- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

1720. Escaping the gallows, Anne Bonney, theinfamous pirate queen, sets sail in search of a fabulous treasure said to behiding in a lost city of bones somewhere in the heart of Africa. But what she finds is a destiny she never expected . . . .

1870. Maude Stapleton is a respectable widow raising a daughter on her own. Few know, however, that Maude belongs to anancient order of assassins, the Daughters of Lilith, and heir to the legacy of Anne Bonney, whose swashbuckling exploits blazed a trail that Maude must now follow—if she ever wants to see her kidnapped daughter again!

Searching for her missing child, come hell or high water, Maude finds herself caught in the middle of a secret war between the Daughters of Lilith and their ancestral enemies, the monstrous Sons ofTyphon, inhuman creatures spawned by primordial darkness, she embarks on a perilous voyage that will ultimately lead her to the long-lost secret of Anne Bonney—and the Father of All Monsters.

Oneof the most popular characters from The Six-Gun Tarot and The Shotgun Arcana now ventures beyond the Weird West on a boldly imaginative, globe-spanning adventure of her own!

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: June 27, 2017

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

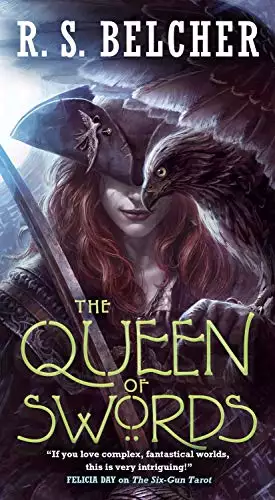

The Queen of Swords

R.S. Belcher

The Devil (Reversed)

Port Royal, Isle of Jamaica

June 11, 1721

She swore an oath that the child would be born in freedom. The baby’s first breath would not be in the stinking air of the Marshalsea Prison, even if it took her last breath to see to it. The English guard had been true to his bargain, and that made it worth the pain. His price for the secret of escape, for looking the other way, was the gold in her mouth. She had ripped the back tooth out with her bare hands. After months of starvation, and, before that, a bout of scurvy on Jack’s ship, it was easy, and that pain was nothing compared to the contractions.

The trapdoor was where the guard had said it would be. It led to a small tunnel—a simple storm drain, designed to slow the overflow of seawater if yet another hurricane hit the island. She crawled through the damp darkness, unable to drag herself on her belly anymore with the baby, so she did it on her side, pausing every few feet in the pitch blackness to gasp in pain, and curl up as best she could as another contraction wracked her body. They were coming closer together but her water had not yet broken.

After what seemed an eternity, she caught sight of moonlight beyond the grate at the end of the drain. She heard the sweetest sound she had ever known: the crash of the waves, the hiss of the sea foam. The ocean did what it always did: it promised freedom.

The storm drain’s grate was loose in the crumbling mortar channel just as she had been told. If she were her old self, she could have kicked it free easily, but starvation, illness and the child in her belly had all conspired to sap her strength. She gripped the bars and pushed, then pulled, with all her might. She was so damned weak now. It made her angry.

As she gritted her teeth and struggled with the bars between her and the welcoming sea, that snotty bastard, Willie Goode, forced his way into her mind. He had thought he could have her, right there in that alleyway in Charleston. He was sixteen and she was twelve. He outweighed her by a good fifty pounds, the slobbering, full-gorged lout. He had pinned her and began to pull at her skirts. The pressure of him on her, the sour smell of his breath, and her heart was like a hare, thudding, kicking in her chest. He was so strong, so insistent, like his pego poking her stomach. She remembered London, what had happened there, and bit off Willie’s ear. When he screamed and rose up she drove her knee into his bollocks and was satisfied when she felt a pop. It took two grown men to pull her off the sobbing little git.

She wouldn’t let the bastards win then, and she had no intention of doing it now. With a final grunt and gasp, she tore the bars free. They fell with a dull thud to the ground, and her arms loose, like rubber, fell with them. Her water broke then and she knew she didn’t have much time.

The pain was intensifying. She crawled out of the pipe and let the cool, damp air of the beach caress her like a lover. It took great effort, but she stood, resting her hands on her knees for support. A contraction knifed through her, taking her breath away, but she refused to fall. She staggered across the wet, packed sand toward the tumbling waves. She stood at the edge of what the sea had claimed for itself; the rushing foam tickled her dirty, scabbed feet. She looked up at the moon, as swollen as her own belly. She smiled at the pockmarked orb burning silently with ghost light, its scars and wounds making it even more beautiful. “Good to see you too, luv. Been too long,” she whispered.

The water covered her feet now and grabbed greedily at her ankles as it sped past her. Tide was coming in, the sea’s way of telling any sailor worth his salt it was time to move on. The pain came up sharp and sudden; it made her feel as if she had to void herself. She breathed through it. The wind and the surf were her midwives. She gulped in air when the birth pain passed. She tasted blood in her mouth where once there had been gold.

She wandered farther out into the water, up to her waist. For a moment she thought of the nasty saw-toothed sharks—the wee ones—that prowled the shallows, eager for a tasty leg to claim. But after the night she had endured to be here, she knew she could wrestle any fucking shark and win, and probably claim a bite out of it too, she was so hungry.

The pain came again, like her insides knotting and trying to spill out of her hat. She gave a little shriek but muffled herself; the water lapping against her belly was helping. She began to time her breaths to the rhythm of the tide. She had once acted as midwife, along with Mary, to a hostage off a Dutch sloop. Neither of them knew a fucking thing about delivering a kid, but Calico Jack figured since they were both women it was instinctual or some such shit. She recalled that breathing through the pains seemed to help, and pushing—pushing was good—but Mary had argued with her that the girl had to wait to push. “Wait for fucking what?” she had said. “A goddamned invitation?” In the end it hadn’t mattered whether she pushed or not. The baby came on its own. It lived a few breaths longer than its mother.

There was a shiver down her spine as the pain stabbed her again, and then again, coming closer and stronger with each passing moment. The urge to push was maddening. The waves smashed against her and still she stood her ground; the cold water splashed across her face, the sea pulled at her trying to draw her deeper into its embrace, and still she stood.

She raised her head to scream; she forced her eyes wide open, looking up at the mute moon and the uncaring stars. In this moment she was the universe—her, a petty thief, a liar, pirate, adulteress, murderess. In this final effort of breath, she was a goddess, the creator, and all the cogs spun in the heavens just for her.

The baby arrived beneath the dark churning waters of Mother Ocean, and she did not fall; even as her knees buckled and her legs became like seaweed, she remained on her feet. The child arrived swimming, vibrant and hale. She gathered the infant up in her arms. As it broke the surface, the child snorted the saltwater from its tiny nose and let loose a scream, an angry howl of protest at life itself. She laughed as the baby spit, and cried.

“Ah, marriage music,” she chuckled. “You go right ahead and get it out, wee one. This might be your first, but it sure as hell won’t be your last cry.”

She held the child up to examine and tsked when she saw the tiny penis. “So, it’s a boy you are then. Well, lucky you, lad! This chamber pot just got a little rosier for you with that twig between your nethers.” She laughed and pulled the baby to her bosom, spinning and trying to dance in the waves. She was dizzy and weak but she also felt high, like she had been smoking the poppy. She hummed a tune from her childhood in Cork, “Molly Brannigan.”

The baby screamed then slowly calmed himself. “I know,” she said, “as a singer, I’m a bloody fantastic dancer.” He nuzzled into her small breasts and she helped him find a nipple. The child drank eagerly and she could feel him sigh and relax in contentment. “Not much of a meal, I’m afraid, wee lord,” she said. “My milk’s gone dry from my stay in the governor’s digs, but take what you can.”

She looked at the tiny squirming thing in her arms and for a long moment she considered forcing it back under the dark waters until it was still. It had no life worth living at her breast, that was sure and true. She thought back to all that had come before this in her life, and how often she had prayed to never have been, yet here she was. She recalled hearing Mary’s screams a few cells down from her only a month ago, as her own baby arrived. After a time there were only the baby’s screams and Mary was silent. Eventually guards came and took the child and Mary’s body away.

She and Mary had both pled their bellies after the trial when they had been captured along with the other survivors of Calico Jack’s crew. But Mary had found her way to Hell anyway, and she knew it likely that if she tried to flee with a baby at her hip, she would soon be at Mary’s side again. So all reason, all her instincts, told her to drown the child and be on her way.

She glanced up at the moon again. The heavens were no help at all, as silent in their regard as they were beautiful. She sighed and looked down to the face of the baby boy. “You have any notions on this?” she asked. He grunted and released his first shit, dropping it in the ocean. “I couldn’t agree more, lad,” she said with a smile. “How could I drown anyone who already has such a perfect understanding of how all this works?”

She bit the birthing cord free as she walked slowly back to shore, the taste of the infant’s blood mixing with her own, and the brine of the sea, in her mouth. She spat and tied the cord off with a reef knot, muttering as she did, “Right over left, left over right, make a knot both tidy and tight. There you go—your first sailor lesson, my wee lord.”

She was exhausted, cold and starving. She needed to tend to those things and she needed to be off this accursed crown-kissing island by dawn. She tore at her filthy gown and used the fabric to clean and swaddle the baby. Off to her left, down the cove, she could see the silhouette of a town against the brilliant moonlight. There she would find roast pig, and bread and cheese and bitter grog and wine, sweet, sweet wine, and a proper bathtub, and loot, and sails to take her away from here. But first she would need to find steel, and with it gold, to make all the other things possible. She hefted her son, headed toward the sounds and smells of the port and plotted her first crime with her boy as an accomplice.

* * *

It was the devil’s hour when she entered the common room of the Witches’ Wrath. The Wrath was built on top of the corpses of the taverns Port Royal had once had in the golden days before piracy was outlawed on this island, and before the great earthquake had destroyed most of the city. The righteous claimed the quake was the anger of God Almighty, sweeping away the pirate nation and all their blood money had created. She knew well enough, though, that God annihilated saint as easily as sinner and didn’t give a fuck where the tithe came from.

The stink of the place—pungent human smells, the fetor of old ale, all poorly hidden behind the sickly sweet vapors of burning clove—was familiar to her. To her surprise, she found she had missed it, missed the parrots squawking as they drank their fill of ale from discarded flagons, missed the chattering of the monkeys and the booming laughter of the sailors, the tittering of the wenches. A good tavern was all of life on display, a sweating, mumbling, drinking, fighting, fucking museum.

She had acquired clothing—warm breeches, decent, if somewhat-too-large boots, a tunic and a vest. Her greasy red hair fell well below her shoulders. She wore a cocked hat she had crimped off the same fine fellow who had donated the rest of her clothes—he wouldn’t be needing them anymore. She wore the tricorne low, to allow the shadows to hide part of her face, but she made no attempts to pass for a man at present. Her sleeping son was strapped to her chest in a sling she had fashioned from her prison gown. She carried the dead man’s steel, a heavy and well-worn machete, in one hand, and rested the palm of her other hand on the butt of the pistol hanging from the wide sash wrapped about her waist. There was a subtle change in the current of conversation when she entered. Eyes flicked to rest upon her, sizing her up as a victim, weak and ready to be culled, or as one of the hunters. When she felt the attention, sensed the menace, she smiled a little. She was home.

“Port,” she said in the cant, the secret language of the old pirates. She dropped a few Spanish reales on the bar. The tavern keep frowned; then his face lit with surprise, and she knew he had recognized her. He slid the bottle to her. The tavern keep smiled. She saw most of his teeth were black or absent. He deftly pocketed the coins.

“Glad ta see you avoided gitting noozed,” the keep replied in the cant. “Din’t think they could git a rope about that pretty neck, Lady Calico. Too many brains in that skull of yours for the rope to fit about it. Sorry ta hear about your man’s demise.”

She took a long draw off the port. It was the sweetest thing she could recall after a year of stale water and maggoty bread. She wiped her mouth with the back of her hand. “Shit,” she said. “I told Jack I was sorry to see him in the gallows with his lads, but if he’d fought like a man, he wouldn’t have had to hang like a dog.” The tavern keep had a laugh like a cannon going off. “Herodotus Markham? Where is he?” she asked. The tavern keep nodded toward the rear room. An old man with a mane of gray hair, and a tattered red velvet coat, sat on a bench, smoking a pipe.

“Makes his way here every few nights,” the keep said. “He’s dying, but it’s a slow kind o’ dying. Still the smartest man I ever knew—not that all skull music will keep him breathing one more day.”

She slid more silver to him, “For your service, and your silence.” The keep nodded and the coins vanished. She took the bottle and headed for the back of the tavern. A dirty hand shot out of the darkness as she walked past a table of men, grabbing her. “How much you selling the brat for, luv?” Her blade was at the man’s throat before the utterance had finished leaving his lips.

“A damn sight more than I wager you’re willing to pay,” she said. The hand slipped back into the smoky darkness.

“I told you it was her, ya tosspot!” she heard one of the other sailors hiss as she walked on. “Yer damn lucky she didn’t lop your sugar stick off.”

