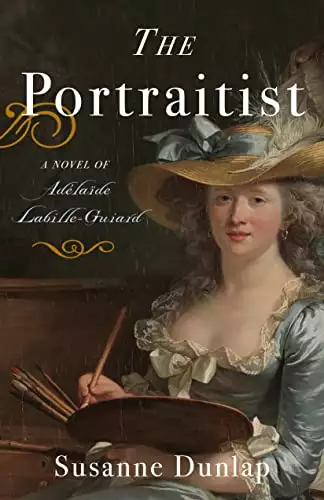

The Portraitist: A Novel of Adelaide Labille-Guiard

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Based on a true story, this is the tale of Adélaïe Labille-Guiard’s fight to take her rightful place in the competitive art world of eighteenth-century Paris.

With a beautiful rival who’s better connected and better trained than she is, Adélaïde faces an uphill battle. Her love affair with her young instructor in oil painting gives rise to suspicions that he touches up her work, and her decision to make much-needed money by executing erotic pastels threatens to create as many problems as it solves. Meanwhile, her rival goes from strength to strength, becoming Marie Antoinette’s official portraitist and gaining entrance to the elite Académie Royale at the same time as Adélaïde.

When at last Adélaïde earns her own royal appointment and receives a massive commission from a member of the royal family, the timing couldn’t be worse: it’s 1789, and with the fall of the Bastille her world is turned upside down by political chaos and revolution. With danger around every corner in her beloved Paris, she must find a way adjust to the new order, carving out a life and a career all over again—and stay alive in the process.

Release date: August 30, 2022

Publisher: She Writes Press

Print pages: 285

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Portraitist: A Novel of Adelaide Labille-Guiard

Susanne Dunlap

Paris, August 1774

Whenever sleep eluded her, Adélaïde would gaze out the window of the third-floor apartment she shared with her husband and think about colors. She’d stare hardly blinking for hours, noticing all the subtle variations of hue that, to a skilled eye, gave the sky as much movement and character as a living creature. Even as a child, she had understood that nothing was fixed, that light changed whatever it touched. Take the human face: Skin was not one color, but many, and never exactly the same from one moment to the next. She knew, for instance, that if Nicolas ever discovered what she was going to do that day, his face would take on one of the shades of thundercloud that had become more and more familiar to her as they drifted apart, and then she would be obliged to cajole him back to a placid pale pink.

He lay in the bed next to her, sprawled on his back, snoring open-mouthed and dripping saliva on his pillow. With a snort, he rolled away from her, and Adélaïde eased herself out from between the sheets, nudged her toes into her slippers, and stood.

“You’re up early,” Nicolas said, making her jump.

She pulled on her dressing gown as she walked into what served as kitchen and dining area. “I’ll wrap up some bread and cheese for you.”

Nicolas threw off the covers and shook himself from shoulders to toes before whisking his night shirt over his head and dressing for his job as secretary to the clergy. Adélaïde handed him the parcel of food as he strode by on his way out. He turned before leaving and stared at her. “You’ve stopped even making an effort to be attractive. You could at least put your hair up.” He let the door slam behind him and thumped down the stairs.

He’s right, Adélaïde thought. But she didn’t have time to worry about that now. As soon as she heard the heavy outer door of the building open and close, she hurried down to the courtyard, filled a basin of water from the fountain, and brought it up to the apartment so she could bathe. When she was finished, she put on her one good ensemble—the one she wore to church on Sundays with bodice and sleeves that had been trimmed with Mechlin lace in her father’s boutique. Her plan was to leave and come back without anyone noticing before Nicolas returned for dinner.

After waiting for two women who lived below her to finish their conversation in the stairwell, Adélaïde tiptoed out of the house and took a circuitous route to the Rue Neuve Saint-Merri and the Hôtel Jabach so no one might guess where she was going. She passed as swiftly as she could along the crowded thoroughfares with their boutiques and market stalls selling everything from leather goods to live chickens, picking her way around piles of dung and flattening herself against buildings as carriages clattered by. Such strange turns her life had taken, she thought. If she had waited—as her father begged her—until someone more worthy asked for her hand, she might have been the lady she’d just seen pressing a scented handkerchief to her nose as she flew past in a handsome calèche. But at the age of eighteen, her mother dead the year before and all seven of her siblings buried, Adélaïde had been desperate to get away from home, to leave the memories behind and start a new life. Enter the dashing Nicolas Guiard, who courted her passionately and made her feel wanted. Then, she couldn’t believe her good fortune. Now, she realized she’d made a terrible mistake.

