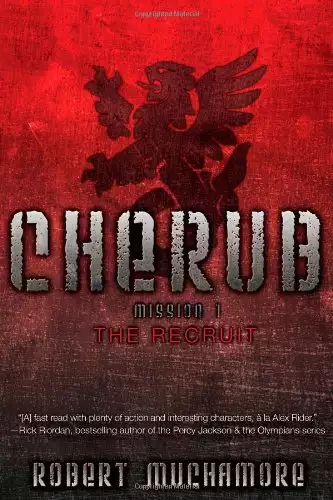

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A terrorist doesn't let strangers in her flat because they might be undercover police or intelligence agents, but her children bring their mates home and they run all over the place.

The terrorist doesn't know that a kid has bugged every room in her house, cloned the hard drive on her PC, and copied all the numbers in her phone book. The kid works for CHERUB.

CHERUB agents are aged between ten and seventeen. They live in the real world, slipping under adult radar and getting information that sends criminals and terrorists to jail.

CHERUB: THE RECRUIT is read by Simon Scardifield.

Release date: December 21, 2010

Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Recruit

Robert Muchamore

CHAPTER 9

STRANGE

This room was flashier than the one at Nebraska House. It was a single for starters. TV, kettle, telephone, and miniature fridge. It was like the hotel when his mum took him and Lauren to Disney World. James didn’t have a clue where he was or how he’d got there. The last thing he remembered was Jennifer Mitchum asking him up to her office after he got back to Nebraska House.

James burrowed around under the duvet and realized he was naked. That was freaky. He sat up and looked out of the window. The room was high up overlooking an athletics track. There were kids in running spikes doing stretches. Some others were getting tennis coaching on clay courts off to the side. This was clearly a children’s home, and miles nicer than Nebraska House.

There was a set of clean clothes on the floor: white socks and boxers, pressed orange T-shirt, green military-style trousers with zipped pockets, and a pair of boots. James picked the boots up and inspected them: rubbery smell and shiny black soles. They were new.

The military-style clothes made James wonder if this was where kids ended up if they kept getting into trouble. He put on the underwear and studied the logo embroidered on the T-shirt. It was a crosshair with a set of initials: CHERUB. James spun the initials in his head, but they didn’t make any sense.

Out in the corridor the kids had the same boots and trousers as James, but their T-shirts were either black or gray, all with the CHERUB logo on them.

James spoke to a boy coming towards him.

“I don’t know what to do,” James said.

“Can’t talk to orange,” the boy said, without stopping.

James looked both ways. It was a row of doors in either direction. There were a couple of teenage girls down one end. Even they were wearing boots and green trousers.

“Hey,” James said. “Can you tell me where to go?”

“Can’t talk to orange,” one girl said.

The other one smiled, saying, “Can’t talk,” but she pointed towards a lift and then made a downward motion with her hand.

“Cheers,” James said.

James waited for the lift. There were a few others inside including an adult who wore the regulation trousers and boots but with a white CHERUB T-shirt. James spoke to him.

“Can’t talk to orange,” the adult said before raising one finger.

Up to now James had assumed this was a prank being played on the new kid, but an adult joining in was weird. James realized the finger was telling him to get out at the first floor. It was a reception area. He could see out the main entrance into plush gardens where a fountain spouted water five meters into the air. James stepped up to an elderly lady behind a desk.

“Please don’t say ‘Can’t talk to orange,’ I just—”

He didn’t get to finish.

“Good morning, James. Doctor McAfferty would like to see you in his office.”

She led James down a short corridor and knocked on a door.

“Enter,” a soft Scottish accent said from inside.

James stepped into an office with full height windows and a crackling fireplace. The walls were lined with leather-bound books. Dr. McAfferty stood up from behind his desk and crushed James’s hand as he shook it.

“Welcome to CHERUB campus, James. I’m Doctor Terrence McAfferty, the chairman. Everybody calls me Mac. Have a seat.”

James pulled out a chair from under Mac’s desk.

“Not there, by the fire,” Mac said. “We need to talk.”

The pair settled into armchairs in front of the fireplace. James half-expected Mac to put a blanket over his lap and start toasting something on a long fork.

“I know this sounds dumb,” James said. “But I can’t remember how I got here.”

Mac smiled. “The person who brought you here popped a needle in your arm to help you sleep. It was quite mild. No ill effects, I hope?”

James shrugged. “I feel fine. But why make me go to sleep?”

“I’ll explain about CHERUB first. You can ask questions afterwards. OK?”

“I guess.”

“So what are your first impressions of us?”

“I think some children’s homes are much better funded than others,” James said. “This place is awesome.”

Doctor McAfferty roared with laughter. “I’m glad you like it. We have two hundred and eighty pupils. Four swimming pools, six indoor tennis courts, an all-weather football field, a gymnasium and a shooting range, to name but a few. We have a school on-site. Classes have ten pupils or fewer. Everyone learns at least two foreign languages. We have a higher proportion of students going on to top universities than any of the leading public schools. How would you feel about living here?”

James shrugged. “It’s beautiful, all the gardens and that. I’m not exactly brilliant at school though.”

“What is the square root of four hundred and forty-one?”

James thought for a few seconds.

“Twenty-one.”

“I know some very smart people who wouldn’t be able to pull off that little party trick.” Mac smiled. “Myself included.”

“I’m good at maths.” James smiled, embarrassed. “But I never get good marks in my other lessons.”

“Is that because you’re not clever or because you don’t work hard?”

“I always get bored and end up messing around.”

“James, we have a couple of criteria for new residents here. The first is passing our entrance exam. The second, slightly more unusual requirement, is that you agree to be an agent for British Intelligence.”

“You what?” James asked, thinking he hadn’t heard right.

“A spy, James. CHERUB is part of the British Intelligence Service.”

“But why do you want children to be spies?”

“Because children can do things adults cannot. Criminals use children all the time. I’ll use a house burglar as an example:

“Imagine a grown man knocking on an old lady’s door in the middle of the night. Most people would be suspicious. If he asked to come in the old lady would say no. If the man said he was sick she’d probably call an ambulance for him, but she still wouldn’t let him in the door.

“Now imagine the same lady comes to her door and there’s a young boy crying on the doorstep. ‘My daddy’s crashed up the street. He’s not moving. Please help me.’ The lady opens the door instantly. The boy’s dad jumps out of hiding, clobbers the old dear over the head and legs it with all the cash under the bed. People are always less suspicious of youngsters. Criminals have used this for years. At CHERUB, we turn the tables and use children to help catch them.”

“Why pick me?”

“Because you’re intelligent, physically fit, and you have an appetite for trouble.”

“Isn’t that bad?” James asked.

“We need kids who have a thirst for a bit of excitement. The things that get you into trouble in the outside world are the sort of qualities we look for here.”

“Sounds pretty cool,” James said. “Is it dangerous?”

“Most missions are fairly safe. CHERUB has been in operation for over fifty years. In that time four youngsters have been killed, a few others badly injured. It’s about the same as the number of children who would have died in road accidents in a typical inner-city school, but it’s still four more than we would have liked. I’ve been chairman for ten years. Luckily, all we’ve had in that time is one bad case of malaria and someone getting shot in the leg.

“We never send you on a mission that could be done by an adult. All missions go to an ethics committee for approval. Everything is explained to you, and you have an absolute right to refuse to do a mission or to give it up at any point.”

“What’s to stop me telling about you if I decide not to come here?”

Mac sat back in his chair and looked slightly uncomfortable.

“Nothing stays secret forever, James, but what would you say?”

“What do you mean?”

“Imagine you’ve found the telephone number of a national newspaper. You’re speaking to the news desk. What do you say?”

“Um . . . There’s this place where kids are spies and I’ve been there.”

“Where is it?”

“I don’t know. . . . That’s why you drugged me up, isn’t it? So I didn’t know where I was.”

Mac nodded. “Exactly, James. Next question from the news desk: Did you bring something back as evidence?”

“Well . . .”

“We search you before you leave, James.”

“No then, I guess.”

“Do you know anyone connected with this organization?”

“No.”

“Do you have any evidence at all?”

“No.”

“Do you think the newspaper would print your story, James?”

“No.”

“If you told your closest friend what has happened this morning, would he believe you?”

“OK, I get the point. Nobody will believe a word I say so I might as well shut my trap.”

Mac smiled.

“James, I couldn’t have put it better. Do you have any more questions?”

“I was wondering what CHERUB stood for?”

“Interesting one, that. Our first chairman made up the initials. He had a batch of stationery printed. Unfortunately he had a stormy relationship with his wife. She shot him before he told anyone what the initials meant. It was wartime, and you couldn’t waste six thousand sheets of headed notepaper, so CHERUB stuck. If you ever think of anything the initials might stand for, please tell me. It gets quite embarrassing sometimes.”

“I’m not sure I believe you,” James said.

“Maybe you shouldn’t,” Mac said. “But why would I lie?”

