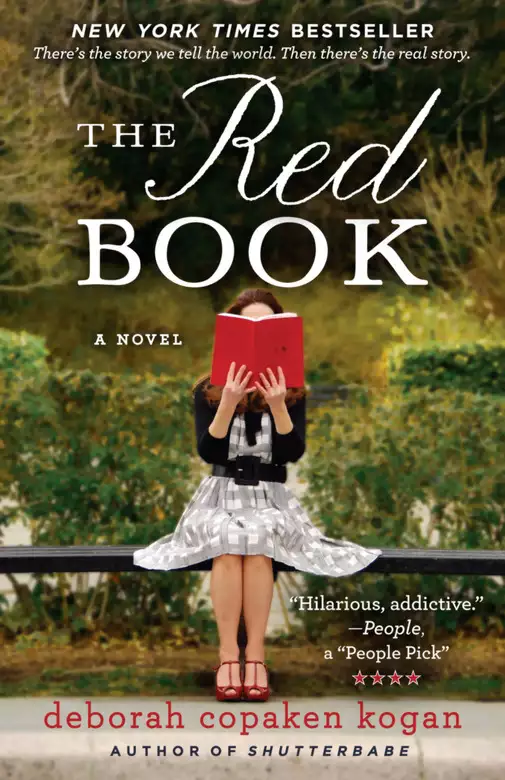

The Red Book

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The Big Chill meets The Group in Deborah Copaken Kogan’s wry, lively, and irresistible new novel about a once-close circle of friends at their twentieth college reunion.

Clover, Addison, Mia, and Jane were roommates at Harvard until their graduation in 1989. Clover, homeschooled on a commune by mixed-race parents, felt woefully out of place. Addison yearned to shed the burden of her Mayflower heritage. Mia mined the depths of her suburban ennui to enact brilliant performances on the Harvard stage. Jane, an adopted Vietnamese war orphan, made sense of her fractured world through words.

Twenty years later, their lives are in free fall. Clover, once a securities broker with Lehman, is out of a job and struggling to reproduce before her fertility window slams shut. Addison’s marriage to a writer’s-blocked novelist is as stale as her so-called career as a painter. Hollywood shut its gold-plated gates to Mia, who now stays home with her four children, renovating and acquiring faster than her director husband can pay the bills. Jane, the Paris bureau chief for a newspaper whose foreign bureaus are now shuttered, is caught in a vortex of loss.

Like all Harvard grads, they’ve kept abreast of one another via the red book, a class report published every five years, containing brief autobiographical essays by fellow alumni. But there’s the story we tell the world, and then there’s the real story, as these former classmates will learn during their twentieth reunion weekend, when they arrive with their families, their histories, their dashed dreams, and their secret yearnings to a relationship-changing, score-settling, unforgettable weekend.

Release date: May 7, 2013

Publisher: Hachette Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Red Book

Deborah Copaken Kogan

Okay, so here I am, just like back in college, writing this thing with only forty minutes left to go before the deadline. Plus ça change. (She pauses briefly, for inspiration, to hunt down the Fifteenth Anniversary Report, which is wedged between all the other red books and her freshman facebook—the very facebook, she’s been trying to explain to her offspring, which was the original model for their beloved virtual one, but they look at her as if she’s crazy, something she’s not so sure they’re incorrect to assume these days, except of course in this instance.)

So. Where were we? Right. My life these past five years. And can I just say that when I accepted Harvard’s invitation to join the class of ’89, I don’t remember agreeing that every five years, for the rest of my life, I’d be forced to complete another writing assignment. There’s a reason I nearly failed freshman expos, people!

Just saying.

Ack! I got sucked into rereading the Fifteenth Report. You guys are fascinating. A tribute to your alma mater. I can’t even understand half of the things you’re doing, but I’m glad you’re out there doing it. Someone has to figure out the secrets of the universe, and better you than me, and I guess this is where I should probably take a moment to formally apologize to the TA I called (Joe? John? Josh?) in a panic at 3 A.M. before the Science A final, but the funny thing is, it’s been over two decades since that call, and I still don’t understand dark matter or quarks, though you did a valiant job trying to explain them. Okay, twenty minutes left. Come on, Addison, you can do this.

Okay, so, I guess the biggest change since my last entry is that I’ve finally entered the modern age: I have an actual Web site of my work (http://www.addisonhunt.com), I’ve hung out a shingle on etsy.com (http://www.etsy.com/shop/AddisonHunt?ref=seller_info), and I’ve been taking classes in QuarkXPress—finally! A quark I understand!—and PhotoShop to stay on top of the latest digital technologies. Still painting as always, but my process has evolved from a kind of neo abstract feminist expressionism into a photo realistic rendering of the mundane. That’s artist-speak for “I used to throw paint on a canvas and use the palms of my hand to smear it here and there as a visual representation of unconscious female desires. Now I make intricate drawings of my hairbrush.”

Wish I could drone on longer, but there are Christmas cards to send out, and I have to help Houghton build the Parthenon for social studies by tomorrow, and Thatcher needs to be picked up from guitar, and Trilby’s boarding school applications are due in two days. As you might expect, I’m a little behind.

CLOVER PACE LOVE. Home Address: 102 East 91st Street, New York, NY 10128 (212-546-7394). Occupation and Office Address: Managing Director, Lehman Brothers, 1897 Broadway, 41st floor, New York, NY 10014. Additional Home Address: 4 Lily Pond Lane, East Hampton, NY. E-mail: [email protected]. Graduate Degrees: M.B.A., Harvard ’98. Spouse/Partner: Daniel McDougal (B.A., Boston College ’95; J.D., Yale ’98). Spouse/Partner Occupation: Attorney, Legal Aid Society.

I wish I had something more interesting to report other than that, aside from a brief detour at the B-school midcareer, I’ve been with the same company, Lehman Brothers, since the week after graduation. I sometimes wonder what it would have been like to have jumped around a bit more, but one of the reasons I’ve stayed with Lehman for so long is that I actually love both my workplace and my job. I find the challenges of managing both people and equity fascinating, and though I’m proud to be one of only a handful of female leaders in our company, it’s still shocking to me that we’re not better represented in positions of power on Wall Street.

I was named managing director of my group in July 2004. I lead a large and vibrant team focusing on mortgage-backed securities, our most profitable department in fiscal year ’07.

On the love-life side of the equation, I finally found my soul mate, Danny McDougal, after I allowed my former roommates to create a profile for me on Match.com. They called it an “intervention,” which they staged during the annual July Fourth weekend we spent together at my house. Addison took the photo, Jane wrote the text, and Mia tried to use her Meisner techniques to coax me out of what she called my “robotically corporate” communication skills. (Apparently asking a man on the third date whether he’s willing to change an equal number of diapers as his wife is a Dating Don’t; luckily Danny found both my honesty and the two-page, single-spaced document mapping out a future of equitably shared domestic responsibilities I presented to him on our ninth date slightly weird but charming enough to stay the course.)

Danny and I closed the deal, so to speak, six months later and found our dream house, an 1897 brownstone in Carnegie Hill, which we gutted and renovated over the course of the next year. If I’d better understood the various stresses of renovating a property while simultaneously living in it, I might not have insisted we do it during our first year of marriage, but when you get hitched at the ripe old age of thirty-nine, there’s no time, as they say, like the present.

Meanwhile no children yet, but they are definitely high up on our list of goals for FY09, and we hope, with any luck, to bring a couple of them to our twenty-fifth!

MIA MANDELBAUM ZANE. Home Address: 45 San Remo Lane, Los Angeles, CA 90049 (310-589-0923). Additional Home Address: 17 rue des Ecoles, Antibes, France. E-mail: [email protected]. Spouse/Partner: Jonathan Zane (B.A., University of Maryland ’70; M.F.A., UCLA ’74). Spouse/Partner Occupation: Film director. Children: Max Benjamin, 1992; Eli Samuel, 1994; Joshua Aaron, 1998; Zoe Claire, 2008.

As I sit here typing this, the newest member of the Zane Train—our tiny caboose, Zoe—has finally fallen asleep in her BabyBjörn, the only place she seems to want to engage in this kind of activity. Those of you familiar with the medieval torture device that is the Björn will understand what this means: I’ve had a baby glued to my middle-aged torso, without reprieve, every day since her birth. In fact, I think I must have been single-handedly responsible for the recent spike in Johnson & Johnson stock, as I’ve decimated the entire West Coast supply of Motrin to deal with the inevitable backache. Good practice, I suppose, for all the aches and pains we’ll all be feeling soon enough. (Have twenty years actually gone by so fast? I walk around assuming I’m still twenty-two, then I catch a glimpse of myself in a store window or a bathroom mirror and am suddenly and brutally shocked back into reality. Who’s that scary chick with the streaks of gray in her hair and the deep lines around her mouth? Oh, right. That’s me.)

It’s been, well, interesting, to say the least, to run around the country visiting colleges with my eldest while breast-feeding an infant. I’ve been so physically and mentally addled, in fact, that the other day Eli, my second, walked into the kitchen in search of a snack—oh my God, those boys can eat!—and I said, “Since when did you grow facial hair?” and he said, “Um, like a year ago, Mom? Duh.”

Okay, so here’s the part where I’m supposed to tell you about the total awesomeness of my career, followed by a rattling off of my awards and accolades, but the only award I have sitting framed on my mantel is a “#1 Mom” plaque my eldest, Max, made out of macaroni and clay for Mother’s Day circa 1996. Max was born soon after I got married, which was soon after I graduated, which was probably too soon, but there you have it. Max was followed closely by Eli, who was followed four years later by Josh, and though I was still going out on auditions from time to time, suddenly I had three young boys and little time, energy, or desire to keep banging my head against that wall. Plus, the kind of work I was able to land as an actress—a Tums commercial here, a public service announcement there—never felt as fulfilling or stimulating as spending an afternoon on the floor with my children. I know that sounds like an excuse, and on some level I’m sure it is, but it’s also as true a statement as any: What I’d planned as a short maternity leave turned into seventeen years. And while they might not have been the most mentally challenging or professionally rewarding years of my life, spiritually they were rich and full. So rich and so full that when my husband asked me what I wanted for my fortieth birthday, I joked, “Another baby.” But then the more I thought about it, the less it felt like a joke. Hence, Zoe Claire, now stirring in her baby carrier, rooting around for some lunch.

That’s not to say I spend every hour taking care of my kids, because until Zoe was born, there were many years when they were in school most of the day. I know I’m lucky to have been given the gift of time with them, so I try to pay it forward, in some way, every day. This past year and a half we’ve been particularly busy hosting fund-raising events at our home to help raise money for the Obama campaign. (G’Obama!) I’m also active in our local chapter of Planned Parenthood and in the soup kitchen committee at our synagogue, B’nai Israel. I’ve been running the Pinehurst School’s annual fund-raising auction ever since our son Max was in kindergarten, and I do outreach in Watts to help locate scholarship students who might not otherwise have heard of the school. Pinehurst has been a great learning environment for our three sons: small classes, one-on-one attention, a focus on the whole child. Zoe seems eager to get started as a student there as well—she often wails when her brothers leave in the morning—but for now, I’m hanging on to her lovely babyhood. Or, rather, her lovely babyhood seems to be hanging on to me. Constantly.

Jonathan, my husband, continues to direct romantic comedies. His latest, Give and Take, featuring Hugh Grant and Keira Knightley as former schoolmates caught on different sides of the law, should be hitting the theaters just before we head back for reunion, so definitely go see it if you get a chance!

Life, as they say, has been good to us, and my husband and I feel blessed and fortunate to be where we are. We have our health, four beautiful children, good friends, and a sturdy roof over our heads. A few years ago, we renovated an old stone house in the south of France, where we try to retreat every August, depending on Jonathan’s shooting schedule, so if you’re ever near Antibes during the summer, drop by! We’ll open up a bottle of local wine and watch the sun set over the Mediterranean. That’s a real invitation, so take me up on it. If you’re lucky, you’ll get to spend time with Jane as well, who always makes it down for at least a week with her daughter and her beau, Bruno. And if Jane ever makes an honest man of Bruno, we’ve promised to hold the wedding for them there as well. (Jane? Oh, Janie-pie? Hint hint.)

I look forward to catching up with everyone at reunion.

JANE NGUYEN STREETER. Home Address: 11 bis, rue Vieille du Temple, 75004 Paris, France (33 1 42 53 97 58). Occupation and Office Address: Reporter, the Boston Globe, 11 bis, rue Vieille du Temple, 75004 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected]. Spouse/Partner: Bruno Saint-Pierre. Spouse/Partner Occupation: Editor, Libération. Children: Sophie Isabelle Duclos, 2002.

I am a card-carrying rationalist. I do not believe in God or higher powers or anyone up there manipulating our puppet strings, but every once in a while I do wonder why some of us are targeted, seemingly more than others, to endure loss. I’m not complaining. In fact I’m grateful for my life every day. It’s just that when I sit down to read these entries every five years—actually, more like devour them in a single, all-night, sleepless gulp—what strikes me most profoundly about the nature of our disparate paths is not the infrequent “I lost my spouse” or “My father died last year,” but rather the fortuitous lack of life-altering tragedies in the majority of these entries.

I consider myself relatively happy, emotionally stable, and extremely lucky compared to many of the people I’ve met over my nearly two decades as a reporter, but examined closely, as this book forces those of us masochistic enough to send in these updates to do, my life reads more like a bad soap opera than like the life of a typical Ivy League grad, whatever typical means in this context.

As some of you know, I lost both of my parents and all three siblings to war before the age of seven. After making my way to Saigon, I was adopted by Harold Streeter, the army doctor who treated me upon my arrival in the city, and his wife, Claire. Then, a year after my new parents brought me home to their house in Belmont, Harold died of a freak staph infection he contracted at the hospital where he worked.

Then, thank goodness, there was a long lull, about which I’ve already written extensively in these pages, so I’ll just summarize here to refresh our collective memory: After college, I moved to Paris, to work for the International Herald Tribune and to live out my Jean Seberg expat fantasies; this led to a freelance gig with the Christian Science Monitor, which got me out into the world beyond, where I began to specialize in covering global refugee crises. I met my husband Hervé on the back of a truck in Rwanda. I was asked to take over as the Paris bureau chief for the Globe a few years after that, until they shut down the bureau. They kept me on as a staff reporter, however, which basically means I work out of my home office when I’m in town, which suits both the Globe and me just fine, at least for now. I gave birth to our beautiful daughter Sophie, whom many of you met at the last reunion, in the summer of ’02. Because of Hervé’s humane French benefits, I never had to worry—as I often read in these pages that many of you do—about going bankrupt paying for Sophie’s medical bills, schooling, or child care. (Although now that Obama just won the presidency, yesterday as I write this, I’m assuming the U.S. will finally get its act together on the health care front.)

I took predictable joy in these tragedy-free years, but as they began to accumulate, year by year, I started to get cocky, believing that the “curse” of bad luck that had plagued my earlier life was finally, thrillingly over.

Then, in late 2004, my husband’s car was hijacked near Jalalabad, Afghanistan, where he was on assignment for the French newspaper Libération. Or at least that’s what we think probably happened, as his body wasn’t found until six days later, tossed into a ditch. For the next six months, our daughter, who was only two at the time, kept looking for him in all the places she remembered her father taking her: a restaurant in our neighborhood, the patisserie on the corner, the playground in the Place des Vosges. And then she stopped looking or even talking about him altogether. A year later, I fell in love and moved in with my current partner, the wonderful Bruno Saint-Pierre, who was Hervé’s editor at Libé and the shoulder I often leaned on after Hervé’s death.

Then, a few months ago, Claire, my adoptive mother, the most solid rock of my life, called to tell me she’d been diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer. Her prognosis is not good. The doctors won’t give her an exact time frame, but they said she’s probably looking at six months tops. She still lives in her (our) old house in Belmont, so I’ll definitely be back and forth between Paris and Boston this fall and winter, but I’m also hoping she sticks around long enough to see the buds on her rosebush in May and the smile on her grandchild’s face in June when Sophie and I arrive for reunion.

Chapter 1Addison

It had simply never occurred to Addison that the Cambridge Police Department not only kept two-decade-old records of unpaid parking tickets, but that they could also use the existence of her overdue fines, on the eve of her twentieth college reunion, to arrest her in front of Gunner and the kids. If such a scenario had struck her as even remotely possible, she’d be thinking twice about zooming through that red light on Memorial Drive.

But it hadn’t, so here we go.

“Oh my God, look at these idiots,” she says, slamming her hand down hard on the horn of her blue and white 1963 VW Microbus, which she purchased online one night in a fit of kitsch nostalgia. Or that’s the story she tells friends when they ask what she was thinking buying a vehicle that takes weeks or even months to fix when it breaks down, for want of parts. “Take my advice: don’t ever go on eBay stoned,” she’ll say, whenever the conversation veers toward car ownership, online shopping, or adult pot use. “You’ll end up with a first generation off the master Cornell ’77 along with the friggin’ bus the dude drove to the show.”

While the story is technically true, the impetus behind the purchase was much more about economic necessity, practicality, and appearances than Addison likes to admit. For one, she and Gunner couldn’t afford a new Prius. They refused, on ecological principle, to buy a used SUV, or rather they refused to be put in the position of being judged for owning an SUV. (While they loved the earth as much as the next family, they weren’t above, strictly speaking, adding a supersize vehicle to its surface for the sake of convenience.) A cheap compact, with three kids and a rescued black Lab, was out of the question. And they couldn’t wrap their heads around the image of themselves at the helm of a minivan. To be a part of their close-knit circle of friends, all of whom have at least one toe dipped in the alternative art scene in Williamsburg, meant upholding a certain level of épater-le-bourgeois aesthetics. If a minivan or even a station wagon could have been done ironically, believe her, it would have.

Traffic in front of the Microbus has halted, an admixture of the normal clogged arteries at the Charles River crossings during rush hour compounded by the arterial plaque of reunion weekend attendees, those thousands of additional vehicles that appear every June like clockwork, loaded up with alumni families and faded memories, the latter triggered out of dormancy by the sight of the crimson cupola of Dunster House or the golden dome of Adams House or the Eliot House clock tower, such that any one of the drivers blocking Addison’s path to Harvard Square might be thinking, as Addison is right now (catching a glimpse of the nondescript window on the sixth floor of that disaster of a modernist building that is Mather House), There, right there: That’s where I first fucked her.

No, that wasn’t a typo. Prior to marrying Gunner, Addison spent almost two years in a relationship with a woman. This, she likes to remind everyone, was before “Girls Gone Wild,” before the acronym LUG (“lesbian until graduation”) had even debuted in the Times, so she’d appreciate it if you wouldn’t accuse her of following a trend, okay?

If anything, Addison has come to realize, thanks to a cut-rate Jungian who came highly recommended, Bennie was just one more way—like the roommates she wound up choosing—she’d been trying to shake off her pedigree, to prove to herself and to others that she had more depth and facets than her staid history and prep school diploma would suggest. Addison may have been one of the eighth generation of Hunts to matriculate from Harvard, but she would be the first not to heed the siren call of Wall Street. For one, she had no facility with numbers. For another, she’d seen what Wall Street had done to her father. He, too, had been enamored of the stroke of fresh Golden’s on canvas from the moment he could hold a paintbrush, but he’d tossed his wooden box of acrylics into the back of the closet of his Park Avenue duplex—where it gathered dust until Addison happened upon it one day during a game of hide-and-seek—because that’s what Hunts did: They subsumed themselves into their Brooks Brothers suits. The cirrhosis that killed him in his early fifties, when Addison was just a sophomore in college, was no act of God. It was an act, every glass-tinkling night, of desperation.

Bennie was the first person in her life to make that suggestion. Out loud, at least, and to Addison’s face. And though both Bennie and her pronoun were aberrations in the arc of Addison’s sexual history, what the two had together—although Addison would only be able to understand this in retrospect, per the cut-rate Jungian—was love.

“Is Bennie coming this weekend?” Gunner asks. He’s been hearing about this mythical creature, Bennie Watanabe, ever since he and Addison bumped into each other that summer at a seaside taverna in Eressos, where Addison had gone with some vague and mostly unrealized notion of studying the poems of Sappho in their place and language of origin as inspiration for a series of abstract studies of the Isle of Lesvos she never ended up finishing, and Gunner had retreated to start what would become, ten years later, his first and thus far only published novel, a coming-of-age tale that would feature, after his run-in with Addison, a girlfriend/muse from a socially prominent family who dabbles in bisexuality with a Japanese American lesbian before marrying her old boyfriend from prep school following their chance encounter at a taverna in the Lesvos city of Molyvos (because something had to be fictionalized, and it had a picturesque port he could describe, knowing boats as he did, in intimate, Moby Dick-like detail).

The Walls of St. Paul’s had been sufficiently well received—especially the boat parts, which the New York Times critic, an aquatic enthusiast himself, dubbed “Melvillean”—that Gunner was paralyzed by a decade-long writer’s block. Though publicly he’s always insisted that Tilly, his protagonist’s self-delusional, bisexual wife, is nothing like Addison, privately Addison knows that the vaguely unflattering, unhinged portrayal of their early years together is a roman à clef in every sense of the phrase except for the inventively imagined scenes of three-way sex among the protagonist, his wife, and the random assortment of foreign women they picked up along the way during their first year of marriage, which was spent, as Addison and Gunner’s had been, backpacking around the globe. For as much as Gunner had begged his new bride to bring another woman into their bed, Addison did not share this same fantasy, and, in fact, she resented her husband’s preconceptions that such a scenario was possible. Bennie was an anomaly, she kept telling him. A momentary slip of the self.

“So what exactly is your regular self when it comes to sex?” Gunner recently asked, after Addison once again claimed exhaustion as an excuse against her husband’s amorous onslaught.

“I’m just tired, okay? I deal with three kids and their endless pits of need all afternoon while you’re off in Dumbo in your ‘garret’ writing the great American novel, and my paints go untouched. I’m sorry. I’m just not in the mood.”

“You’re never in the mood,” said Gunner, sulking. “We need to talk about this, Ad. It’s affecting my work.”

Don’t you fucking blame me, she thought. And while we’re on the topic, what about my work? But wanting to avoid conflict at such a late hour, she said only, “Yes, sure, okay,” and kissed his forehead. “Let’s talk about this when I’m more rested. I’m sorry, I really am. When you finish your novel and sell it, maybe we can use some of the money to go away, just the two of us.”

“That’d be great,” his voice said, though the rest of him seemed less convinced.

And another night of lovemaking was once again averted.