It was only ten o’clock when she arrived at the iron gates that opened into the courtyard of the Hôtel Jabach. She stood for several seconds and stared, taking in everything, fixing the image of this moment in her memory. She, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, was about to enter the first exhibition where she would not just be a spectator but a bona-fide, participating artist. Two of her pictures hung in one of the galleries within, her entries in the annual salon of the Académie de Saint-Luc—not the Académie Royale, but nearly as prestigious. Her teachers—François-Élie Vincent and Maurice Quentin de la Tour—had put her up for membership years ago, before she married, and she would be one of only two women exhibiting that year. It was a bold step, a leap in fact, beyond the trite watercolor miniatures she sold in Monsieur Gallimard’s shop to make a little pocket money. Those were not art.

As she passed through the gates and crossed the courtyard to the entrance, sweat ran down her back under the layers of stays and bodice and petticoats, pooled at her waist, and trickled down her legs into the tops of her wool stockings. She took the printed catalogue the concierge handed her at the door and started fanning herself with it before she even opened it.

The murmur of polite commentary echoed around her. Smartly dressed men and women sauntered in twos and threes, facing the walls and pausing occasionally to admire what caught their eye, then turning to examine the portrait busts and figures that dotted the middle of the floor on pedestals at regular intervals. From her earliest childhood, Adélaïde had been to many exhibitions like this one, in rooms that had been stripped of some of their furnishings and given over to the contemplation of art. She wanted to savor it all and take her time to feast her eyes on everything, to give herself a chance to appreciate the honor of having her own work displayed alongside that of more established artists.

It was in the second of the main galleries that Adélaïde first noticed a small group comprising a slight, dapper man, an older woman who could still be called attractive, and two young ladies of startling beauty. One of them had a face of such exquisite proportions that Adélaïde wished she’d brought a sketch pad and a pencil so she could take her likeness then and there. The other one, although not quite as pretty, exuded sensuality and was clearly aware of the power she had over men in general and the gentleman in their party in particular. She cast her eyes down, her long lashes fluttering against cheeks rosy with what might have been embarrassment if they hadn’t been carefully painted with vermilion stain. That was when Adélaïde overheard the gentleman say, “No, I insist. Your allegories are perfection, Mademoiselle.”

Adélaïde froze. Her allegories? That lady had pictures hanging in the exhibition? The only other female member of the Saint-Luc she knew of was the elderly Mademoiselle Navarre, a pastellist and miniaturist who painted still lifes, not allegories. This lady, whoever she was, must have been elected very recently. No others were on the roster of exhibitors the last time Adélaïde had seen it. She held her breath, willing herself to blend into the crowd, standing sideways to the group and pretending to examine a rather voluptuous rendition of Leda and the Swan. Her ears tingled as she strained to hear the rest of the conversation despite the ebb and flow of casual comments as visitors moved through the gallery.

“Do you really think so?” the lady said.

“I believe the world will be forced to acknowledge that the young Mademoiselle Vigée has made her mark and is ready to take her place among the most talented portraitists in Paris today.”

Vigée. It was a familiar name. Adélaïde associated it with an artist but not a lady. Then she remembered. The pastellist and fan decorator Louis Vigée had belonged to the Saint-Luc. He had died some years before. Could this be his daughter? She must be very young.

The voices faded as the group moved on to another gallery. Adélaïde opened her catalogue, hands trembling. The artists were not listed alphabetically, so she had to scan the entire booklet before she finally found the name Vigée along with that of another unfamiliar lady artist, Mademoiselle Bocquet. More than eight works by Mademoiselle Vigée were listed, several of them oil paintings. And Mademoiselle Bocquet showed three large pictures and a number of smaller portraits and têtes d’études. The two women were at the end of the listing of regular members, immediately before the agréés, the apprentices, and must therefore have been a very recent addition—a guess that was confirmed by the fact that both of them had donated the most significant of their paintings to the academy. So, they were full members, not apprentices. She, Adélaïde, was still just an agréé.

Several of Mademoiselle Vigée’s sitters had titles—comte, duchesse, baronne. Adélaïde hadn’t had time to examine the artist’s clothing, but she had the impression of silk and lace, of an extravagantly trimmed hat—evidence of affluence. She herself could hardly afford gum Arabic for pastels and the most essential pigments and was forced to execute works on inexpensive paper. This young lady artist had the luxury of working in oils on the much-more-costly canvas.

Adélaïde’s stomach churned. Why, oh why had she waited six years to show her work in an exhibition like this one? How could she hope to compete with someone like Mademoiselle Vigée, who it seemed had the further advantage of entrée to lofty social circles? Adélaïde braced herself to examine the allegories Mademoiselle Vigée’s gentleman friend had praised so extravagantly. Perhaps they weren’t very skillful. Perhaps family and friends engaged Mademoiselle Vigée out of kindness to indulge a whim, and she would exhibit this year and then disappear to marriage and children.

Yet as soon as Adélaïde stood before the three oval canvases, she knew the man she had overheard had not spouted empty praise. Mademoiselle Vigée had a tendency to emphasize prettiness in the shape of a face, but the flesh tones and drapery—exquisite. Adélaïde had studied enough about oil painting to appreciate the subtle use of glazes to bring the model’s skin to life. Because she must have had models. No one could paint the musculature of a female back and arm so accurately by trying to look in a mirror or relying on imagination. And the attention to detail, the fine brush strokes, the composition—it all indicated a high degree of skill and the best training.

Models. Oils. Training. Hope drained from Adélaïde’s heart. How could her two modest offerings compare to these? A miniature watercolor and a pastel, with only herself as model in one and an engraving as the source of the other. Perhaps it was too late for her. She’d waited, hesitant, doubtful of her own worthiness. But why? Her teachers had pressed her again and again to display her work in public, but she resisted for reasons that had nothing to do with her desire or ability.

They had to do with Nicolas. At least, the idea of him, the thought that his regard for her diminished every time she picked up a brush or a crayon and that he disdained the one thing that mattered to her more than anything else. At first she’d tried to draw him into her ambitions, asking him to sit for her. He’d refused. He’d told her it was childish to pass her time in that way and that he was too busy earning her keep to indulge her. That was when she started hiding her work from him, pretending she’d given it up or at least given up any serious idea of becoming a painter. He had little regard for art anyway. The only pictures he truly appreciated were the erotic drawings he bought on occasion. He tried to hide them, but in their small apartment, nothing escaped her notice. When she discovered a sheaf of titillating engravings in a folio under their bed, she hadn’t been so much disgusted at the subject matter as at the crudeness of the execution.

What was so shameful about sexual pleasure anyway? Many of the pictures sanctified as art by the academies were blatantly erotic. Adélaïde took a long look at the dozens of portraits gazing down at her in attitudes of pride and coquetry and thinly veiled desire; the mythological subjects of rape and seduction; the fecund landscapes inviting her into distant vistas; the still lifes where exhausted flowers shed their petals in a constant state of incipient decay; the grand history paintings that froze men in attitudes of action and women in simpers of adoration or weakness. No, she thought. She would not be intimidated. She belonged here as much as anyone. She’d been told she had talent and knew she had a limitless capacity for hard work. This Mademoiselle Vigée and her friend—what did it matter if they were artists too? The world had an unlimited supply of paint and canvas and subjects. There was room for all.

Yet, in the back of her mind, Adélaïde suspected that there might be less room for women artists than men and that if Mademoiselle Vigée continued to paint, a day would come when they would be considered rivals. Right now, Mademoiselle Vigée had the clear advantage of training and resources. No matter. That situation could be remedied. Adélaïde would take steps to narrow that gulf, something she knew she would have to do sooner or later. So, it would be sooner. She had put off owning her place in the art world long enough in deference to Nicolas’s amour propre.He must learn to accept who she was. If he didn’t—well, she would cross that bridge when she had to.

Adélaïde took a few steps toward the gallery where she thought she’d find her own pictures, then changed her mind. She was too preoccupied, too unsettled, to view them dispassionately. So she left the Hôtel Jabach without looking for them and made her way back to the apartment, her mind galloping ahead. She’d return the next day, or possibly the day after, when she’d thought it all through and would be calm enough to face her pictures and judge them as a visitor might.

Adélaïde hadn’t had time to change out of her Sunday habillement before she heard Nicolas enter the building and pound up the stairs two at a time. Courage, she thought. She would tell him straightaway. Perhaps he would surprise her and be glad. Perhaps the prospect of lucrative portrait commissions that would result from the exhibition would soften him, and he wouldn’t accuse her of preferring painting to spending time with him or of being unwomanly for pursuing a career that would put her in the public eye. She smoothed down her hair that still bore traces of powder and took a seat at the table, raising her cup of tisane to her lips as Nicolas burst through the door.

“What is this!” His eyebrows were drawn together, and his eyes flashed as strode over to her and waved a booklet in her face.

“I-I don’t know.” There it was. The thundercloud—darker than she’d ever seen it. He didn’t even look like himself. And of course, she did know what it was. The exhibition catalogue. Her own copy remained tucked in the pocket tied around her waist beneath her petticoats.

He leaned down toward her. His eyes were red, as though he’d been crying. For an instant, shame washed over Adélaïde. She should have told him, been more honest. “I’m sorry, I should have …” She couldn’t think in that moment exactly what she should have done, knowing that he likely would have forbidden her to exhibit. Most husbands would have done so in the same circumstances. She’d been naïve to think otherwise.

Nicolas took two steps away and then wheeled around to face her again. “Do you know who gave this to me? Do you know? The miniatures you sold were bad enough. I had to laugh them off, claim they were nothing more than a harmless whim.”

So, he knew about the miniatures. “But, I told you when we married—”

“You tricked me! You and your father. All along you were just waiting to humiliate me.”

A harsh sob escaped his throat, and he gripped her upper arm and yanked her out of the chair, sending it tumbling backwards. Adélaïde felt his fingernails through her sleeve and bit her lip to keep from crying out, afraid to struggle against him.

“I should have annulled the marriage the very next day! You couldn’t give me children anyway. All you wanted me for was to support you so you could indulge your precious painting.” He kicked a nearby chair and sent it across the floor. “Who did you have to sleep with to get your pictures in this salon?!”

He threw her away from him. She lost her balance and fell. He began ripping pages out of the catalogue and crushing them in his hands.

“Nicolas! You forget yourself!” She tried to scream the words but they came out strangled and husky.

“I? I forget myself? You’re my wife! You’re supposed to love and obey me! Instead you make me a mockery!”

Before she could scramble away, he grabbed her again and raised his fist. It was the last thing Adélaïde saw before the world went black.

At first, when Adélaïde awoke later, her eyes wouldn’t focus. She blinked hard, and gradually her surroundings began to take shape. But everything was in the wrong place. She wasn’t in her bed. She lay on something hard and was surrounded by broken china and smashed bits of wood. The floor, she thought. She pushed herself up on one elbow. “Arghh!” The pain in her arm was so intense she couldn’t suppress her cry and fell back down. Don’t push yourself up, she thought, and clenched her stomach muscles to raise herself to a sitting position. Her head pounded as if it were about to explode with pain on one side of it. She bit her lip to keep from crying out again and surveyed the scene around her.

It was the apartment. But it looked as if some whirlwind had come through and hurled every item she owned around the room, smashing it to bits. Even the bedding was torn in shreds. She lifted her right hand to the sore on her head and touched something sticky. She smelled her fingers. Blood. Then she looked down at her left hand and swollen wrist. When she tried to move it, pain shot all the way up her arm. Where was Nicolas? There was something …

Bit by bit, she remembered. She’d been in the apartment, just returned from the exhibition. Footsteps pounded up the stairs from the street. The door flew open. Nicolas, his face purple with anger.

And she had hoped he wouldn’t mind. How foolish.

She was still wearing her good dress, but it was torn and dirty. Her head had cleared, although pain pulsed in one spot. Adélaïde rolled onto her knees and pushed herself up with her right hand. Her right hand. Thank heavens. He hadn’t injured her painting hand. She went to the small mirror in the bedroom and examined the nasty bruise that half closed her right eye. She took a scrap of linen and soaked it in water, wincing as she patted the bruise and cleaned up the blood on her head as best she could.

She and Nicolas might have become distant and prone to arguing over every little thing, but this—to injure her. She would never have foreseen it. She didn’t know him at all, it seemed. Now the apartment that had been her home for six years felt perilous, like a foreign landscape with monsters hidden in the corners. There might as well be. It contained so little of her. She’d erased herself from her home gradually over the years, as she drew herself in, folding her wings for protection. She thought it had been only to protect her soul, her heart. Now, it seemed she would have to protect her body as well.

Whatever was to happen in the end, she needed to be away from Nicolas now. But how? If she left to find a room somewhere, the police would simply return her to her husband with an admonishment that she should behave better and maybe he wouldn’t hit her. The only option was her father. But would he take her in? Their relations had become strained ever since she married against his wishes. He would no doubt congratulate himself at how right he’d been about Nicolas. But it didn’t matter now. He was all she had. She’d never cultivated female friends, always too busy with her art in every spare moment, and whatever other distant relations she had lived far away in the provinces.

Adélaïde found a shawl and wrapped it over her head and around her shoulders, although it was hardly the season for it. With great care, discovering new sore spots and aching muscles with every step, she gathered all her hidden art supplies and packed them into a satchel. She paused in the open doorway and took one more look around the apartment she and Nicolas had entered so joyfully six years ago, then walked out of the building, never to return.

That evening, after her father’s companion Jacqueline had cleaned the gash on her head, put a cool cloth over her eye, and wrapped her wrist, Adélaïde sat sipping wine at the kitchen table in the capacious apartment.

“You have every right to feel triumphant,” she said to her father. “But as I said, Nicolas has never behaved this way before. You didn’t really know him. He could be very kind.” Even as she uttered the words Adélaïde knew she was stretching the truth, although she wasn’t certain why she would bother to do such a thing.

Claude-Edmé Labille reached out and patted his daughter’s good hand. “Why would I feel triumphant that my only surviving child has been hurt? Do you really think me so heartless? And the fact that he hasn’t beaten you before changes nothing. Now you know he is capable of it.”

Adélaïde gazed at her father in his scarlet silk dressing gown, still looking well-dressed enough to serve one of his wealthy customers although the shop was closed for the evening. It had been months since she’d visited him. The last time, she had pretended everything was well with Nicolas. Her visit hadn’t been long enough to discover that Jacqueline, whom she knew only as the head seamstress in the workshop, had become much more than that to her father.

After Jacqueline discreetly retired to another room, Adélaïde said, “So, Jacqueline—” and smiled.

A delicate pink—no more than a drop of carmine mixed with lead white—suffused her father’s cheeks. “None of that now,” he said. “We must speak of you and your predicament. What will you do?”

Adélaïde’s mind whirled, thoughts chasing each other too fast to be spoken. After a time, though, she managed to catch two threads that circled back and back, demanding her attention. She had a simple choice: She could return, Nicolas would apologize, and she would go back to hiding her ambition and try to be careful not to put him in that position again or to provoke him in any way that would goad him into violence toward her. That would be the easy thing to do. It would be what most would expect of her, a married woman.

But perhaps his actions had given her an excuse to make the other choice. The difficult choice. She stood on a threshold between her past and her future. To go one way would be to go backwards. But to go forward—was she brave enough? Brave enough to take charge of her own life, whatever that meant? The thought sent a shudder through her. She looked up into her father’s eyes. Smile lines stretched from their corners and disappeared somewhere under his silk cap. He kept his gaze steady, giving her time to answer.

And then she knew. “I will not go back to him, to that apartment. We have to separate.”

The words echoed in a silence filled only by the tick of the mantel clock, drilling into Adélaïde’s aching head saying tsk, tsk, tsk over and over. More fool she was for ever expecting to be married and continue painting in the first place. Her father had warned her, but she wouldn’t listen. Marrying Nicolas had turned out to be more of an ending than a beginning. It had ended her lessons in watercolor with François-Élie Vincent and pastels with Maurice Quentin de La Tour. It had ended her Sunday strolls in the Tuileries or the Palais Royale gardens with her father. Nicolas demanded she promenade with him on Sundays and complained about any expense of which he did not approve. That was why Adélaïde started selling miniatures in Monsieur Gallimard’s shop—so she could make some money to purchase her art supplies. But that was all over now. “I cannot go back.”

Claude-Edmé spoke at last. “You are welcome to remain here as long as necessary. You must know that.”

Did she know that? Not many fathers would take in a disobedient daughter without scolding, without insisting that the law said she must return to her husband come what may, that Nicolas had been within his rights to beat her, that she had made the decision to marry him and must face the consequences. Her eyes burning with unshed tears, Adélaïde said, “I don’t deserve your kindness. If I stay it would be at most a temporary arrangement. For one thing, I need a studio.”

“If you stay? My dear, where else would you go? And this dream of yours, to be a portraitist. Are you certain that is what you want?”

Adélaïde hadn’t told her father about the salon. He was not a connoisseur of art, and he’d never complimented the few of her pictures he’d seen. His was the world of fashion, of rapidly changing styles that dominated society for a month or two and then vanished. How could he be expected to understand her desire to create something of beauty that also endured? She searched in his eyes for an answer. All she saw there was affection, tinged with sadness. It was enough. She reached out and took her father’s hand. “Yes. More certain than I’ve ever been of anything.”

“I confess, you aren’t like any other lady I know. The ones I serve in my boutique care only about what the queen wore to the opera or to the last ball. But you—” He smiled as he waved a hand at her now-disheveled gown and disarranged hair.

Adélaïde looked down at her dirty bodice and put her hand to her head. The absurdity of it all struck her, and she laughed, letting the tension of the past few days—of the past six years—spill out in gales of uncontrolled mirth. It hurt her sides and scraped her throat, and helpless tears rolled down her face and plopped onto the linen of her fichu before being absorbed as if they’d never fallen.

Adélaïde’s father stood and went to a cupboard in the corner of the kitchen next to the stove, which at this time of year was only lit when the daily serving girl was cooking. He bent down and opened the bottom drawer, withdrew a small metal box, and brought it to the table. Adélaïde stopped laughing, her breath coming in hiccups, and watched him as he pulled a tiny key on a silver chain out of his pocket, fitted it into the lock on the box, and opened it with a click. She was still too stunned, too thrown off balance, to wonder much what he was doing.

He pulled out a velvet pouch that clearly showed the outline of coins. “Here,” he said, taking her hand and placing the pouch in it. “I wish I could do more, but I have had to invest in some very costly lace recently.”

Adélaïde looked down at the pouch. All at once, she realized what he’d given her, and what it meant. She teased open the cords that held it closed and upended its contents on the table. One, two, three … The gold coins tumbled heavily onto the polished wood. Ten Louis d’Or. She gasped. It was enough to secure her own apartment and purchase many art supplies. “It’s too much!”

“Nonsense,” her father said. “What else should I spend it on? If you’d married differently, it would have been part of your dowry.”

“This is freedom,” she said. “Thank you.”

“Freedom for the moment. But as you appear to be certain you will not go back to your husband, we must get you a legal separation. And until then, you are not safe. You had best remain here for the time being. We must ensure that Guiard has no right to your assets or to your companionship. I will send word to my avocat in the morning.”

Just like that. Her father wanted to end the marriage as much as she did. Until that moment, Adélaïde hadn’t fully understood the depth of her father’s animosity toward the handsome, self-absorbed Nicolas. She supposed that if a child of hers had come to her beaten by someone who should have loved her, she would have felt exactly the same.

Adélaïde stood and walked around the table to stand next to her father, put her hand on his shoulder, and bent down to kiss his cheek.

He patted her hand and smiled. “You must be very tired. Jacqueline has made up your bed by now.”

Adélaïde took a candle and made her way to the bedroom that had been hers as a child, with its narrow cot, small cupboard, and nightstand. A clean shift had been laid out for her and a basin of fresh water waited on the stand. She splashed her face, unpinned and untied all her clothes and donned the shift, then slid beneath the light covers. She’d thought she’d never come back to that room, but here she was. No, I won’t cry. This wasn’t the end, it was a beginning. From now on, she would make sure that no one could deflect her from her purpose. She had wasted enough of her life being distracted by a beguiling, selfish man. From now on, if she wanted to make up for her six fruitless years chasing a kind of happiness she didn’t really want, she would have to keep to a steady path, her eyes focused ahead on her goal. A life as a portraitist awaited her. Now all she had to do was reach for it.

Adélaïde wrote to the Académie de Saint-Luc to tell them to send any communications to her care of her father at À la Toilette, his boutique. The last thing she wanted was for Nicolas—who she assumed remained in their apartment—to intercept any potential communications about portrait commissions. That, after all, had been one of her reasons for taking the chance and exhibiting in the salon—and the one she thought her parsimonious husband might actually appreciate. Now, he would certainly see them as what they were: her ticket to freedom. Without such commissions, she would never move past creating pretty miniatures to sell in a shop and never have enough money to survive on her own now that she was pursuing a separation. She ultimately agreed with her father that it would be best to wait until the separation was legally binding before getting her own apartment and studio because until that time, Nicolas would be within his rights to drag her back home or rape and beat her. Adélaïde didn’t really think he’d do that. But how did she know? The man who had attacked her two days ago bore little resemblance to the man she had fallen in love with.

She had little time to fret over such things if she was going to start moving forward. She would at last be able to get to work without any interference. There was the matter of completing enough pictures to be advanced from her position as agréé at the Saint-Luc, something that never would have been possible while she lived with Nicolas. She still had the catalogue and had looked again and again at the entries for Mesdemoiselles Vigée and Bocquet, experiencing anew every time a flood of piercing envy as she read of their portraits in oil of aristocrats and nobles, imagining they had studios stocked with all the materials they needed and had room for sitters too.

Adélaïde returned to the Hôtel Jabach as soon as she could wear a hat without pain and the swelling around her eye had gone down. She needed to see her own pictures there, to see if they belonged among the others, truly, or if she’d been deluding herself that she was good enough to take her place among professionals. She walked through the galleries slowly and examined every single oil painting, pastel, watercolor, drawing, and sculpture, making notes in the catalogue about each one. She did not hurry to see hers. She wanted her eyes to be full of everything around them first, to be saturated with all that a dispassionate observer would see.

And then she turned a corner, and there they were. Her shoulders unclenched. She allowed herself to smile and looked around to see if anyone else was near. A couple had just entered the chamber and walked over to her two entries, stopping in front of them. Adélaïde pretended to be examining a portrait bust on a plinth in the middle of the floor, her ears tingling to hear what, if anything, they would say.

“He’s so alive!” the woman whispered. The man mumbled his agreement. And then they passed along and out of the gallery.

Adélaïde supposed it was enough. Her portrait of the magistrate did give him life and presence—La Tour had counted her among his best students. And now she could honestly see that her work was just as good as the others in the salon. Better than some.

She passed swiftly to Mademoiselle Vigée’s allegories to look at them again with her own pictures in her mind. Her first impression was confirmed. This was the work of a formidable rival. As to Mademoiselle Bocquet—she did not possess quite as much talent and ability as Mademoiselle Vigée or Adélaïde herself, but she, too, had been admitted as a full member. Why? What influence did they have?

On her way out, Adélaïde stopped to talk to the guard on the pretext that she might be interested in commissioning a portrait from Mademoiselle Vigée but that she couldn’t decide between her and Mademoiselle Bocquet. “She was elected as a member to the Saint Luc recently, wasn’t she?” Adélaïde said to the old man who’d been dozing on a chair by the main door.

“Ah yes.” He leaned forward and lowered his voice. “It was quite unexpected. Bit of a scandal, really. You know officers from the Court of the Châtelet raided her studio in July. They confiscated everything she had.”

“How distressing!” Adélaïde said, caught between genuine outrage and secret glee. “What for?”

He leaned yet closer. Adélaïde could smell his pungent breath and had to will herself not to back away. “They said she’d been painting professionally without a license from the Guild.”

“Hah!” Adélaïde said, taking a step back. “And how would she have gotten such a thing? Women can’t belong to a guild.”

The guard shrugged. “Beh. She had everything back in a few weeks anyway. And as you see, she’s well connected. Her godfather Gabriel Doyen got the officers of the Saint-Luc to vote her and her friend in with a special session. It doesn’t hurt to be so nice to look at either.”

Adélaïde wanted to ask if a man’s looks were taken into consideration when being elected to the Académie de Saint-Luc but thought better of it.

The guard prattled on, furnishing all the information Adélaïde could possibly want. The older woman she had seen with them at the opening was apparently Mademoiselle Vigée’s mother, who as a widow had married a jeweler named Jacques Le Sèvre. And yes, Mademoiselle was indeed the daughter of Louis Vigée. As to Mademoiselle Bocquet, her mother taught drawing to ladies and was quite well known. Her father owned a bric-a-brac shop not unlike that of Monsieur Gallimard.

Adélaïde jotted this information in her catalogue before pressing a coin into the guard’s hand and taking her leave.

While she had been indoors, a brief rainstorm had washed the Paris air clean and left behind puddles that carriages splashed through to the consternation of pedestrians. Adélaïde took deep gulps of air as she walked, choosing a route off the busiest roads that would enable her to pass through the gardens of the Palais Royale. Her heart was full of art and ambition, and, passing by the palace that held one of the finest collections of paintings in France and therefore probably the world, it somehow seemed a fitting way to end her momentous day.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...