. Something you might see in a museum. Her skin was pale, always pale, with the slightest hint of pink illuminating her cheeks. A grin always played across her face, but you’d never say she was smiling. Her lips just curled heavenward all on their own. Her eyes, if they ever locked onto yours, were a deep green, as green as the deep sea, I reckon, to the depths of which no man has ever ventured. Or ever will.

What mysteries lie behind those murky eyes, only the Devil knows.

Coming out to polite society had always been a part of the way of life for Pilot Creek’s upper crust. Mrs. Ford had done it, her mother had done it, her mother before had done it, and on and on—so you damn well better believe Ella Louise was going to have her turn, no matter how much she protested. Mother Ford simply wouldn’t hear it. She refused to let the ritual go. For a girl to become a woman, she needed to be presented. To be unveiled. That was their God-given rite of passage.

Ella Louise was meant to wear a beautiful ballroom gown, made just for her. Pink silk. Mother Ford could barely hide her high hopes for her daughter when she handed over that dress. Even then, she held on to the fantasy that her own Ella Louise had a fighting chance of being welcomed into polite society . . . But at the very moment of her coming out, when every debutante is presented to the upper echelon of Pilot’s Creek, Ella Louise entered the dance room covered in mud from head to toe. Her gown was in tatters, all that pink torn to shreds. Dried leaves in her hair.

You could see her body moving beneath the ripped fabric, her pale flesh exposed to everyone. Practically the whole town, staring at her.

Nobody moved. Nobody breathed.

Ella Louise simply stood before them, smiling in that devilish way of hers, as if nothing were off about this at all. She asked her father for her first dance as a woman. Just as she had been instructed by her mother to do.

Mrs. Ford nearly fainted.

Ella Louise was cut off from that night forward. She was excommunicated from her own family. Disinherited. Her mother never uttered her daughter’s name again. Her own flesh and blood. It was as if Ella Louise had never existed. Never lived another day in their house.

So Ella Louise moved into the woods.

She made this forest her home. It’s unclear if she built her house herself or if someone had a hand in helping her, but a cabin manifested itself, seemingly out of nowhere. These woods are primarily composed of Eastern white pines that can reach up to a hundred feet, easily. They were originally used for building ship masts, centuries back, cut down and sent off to the naval yards in Norfolk. So much lush coverage, perfect for building a simple, one-story cottage with a fireplace cobbled together from stone and mortar. You could see the glow of a fire through its windows at night if you happened to be out here. But nothing and no one else actually lived out here. Not another soul.

Just Ella Louise. And Jessica.

If I were better at my own arithmetic, I might surmise that it was the night of Ella Louise’s coming out that served as the moment of her daughter’s conception. Whatever had happened to Ella out there in those woods to bring her back in such a muddied state, well, nine months later . . .

But then again, I’m no mathematician. And I sure as hell ain’t no baby doctor.

Nobody knows who Jessica’s father was. Or, more to the point, nobody owned up to it. Would you? Back then, in a town as small as this, you might as well have laid down with a leper. Ella Louise had become a burden for our town to bear. Pilot Creek’s very own pariah. Weeks, months, would go by and nobody would see her rummaging about town. Hear her voice begging for pocket change. Even think about her out here, living alone, for all those years.

But then the sound of a baby crying lifted out from the woods. Jessica’s wailing filled this forest. It echoed all the way into town. Into the ears and dreams of every last townsperson.

Ella Louise had a daughter now.

Other theories of paternity abounded. Such as Jessica had no father. She was immaculately conceived by the Devil himself. Ella Louise had made her pact with the Lord of Flies and he begot him an only daughter. Her very existence was a morbid reminder of her mother’s unholy union with Beelzebub. Ella Louise and Jessica would come into town for their groceries, just like everybody else. Can’t live off root vegetables alone, now. But when folks laid eyes on that little girl in Ella Louise’s arms, all they ever saw was the princess of darkness.

We’d only see Jessica whenever she’d come into town. Watched her grow in these fits and spurts. Months would go by and there she’d be, traipsing down the road with her mama. Always holding her hand. Always keeping her eyes down low, on the ground. She didn’t attend school with the rest of us. Didn’t learn about life like the rest of us. Whatever lessons she got came from her mother back at their cabin. I can only imagine what she was taught out there in those woods. The Devil’s arithmetic.

When Jessica turned nine, she started coming into town on her own. Always had a list of goods to fetch from the store for her mother. She didn’t have Ella Louise at her side, holding her hand and braving the lane anymore, so some of us boys felt a bit more emboldened to share our inherited distaste for Jessica. Children took to throwing stones at the girl. Calling her all kinds of names. I’m not proud to admit that I myself fetched a pebble or two in my boyhood, tossing it at little Jessica’s back.

Once, I struck her right in the shoulder. My aim was true.

She turned right to me. Even though I was among a dozen other kids, all of them holding their own rock, she knew I’d been the one to throw it. Knew the rock had come from my very hand. She pinched her eyes—and without ever saying a single word to me, I heard Jessica’s voice in my head, as if my own thoughts were boiling over in my skull. She whispered to me.

Cursed me. What’d she say? I’ll never tell. Not unless you’ve got another bottle on you.

Suffice to say, her curse worked. I can’t stop thinking about her. Not back then, not even now. She left an imprint of herself, a shadow, on my mind.

Little Jessica has never left. Nobody ever mentions how beautiful she was. Her mother may have been a picture of perfection, such a lovely face, but Jessica . . .

Jessica took my breath away. She was an angel. But for the life of me, I can’t remember what the color of her eyes was. I can’t remember the color of her hair. Or the features of her face. I can’t remember any of her.

I can’t describe her. Words escape me. She returns to me, night after night, for over twenty years now—and yet, the moment I wake, the vision of her dissipates. Gone. Just like that. I can only see her in my dreams.

As a boy, I was frightened of her. What she might do to me. But I couldn’t stop myself from welcoming her into my head. Into my sleep. Now I wait for her. Yearning for her to return.

Why won’t she let me go?

If Ella Louise had been touched with magic, then her daughter was downright blessed. Jessica had twice the talent her mother had.

Talent. What the hell else would you call it?

Ella Louise nurtured her daughter’s talents. Taught her all she knew. If Mother Ford had done her damnedest to stamp out the fire brewing within her child, then Ella Louise went ahead and fanned those flames within Jessica. Out here, in these woods, nobody was going to stop them.

It was said that Jessica could commune with wildlife. She could mend a bird’s broken wing with just the touch of her hands. Weeds would wilt from under her touch. Just a simple tap from her finger against the soil and out sprouted a toadstool. A dozen mushrooms.

This was what people believed, at least. What folks whispered among themselves in town. Nobody ever saw these things with their own eyes. Not that we needed to.

We believed.

Any boys brave enough—or dumb enough—to set foot into the forest and sneak a peek through the windows of their cottage would get pinkeye for their troubles. Anyone who came close to their home would break out in a rash, their skin scorched with poison ivy. Anyone who spoke ill of Ella Louise or Jessica within their earshot would suddenly discover an eruption of blisters covering their tongue.

None of this was simply a coincidence. None of this was chance. We all knew what Jessica was. What her mother was. What those two were up to out here in the woods.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved