- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

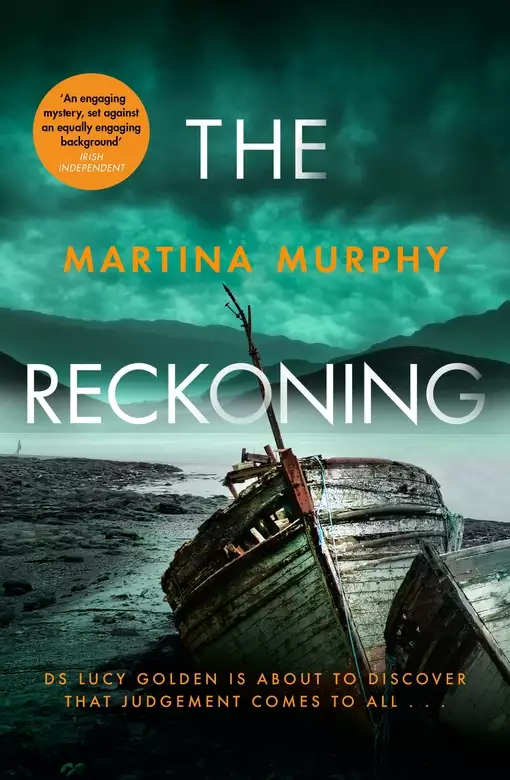

The reckoning is coming...

In an isolated house by Dugort pier a body is found. DS Lucy Golden is shocked to discover that the victim, Sandra Byrne, is a sister of one of her old school friends. To further complicate matters, Ben Lively, one of Lucy's colleagues, is the chief suspect. Lucy must put aside her bias in order to uncover the truth. But the deeper she digs into Sandra's life, the more the past starts to unravel and the less she seems to know. How do you solve a murder when all you have are lies?

As Lucy desperately tries to sort out what is true from what is not, Rob, her ex-husband and ex-con, makes a reappearance.

And when the reckoning for past mistakes finally arrives, nothing is what it seems.

Praise for Martina Murphy

'The Branded pulls you straight into the story, snares you, and won't let you escape until you turn the last page' Patricia Gibney

'A novel that raises the bar for crime procedurals. . . artful, measured and gripping' Shots Magazine

'A twisty mystery, a moody setting and a troubled cop on a tricky case. What more could you want?' Peterborough Evening Telegraph

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 85000

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Reckoning

Martina Murphy

Larry, Ben, Dan and I are at the bar, there being nowhere else to go. We’re celebrating the closing of a case that had led to the conviction of two men for assault and robbery. They’d plagued the locality for close to eight months before their granny had finally turned them in. She was sick, she declared in court, of trying to get them on the right path.

‘To the right path,’ Larry raises his pint, ‘and to Granny Ryan.’

‘To the right path,’ we chant, clinking glasses, ‘and to Granny Ryan.’

‘To Granny Ryan,’ a tipsy red-headed woman to our right shouts, having overheard us.

‘And to all who sail in her,’ someone else chimes in, amid laughter.

The redhead chortles loudly, in a frantic sort of way.

There is something familiar …

‘Lucy, d’you hear what I just said?’ Larry asks. He follows my gaze, screws up his face. ‘I’m not into redheads.’

Larry is a total player. I’m just waiting for the day when some woman will break his heart but it’s looking increasingly unlikely.

‘I doubt that redhead is into arsehole narcissists.’ I pull my gaze away from her and refocus on the lads. For some reason, while I’ve been mentally congratulating myself on my clever comeback, they’ve suddenly developed an air of nervous apprehension. ‘What?’

Larry won’t meet my gaze as he mumbles, ‘I, eh, well, hmm, Larissa McKenna died. Isn’t she the one …?’

He doesn’t finish his sentence. Instead his eyes slide right into his pint glass. I know what he was about to say. Isn’t she the one who threw acid in your face?

‘Did you draw the short straw on having to tell me that, Lar?’ I ask.

All three have the grace to look abashed.

‘I tried to tell you,’ Dan says, ‘but there was no right time.’

‘I told him to just say it out straight,’ Larry says. ‘But he’s a bloody pussy.’

‘Sorry.’ Dan winces.

‘Thank you for your sensitivity in choosing this pub to break it to me,’ I say. ‘It’s so the right place.’

‘You’re welcome.’ Larry totally misses my sarcasm.

‘You all right?’ Dan asks.

I think I am. It’s a relief to be honest. I’d known she was released a couple of years ago and had always wondered where she was. In all my years on the force, her attack had been the most traumatic thing that had ever happened to me. She’d been the wife of one of my informants who had turned state’s witness. He’d gone on to witness protection while she had refused to go, unwilling to uproot her child. She had walked into the Dublin station where I worked at the time and accused me of robbing her of her husband.

I suppose I had.

The next thing I remember was pain. Searing, burning, horrific pain. And the surgeon telling me that there was only so much he could do and that I’d have to live with a huge scar down the left side of my face.

It was as if the bottom had fallen out of my world.

‘Cancer,’ Larry says then. ‘Liver.’

‘Lucy Golden, hey!’

The voice breaks into our conversation. It’s the red-headed woman again. I should know her, I think. She’s older than she first appears, a little younger than me maybe, attractive, her hair a riot of corkscrew curls, framing a thin face with over-large green eyes. She’s wearing red jeans and a yellow top, the clothes making her stand out in this packed but dreary pub. Her make-up is bright too, scarlet lipstick that clashes with the hair.

The three men make room for her to squeeze in, Ben giving her a not-so-subtle once-over.

‘It’s me,’ the woman says, her voice bright as a new penny, ‘Sandra Byrne. Megan’s sister?’

Of course.

‘Don’t you remember? I—’

‘Yes, I remember you.’ I attempt a smile. ‘Blast from the past.’ I shift, a little uncomfortable, not sure how to broach the subject in the packed pub, but knowing I should. ‘I was so sorry to hear about your mother. I couldn’t make the funeral. My mother went, though. She said it was lovely.’

‘Thanks.’ Sandra’s bright smile dips and she blinks rapidly. ‘It was awful, totally unexpected.’ Bright smile again. ‘How are you?’

‘Grand.’

She looks expectantly at me, wanting an introduction to the lads.

‘Ben.’ He pre-empts me. ‘I’m a detective, I work with Lucy, and this is Larry and this is Dan.’ He offers her his most charming smile.

She laps it up.

‘Oh, a de-tec-tive,’ she says. ‘That must be dangerous work.’

‘It can be.’ Ben’s voice is unnecessarily grave and Larry rolls his eyes.

‘Ripe for the plucking is our Ben,’ Dan whispers in my ear.

‘Ripe for the fucking,’ I whisper back, and Dan snorts a laugh, which he quickly tries to turn into a cough. Ben is separated about two years now from his ultra-glamorous, ultra-young, ultra-pain-in-the-hole wife.

‘Ben got beaten up by an old woman once.’ Larry adopts the same grave tone as Ben. ‘A packet of frozen peas, right in the face.’

‘Piss off, that’s not true,’ Ben says quickly, with a glare at Larry. ‘He’s just messing. I was involved in that case last year when the girl was found in the suitcase in Achill.’

‘Never!’ Sandra is good, I’ll give her that. If Ben was an apple, he’d have ripened right up.

‘Let me buy you a drink and I’ll tell you about it,’ Ben says, gently leading her back to her seat. He wants us to butt out, which we do. As Larry sensitively puts it, Ben needs to get his hole and fast.

Ben doesn’t need to know that when Sandra was fifteen she’d given birth to a boy and, much to the horror of the older locals, had refused to name the father. He doesn’t need to know that at sixteen she’d got a job in a shop in Dublin and left her son with her older sister Megan ‒ my long-ago best friend ‒ and her husband. He doesn’t need to know that to all intents and purposes, according to my mother, she’d abandoned her child, never coming back for him. ‘Though,’ my mother always says, ‘Devon was probably better off. Sandra would never have been able for him with all his illnesses. And her own problems.’ Mental Sandra Byrne, she’d been christened in those less sensitive times. And it had been an apt moniker.

No, I think, Ben just needs a good time. Sandra too, maybe.

An hour later, with his arm about her waist, Ben leaves with Sandra. By ten the next morning, Sandra is dead.

Devon, her son, was the one who rang 999. I spot him as I make my way towards the scene. I tell Dan to go on ahead and I approach Devon, who is leaning against the bonnet of his dilapidated car, which nevertheless is polished to a high shine. It’s obviously his pride and joy. He’s a small man, at least a head shorter than Luc, though almost everyone is shorter than Luc. He has inherited his mother’s curly red hair, which pokes out from under his hat, and his face is nut brown from summers on the beach. He wears a thick tracksuit, a blue beanie hat and blue runners with an Adidas logo. He recognises my voice behind my mask and greets me as ‘Luc’s mother’.

‘How are you doing?’

‘All right.’ His tone is flat, eyes expressionless. Shock.

‘Me and my colleague are just going into the house now,’ I tell him. ‘That’s what this is for.’ I hold up the sealed bag containing the dust suit. ‘When I come back out, I’ll talk to you, okay?’

‘All right.’

‘I’m so sorry,’ I add.

‘My auntie Megan is on her way over.’

‘Good. Get some sweet tea into you.’ I attempt some sort of comforting smile, but he doesn’t react. ‘See you in a bit.’

I change into the suit, which is, as usual, bloody enormous. Pulling the mask on, I join Dan, who is waiting for me at the front door. ‘Are we all right to enter?’ I call out.

‘Come on in, Lucy. Dan, stay outside for now, talk to the SOCOs, see if there’s anything.’ It’s William, the DI. As senior investigating officer, or SIO, he oversees all our cases down here. A man without the ability to small-talk, he terrifies most of the team. I don’t mind him at all: I like that he’s so direct because I have to know where I stand with people and William does not pussy-foot around.

His voice comes from upstairs, and after we give our names to the garda on the scene, Dan moves to the side of the building, following the safe path marked out. I enter, mindful to step only on the plates that the SOCO team have placed on the floor. They can be slippery sometimes, especially on tiles, and I’m relieved to see that these are the metal ones, which are a bit sturdier than the plastic.

With great care, I make my way down the hall towards the stairs. Flock wallpaper, dado rails, brown pictures of hunting scenes. The smells of bacon and cabbage and stew permeate the place, but underneath is a smell I recognise, faint now but if left, it will smother all other odours with its sweet, rotten heaviness. Four brown doors open off the hall and, peering briefly inside, I catch glimpses of the SOCO team tagging and bagging anything they think might help the investigation. Unfortunately, the place appears to be a hoarder’s paradise, and while some of the rooms seem to have been cleared out into boxes, others are full of clutter. Shelves of heavy ornaments and photograph frames cover every surface. Cups and glasses and dinner plates spill from the kitchen. Empty wine bottles stand to attention just about everywhere I look.

This place will be a nightmare to gather evidence from.

Climbing the stairs, I pass boxes labelled ‘Mammy’s clothes’, ‘Daddy’s clothes’, ‘religious pictures’, ‘ornaments’. At the top, I steel myself to approach the bedroom where the body is. Through the open door, I see William standing at the foot of a bed while a garda photographer takes pictures of the body from every angle. The pathologist, Joe Palmer, has been and gone with promises to get an interim report to us by the conference this evening. He’s a cranky bastard, always ready with a barb or two. I’m glad to have missed him.

The bedroom, where the body lies ‒ or ‘the injured party’ as Sandra will be known from now on ‒ is caught in a nineties time warp. It must have been either Sandra’s or Megan’s at one time. Posters of Oasis and the Spice Girls are pasted crookedly on the swirly-patterned wallpaper. An old radio sits atop a brown chest of drawers. Heavy blue curtains, in need of a good wash, hang in the window, which also needs cleaning. A cup and glass have been smashed and lie scattered near the door.

There is a strange stillness in the space, even though the broken body of Sandra lies splayed out across the floor, face down, blood pooling on the carpet from a head wound. You don’t have to be a pathologist to guess that that’s probably what killed her.

‘Palmer says it looks like the blow to the head was the fatal wound,’ William says. ‘We haven’t found a murder weapon yet. Early indicators point to her having a tussle with the suspected offender. She tried to escape, was struck with an object, fell, and was struck again.’ He points at the walls, where the blood has made a classic impact spatter pattern. ‘See?’

‘Yes.’ I finally turn to Sandra. Last night she’d been alive, tipsy and flirty, and now, ten hours later, she was dead, her body already showing signs of rigor mortis. She looks tinier in death than she did in life and I wonder who the hell has done this and if they are still on the island.