“Perhaps knowing the initials would give me a clue about where this place is, or somebody’s name or something.”

“And you’re trying to convince me you wouldn’t make a good spy.”

James couldn’t help smiling.

“Anyway, James, you can take the entrance exam if you wish. If you do well enough I’ll offer you a place and you can go back to Nebraska House for a couple of days to make up your mind. The exam is split into five parts and will last the rest of the day. Are you up for it?”

“I guess,” James said.

The Recruit

CHAPTER 10

TESTS

Mac drove James across the CHERUB campus in a golf buggy. They stopped outside a traditional Japanese-style building with a single-span roof made of giant sequoia logs. The surrounding area had a combed gravel garden and a pond stuffed with orange fish.

“This building is new,” Mac said. “One of our pupils uncovered a fraud involving fake medicine. She saved hundreds of lives and billions of yen for a Japanese drug company. The Japanese thanked us by paying for the new dojo.”

“What’s a dojo?” James asked.

“A training hall for martial arts. It’s a Japanese word.”

James and Mac stepped inside. Thirty kids wearing white pajamas tied with black or brown belts were sparring, twisting one another into painful positions, or getting flipped over and springing effortlessly back up. A stern Japanese lady paced among them, stopping occasionally to scream criticism in a mix of Japanese and English that James couldn’t understand.

Mac led James to a smaller room. Its floor was covered with springy blue matting. A wiry kid was standing at the back doing stretches. He was about four inches shorter than James, in a karate suit with a black belt.

“Take your shoes and socks off, James,” Mac said. “Have you done martial arts before?”

“I went a couple of times when I was eight,” James said. “I got bored. It was nothing like what’s going on out there. Everyone was rubbish.”

“This is Bruce,” Mac said. “He’s going to spar with you.”

Bruce walked over, bowed and shook James’s hand. James felt confident as he squashed Bruce’s bony little fingers. Bruce might know a few fancy moves but James reckoned his size and weight advantage would counter them.

“Rules,” Mac said. “The first to win five submissions is the winner. An opponent can submit by speaking or by tapping his hand on the mat. Either opponent can withdraw from the bout at any time. You can do anything to get a submission except hitting the testicles or eye gouging. Do you both understand?”

Both boys nodded. Mac handed James a gum shield.

“Stand two meters apart and prepare for the first bout.”

The boys walked to the center of the mat.

“I’ll bust your nose,” Bruce said.

James smiled. “You can try, shorty.”

“Fight,” Mac said.

Bruce moved so fast James didn’t see the palm of his hand until it had smashed into his nose. A fine mist of blood sprayed as James stumbled backwards. Bruce swept James’s feet away, tipping him on to the mat. Bruce turned James on to his chest and twisted his wrist into a painful lock. He used his other hand to smear James’s face in the blood dripping from his nose.

James yelled through his gum shield, “I submit!”

Bruce got off. James couldn’t believe Bruce had half killed him in five seconds. He wiped his bloody face on the arm of his T-shirt.

“Ready?” Mac asked.

James’s nose was clogged with blood. He gasped for air.

“Hang on, Mac,” Bruce said. “What hand does he write with?”

James was grateful for a few seconds’ rest but wondered why Bruce had asked such a weird question.

“What hand do you write with, James?” Mac asked.

“My left,” James said.

“OK, fight.”

There was no way Bruce was getting the early hit in this time. James lunged forward. Trouble was, Bruce had gone by the time James got there. James felt himself being lifted from behind. Bruce threw James on to his back then sat astride him with his thighs crushing the wind out of him. James tried to escape but he couldn’t even breathe. Bruce grabbed James’s right hand and twisted his thumb until it made a loud crack.

James cried out. Bruce clenched his fist and spat out his gum shield. “I’m gonna smash the nose again if you don’t submit.”

The hand looked a lot scarier than when James had shaken it a couple of minutes earlier.

“I submit,” James said.

James held his thumb as he stumbled to his feet. A drip of blood from his nose ran over his top lip into his mouth. The mat was covered in red smudges.

“You want to carry on?” Mac asked.

James nodded. They squared up for a third time. James knew he had no chance with blood running down his face and his right hand so painful he couldn’t even move it. But he had so much anger he was determined to get one good punch in, even if it got him killed.

“Please give up,” Bruce said. “I don’t want to hurt you badly.”

James charged forward without waiting for the start signal. He missed again. Bruce’s heel hit James in the stomach. James doubled over. All he could see was green and yellow blurs. Still standing, James felt his arm being twisted.

“I’m breaking your arm this time,” Bruce said. “I don’t want to.”

James knew he couldn’t take a broken arm.

“I give up!” he shouted. “I withdraw.”

Bruce stepped back and held his hand out for James to shake it. “Good fight, James,” he said, smiling.

James limply shook Bruce’s hand. “I think you broke my thumb,” he said.

“It’s only dislocated. Show me.”

James held out his hand.

“This is going to hurt,” Bruce said.

He pressed James’s thumb at the joint. The pain made James buckle at the knees as the bone crunched back into place.

Bruce laughed. “You think that’s painful, one time someone broke my leg in nine places.”

James sank to the floor. The pain in his nose felt like his head was splitting in two between his eyes. It was only pride that stopped him crying.

“So,” Mac said. “Ready for the next test?”

• • •

James realized now why Bruce had asked which hand he wrote with. His right hand was painful beyond use. James sat in a hall surrounded by wooden desks. He was the only one taking the test. He had bits of bloody tissue stuffed up each nostril and his clothes were a mess.

“Simple intelligence test, James,” Mac explained. “Mixture of verbal and mathematical skills. You have forty-five minutes, starting now.”

The questions got harder as the paper went on. Normally it wouldn’t have been bad but James hurt in about five different places, his nose was still bleeding, and every time he shut his eyes he felt like he was drifting backwards. He still had three pages left when time ran out.

• • •

James’s nose had finally stopped bleeding and he could move his right hand again, but he still wasn’t happy. He didn’t think he’d done well on the first two tests.

The crowded canteen was weird. Everybody stopped talking when James got near them. He got “Can’t talk to orange” three times before somebody pointed out cutlery. James took a block of lasagne with garlic bread and a fancy-looking orange mousse with chocolate shreds on top. When he got to the table he realized he hadn’t eaten since the previous night and was starving. It was loads better than the frozen stuff at Nebraska House.

• • •

“Do you like eating chicken?” Mac asked.

“Sure,” James said.

They were sitting in a tiny office with a desk between them. The only thing on the desk was a metal cage with a live chicken in it.

“Would you like to eat this chicken?”

“It’s alive.”

“I can see that, James. Would you like to kill it?”

“No way.”

“Why not?”

“It’s cruel.”

“James, are you saying you want to become a vegetarian?”

“No.”

“If you think it’s cruel to kill the chicken, why are you happy to eat it?”

“I don’t know,” James said. “I’m twelve years old, I eat what gets stuck in front of me.”

“James, I want you to kill the chicken.”

“This is a dumb test. What does this prove?” James asked.

“I’m not discussing what the tests are for until they’re all over. Kill the chicken. If you don’t, somebody else has to. Why should they do it instead of you?”

“They get paid,” James said.

Mac took his wallet out of his jacket and put a five-pound note on top of the cage.

“Now you’re getting paid, James. Kill the chicken.”

“I . . .”

James couldn’t think of any more arguments and felt that at least if he killed the chicken he would have passed one test.

“OK. How do I kill it?”

Mac handed James a biro.

“Stab the chicken with the tip of the pen just below the head. A good stab should sever the main artery down the neck and cut through the windpipe to stop the bird breathing. It should be dead in about thirty seconds.”

“This is sick,” James said.

“Point the chicken’s bum away from yourself. The shock makes it empty its bowels quite violently.”

James picked up the pen and reached into the cage.

• • •

James stopped worrying about the warm chicken blood and crap on his clothes as soon as he saw the wooden obstacle. It started with a long climb up a rope ladder. Then you slid across a pole, up another ladder, and over narrow planks with jumps between them. James couldn’t see where you went from there because the obstacle disappeared behind trees. All he could tell was that it got even higher and there were no safety nets.

Mac introduced James to his guides, a couple of fit-looking sixteen-year-olds in navy CHERUB T-shirts called Paul and Arif. They clambered up the ladder, the two older boys sandwiching James.

“Never look down,” Arif said. “That’s the trick.”

James slid across the pole going hand over hand, fighting the pain in his right thumb. The first jump between planks was only about a meter. James went over after a bit of encouragement. They climbed another ladder and walked along more planks. This set were twenty meters above ground. James placed his feet carefully, keeping his eyes straight ahead. The wood creaked in the breeze.

There was a one and a half meter gap between the next set of planks. Not a difficult jump at ground level but between two wet planks twenty meters up, James was ruffled. Arif took a little run up and hopped over easily.

“It’s simple, James,” Arif said. “Come on, this is the last bit.”

A bird squawked. James’s eyes followed it down. Now he saw how high he was and started to panic. The clouds moving made him feel like he was falling.

“I can’t stand it up here,” James said. “I’m gonna puke.”

Paul grabbed his hand.

“I can’t do it,” James said.

“Of course you can,” Paul said. “If it was on the ground you wouldn’t break your stride.”

“But it’s not on the bloody ground!” James shouted.

James wondered why he was standing twenty meters up, with a headache, an aching thumb, plus dried blood and chicken crap all over him. He thought about how rubbish Nebraska House was and what Sergeant Davies had said about his knack of getting into trouble landing him in prison. The jump was worth the risk. It could change his whole life.

He took a run up. The plank shuddered as he landed. Arif steadied him. They walked to a balcony with a hand rail on either side.

“Brilliant,” Arif said. “Now there’s only one more bit to go.”

“What?” James said. “You just said that was the last bit. Now we just go down the ladder.”

James looked. There were two hooks for attaching a rope ladder. But the ladder wasn’t there.

“We’ve got to go all the way back?” James asked.

“No,” Arif said. “We’ve got to jump.”

James couldn’t believe it.

“It’s easy, James. Push off as you jump and you’ll hit the crash mat at the bottom.”

James looked at the muddy blue square on the ground below.

“What about all the branches in the way?” James asked.

“They’re only thin ones,” Arif said. “Sting like hell if you hit them though.”

Arif dived first.

“Clear,” a miniature Arif shouted from the bottom.

James stood on the end of the plank. Paul shoved him before he could decide for himself. The flight down was amazing. The branches were so close they blurred. He hit the crash mat with a dull thump. The only damage was a cut on his arm where a branch had whipped him.

• • •

James could only swim a couple of strokes before he got scared. He’d had no dad to take him swimming. His mum had avoided the pool because she was fat and everyone laughed at her in a swimming suit. The only time James had been swimming was with his school. Two kids James had bullied on dry land had pulled him out of his depth and abandoned him. He’d got dragged out and the instructor had had to pump water out of his lungs. After that James refused to get changed and spent swimming lessons reading a magazine in the changing rooms.

James stood at the edge of the pool, fully dressed.

“Dive in, get the brick out of the bottom, and swim to the other end,” Mac said.

James thought about giving it a go. He looked at the shimmering brick and imagined his mouth filled with chlorinated water. He backed away from the pool, queasy with fear.

“I can’t do this one,” James said. “I can’t even swim one width.”

• • •

James was back where he’d started, in front of the fire in Doctor McAfferty’s office.

“So, after the tests, should we offer you a place here?” Mac asked.

“Probably not, I guess,” James said.

“You did well on the first test.”

“But I didn’t get a single hit in,” James said.

“Bruce is a superb martial artist. You would have passed the test if you’d won, of course, but that was unlikely. You retired when you knew you couldn’t win and Bruce threatened you with a serious injury. That was important. There’s nothing heroic about getting seriously injured in the name of pride. Best of all, you didn’t ask to recover before you did the next test and you didn’t complain once about your injuries. That shows you have strength of character and a genuine desire to be a part of CHERUB.”

“Bruce was toying with me, there was no point carrying on,” James said.

“That’s right, James. In a real fight Bruce could have used a choke-hold that would have left you unconscious or dead if he’d wanted to.

“You also scored decently on the intelligence test. Exceptional on mathematical questions, about average on the verbal. How do you think you did on the third test?”

“I killed the chicken,” James said.

“But does that mean you passed the test?”

“I thought you asked me to kill it.”

“The chicken is a test of your moral courage. You pass well if you grab the chicken and kill it straight away, or if you say you’re opposed to killing and eating animals and refuse to kill it. I thought you performed poorly. You clearly didn’t want to kill the chicken but you allowed me to bully you into doing it. I’m giving you a low pass because you eventually reached a decision and carried it through. You would have failed if you’d dithered or got upset.”

James was pleased he’d passed the first three tests.

“The fourth test was excellent. You were timid in places but you got your courage together and made it through the obstacle. Then the final test.”

“I must have failed that,” James said.

“We knew you couldn’t swim. If you’d battled through and rescued the brick, we would have given you top marks. If you’d jumped in and had to be rescued, that would have shown poor judgment and you would have failed. But you decided the task was beyond your abilities and didn’t attempt it. That’s what we hoped you would do.

“To conclude, James, you’ve done good. I’m happy to offer you a place at CHERUB. You’ll be driven back to Nebraska House and I’ll expect your final decision wit

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...