It’s been a year—no, fourteen months—Addison figures, since they’ve had sex. All right, maybe fifteen or sixteen. She’s kind of lost track. She understands this must be frustrating for her husband, but she can’t will herself to feel passion where none lingers. She tells herself it’s all because of him—his lack of a successful follow-up, his moping around feeling sorry for himself, his sullen moodiness, his financial impotence. But at night, when she finds quiet moments alone for release, it’s images of ripe breasts and swollen vulvas that send her over the edge.

“Oh, please, I’m as heterosexual as they come, and I have an entire encyclopedia of breasts and va-jay-jays in my head,” her friend Liesl recently told her when Addison wondered aloud, over a Red Stripe, whether her pregame masturbatory fantasies were within the realm of heterosexually normal. “There’s no such thing as ‘normal’ when it comes to sex. You of all people should know that.”

“But do you fantasize about other stuff, too?” Addison wondered. “You know, besides the lady parts.”

“You mean like the scene where I’m lying on the pool table at a frat house? Or where I’m Kate Winslet on the Titanic, being sketched by Leonardo DiCaprio?”

“See? I don’t have any stuff like that,” Addison lamented.

“Oh, please,” Liesl said, laughing. “You’re welcome to borrow mine.”

But later that night, when she tried to conjure the pool table scene, the undergrad boys turned into undergrad girls. And on the Titanic she herself was being sketched by Kate Winslet.

“I have no idea if Bennie’s coming,” she now tells Gunner, “although she did just send me a friend request on Facebook.”

“Really? What’d she say?”

“Nothing.”

No matter how many times her kids have made fun of her for feeling insulted by friend requests made without even an intimation of a greeting—a “Hello there!” or “Long time no see!”—Addison is pretty sure she’ll never get used to the idea that modern online social interaction completely eschews the laws of common courtesy, never mind dilutes, forever, the meaning of the word friend. Her fourteen-year-old daughter has 789 “friends.” 789 friends! What can that even mean when Addison, with forty-two years of nonvirtual social interaction under her belt, has 139 “friends,” all of whom sought her out like cancer cells in search of a new blood supply from the minute she created a login and a password, half of whom she only vaguely remembers, if at all, from this or that era of her life?

Sure, anyone who showed up in college with a typewriter, as she did, then wound up purchasing one of those pathetically quick-to-crash first Macs, was just finding her sea legs in the world of online social networking, at first to monitor her still-technically-too-young-to-join-Facebook children’s profiles, then because, once ensconced and entrapped, it felt mildly comforting to reconnect with those who’d disappeared from one’s Filofax-era life. Even if reconnecting meant simply scrolling down an endless stream of mundanities—Joe Blow has the flu; Jane Doe is contemplating eating the last Girl Scout cookie—and wracking one’s brain to come up with a comeback that was both restrainedly witty and seemingly effortlessly so. “Blow, Joe, Blow!” “Courage, Jane.”

When Bennie’s message-free friend request suddenly appeared on Addison’s screen, attached to a profile photo containing Bennie, her children, and her partner, Katrina Zucherbrot—aka Zeus, the German-born artist whose ten-foot-tall sculpture of a phallic vagina had recently been added to the permanent collection at the Whitney—Addison felt slight tinges of nostalgia (for time past), jealousy (over Zeus’s success), and curiosity (to check out Bennie’s photos), but she was otherwise unmoved. On the other hand she’d read, with breath-accelerating, body-chemical-changing fascination, all about Bennie and Zeus and their Petri-dish progeny five years earlier, in the Fifteenth Anniversary Report, wherein Bennie had described, in raw detail, how each partner had given birth to one child using sperm from the other’s brother. And she’d been riveted by the recent Twentieth Anniversary red book, in which Bennie announced her intentions to retire from Google at the end of 2009 to begin the next phase of her life, in which she planned to start a foundation that would give scholarships to bullied gay teens and fight for the right of gay marriage.

Clicking through Bennie’s photo albums on Facebook had been voyeuristically interesting, to be sure, but the act lacked both the context and enlightenment that Bennie’s narratives were able to offer. Addison was struck only by the universality of the visual banality therein: Here’s the happy family on vacation at the beach; and here they are opening presents on Christmas; and oh, look, here they all are standing in front of the Brandenburg Gate with Zeus’s parents.

“That’s bullshit!” Bennie had hurled at her, that frigid January of their senior year, just after finals, when Addison abruptly broke off the relationship. “You’ve never heard of a turkey baster?”

Addison had come to Bennie’s spartan room in Mather House, dry eyed and rational, to explain that as much as she’d enjoyed the nearly two years they’d spent together as a couple, as much as she’d learned about herself and about her body’s ability both to give and receive pleasure—skills she would, she assured Bennie, touching her lover’s forearm, treasure forever—she’d decided that she simply couldn’t wrap her head around the concept of spending the rest of her life with a woman. “I mean, experimenting in college is one thing, but I want to have kids one day,” she said. “A normal family.”

Hence Bennie’s initial comment about the turkey baster, followed by more colorful castigations after Addison admitted to having joined the mile-high club with her male seatmate on the Delta shuttle home from break. “You bitch!” Bennie wailed. “You fucking two-faced, dick-sucking bitch! And if you touch my arm one more time in that patronizing way I will deck you.” Which was soon followed by: “And what the hell do you mean by ‘experimenting,’ you entitled piece of shit? What happened to ‘I’m in this for real, Bennie, I promise. You’re my soul mate. My snuggle bunny. I want to make love to you forever’? Jesus fucking Christ, Ad, I’m not some tab of acid you ate in prep school to gain ‘experience’ or cool points. I’m not your Dead show phase or a stranger you fuck in an airplane restroom because it’s on your list of things to do. I’m a person! I have feelings! And up until five minutes ago, I was stupid enough to have given you the benefit of the doubt that you were an actual human being with feelings, too.”

“Nothing?” says Gunner.

“Not a word,” says Addison.

“So did you accept or ignore?”

“I haven’t decided yet. I mean, do I really want to read, ‘Bennie Watanabe is drinking coffee’ or ‘Bennie Watanabe is taking her daughter to school’ or ‘Bennie Watanabe just cashed in the remainder of her Google stock, and now she has more money than you, Warren Buffett, and God combined, so suck it’?” She honks the horn anew, motioning wildly and fruitlessly to the driver in front of her. “Jesus, go through! Go through! We’re going to be late for the—”

“The luau?” Gunner laughs. He’d agreed to come this weekend, but only after Addison had pointed out that she’d attended his twentieth reunion the prior year without whimper or complaint. In fact, she’d continued, unable to stop herself, she’d even gone onto the Yale Web site herself, using Gunner’s login, and made all the reservations and purchased the tickets for him. “I do everything for this family,” she’d mumbled under her breath, “so just do this one fucking thing for me,” but either Gunner didn’t hear this last part, or he decided not to take the bait.

Gunner’s stance on all things domestic has remained somewhat militant since Addison broached the idea of having children with him when they were still, according to Gunner, too young to spawn. He wanted the chance to write unencumbered for a decade or so, until they were into their mid-thirties; to have the freedom to sleep late and work whenever the muse struck. Addison tried explaining to him that since her art was gynocentric, she needed to experience childbirth and motherhood in order to be fully conversant in her field. More saliently (she showed him a chart of female fertility, with its gradual downward slope between eighteen and thirty-five, after which the line made a sudden nosedive toward zero), if they were going to have children, she ideally had to fit it in before she turned thirty-five.

“Fine,” Gunner said. “You want kids now, you deal with their mess.” He was the eldest of five. He knew from whence he spoke. Addison was an only child who’d never lacked for the kind of pocket change that drives adolescent girls to babysit.

So while Gunner sat frozen in front of his computer, searching for his muse, Addison produced a series of squalling Griswolds in rapid succession, taking on the full responsibility, as preordained, for their care. She fed them, first from herself, then from a jar, then off a plate. She changed their diapers and taught the. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...