She is barefoot, an oversized black pyjama top covering her upper body to just above her knees. I squint slightly, the better to see. ‘John,’ I call to the SOCO, ‘what’s that?’

John crosses over, leans in.

‘See there.’ I point to what looks like a reddish-brown hair on her black T-shirt. ‘See that?’

‘Try to get it, John, will you?’ William orders.

‘Good spot.’ John, using tweezers, takes the hair from the T-shirt. He turns it this way and that, before bagging and tagging it.

‘No sign of a break-in,’ William goes on. ‘This was done by someone she opened the door to or by someone who had a key.’

Shit, I think. If Sandra had been murdered in a break-in, Ben would have been in the clear. Only there hasn’t been a break-in. Shit. I have to tell William that Ben may be a suspect. ‘Cig,’ I begin, not knowing how to say it, feeling I’m betraying a man I’ve grown to know very well.

‘We need as much as we can on the IP before tonight,’ William interrupts. His gaze flits from me to take in every detail of the room. ‘We’ll have the usual team, if they’re available. I hear Matt is off in the Canaries with that Stacy one. I’ve a good mind to pay him to stay there, keep that reporter out of our hair.’

‘I’m sure Matt would oblige, Cig,’ I say. ‘They’re engaged now apparently. Look, there’s something—’

‘Marvellous,’ William interrupts again. ‘Just what we need, a guard in love with a reporter. Hopefully they’ll break up.’ He means it, too, I think in amusement. ‘Mick and Susan are available, Pat’s around, Kev’s raring to go. And Larry’s free too.’ He pauses and I wait because I know it’s coming. Without even glancing at me, he asks silkily, ‘Were you ever going to tell me that Ben was in a relationship with our IP, DS Golden?’

Shit. He never calls me by my rank. ‘Just now, only you interrupted me,’ I say, then add, a little defensively, ‘I wouldn’t actually call a one-night stand a relationship, Cig.’

‘He was the last person to see her alive,’ he says. ‘As far as we know.’

A silence develops. I fall right into the classic garda trap.

‘Yes … well, I know. I know that. But Ben? Come on …’

‘He’s going to be a suspect.’

‘Ben would never—’

‘Most people would never.’ William snaps his head around, and I cringe. ‘Most people don’t go out to murder someone, Lucy. Have you not realised that by now?’ His voice is ice. ‘Most murders just happen.’

‘That’s assuming she was murdered,’ I say. ‘She could have just tripped and banged her head off the bed or whatever. There’s a lot of wine bottles about the place.’

‘There was one by the bed.’ John speaks up. ‘Along with a glass.’

‘Point taken,’ William says, though he knows that neither of us really believes she banged her head. He turns to me, his eyes hard. ‘If you have information, you bloody well tell it sooner.’

‘Yes, William. Sorry.’

John sidles from the room, throwing me a sympathetic glance behind William’s back.

‘Get out.’ William dismisses me with a scathing look. ‘Go on. Tell Dan, if he’s finished, to go back and sort out the incident room. Make sure we have everything we need. You, go and talk to the son.’

Chastened, kicking myself for my hesitation, I give Dan his instructions and am about to change out of my dust suit when I’m approached by Louis, one of the SOCOs. ‘Come and have a look at this,’ he says, and I follow him around to the side of the house.

‘See the windowsill here,’ he says, and I notice that it’s covered with what looks like blood. At my unspoken question, Louis nods. ‘Blood all right,’ he says. ‘But it hasn’t come from inside the house, as far as I can tell.’

The whole windowsill is covered with it, almost like it was poured on. How weird. ‘Can you take a sample of that as soon as possible, Louis?’

‘Yes. We’re on it.’

‘Thanks.’ Disposing of the dust suit, I head towards Devon. Someone has given him a tea, but he’s not drinking it. Instead, his gaze is focused somewhere beyond the house, across the brown-gold scrubby landscape to the rise of the hill, dark against the grey sky. There is loneliness in the image he presents. A biting wind sweeps in from the Atlantic, and the sound of the waves slapping against Dugort Pier is carried across on the air. It’s desolate. This is a road travelled only by those using the pier and by the few people who live along this stretch. It’s just a step up from a narrow dirt track. The pier itself is tiny, functional. I zip up my jacket against the chill.