Herodotus Markham looked as he had when she had last seen him just before she, Jack, and Mary had stolen the William. He resembled an old country squire—a gentleman of means who perhaps had fallen on hard times, or maybe had been laid upon by ruffians. His white wig was in disarray with faded ribbons of red still grasping on for dear life to the tail of it. His velvet coat was a deep burgundy marred by stains, faded by the sun and the salt of the sea. The coat had burnt patches and every cuff and collar was frayed. His face sagged like a half-empty sack of potatoes. His florid complexion was a combination of old rouge and too much drink. The only part of him that wasn’t sad was the wicked steel glint in his dark eyes. It was the last place anyone would care to look and the only place that told you this broken-down old man was still very dangerous.

Markham’s face lit up when he saw her. “Rough with black winds and storms,” he recited, “unwanted shall admire.”

“Always charm with you, Dot,” she said, sitting down next to the old man. He hugged her and she returned it. Markham gasped as the baby made a cooing sound from his hammock across her chest.

“A babe!” he exclaimed and she couldn’t help but laugh at his surprise and delight. “Oh my sweet girl! Is it Jack’s?”

“That’s the prevailing theory,” she said, adjusting the infant in his snug hammock. “Best I can figure he would have been conceived just before we took off with the William, or maybe on her.”

“If it was on ship that makes him a true son of a gun,” Markham said, “a sailor-born, just like his mother.”

“I wasn’t conceived on a ship,” she said, taking a long pull off the bottle of port, “more likely the scullery maid’s closet. Da gave Ma the goat’s jig in between her changing linens, sometimes during.”

Markham puffed his long churchwarden pipe and shook his head. “No,” he said, a wreath of tobacco smoke preceding his words “if ever I met someone born to the tides, it was you, Annie. You’re more a sea dog than old Calico Jack, Charlie Vane, or any of their ilk.”

She laughed. “One big difference,” she said, “I’m still breathing.”

“It’s the end of the golden age of the freebooters, lass,” Dot said. “The world will be less legendary, less wild, without them. We’re replacing pirates with politicians.”

“I always found pirates to be a damn sight more honest,” she said. “They tell you up front what they’re going to steal from you.”

The old man chuckled. It turned into a dry, booming cough. “Come to say good-bye, have you, girl?” She knelt and took the old man’s hands in her own.

“Yes, I have to be gone by first light. I need one last favor from you, Dot,” she said. “That chest Jack left with you before we took the William, do you recall it?”

“Aye,” Dot said. “The queer one, painted up with all those strange marks on it. Oh, yes, I recall it well. Sometimes … sometimes at night, I think I hear … singing coming out of it.”

“Singing?”

“A strange language, one I’ve never heard,” he said. “It sounds like a lot of voices, like women.”

“I need it,” she said.

“Of course, love, but are you sure? There’s something damned in that box—it’s the devil singing,” Dot said. “It makes me dream of some steaming, scorching place—of unforgiving heat, of a city made out of … dead things. I think I dreamt of Hell.”

“That box is this baby’s birthright and the final share due me from Jack,” she said. “It will lead me to a big enough score to lay down my sword. Can you fetch it for me, Dot?”

“Of course. Meet you here before dawn?” he asked. She stood and helped the old man to his feet as she did.

“No,” she said. “The north docks, near Fort James and the custom houses.”

“Done,” he said and headed for the door without another word. She got the impression Herodotus was glad to be ridding himself of the box and wanted to waste no time doing so.

She sat back on the bench and took another long sip on the bottle of port. The box was not natural—she knew that—had known it since she and Jack had taken it from the cargo hold of that merchantman headed back to England from Africa. One of Jack’s crew, a Spaniard named Thiago, had jumped from the crow’s nest onto the deck below, screaming of a city of monsters that was eating the dreams out of his skull. He screamed a name as he took his fatal plunge—“Carcosa.”

Both she and Jack had awoken from dreams of the necropolis squatting still and silent in the middle of some verdant, primal place. When they made it to port, they had consulted the smartest man either of them knew—Herodotus. He had no wisdom for them, but promised to keep the box safe.

She never told Jack but she, alone, had a final dream of the bone city. In it she stood in a sunbaked courtyard, vast like an arena. The floor of the place glittered with rubies, millions of them. She stood before a shining statue of a woman, flaring with the light of the bloated red sun. The statue was at the center of the arena, and was made of gold and ivory, diamonds and other precious stones, a king’s fortune a hundred times over, or a queen’s.

She was going to find that city and claim its treasures and its secrets, and she knew, she knew the first step on that path was the box, and then to head for Africa, from which it hailed. Now, sitting alone in the noise and life of the Witches’ Wrath, she recalled the eyes of the statue in her dream. They were terrible, the immortal gaze of a goddess—regarding her, judging her with eyes darker than a murderer’s soul, burning red at their core, hotter than any earthly forge.

She rubbed her eyes, and pushed the memory out of her mind. She realized then how much she wanted a pipe and some good tobacco.

“Now,” she said to the baby slumbering at her breast, “what do I do with you, you little snapper?” She noticed a man sitting alone at a table writing with an inkwell and pen in a ledger, occasionally popping his head up to look about, or to drink from his tankard. He was a slender man, his hair and beard the color of wheat. She rose, and moved toward him.

“Nate?” she said. “Nate Mist? I’ll be a fussock, it is you!” The man turned, frowning at first, but then broke into a wide smile once he recognized her.

“I heard your neck got stretched, Annie,” Mist said. She raised the port in salute and Mist raised his tankard.

“Haven’t found a rope clever enough,” she said. “I’m surprised to see you here. I heard you were back in England—a writer they said.”

“Publisher,” Mist replied. “Oh, and down here I’m going by Charles Johnson these days—Captain Charles Johnson. Ran into a spot of trouble back home. Thought I’d travel a bit and see if I could finish my research on the history of pirates I’m writing.”

“Well, ‘Captain,’” she said, laughing and taking another drink, “I’m a walking, talking expert on that lot.”

“That you are,” Mist said. He flipped to a fresh page in his ledger and dipped his pen in the inkwell. “Let me ask you about…”

“You’ll make a pretty bob off me and all my dead mates, won’t you, Nate?” Mist began to answer, but she waved her free hand to dismiss his reply as she sat at his table. “I’ll give it all to you, mate—you were always a good lad back then—always an honest sea dog. I’ll tell you the tale of the last days of Calico Jack and his crew. How old Eddie Teach supped with the devil and stole some of his cursed gold for himself. I’ll tell you the story of how we came across this great metal vessel the size of a hundred galleons! How it traveled under the waves and was captained by a mad genius.”

Mist leaned forward, frantically scribbling in his ledger.

“I’ll tell you the time I was stricken by the black mark—the one all pirates fear,” she went on, knowing she had Mist now, her eyes locked on his, her voice weaving her stories tight about him, “and how I had to filch wine from Neptune himself to dodge that curse. You want to know about the island where immortal cannibal children are led by a ten-thousand-year-old boy who has no shadow? I’ll give all the secrets of the pirates and the worlds they’ve been brave enough to sail through to you and you alone—enough for a hundred books—but first I want you to swear an oath to me, and do me a service, Nate. I want you to swear it on that god of yours that keeps getting you in so much trouble back home.”

“What’s the favor, Anne?” Mist asked.

She set the bottle on the table and slid her arms around and under the baby. “This,” she said. “Take him to my da in Charles Town, Oyster Point.”

“Carolina? The colonies?” Mist said. “I was thinking of sailing north in a few days. Why don’t you just go yourself?”

“I have something to tend to first,” she said. “You tell my father to keep him safe and I’ll be along once I’m finished.” She placed a bag of coins before Mist on the table. “For him and for you. Do you swear you’ll keep him safe and deliver him to my kin?”

Mist looked at the baby’s face, then to hers. “I swear it,” he said. They spit in their palms and shook to seal the oath. “Now,” she said, “let me start by telling you about the Secret Sea.…”

* * *

Night was unraveling in the East; threads of pink, orange and indigo frayed where the sky met sea. Herodotus hobbled along with the small chest. Sailors, eagerly preparing to leave with the morning tide, darted past the old man. There were shouts, curses, songs and orders in a dozen languages, all along the crowded row of docks and piers. Markham turned to look about and found himself facing a slender sailor, a man, his face shadowed with dirt that hinted at a beard. His long red hair was tied in a ponytail, the rest under a cocked hat. He wore a vest and tunic, a heavy blade and pistol held fast by a sash around his waist, breeches and boots. A ditty bag was hung over the man’s shoulder. The sailor smiled and Dot finally recognized her.

“You’re damned good at that, lass,” he said, keeping his voice low. She laughed and even that had a rough, male sound to it.

“Lots of practice.” She nodded to the box. “Thanks, Dot.” He handed her the oddly painted wooden cask and she held it with both hands. “My ship is off in a few moments.”