As I approach him, Devon is joined by a stout woman, who lightly presses his arm. It makes him flinch, liquid slopping over the rim of the mug onto his hand. The woman gently takes the tea from him, setting it on the ground, before wrapping him in her arms, whispering to him. He looks stiff in her embrace, but she holds him hard. Then she pulls away and stares into his face, says something else and he signals agreement.

It’s Megan, I realise. Sandra’s sister and my teenage friend. She’s got plump and round and … the only word I can think of is womanly. Her clothes are square, a big square black padded jacket, black trousers with straight legs. Functional black shoes. Her hair is buried underneath a black hat, which is pulled down low over her forehead. She looks like the person she was always going to be. Sensible. Homely.

I wait a moment, observing, then cross towards them. ‘Hello,’ I say. Then, ‘Megan? I’m so sorry for your loss. Losses,’ I amend.

Megan releases Devon and turns to me. There is such savage sadness in her eyes that I feel suddenly ashamed of myself for losing touch with her. ‘Thanks,’ she says. A pause, before she turns to Devon saying, ‘Devon, this was my best friend in school, Lucy Golden.’

‘Luc’s ma, I know,’ he says. ‘Luc was in my school.’

‘And your aunt and I, we were good friends.’ I half smile. ‘Megan, can I talk to Devon? You can stay if you like.’

‘You want to talk to him here?’

‘If you don’t mind. The sooner we get a statement the better. It’s surprising how things get forgotten with shock and that, you know.’

‘Of course.’ Megan shoves her hands into her overlarge jacket. ‘Are you all right with that, Devs?’

‘Sure.’

‘I just need you to take me through how you found the … how you found your mother.’ I pull out my notebook and pen and look at him.

He drops his gaze before removing his hat and running a stubby hand through his hair. ‘I just came to help with the clear-out,’ he mumbles.

‘Clear-out?’

‘Mammy died a week ago,’ Megan explains. ‘We’ve been clearing the house out to sell it. Sandra was helping. She said she’d stay until it was done.’

‘Of course.’ That explains the boxes. ‘I’m sorry I didn’t make your mother’s funeral,’ I say. Then I add, because it’s expected, ‘My mother says it was a lovely one.’

‘It was,’ Megan agrees, swallowing hard. ‘She would have approved. All her favourite hymns and that.’ I watch her battle back the tears. ‘Sorry,’ she apologises, flapping a hand. ‘I still can’t believe … and yet she was old, not in the best of health. I mean, it was almost a relief when she died, in a way, not that I don’t miss her,’ she tacks on hastily. ‘But Sandra … that … that is—’

‘A relief too,’ Devon says flatly, and Megan flinches. He looks at me and his eyes, green like his mother’s, are desolate. ‘It’s just hypocrisy to pretend we’re sad about it. It is a relief.’ A tear slides out of the corner of his eye. He doesn’t notice. ‘I mean, she came back for the funeral and then caused trouble at the afters.’

My mother had mentioned nothing about trouble.

Megan is at a loss as to what to say. After a moment, she shrugs, says to me, ‘You know what Sandra was like.’

‘Not really,’ I answer. ‘But maybe you’ll be able to tell me. For now, though, Devon, can you go through the events of earlier? Tell me as much as you can remember. What time you arrived, how you got in, what you did, all that sort of thing.’

He shivers, twists the hat in his hands, ‘Em … I got here, eh, about ten, because there was loads of work to do. My nan had a lot of stuff in that house and Auntie Megan and me, we were sorting it into boxes. Sandra was meant to help but she wasn’t, said it was too upsetting.’

Sandra, not Mam. Interesting.

‘It was better that way, pet,’ Megan says. ‘You know that.’

Devon flicks her a look but doesn’t acknowledge the comment. ‘So, I got here about ten and I went in and she wasn’t up and I called out to her to see if she wanted tea and there was no reply and, see, she was normally all over me because she thought by being nice to me it would make up for dumping me when I was a kid and—’

‘Devon,’ Megan chastises gently, looking a little alarmed.

‘Don’t!’ Devon snaps at her. ‘Just don’t.’ They eyeball each other until, finally, Megan slumps a little, which he takes as his cue to continue. ‘Like I said, she was normally all over me, and when she didn’t answer, I knocked at her bedroom door and looked inside and …’ He stops. This time it’s a while before he says softly, ‘And there she was.’

He looks at me.

‘How did you get into the house, Devon?’

‘Sorry, front door. I had a key.’

‘And you say you just found her. What did you do then?’

‘Nothing. Like … I knew … I knew she was dead, see. It was … like … obvious, so I did nothing. Just called the ambulance and the guards and that.’ He shudders. Squeezes his hat harder.

‘All right. Can you remember, Devon, if you saw anything unusual this morning on the way here or even in the house?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Anything disturbed in the house? Anything missing?’

He winces. ‘There’s a lot of stuff.’

‘Fine. One of our members will be in touch to show you some pictures of the house and contents. See if you can spot anything that might look amiss. Or things that are missing.’

‘There was so much,’ Megan reiterates. ‘We might not know.’

‘Just try your best. Now, could either of you tell me if there was anyone who would want to harm Sandra?’

‘We barely knew her,’ Devon says, bitterness laced with un-acknowledged grief. ‘She wasn’t exactly in our lives. She had bigger fish to fry than her own family, that was for sure, and—’

‘Devon,’ Megan says, almost like she could cry. ‘Just … don’t. Please.’

He gives her a look that I can’t quite fathom before shaking his head and walking off. We watch him go, pulling his hat back on, zipping up his jacket and striding away towards the road.

‘He gets upset,’ Megan says. ‘And he’s right, he didn’t really know her.’

‘How was she since she came home?’

‘Difficult,’ Megan answers, with a hint of bitterness. ‘Like she always was. You know yourself.’

‘What she was like years ago has no bearing on what she was like today,’ I state firmly. ‘I barely remember her. So, tell me, what was she like? Explain why she was difficult.’

Megan flushes slightly under the rebuke, but the truth is, I can’t have what I knew of Sandra colouring this case. I can only work on what I have now. It’s why I should have told William about Ben before I’d even got to the scene. ‘She was … selfish for one,’ Megan says. ‘She only came swanning back to see what she could get out of Mammy’s death. Oh, she was upset, too, but it was the money she came for. She caused trouble at the afters. I don’t know if it was drink or what but she verbally abused Dom, started interrogating the new priest on religion or something. Maudie had to take her home. I mean, for Christ’s sake.’

I haven’t met the new priest, but apparently, he’s a fine thing. My mother said that if the Church was hoping to get the young girls back, they were going the right way about it.

‘Any reason she might have abused Dom?’ Dom is her uncle, her mother’s brother.

‘Sandra doesn’t need a reason.’

I wait, see if she says any more.

‘You’d have to ask Dom, I don’t know.’

‘All right. So is it fair to say that neither you nor Devon welcomed her back?’

‘I was glad to see her,’ Megan says, a bit defensively. ‘Relieved, if I’m honest, because we never knew where she was. Oh, she sent us her address from time to time but didn’t phone us or …’ a flush ‘… answer our calls. I think Devon, though you’d have to ask him, I think he’s embarrassed by her. But he loves her too, I’m sure,’ she adds hastily.

‘And you’re positive you don’t know if anyone would want to harm her?’

‘She tended to annoy people so …’ Her voice trails off. She looks towards the house and shudders. ‘I don’t know.’

‘Did she say anything about her life beyond here?’

‘I think she was working in a shop, but I get the feeling that she’d ditched it ‒ she seemed determined to stay here for a while. To be honest, I’ve only seen her a couple of times since Mammy’s funeral. I’m just … well … I was just so angry at her for the afters. Maudie saw her more than me ‒ she might know more.’ A moment, before she adds, ‘Once or twice she helped with the packing up but most of the time she was out gallivanting, drinking her head off, bringing men back. She fell a few days ago, Maudie said, so Leo put a solar light in the garden. Not that she gave him any thanks. I don’t think she even noticed. And have you seen the mess the house is in? She never tidied. Mammy would have been so upset to see her house in that state.’ Then she stops, covers her mouth with her hand. ‘Oh, God, I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.’ A sudden tearing up.

‘It’s all right.’

‘She was my sister. My baby sister.’ And she starts to cry, shoulders shaking, little black hat bobbing up and down. ‘I don’t know how it got to this. I did love her.’

I’m swamped with pity for her: she looks so forlorn, hunched . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...