“You be careful with that twice-damned thing,” Herodotus said. “Where’s the boy?”

“Safe and on his way to my family in the colonies,” she said. “Here,” she said, handing him a purse full of coins. She had managed to increase her dwindling stolen stakes with a few games of bones on the docks while waiting for Dot. “There’s a ship leaving later today for the Carolina colony,” she said. “You remember Nate Mist? He’s a passenger aboard, and I’ve secured you passage as well. Nate has my boy, taking him to my da. I’d consider it a kindness if you’d accompany them and see to my boy until I return.”

“Nate’s a good man,” Markham said, nodding. He took the purse. “Very well, perhaps the change in climate will be good for what ails me.”

“Thank you,” she said. “And don’t worry. I’m taking this thing home, scoring one last haul of loot, and then I’m quits with this freebooter life.”

Herodotus laughed until he began coughing again. “I’ll believe that when I bloody see it,” he said. “You’re born to this, Annie, moon and tide, steel and gold.”

“Well, I’m retiring to be a proper lady,” she said with a grin. “One of goddamned means, to boot. Good-bye, Dot. Take good care of yourself and my lad.” They shook hands and she began to head for the gangplank of one of the ships.

“And good luck to you too, Lady…” Herodotus paused. “Anne, what the hell do I call you now? Lady Rackham? Cormac? What?”

She turned and gave the old pirate sage a wink. “I always liked my married name,” she said, “liked it better than I liked the fucking marriage. I’ll stick with that one, I think.”

“Fair enough,” Herodotus said. “Then good luck to you, Lady Bonny.”

2

The Queen of Swords

Northern Utah

December 5, 1870

(One hundred and forty-nine years later)

The train rumbled through the badlands, the ancient, snow-silvered mountains indifferent to its blustering advance. The Transcontinental Railroad was the great artery, the road connecting civilization to the wilderness, to the frontier.

With the planting of a single golden spike, a flurry of speeches, pomp and circumstance, the track had been made whole, and the gateway to the mythical West swung open. Alter Cline, sitting in the mostly empty passenger car, foresaw the railroad’s recent completion as a harbinger of death for that very myth.

Cline was twenty-four. His black hair fell to his shoulders in ringlets, parted on the side. He sported thick, stylish sideburns. Alter possessed a wiry, slender build with long legs. He stood a hair over six feet. His brown eyes were expressive and intelligent, and currently they were fixed on the striking woman sitting near the center of the passenger car.

The woman was traveling unchaperoned, which was queer. She was quite unaware of his notice, Alter was certain. Her hair was auburn, shot through with red-gold and silver strands. It was long, but she wore it up, away from her face, in a tight bun. Her skin was pale, her wrists small and delicate. Her figure was slight, and her overall appearance not the sort that would capture a man’s second glance in a crowd or a busy street. However, there was something—something that hid in this woman beneath her surface appearance. Alter enjoyed the mystery, the parlor game of guessing who she was, why she was here, where she had come from.

The mental exercise helped Cline take his mind off his unease that this untamed place, this magnificent frontier, was living on borrowed time. He was happy to be headed back to New York, but there was a freedom, a spirit awake in these wild lands, something that slept in a lot of people back East. He’d miss that rawness, that primal feeling once he was home—not that there weren’t a few neighborhoods in New York City that he was sure the toughest cow-puncher or gunslinger would find daunting.

It troubled him to think that when this frontier was gone perhaps that raw part of the human spirit would die with it. However, what he had witnessed out on the plains suggested that the same old human stains—greed, cruelty, callous indifference—traveled hand-in-hand with our primal selves wherever, whenever we go. It gave him grim reassurance that mankind was far from domesticated just yet. It made Cline wonder, too, that perhaps “civilized” people didn’t respect the freedom and the splendor out here enough to deserve it, or keep it.

He had been sent out by his editor to cover the brisk expansion in the business of buffalo skinning, as a perfect example of man’s knack for destroying wonder. It wasn’t truly buffaloes that blackened the plains in their vast numbers, that made the ground shudder like thunder in their passing, but bison. Not that those killing them in the hundreds of thousands and leaving their skinned corpses to rot on the plains, leaving sun-bleached mountains of wide, horned skulls, cared a damn about the semantics of what they were killing.

Alter had ridden out with a skinning crew for several weeks, chronicling their lives and gory, lonely work. He had lived and worked as one of them, though they joked he had no stomach for it. The demands for the hides back East were bringing more and mo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...